COMMENTARY

Ross D. Johnson

The Oklahoma Eagle

Illustration The Oklahoma Eagle

Personal belongings and household goods had been removed from many homes and piled in the streets. On the steps of the few houses that remained sat feeble and gray Negro men and women and occasionally a small child. The look in their eyes was one of dejection and supplication. Judging from their attitude, it was not of material consequence to them whether they lived or died. Harmless themselves, they apparently could not conceive the brutality and fiendishness of men who would deliberately set fire to the homes of their friends and neighbors and just as deliberately shoot them down in their tracks.

TULSA WORLD DAILY, JUNE 2, 1921

Don Ross, then Oklahoma State Representative, serving District 73, gave voice to a city and a nation whose demands for accountability and remedy for the sins of the state of Oklahoma during spring 1921. The prologue of the 2001 Report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, authored by Ross, framed the historic atrocities committed against Black Tulsans, the depth of impact and a call to be compelled by our country’s moral obligation to reveal those responsible and subsequently commit to applications of remedy.

In the four-and-a-half pages of the prologue, Ross skillfully shepherded readers along a journey of awareness, outrage, and proposed remedies.

The state legislator revealed how he learned about the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, at the approximate age of 15, and his initial naïve refusal to accept the facts offered by Booker T. Washington High School teacher and Race Massacre survivor W. D. Williams. Ross shared that the day following his discussion with Williams was one of profound meaning, inspiring a commitment to not merely become familiar with the chronology of events, but to consider how the related facts would shape his life. Williams’ key question to Ross was “What you think?” Answering that question guided much of Ross’ work in adult life.

Although more than 22 years has passed since the report was published, St. Rep. Regina Goodwin, of Tulsa’s District 73, and civic leaders throughout Oklahoma have not forgotten the spirit and substance of Ross’ prologue, the personal accounts of Black Tulsans victimized, the breadth of property destruction, the chronology of hate-inspired violence, and the complicit actions by city and state officials.

Goodwin has championed the proposed remedies detailed in the 2001 Report since taking office in July 2015. A legislator who has well-earned a reputation as a stalwart supporter of equity and justice, Goodwin has remained committed to many of the proposed remedies.

Goodwin, a daughter of Greenwood, recounted the recommendations from the 2001 Race Riot Report: survivor, descendant and victim compensation; education scholarships for low-income Tulsans; substantive economic development and a memorial that properly captures the legacy of the Historic Greenwood District community.

Before the Oklahoma House General Government Committee on Oct. 5, Rep. Goodwin led the Interim Study, “Updated Status and Progress on the 2001 Tulsa Race “Riot” (Massacre) Commission Report” review, centered within an examination of the 2001 Tulsa Race Riot (Massacre) Commission Report recommendations and the progress achieved since the report’s original filling in 2001.

“While this study is long overdue, we are blessed to have eyewitnesses, our great survivors, more than 100 years later, among us,” said Goodwin. “We will stare American history in the face to truthfully discuss recommendations, challenges, reparations, and policy. Right solutions lead to long-sought restorative justice.”

The Interim Study report, built on the 2001 Report recommendations, is now informed by recent data from historians and contributors, who passionately shared their findings throughout the three-hour session.

1921 Tulsa Race Riot Commission appointees, Dr. Vivian L. Clark-Adams and James ‘Jim’ Lloyd, appointed by then Tulsa Mayor Susan Savage in 1997, offered a summary introduction for attendees. Clark-Adams framed the Interim Study as an accounting of progress and accountability, emphasizing the significance of reparations for 1921 Massacre survivors and descendants.

“The reason the commissioners listed the reparations for survivors, and reparations for descendants as one and two is because they were the most important things, we think, that’s needed to restore what was stolen from this community,” said Clark-Adams. The legacy commissioner reminded attendees that reparations was not a demand unique to Black Tulsans, by chronicling the restorative efforts related to Rosewood, Fla., Native American tribes, Alaskan natives, Hawaiian natives and Japanese/Japanese Americans for past atrocities.

James Lloyd, an attorney, also appointed as a commissioner in 1997, reminded state officials of the moral and ethical obligation for repair and rebuild. Lloyd concluded his remarks with a biblical reference, citing Luke 19:8, “Look, Lord! Here and now I give half of my possessions to the poor, and if I have cheated anybody out of anything, I will pay back four times the amount.”

Steven Bradford, California State Senator, District 35, recounted the 100-year journey undertaken by the Bruce family to return ownership of Bruce’s Beach to the closest living legal heirs of Charles and Willa Bruce, after decades of legal challenges.

As is the shared sentiment of Black Tulsans, Bradford noted that “the Bruce family was robbed of their land, their business, their dignity, and the opportunity to pass on generational wealth to their descendants.”

James ‘Jim’ Goodwin, Esq., 1921 Massacre descendent and publisher of The Oklahoma Eagle newspaper, offered a pointed critic of progress achieved since the publishing of the 2001 Commission Report and unfulfilled promises of restoration. Goodwin, after characterizing the violent acts committed against Black Tulsans in 1921 as ‘domestic terrorism’, directed his concern towards the city’s and state’s “Token expressions of apologies and token remembrances, marking this infamous time.”

