North Tulsa’s health care stretches back more than a century.

ABOUT THIS SERIES

The Oklahoma Eagle’s “Of Greenwood” series is part of our 2nd Century Campaign, which commemorates the hundredth anniversary of this African American newspaper. This series is made possible through our partnership with Liberty Mutual Insurance.

By Victor Luckerson, The Oklahoma Eagle

Photography by Basil Childers

Dr. Runako Whittaker didn’t expect to stay in Tulsa. The pediatrician came to the city for her residency in the year 2000 in order to get help to pay off her student loans.

The federal government was offering financial relief to med school graduates who worked in medically underserved areas, and North Tulsa, which had lacked a full-service hospital since the 1960s, certainly qualified. For Whittaker, Seattle was home, and she expected to be back on the West Coast soon enough.

But in North Tulsa she found a community she wanted to help, and a legion of older doctors who wanted to help her.

“There have been several Black physicians here in town who have served as mentors for me,” Dr. Whittaker said, citing longtime North Tulsa neurologist Dr. Jerome Wade as an especially strong influence. “He was always open for questions and advice.”

Dr. Whittaker and Dr. Wade serve as recent links in a lineage of North Tulsa health care that stretches back more than a century. This community has long been served by a small but dedicated group of physicians who strive to protect the health and well-being of their neighbors.

For decades, North Tulsa doctors dealt with inferior equipment and poorer facilities than their white counterparts. They were excluded from both medical schools and medical societies in the state. After Jim Crow was slowly beaten back in the 1960s, a new set of challenges emerged, with Greenwood’s sole hospital being shut down and mass divestment from the community creating new health challenges as easy access to nutritious food evaporated. But through it all there have been doctors ready to answer the emergency call in this part of town.

Dr. Whittaker’s father grew up in Okmulgee and told her stories about Greenwood’s storied history as “Black Wall Street” when she was a child. Today, she still feels inspired by the community doctors who came before her. “Those of us that are practicing today,” she said, “have continued the work and the legacy of those physicians.”

‘The most able Negro surgeon in America’

Though Greenwood traces its origins to 1905, the community lacked a hospital for more than a decade after its founding. Blacks were excluded from white hospitals because of the new state’s segregation laws, instead undergoing serious and sometimes fatal operations within their own homes. In 1917, the Booker T. Washington Hospital opened on Archer Street. J.H. Goodwin, the grandfather of Oklahoma Eagle publisher James Osby Goodwin Sr., was on the hospital’s original board of directors. But the facility did not have the resources offered to the local white hospitals of the era. When the Spanish flu struck Greenwood in the fall of 1918, for example, hospital staff had to erect makeshift beds on the building’s floors.

