In her third book, Hill hopes women see they are not alone in this battle.

By Gary Lee, The Oklahoma Eagle

Anita Hill has changed.

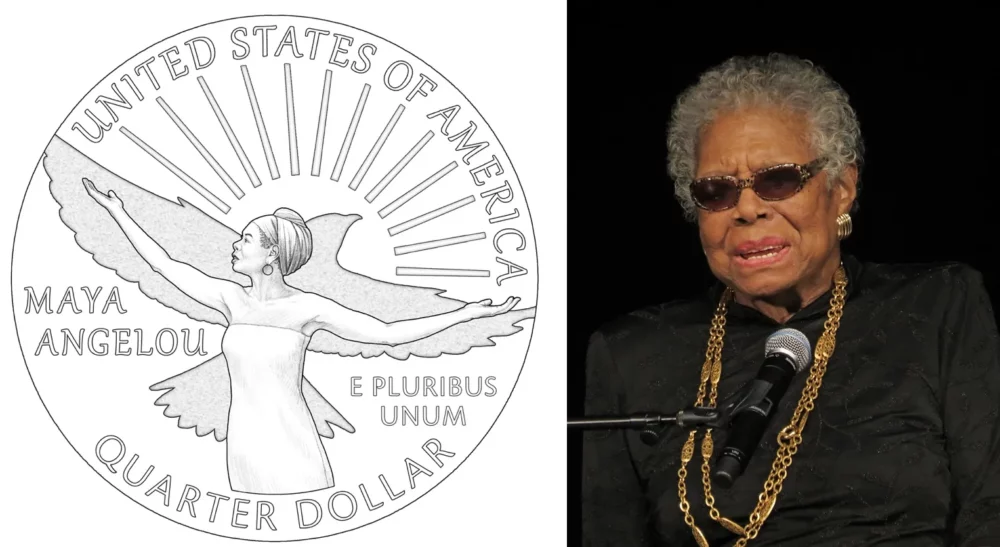

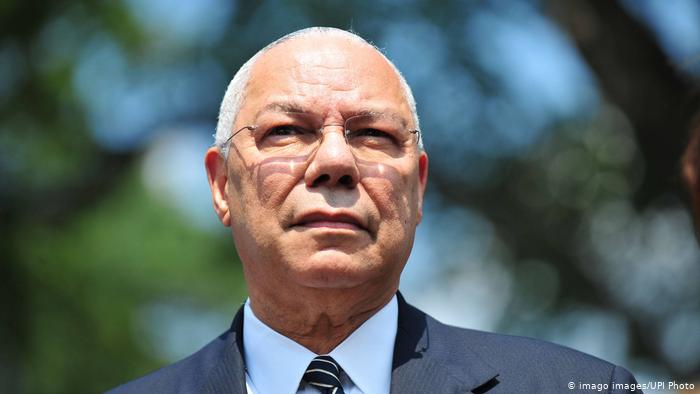

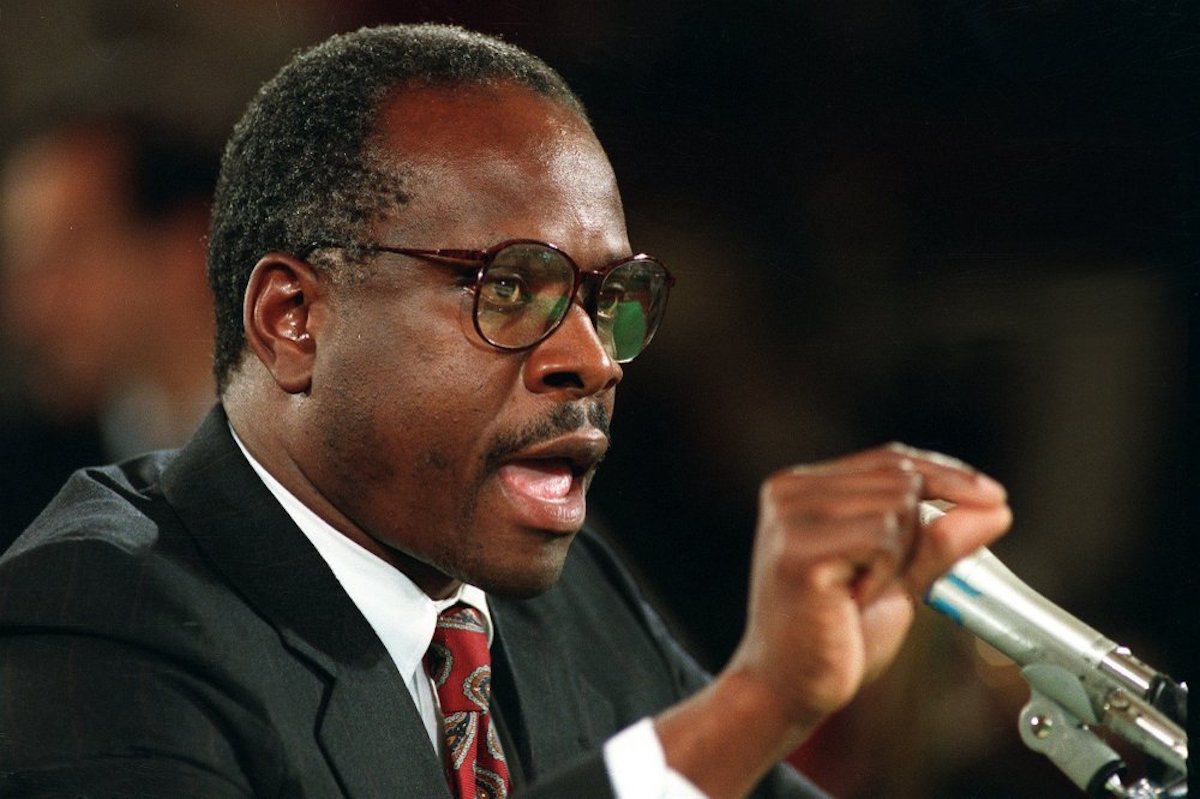

To be sure, the calm, powerful voice of advocacy for gender equality is still there. Thirty years after her riveting testimony in the 1991 U.S. Senate confirmation hearings of then-Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas, she sounds the clarion call against sexual harassment as clearly as ever.

In her new book, “Believing: Our Thirty-Year Journey To End Gender Violence,” she documents in detail the zig-zag path the country has taken towards gender equality since she first inspired a national dialogue on the topic.

At 65, Hill also continues to hold her Oklahoma roots close. Born and raised as the youngest of thirteen children on a farm of cotton, peanuts, and soy in the central Oklahoma town of Lone Tree, Hill graduated from Morris High School, gained a degree in psychology at Oklahoma State University and a law degree at Yale University. She then taught law at Oral Roberts University and Oklahoma State University.

But her years as a professor at Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts,

and a career as a national lecturer with rock star status have not diminished her down-home mannerisms. While the new book delves deep into contemporary national gender dilemmas, it is laced with lessons Hill learned on the rural family farm from her parents, Albert and Erma Hill, and her older siblings. Seven of them live in the Tulsa area (including this writer’s mother, Elreatha Lee, her oldest sister), and she visits regularly.