Laura Pitter, deputy director of the U.S. Program at Human Rights Watch, shared a comparable sentiment in US: Failed Justice 100 Years After Tulsa Race Massacre, a Human Rights Watch report in May 2021. In response to local Tulsan perceptions of Greenwood Rising, Pitter offered, “Creating a museum to showcase victims’ experiences can be part of reparations… But when it’s done in lieu of or at the expense of other types of necessary repair, and without properly consulting the survivors or the descendants it can be very damaging.”

The path forward, according to Mr. Goodwin, must be far more substantively paved with economic development initiatives that yield measurable outcomes, a state memorial that rightfully acknowledges the sins of the past and the resilience of Black Tulsans and tax incentives to encourage building a sustainable economy.

Eric Miller, professor of law at Loyola Law School at Loyola Marymount University (Los Angeles), highlighted the insight gained since the 2001 Massacre Report was published. Miller noted the increased number of 1921 Massacre Survivors identified, historians’ work to more accurately frame the scope of the historic district destruction and governing agency complicity. According to Miller, “Armed mob patrols,” referenced within artifacts not available to initial commission members, were authorized to actively capture, kill, and incarcerate Black civilians during the 1921 Massacre. “A conspiracy of silence”, as described by Miller, blocked most efforts to identify those culpable and suppressed evidence regarding the crimes committed against Black civilians.

A letter, not available to commissioners for the 2001 Massacre report, from Major C. W. Daley to Lieut. Col. L. J. F. Rooney, July 6, 1921, detailing the Oklahoma State National Guard’s complicity in the mass arrests and civil rights violations against Black Tulsans, according to Miller, served as further justification for demands of state accountability. “Gathering up all negroes,” Miller noted, was the instruction provided by Daley.

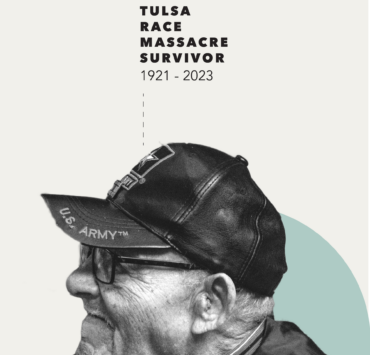

Damario Solomon-Simmons, attorney, who has represented race massacre survivors, Viola Ford Fletcher, 109; Lessie Benningfield Randle, 108; and Hughes Van Ellis, 102, throughout their years-long legal challenge for restoration and victim compensation. Solomon-Simmons drew emphasis on the topic of restorative justice, an approach to justice that focuses on responsibility, accountability and restoration. The Tulsa-based attorney, Solomon-Simmons, whose “ministry” is law and “passion” is justice, reminded all that restorative justice is “the basis of our civil justice system.”

The moral imperative, Solomon-Simmons noted, bolstered by well-established legal precedent, must compel the state of Oklahoma to satisfy insurance claims denied, approve tax abatements, provide tuition-free scholarships, and implement hiring preferences for survivors and descendants.

Dr. Robert Placido, vice chancellor of Academic and Student Affairs for the Oklahoma Regents for Higher Education, and Dreisen Heath, senior coordinator in the United States Program at Human Rights Watch, provided insight about the effect of restorative policies, once employed, regarding education. Placido reminded event attendees of Rep. Goodwin’s leadership and the significant benefit of her fight to secure $1.5 million of funding to support the Tulsa Reconciliation Education and Scholarship Program. The vice chancellor also announced that the program recently awarded a full scholarship to the “first documented descendant” this year, a goal far less than the intended 300 recipients envisioned.

Heath, who has advanced well-regarded research and authorship about the harms related to the Race Massacre, provided necessary context about available scholarships and funding. House Bill 1178 (1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act), Heath noted, and the related Tulsa Reconciliation Education and Scholarship Trust Fund, were championed in spirit to address the historic disparity created as a result of the Race Massacre. In practice, Heath marked, the priority of funding was lacking, and/or the priority of hiring preferences.

Chief Amusan and Kristi Williams, members of the 1921 Graves Investigation Public Oversight Committee, framed a sharp critic of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Investigation committee’s efforts to date, focusing on the lack of transparency, rightfully perceived attempts to delay excavations and a general disinterest in uncovering the sins of the state of Oklahoma. Amusan and Williams are both descended from victims of the 1921 Race Massacre.

Amusan’s and Williams’ concerns were centered within a denial of dignity of Tulsans murdered during the Race Massacre, reported by The Oklahoma Eagle in Nov. 2022. The committee members have challenged city of Tulsa officials’ commitment to reconciliation, citing mass grave excavations delays and the scarcity of information provided to oversight committee members as required by Oklahoma statute.

In the absence of a clear path forward to identify potential mass grave sites, a consistent approach to identifying the exhumed, and an open dialogue with Tulsans is key, the oversight committee members shared, to restoring the faith and trust of Tulsans.

“If we can get it right in Oklahoma, we can get it right anywhere,” declared Dr. Tiffany Crutcher, during closing remarks. A Race Massacre descendent and founder of the Terence Crutcher Foundation, she has been an unwavering voice for restorative justice for Race Massacre survivors and Tulsans disenfranchised by economic, civic, and legal institutions. Crutcher’s remarks were not merely an impassioned parting sentiment, intended to evoke optimism amongst event attendees and those who streamed the session. Her [Crutcher] call to ensure that “these survivors, our descendants… receive the proper repair, the proper respect and the proper restitution” was a stark reminder that the 2001 Commission’s work was incomplete, that the city’s and state’s rhetoric has once again fallen far too short of a moral obligation…. And that Tulsans have not forgotten.