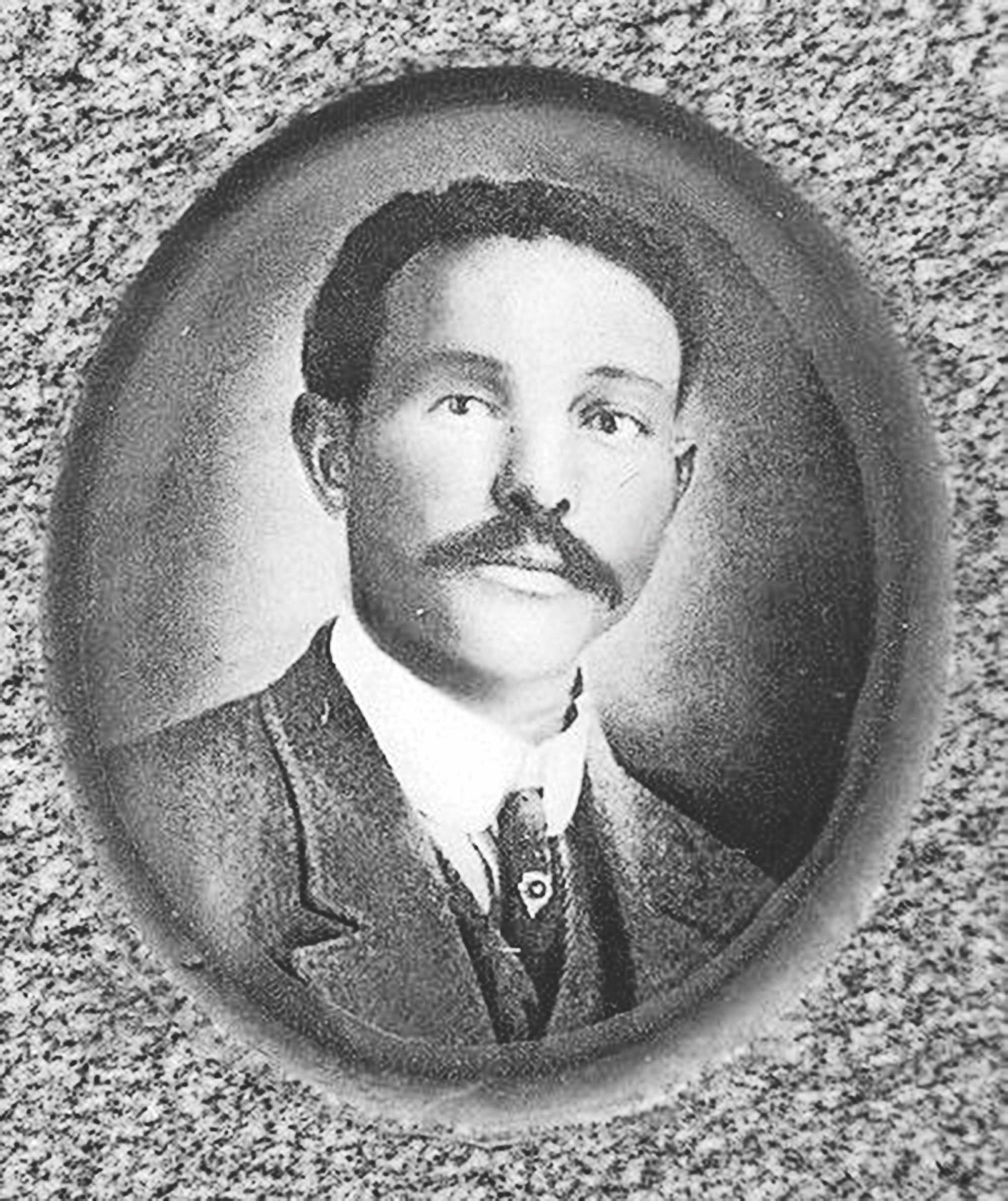

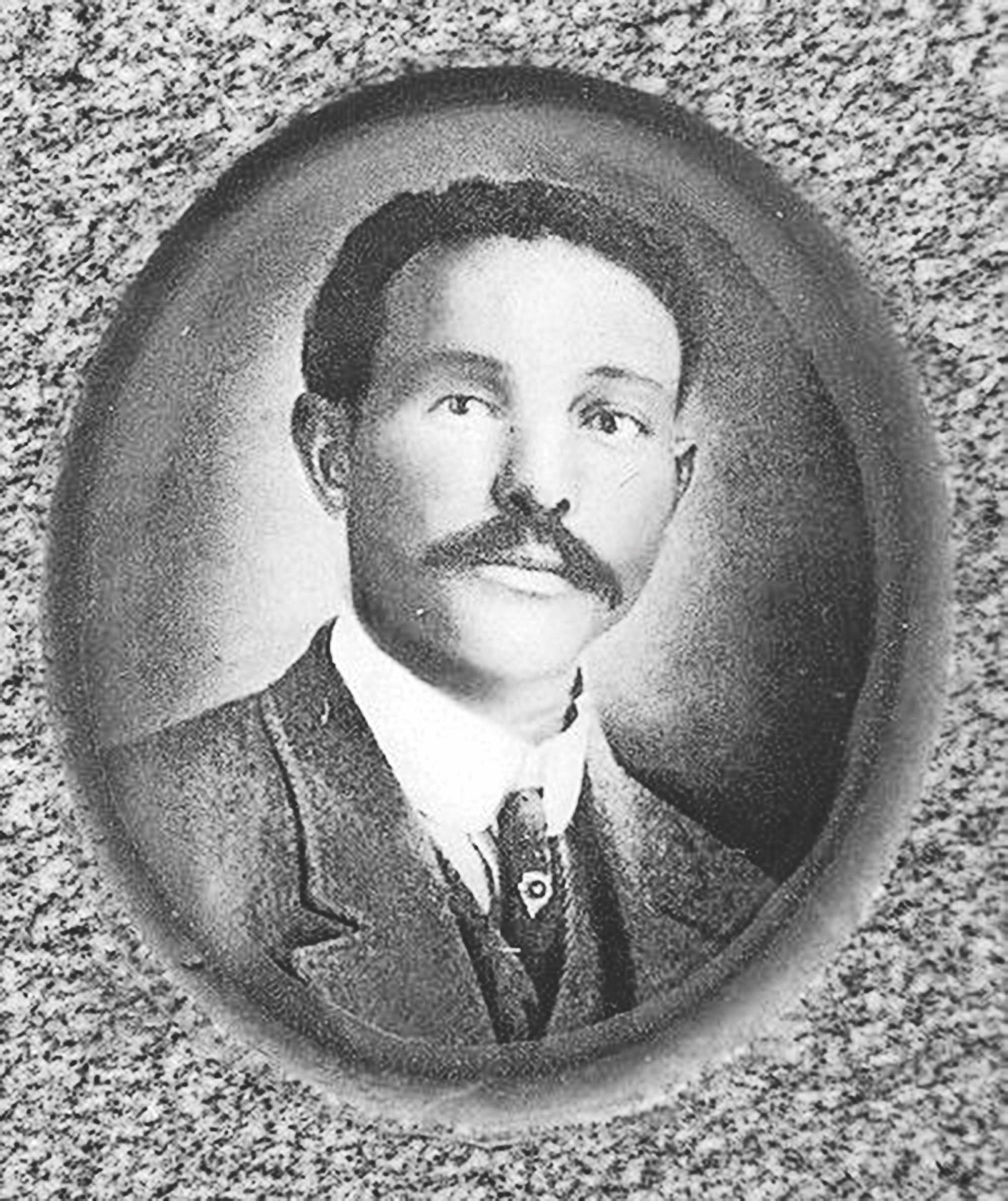

Even working with so little, Greenwood physicians had an outsized impact. In 1921, there were at least 15 doctors serving a neighborhood of roughly 11,000 people. Dr. A.C. Jackson became the most prominent among them. A Memphis native who came to Oklahoma as a child around 1889, Jackson became such a skilled physician that Will and Charlie Mayo of the famed Mayo Clinic decreed him “the most able Negro surgeon in America.”

For the people who knew him, though, Dr. Jackson was a kind and friendly soul, who was often seen making housecalls in his Ford Model-T, delivering babies and caring for the sick. Wilhelmina Guess Howell, a niece of Jackson’s, later recalled how he saved her from a bout of scarlet fever at age 8.

In 1921, when Greenwood was set aflame by a white mob, Dr. Jackson no doubt would have played a vital role in caring for the wounded. But a group of white men, some of them wearing police badges, descended on his block on Detroit Avenue on the morning of June 1.

The men demanded that Dr. Jackson exit his home, likely under the pretense of taking him to one of the internment camps where Black people were being detained. But when he stepped outside with his hands up, Dr. Jackson was shot twice at point-blank range. He became the most famous casualty of the day’s vicious violence.