In an interview this week with The Oklahoma Eagle – held between her appearances on MSNBC, a forum with former United Nations ambassador and Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young, and a discussion with Ford Foundation President Darren Walker – she was approachable, conversational, and warm.

What was different was Hill’s exasperation. In contrast to the calmness of her early years, her tone and message were infused with urgency.

“My patience is waning,” she said. “I want people to understand that if you live in this country, you have a stake in the issue of gender equality. And you must do something about it. The time to act on that obligation is now.”

A sharply focused mission

Time has sharpened Hill’s professional mission. Following school, she initially launched into a career as a professor at the University of Oklahoma College of Law, specializing in commercial law and contracts

But the 1991 Senate Hearings testimony inspired her to reconsider her calling. Other prominent leaders told her that the country badly needed a Black woman’s voice on gender issues. A fast-paced life came on quickly, as she balanced roles as a university professor, public speaker, and national folk hero.

“Believing,” Hill’s third book, seals her position as a leading authority on gender equality and a driver in the national and international gender equality movement. She uses it to chronicle the key events in the years-long battle for equality and the resistance to it. In every chapter she recounts historic legal cases, wrangling over statutes, behavior shifts, and public debates the nation has gone through on the road to promote equality.

This is a book that students of American culture can read to find out what gender equality is about and why it’s important. It details the milestone events – the birth and evolution of the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements, landmark decision in the courts, the uproar over former President Donald Trump’s Grab ‘um by the pussy statements and more.

