By Bradley Graham

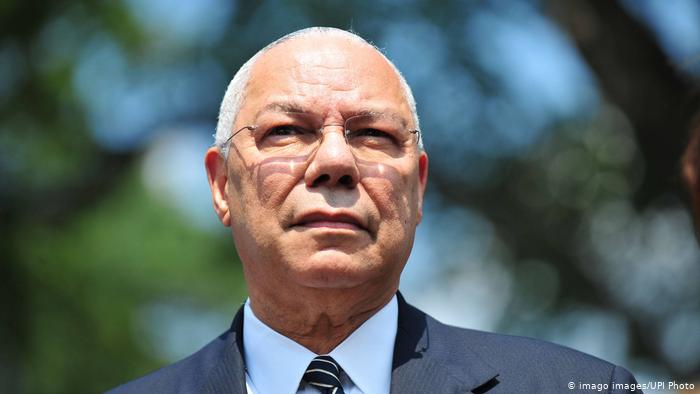

Colin L. Powell, who helped guide the U.S. military to victory in the 1991 Persian Gulf War as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, then struggled a decade later over the U.S. invasion of Iraq as a beleaguered secretary of state under President George W. Bush, died Oct. 18 at 84.

The cause was complications from covid-19, his family said in a statement. He had been treated at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., his family added, noting he had been fully vaccinated.

Born in New York to Jamaican immigrants, Gen. Powell rose rapidly through the Army to become the youngest and first Black chairman of the Joint Chiefs. His climb was helped by a string of jobs as military assistant to high-level government officials and a stint as national security adviser to President Ronald Reagan. Charming, eloquent and skilled at managing, he had a knack for exuding authority while also putting others at ease.

As the Pentagon’s top officer, he played a prominent role in restoring a sense of pride to the nation’s post-Vietnam military and began the reshaping of American forces after the end of the Cold War. His famous prescription for the use of force, dubbed by journalists the Powell Doctrine, called for applying military might only with overwhelming and decisive troop strength, a clear objective and popular support.

His selection by President George W. Bush in late 2000 to be secretary of state transformed Gen. Powell from soldier to statesman and made him the first Black person to lead the State Department. But his four years as secretary proved his most difficult assignment.

A pragmatist and a strong believer in international alliances, Gen. Powell often found himself the odd man out in an administration dominated by neoconservative ideologues who were dubious about the usefulness of the United Nations and NATO and all too ready to employ U.S. military power.

Other than his well-known reservations about military intervention, Gen. Powell, as he often acknowledged, was not given to grand principles. He saw himself primarily as a problem-solver and expert manager.

Gen. Powell harbored deep misgivings about the timing of the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the size of the invading U.S. force. But he ultimately supported the action, lending his considerable credibility to making the public case for war. It was a move he later regretted.

While hailed on his retirement from public service at the end of Bush’s first term as a figure of honor and distinction, Gen. Powell was also criticized for not pushing harder to block the Iraq War or quitting in protest.

In his defense, Gen. Powell cited a sense of duty and obedience to presidential authority. “It’s just like in the military — you argue, you debate something, but once the president has made a decision, that becomes a decision for the Cabinet,” he said on CNN’s “Larry King Live” in July 2009.

Bush had brought Gen. Powell into the Cabinet to lend immediate credibility and gravitas. But Gen. Powell’s power and influence were frequently undercut by more hard-line colleagues, notably Vice President Richard B. Cheney and Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld, who viewed him at times as too solicitous of foreign interests and insufficiently supportive of Bush’s vision for the muscular exercise of American power.

Gen. Powell was able to claim some victories early on. In his first year as secretary, he won the release from China of the crew of a U.S. surveillance plane that had made an emergency landing after colliding with a Chinese plane over the South China Sea, killing a Chinese pilot. He averted the pullout of U.S. troops from NATO peacekeepingoperations in the Balkans, and he facilitated the U.S. withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty without provoking a harsh Russian backlash.

In other key foreign policy areas — among them, diplomacy with North Korea and efforts to ease Arab-Israeli tensions — Gen. Powell made little headway even inside the administration. Increasingly, he saw his mission as mainly moderating the more extreme tendencies of Bush’s team and avoiding disaster.

“Serving as a brake on rash presidential actions and misguided policies was not the forward-looking role Powell had envisioned for himself as the nation’s chief diplomat,” Washington Post journalist Karen DeYoung wrote in “Soldier,” her 2006 biography of Gen. Powell.

In the weeks after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, when the idea of attacking Iraq first arose, Gen. Powell helped persuade Bush to stay focused on striking al-Qaeda camps in Afghanistan.

Throughout 2002, Gen. Powell continued trying to slow the march to war with Iraq, warning Bush in a meeting in August that an invasion could destabilize the Middle East and shackle the United States with a great reconstruction burden.

“You break it, you own it,” he recalled saying.

But Gen. Powell eventually threw his substantial public credibility behind the decision to attack Iraq, agreeing to Bush’s request to present the U.S. case for war to the U.N. Security Council in February 2003.

His 75-minute speech, asserting that Iraq possessed chemical, biological and perhaps even nuclear weapons, proved deeply embarrassing when no weapons were found after the invasion. He told an interviewer several years later that the speech would remain a “blot” on his career, which was “painful” for him to accept.

For the entire article go to:www.washingtonpost.com