Greenwood’s hospital was also burned to the ground that day, forcing the community to convert the area high school into a temporary field hospital manned by neighborhood doctors and the American Red Cross, which opened a Disaster Relief Headquarters. Dr. R.T. Bridgewater, a Greenwood doctor whose home was looted during the massacre, recalled that he did not even have time to begin cleaning up his belongings, because he was so busy treating his neighbors’ injuries.

“I worked extremely hard for three or four days after the riot,” he said. “I almost collapsed.”

Moton Memorial Hospital

Working in conjunction with the Red Cross, Greenwood leaders opened a new nine-room hospital less than a year after their neighborhood was burned to the ground. The new facility was named after Maurice Willows, the Red Cross director in Tulsa and who spearheaded relief efforts. Willows had been one of the only white allies to Black Tulsans as city leaders tried to seize their land after the massacre, so the community named the facility in his honor.

“The hospital can and should be made self-sustaining,” Willows wrote in a 1922 disaster report.

It wasn’t just doctors who helped achieve the goal of sustainability either – Dimple Bush, a Greenwood nurse who survived the massacre, became the administrator of the new hospital and was widely respected for her business acumen.

Maurice Willows Hospital eventually became Moton Memorial Hospital, named after Tuskegee Institute President Robert Moton, who succeeded the school’s founder Booker T. Washington after his death in 1915.

But by the 1940s, due to overcrowded conditions and a lack of basic housing amenities such as indoor plumbing, Greenwood residents had health problems that Moton alone couldn’t solve. Tuberculosis outbreaks were frustratingly common in the cramped quarters of Greenwood’s low-rent housing, and the infant mortality rate was more than double that of white children.

Moton had only 50 beds to treat all the ailments of a Black community that by then totaled 25,000. White hospitals accepted only a small number of Black patients in segregated basement wards. Most of them refused to accept pregnant Black women outright.

“The number of deaths among Negroes is out of proportion to their ratio in the population,” the Urban League concluded in a 1945 study.

Top-notch Black doctors, inferior equipment

Still, Greenwood’s doctors did the best they could. Dr. Charles Bate, a longtime North Tulsa physician and surgeon, who began practicing when he arrived in 1940 from the famed historically Black Meharry Medical College in Nashville, recalled the many challenges of serving the neighborhood in his 1986 memoir, “It’s Been a Long Time. And We’ve Come a Long Way.”

In those early days of his career, midwives delivered babies without prenatal care; X-rays were hard to come by; and many expectant mothers had never had a physical exam until the day their baby arrived.

“This isn’t any exaggeration of the times and facilities,” Bate wrote. “The men worked and hoped.”

Often, the Moton staff had to rely on the Greenwood community to raise funds for much-needed equipment, such as X-ray machines and air conditioners, because the city of Tulsa didn’t budget for them. But Dr. Bate was proud of the work he and others did at the hospital against long odds.

“Moton has had a glorious past and provided great service to the Black community,” Dr. Bate wrote. “Black babies who would have perished in many cases were delivered by Black doctors in Moton.”

In 1967, Moton was shut down, even as Dr. Bate, other Black doctors, and members of the North Tulsa community fought to keep it open.

“There are a lot of hard-working decent Negro people whose only sin has been being poor; they have just made small contribution s to society, but they have not detracted from society,” he wrote in a last-ditch plea in the Tulsa Tribune. “They need a decent place to end their lives.”

Different generation, same challenges

When Dr. Runako Whittaker came to Tulsa, her residency was at Morton Health Services Center, the medical facility that replaced Moton Hospital in the late 1960s. Unlike a traditional hospital, Morton lacks an emergency room and urgent-care center.

Despite practicing medicine decades after Dr. Bate, she would find herself facing some of the same challenges.