In one moving section, Hill recounts in her reactions to Christine Blasey Ford’s charges during Brett Kavanaugh’s hearings for his nomination to the Supreme Court of how he had assaulted her as an adolescent. (In the last episode of the podcast “Because of Anita,” Hill and Blasey Ford compare their experiences testifying against Supreme Court nominees.)

“I feel as if I have been writing this book for thirty years,” she told the Eagle. “I wanted to take stock of everything that has happened in gender equality – the memoires, the books – the reckonings. I wanted to put it together and say, here’s where we have to start to work together to change things.”

Victims of sexual harassment and gender violence may also turn to the book to see that they are not alone. Hundreds of victims and survivors have called or written to Hill to share their heartbreaking sagas. Hill, in turn, mentions many of the stories in the book.

Hill’s close accounting of the steps forward and backward in the campaign for gender equality leaves a reader of “Believing” with a sense that since her 1991 Senate testimony, the fight has had only incremental successes.

And, indeed, in the interview Hill said that there has been forward movement in some areas and failures in others. The statistics and reports show that over the years, incidents of sexual harassment and aggression across the U.S. have not diminished much, she said. “In terms of behavior, we have a long way to go as a country,” she told the Eagle.

Advances in cultural awareness

In terms of processes and systems, change has also been minimal, Hill feels. American society continues to find and favor ways to diminish the reports of victims of violence, she said.

In contrast, there has been a marked improvement in public awareness of gender inequality and sexual harassment. The willingness of victims to come forward has helped bring about a national understanding of how massive the problems of sexual harassment and gender equality are. “The cultural awareness of gender issues is where there has probably been the most significant change,” she said.

Hill uses the book to draw attention to the often-overlooked topic of gender-based violence affecting women of color, particularly Black and Native women.

She recounts several harrowing cases of in point.

One particularly haunting story was about Beverly Guy-Shethall, a professor at Spelman College who broke off a relationship with a colleague. He proceeded to harass, threaten and stalk her. He even wrote her name and telephone number in men’s toilets across Atlanta. Eventually, he was prosecuted and fired.

More often, she said, fears keep Black women from reporting such cases.

“What is missing in the discussion is our ability to come to terms with the dual impact of racism and sexism,” Hill told the Eagle. “There will be no complete elimination of gender-based violence until racism in its many forms is addressed. The reverse is also true. That does not mean that we have to choose one fight over the other.”

“Believing” also sheds light on gender-based violence among working classes. While much of the national discussion has centered on harassment and violence issues in Hollywood, corporate offices or white-collar workplaces, the problem is equally rampant among service workers in restaurants such as McDonald’s and in other lower-wage workplaces. The fears among victims of losing their jobs make the issues in this sector even more difficult to address, Hill said.

The book also points out that men, too, are often overlooked victims of sexual violence. Following her 1991 testimony, many men wrote to her with stories of how they had been bullied and victimized, she said. But she found that few come forward publicly because when they do, they are often teased and stigmatized. Hill said part of the solution involves creating safe spaces for men to discuss what is happening to them.

How to be part of the change

In “Believing,” Hill encourages society to be more active in giving solutions to gender violence. Above all, she says, “we need to collectively hear and see victims and survivors as central to any solutions we offer.” It’s essential to stop normalizing perpetrators’ aggressive acts and behavior by dismissing it as “not so bad.”

People in communities like Tulsa can be part of the solution, too, Hill told the Eagle.

On a personal level, she said, they can start by engaging in educational institutions of all kinds, pointing out that the bullying behavior of students is unacceptable. Parents, grandparents – everyone should enter this discussion, she added. “Whether your kid is bullied or being bullied or not, everyone in the school is affected by the behavior.”

People can also pressure their political representatives to take stronger public stances against gender violence, she said.

Finally, people should examine their behavior. They can start by asking themselves questions: how aware we are of the gender-based violence we witness in everyday life; how active are we in standing up against it?

“We are now in a period of reckoning about gender-based violence,” she said. “We should not let this moment pass.”

WHERE TO BUY BOOK

Tulsa readers can find Anita Hill’s “Believing: Our Thirty-Year Journey To End Gender Violence,” at Magic City Books (210 E. Archer, Tulsa, 918-602-4452) or Fulton Street Books and Coffee (210 W. Latimer St. 918-932-8646)