By Hannah Zozobrado, University of Maryland, The Oklahoma Eagle Student Journalism Project

Just over 100 years ago, African American Dick Rowland, 17, had entered an elevator where Sarah Page, a White woman, would later claim Rowland assaulted her. Like walking straight into a trap, Rowland had walked into the elevator as an innocent teenager and walked out as a victim of false accusations.

As Rowland’s later-arrest stirred controversy and, in turn, heightened the violent tension between the white and Black communities, the false accusation had ultimately acted as a catalyst for the critical event in Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District’s racial history: the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

Today, the city still works to remember the bloody massacre. During the centennial last year, Tulsan artists and creatives prepared and showcased their works in commemoration in the Historic Greenwood District, now designated a National Historic Place.

Among those many artists and creatives were music producer Stephon “Steph” Simon, 34, and poet Phetote Mshairi, 50.

Simon and Mshairi, both being born and raised in Tulsa, have found that their respective crafts intersect with local history. Like testaments of the social atmosphere within the city, poetry and music have served as outlets to commemorate a past that has shaped Tulsa into what it is today.

The influence of ‘Sugarhill’

While he is a poet, Mshairi’s first exploration of the art of word wasn’t poetry – it was rap.

It had been on a summer-like day in his youth, as he came back into the three-bedroom house after playing outside with friends, when he saw his four siblings gathered around a record, listening to The Sugarhill Gang and writing up rap lyrics.

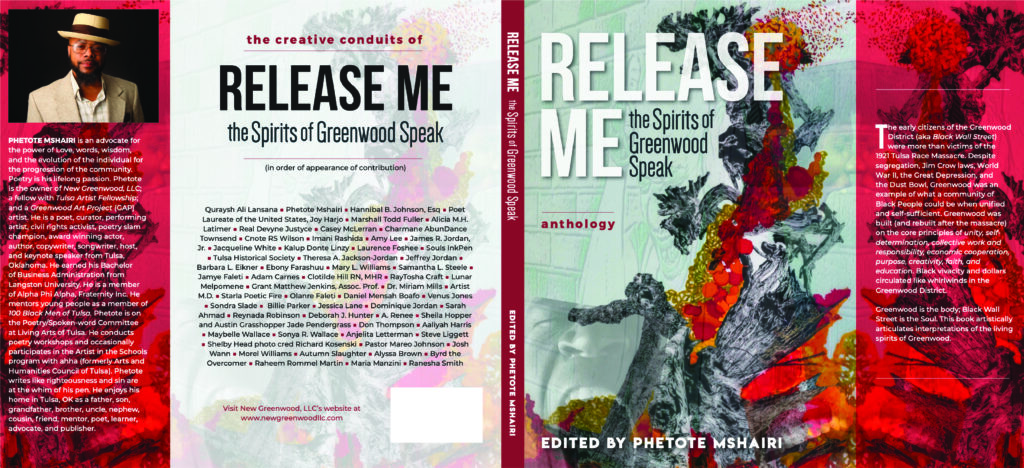

Mshairi, a bold, confident child at his young age, was willing to give raps a shot. He began to write lyrics and, as his passion gradually built on itself over time, he eventually gravitated from writing lyrics towards poetry by the time he attended Langston University, the only historically black college or university in Oklahoma.

“The transition was pretty easy, I just really focused on poetry when I got to college,” Mshairi said. “I always liked words and realized and appreciated the power of words. So, to try to make a transition from writing raps to writing poetry… it’s really two sides of the same coin.”

College had been where Mshairi got to further explore the art of poetry, but it was also where he had the opportunity to do so through the lens of history.

“I started to turn my writing into poetry… and at the time, I wrote about the subjects of mainly history,” Mshairi said. “When it was time to present and do speeches, or present in front of the class, I chose to do it in lyric form. I chose to do it in poetry form. It was just more comfortable for me to do it that way, and I thought it was creative.”

The first time Mshairi heard about the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre in a formal, classroom setting was in college; the first time that he ever heard about the massacre was at home when his mother spoke with Eddie Faye Gates, the late educator-turned historian and author who sought to preserve the stories of massacre survivors both in video and audio recordings.

“I heard about the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre over a conversation that my mother was having with Eddie Faye Gates,” Mshairi said. “I didn’t hear it in high school. I didn’t hear it in elementary. I heard it in college when I went to Langston University. That’s the first time I heard it in a school setting. Not to say that it wasn’t taught anywhere else… just not in my schools.”

A community spirit, united cause

Mshairi, thriving today as a poet, songwriter and entrepreneur, is heavily involved in Tulsa’s poetry and arts scene. As someone who is also a recipient of the Tulsa Artist Fellowship – which is an initiative that works to bring together Tulsa artists and facilitate cultural conversation – Mshairi has found a sense of community amongst the other fellows.

“The fellowship gives me an opportunity to be around other great artists… It’s hard to say, ‘I want to be an artist for a living.’ And it’s hard for anyone outside of that to understand it,” he said. “Whereas, I can be around other artists, and they say, ‘I get it.’ We inspire each other, encourage each other, motivate each other, push each other.”

According to Mshairi, the music, arts and poetry community has grown over the years. He believes it to be because people from all walks of life have felt more welcomed and comfortable, but also because “people want to be heard,” especially with the coronavirus pandemic.

“Writers tend to write from passion and from reality, and a lot of fodder, a lot of material came from the pandemic,” Mshairi said. “It forced us to be innovative and to create using media mediums, having Zoom concerts and online concerts.”

Poetry and songwriting

The community moved to an online setting and still managed to keep the energy alive. And while music and poetry are distinctly different art forms, Mshairi believes that the two intersect, more often than not, to create a holistic sense of community between local artists.