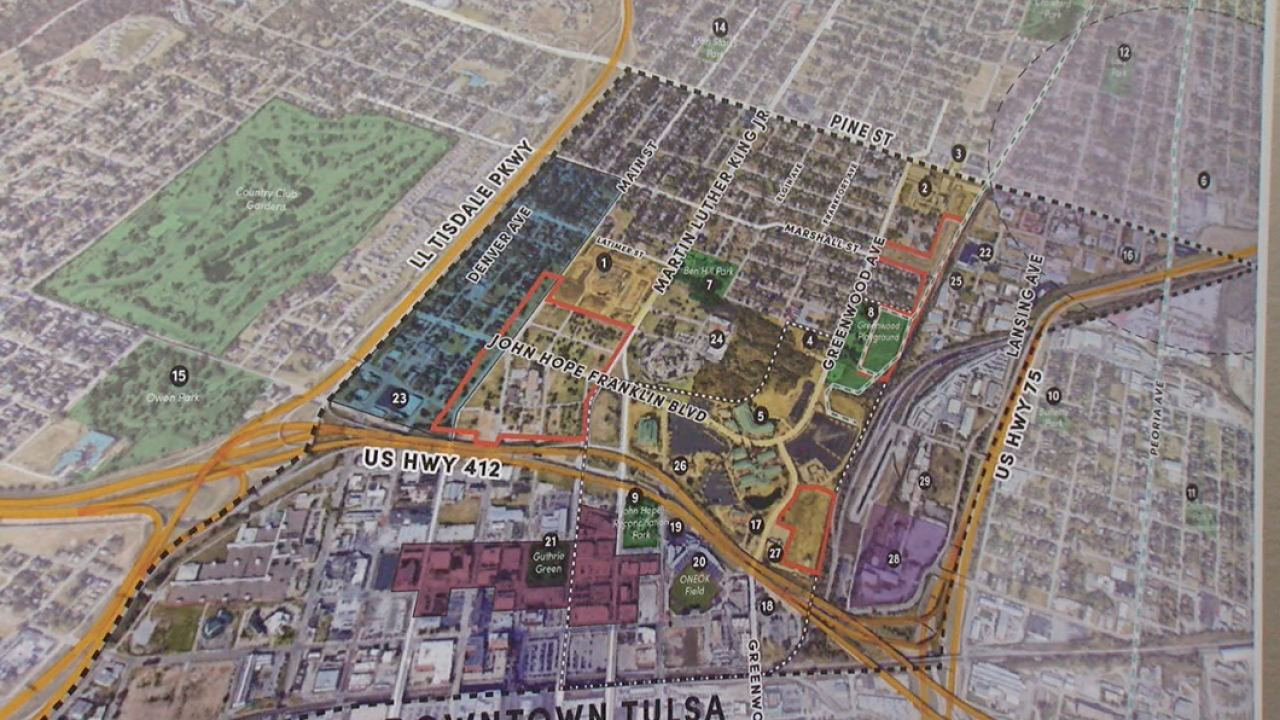

The issue in North Tulsa now is not overcrowding but rather a sprawling urban community that is not supported with vital services. Much of North Tulsa has been a food desert for the last decade, lacking nearby access to a grocery store.

Dr. Whittaker says this has knock-on effects for residents of all ages.

“If you don’t have access to nutritious food, then that impacts your health,” she says. “You’ll see things like obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure. And those aren’t just limited to adults. As a pediatrician, I see these conditions with children and adolescents…if they don’t have any place to go to get that healthy nutrition, then it’s almost like you’re in a Catch 22.”

In 2012, Whittaker opened her own pediatric practice at Westview Medical Center, located at the intersection of 36th Street North and Martin Luther King Boulevard. The center has been open since 1984, when it was founded by a group of six Black health care professionals who wanted to provide care for Tulsa’s underserved Black community.

There, she cares for somewhere north of 2,000 young patients (they get cartoon stickers instead of lollipops to cut down on sugar intake). Dr. Whittaker says it’s important that Black patients are able to receive Black doctors if they so choose, especially because of a long history of health systems providing poor care to Black citizens – not only in Tulsa, but across the United States.

