MELINDA THOMPSON, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, THE OKLAHOMA EAGLE STUDENT JOURNALISM PROJECT

Marsha Campbell walks into an art history class at Booker T. Washington High School. The retired science teacher is substitute teaching today. She sits at her desk, slowly pulls out her blue copy of the book “The 1619 Project,” and sets it down with a “thunk.”

“I would let my children know, ‘I’m your substitute teacher, and you can always get my attention, and there are your assignments,’” Campbell said in an interview.

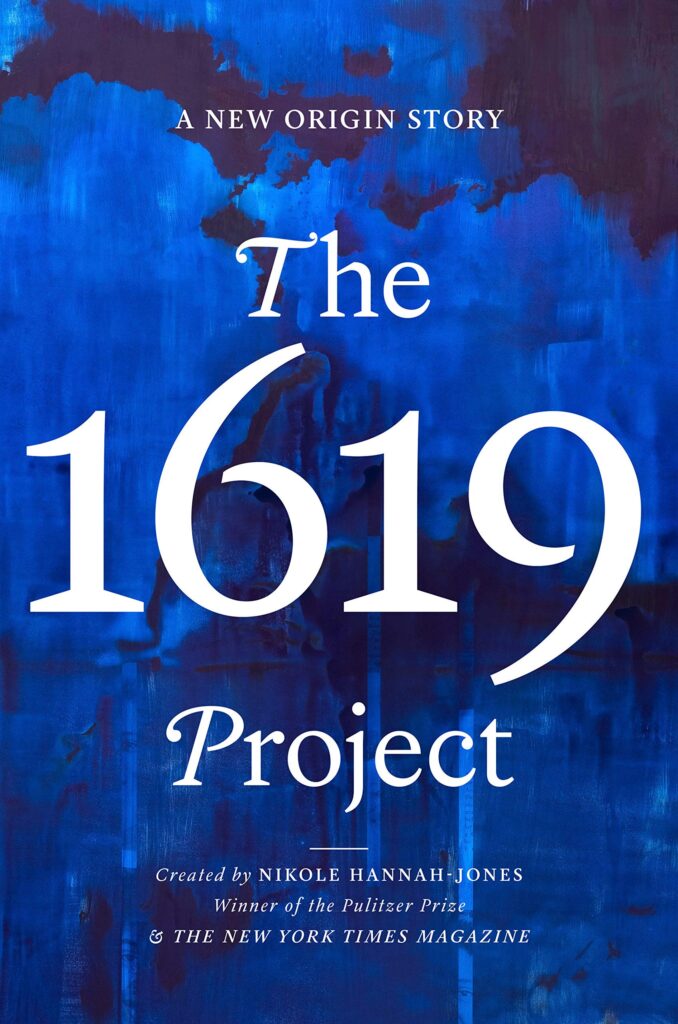

Campbell points to “The 1619 Project” and explains that it’s on a banned book list. “The 1619 Project,” created by The New York Times writer Nikole Hannah-Jones, is a collection of essays and poems that reframes the American narrative around the enslavement of people of African descent, and its legacy. The publication initially appeared in the New York Times magazine in 2019 and was published in book form in 2021. Hannah-Jones was awarded the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Commentary for her essay.

Campbell tells the students that the Tulsa Public School officials are banning books like this to dismantle public education, which is a danger to democracy.

“I would let ‘em know that they always have to be mindful of their elected officials and that they check their power, because they should not be given this much power,” Campbell firmly said. “They should not be given that.”

Across the nation, state legislatures are banning books about Black, Latino and LGBTQ history.

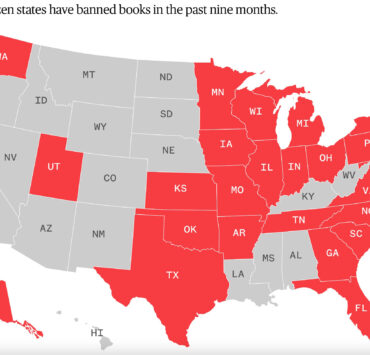

During a nine-month period, PEN America, a literary and free expression advocacy organization, found that 1,586 individual books have been banned by school districts nationwide, affecting 1,145 unique book titles. States like Florida, Texas, Washington and many states in the South are pulling books from school and library shelves related to race and sexual orientation. In Oklahoma, House Bill 1775, signed into law in 2021, severely restricts how race is taught in public schools.

The America Civil Liberties Union is fighting a lawsuit against the bill, saying that it prevents students from being able to have an “open and complete dialogue about American history.”

Oklahoma Senate Bill 1142, which became effective July 1, 2022, restricts public schools and libraries from offering books relating to sex and sexual orientation. It allows parents to put in a request for a book to be removed. If the request is not honored within 30 days, the parent could seek monetary damages with a minimum of $10,000 per day.

Since the law was passed, the Oklahoma Attorney General’s Office has reviewed more than 51 books for violations, including “Of Mice and Men” and “Lord of the Flies.”

On July 29, the Tulsa Public Schools removed two books – “Gender Queer: A Memoir” by Maia Kobabe and “Flamer” a graphic novel that draws on author Mike Curato’s real-life experiences – that they said violated this statute.

Oklahoma Library Association President Cherity Pennington said school libraries must provide students with age-appropriate materials and are supposed to show multiple viewpoints on controversial issues.

“Often in Oklahoma, the school library is the only library available to students, so banning library materials means that our students will not have access to the information they need to be informed citizens,” said Pennington.

LGBTQ Book Ban

Growing up with a high IQ of 171 in Oklahoma wasn’t easy for Campbell. She was an “integration guinea pig,” who was taught by high school teachers in elementary school.