“For me they’re the same,” he said. “I think the songwriter is… a poet. I think it’s well-known that it’s interlaced… The poet writes ‘I love you’ in a way that the average person may not know how to express it. So, they get it in a greeting card. They get it in a song.”

Simon: ‘Fire In Little Africa’

A twenty-year-old Simon sat in his apartment and watched YouTube videos of American Hip-Hop group G-Unit. In one of his videos, Jayceon “Game” Taylor – a member of G-Unit, at the time – announced that he would be starting up a new label: Black Wall Street Records.

This was the first time Simon ever heard of the phrase “Black Wall Street.”

“Game [was] one of my favorite rappers at this time… and he was screaming ‘Black Wall Street’ on all of these songs that I was listening to on YouTube,” Simon said. “On the related search bar on the right side… there was a Tulsa Race Massacre, Black Wall Street documentary. I watched the documentary, probably 30 minutes long, and that’s when I found out.”

Though born and raised in Tulsa, Simon, 34, hadn’t learned of the city’s history before accidentally stumbling across the information on YouTube. This knowledge proved to be integral in his current work involving advocacy; from watching G-Unit and 50 Cent on YouTube in his apartment, Simon is now an executive producer and artist for Fire In Little Africa, a “multimedia album commemorating Black Wall Street” that released on May 28, 2021, just around the centennial of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

“It’s more so shedding more light on the good parts of Greenwood and Black Wall Street and the history that we had, to emphasize who we were and what we’re trying to get back to being,” Simon said. “We made a collaborative effort with over 100 artists… and narrowed it down to five weeks of recording the 21-track album that landed on Motown.”

‘Dicky Ro’

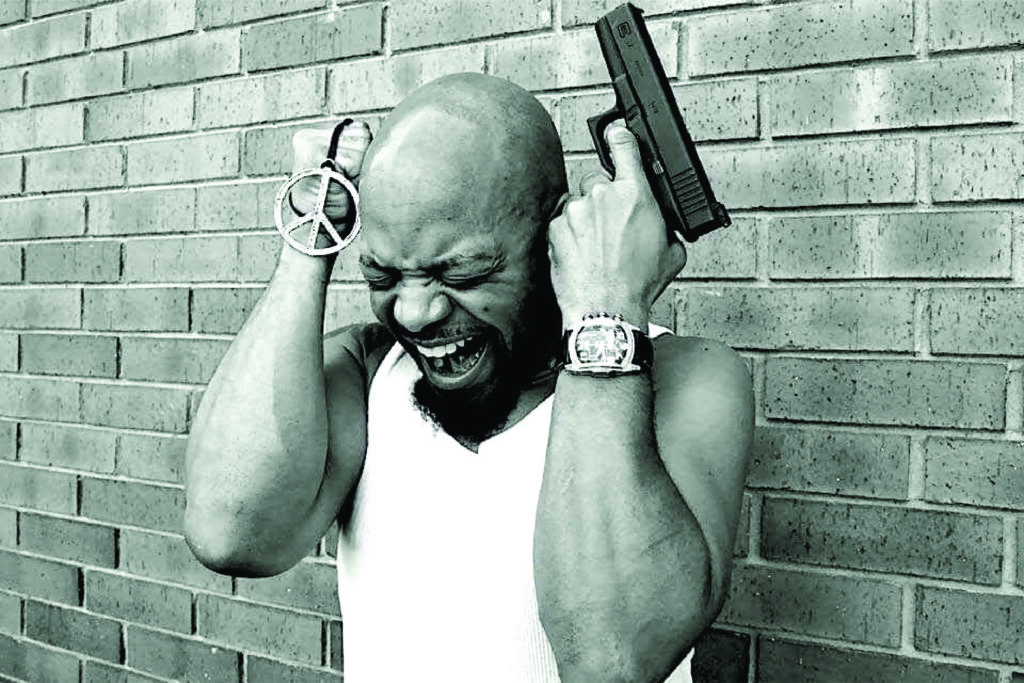

According to Simon and based on his own experience in the Tulsa education system, the history is not widely taught in Tulsa area schools. For Simon, the discovery of Black Wall Street and the massacre has since largely impacted his work – as a current musician, Simon often refers to himself as “Dicky Ro,” short for Dick Rowland.

“It’s more so of a reinvention of stirring the pot,” he said. “Just reviving the energy, reviving the spirit. Dick Rowland was the catalyst for the destruction. He was the kid they tried to hang… just an aspiring kid shining shoes. ‘Dicky Ro,’ shortening it and making it a nickname… I don’t take it lightly. It’s really a responsibility I take on to get the word out to as many people as I can.”

The sense of community among Tulsan poets and musicians stands strong. As a result, the Hip Hop community has grown steadily over the past few years, Simon says, because it has been bolstered by the local history.

“I have a relationship with the venue owners, the DJs, the sound guy, the people that made the flyer, the food trucks that are outside that [have] our names on the menu – naming their food after the artists,” Simon said. “It’s a full-fledged community… These are the people that we work with outside of the show, the show is like the last part of it.”

The Oklahoma Eagle, in partnership with the University of Maryland Philip Merrill College of Journalism and the School of Journalism & Mass Communication University of Wisconsin-Madison, and the “On the Ground Reporting” project, collaboratively instructed participating journalism students through the process of publishing stories that focus on community groups and issues in Tulsa and Oklahoma. The class was led by Maryland associate professor and Washington Post staff writer DeNeen Brown, an Oklahoma native, who teamed with Eagle editors M. David Goodwin and Gary Lee.

To read other stories in the student project, visit https://theokeagle.com/on-the-ground-reporting/