“There’s a lot of distrust, and rightfully so, on the part of African Americans towards the healthcare system,” Dr. Whittaker says. “You can read any article about the disparities in Black maternal health. And, so, when it comes to African Americans going to the doctor, they want to know that their voice, and their concerns are going to be heard. And that’s more likely to happen if they have a physician that looks like them.”

Long way to go

The city of Tulsa has a long way to go to achieve equitable health outcomes for North Tulsa residents. There is a life expectancy gap of more than 10 years between some ZIP codes north of Greenwood Avenue and the more prosperous ZIP codes of South Tulsa. And according to a recent report in the Wall Street Journal, the infant mortality rate for Black babies in Tulsa today is 2.5 times higher than the rate for white ones. That’s actually higher than the ratio the Urban League found in 1945.

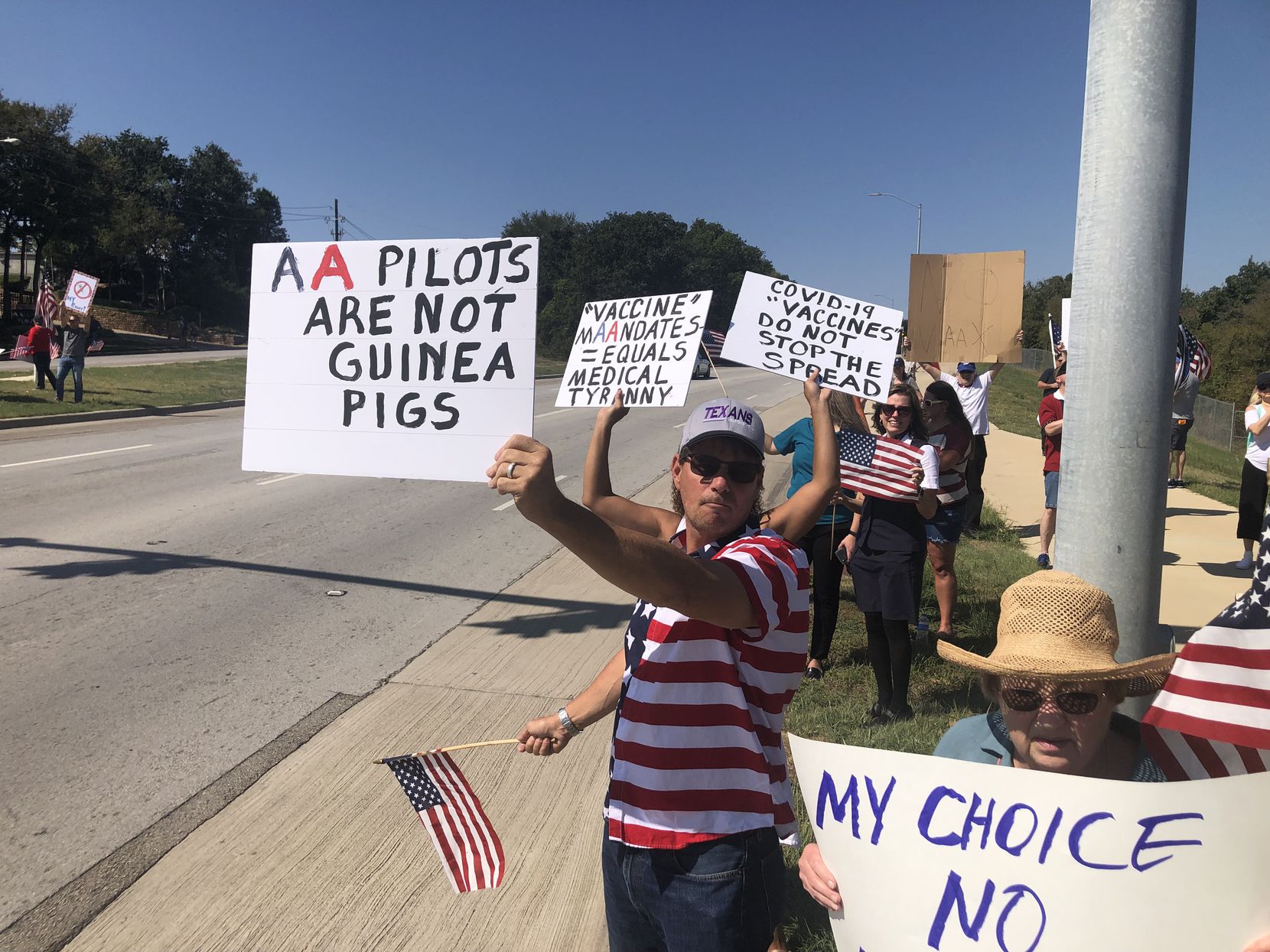

Since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, many North Tulsa leaders have worked to ensure the health of their community against the deadly virus.

At an August press conference, the Rev. Dr. Robert Turner, the former pastor of Vernon AME Church in Historic Greenwood, urged his neighbors to get vaccinated. A Tuskegee, Alabama, native, Turner noted that the notorious syphilis experiments conducted on Black men in his hometown hit especially close to home, but that he trusted the COVID-19 vaccine.

“It works,” he said.

More recently, in September, the Terence Crutcher Foundation offered free vaccines at the 36th Street North Event Center as part of a day of service. While Black people have suffered disproportionately high mortality rates from COVID-19 nationally, in Tulsa County, where they comprise about 11% of the population, they comprise about 9% of deaths.

Organizations like the George Kaiser Family Foundation aimed at closing the health gap between North and South Tulsa, such as providing funding for community health centers and offering hypertension screenings to people in low-income ZIP codes.

Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum has regularly invoked the life expectancy gap in the city as one of the key disparities he wants to thwart. But the biggest game-changer for North Tulsa is likely to come from the expansion of Medicaid in Oklahoma, which was approved by voters in a June 2020 ballot initiative. Roughly 190,000 additional Oklahomans now qualify for the government-funded health care coverage, and 120,000 people have applied to receive benefits.