She was smart. She took an IQ test at the psychiatric hospital because she was having trouble in school. The school system just allowed her to leave. Writing was never her strong suit, but she was an avid reader of books.

Before retiring in 2019 after 17 years as a TPS teacher, Campbell taught at McLain High School of Science and Technology in North Tulsa. Since then, she substitute teaches throughout the area. She is a member of the Citizens United for a Better Educational System that works with African Americans to help navigate the inadequacies of the Oklahoma education system. She dedicated her life to helping the school system, which is why she has a firm opinion against book banning.

Campbell has seen many students come and go through her classes. She’s noticed that now students can be openly gender fluid and explore their sexuality.

She recalls a recent example involving a student being subjected to taunts and misunderstanding.

The school year is beginning. Seventh graders are becoming eighth graders. Not only are grades changing, but puberty is beginning for these young students.

A familiar student walks into Campbell’s classroom. Something has changed that she didn’t immediately notice.

During the class, Campbell calls on the student by his name. The other students tease him making remarks saying, “Let’s call her by her name.”

Campbell said she didn’t know why the other students were making these comments until the student told her that he had transitioned. His classmates were using his dead name and misgendering him. A deadname refers to the name given at birth that has since been changed after transitioning.

Campbell took that seriously, saying that it was her responsibility to teach the students, and she needed to teach them how to respect and be kind.

In response, one of her other students felt comfortable enough to approach her and asked to be called by a male name instead of the name on the roster.

Campbell said that sexuality and gender are not talked about in classes. People figure out their own gender by having conversations with each other and reading books.

“Now, it’s no longer safe for them to talk about it or to read books about it,” she worries. “And they’re talking about banning and pulling those books from the libraries.”

Some of these books include, Kobabe’s “Gender Queer: A Memoir,” “Queer: A Graphic History” by Meg-John Barker and Julie Scheele, and “Two Boys Kissing” by David Levithan.

Racial Book Ban

As a scientist, Campbell believes it’s necessary for students to learn the truth. She’s not a history teacher, but for her, banning books about race paints an incomplete picture of United States history.

“They’re bringing up of book bans just, reiterates, that to me, it’s reflective of the Jim Crow,” Campbell said with a forlorn look. “Just reflective of reconstruction. The book bans remind me that the Daughters of the Confederacy got to write the history books.”

In her classes, Campbell stresses the importance of making the classroom an honest, truthful, and safe space to talk about issues that make people uncomfortable.

Kristi Williams, North Tulsa advocate and chairperson of the Greater Tulsa African American Affairs Commission, emphasizes the importance of showing Black children in history.

“They need to see themselves in history, and not always, as slaves or non-contributors to this country,” Williams said. “They need to see that greatness, and when you don’t see that, it affects you as a person.”

Teach The Whole Truth

Campbell initially taught mostly Black children in Tulsa. But as a substitute teacher, she now teaches Black, white and Hispanic children as she jumps from school to school.

When she’s teaching, she acknowledges the diversity of her classes and wants her students to learn history to the fullest to understand different communities’ grievances.

“Then they can say, well, ‘That’s my friend, and that’s my friend, and I feel bad about what happened, but that’s not who we are. How can we make it better? How can we improve the outcome? How can we continue a hopeful path different than that we are on now?” Campbell quotes from her students.

When she substitutes history classes, she thinks that if you’re not going to teach the whole truth, you shouldn’t teach history. Campbell said that book bans are a way of erasing history and the experiences of her ancestors.

“I believe in this country, and I don’t think that banning books is true to the nature of the freedoms that this country was founded on,” Campbell said. “Even though I wasn’t a beneficiary of the freedoms, and my ancestors weren’t, I still believe in the ideals of this country. And I am hopeful that your generations, that generations in the future are going to fulfill the dream or the – fulfill the ideals of the founding of our nation. And that banned book is never an answer.”

Campbell grew up in a time when she couldn’t drink from the same water fountain as white people, and she’s seen this backlash in Oklahoma where the political pendulum swung towards President Donald Trump’s politics after President Barack Obama’s two terms in office. And yet, she stays hopeful for the future and believes newer generations can put back the pieces. In her vision, that future would not involve banning books.

Banned Books In The U.S.

PEN America, , a left-of-center nonprofit dedicated to promoting its conception of free speech and journalism, has compiled an index of banned books in the United States. So far, the only Oklahoma school identified is Bristow Public Schools, which has banned 43 books from July 1, 2021, to March 31, 2022. Here are other findings:

2 million: U.S. public school student population impacted by book bans

2,899: U.S. public schools with book bans

1,586: Instances of individual books being banned

1,145: Banned book titles

819: Banned books that are fiction

874: Banned authors

467: Books where protagonists or prominent secondary characters are of color

247: Books that directly address issues of race and racism

198: Banned illustrators

86: U.S. public school districts with book bans

26: Number of states with book ban laws

9: Banned translators, impacting the literary, scholarly, and creative work of 1,081 people altogether.

About This Project

The Oklahoma Eagle, in partnership with the University of Maryland Philip Merrill College of Journalism and the School of Journalism & Mass Communication University of Wisconsin-Madison, and the “On the Ground Reporting” project, collaboratively instructed participating journalism students through the process of publishing stories that focus on community groups and issues in Tulsa and Oklahoma. The class was led by Maryland associate professor and Washington Post staff writer DeNeen Brown, an Oklahoma native, who teamed with Eagle editors M. David Goodwin and Gary Lee.

To read other stories in the student project, visit https://theokeagle.com/on-the-ground-reporting/