Changes are slowly coming

There are other new, positive signs for the community. The recent opening of the Oasis Grocery Store on North Peoria Avenue has made it easier for Dr. Whittaker’s patients to access nutritious foods. “Now I can tell them exactly where to go and they don’t have to travel far,” she says.

There’s also a greater effort among doctors to collaborate in engaging the community. Dr. Whittaker is part of a group planning to relaunch an Oklahoma state branch of the National Media Association, an organization that has represented the interests of Black physicians for more than 100 years. Dr. A.C. Jackson was the vice president of the Oklahoma state chapter at the time of his murder in 1921. It’s fitting that the new chapter will be called the A.C. Jackson State Medical Society.

“It felt very appropriate,” says Dr. Nicole Washington, a Tulsa psychiatrist who is also part of the new group. “Being that this was the 100-year commemoration of the Tulsa Race Massacre.”

The new statewide organization, which already includes members in Tulsa, Oklahoma City, and Lawton, will help Oklahomans find Black physicians in specific fields and host educational sessions on healthy living. Encouraging vaccinations against COVID-19, which has disproportionately impacted Black communities, is also a priority.

Staying home in North Tulsa

The group will also work to reach out to Black medical school students and residents in Oklahoma so that they can receive the same mentorship and guidance earlier generations did when they arrived here in Tulsa.

“The last year or so has shown us that we need each other,” Dr. Washington says. “When we have Black students in those schools, we need to provide a sense of community to them so they don’t feel like I have to get out of Tulsa as soon as I graduate.”

Dr. Washington, just like Dr. Whittaker, thought she would be leaving Tulsa after she finished her medical training. But the city has a way of convincing people it’s a place, and a people, worth fighting for.

More than 20 years later, Dr. Whittaker has never thought of moving her practice anywhere else.

“I love working in North Tulsa, with North Tulsa,” Dr. Whittaker said. “I just felt at home, and I wanted to stay home.”