LOCAL & STATE

Gary Lee

The Oklahoma Eagle

Photo The Oklahoma Eagle and Sam Levrault Media

Two and a half years ago, Hughes Van Ellis appeared on the national stage and recounted critical episodes from his life story: of a childhood of poverty; of the discrimination he had faced when he came home from military service in World War II, and of the battles for justice he had fought over the years. The most poignant story he told was of being an infant in the community of north Tulsa in late Spring of 1921, when a massacre, highlighted by the murder of over 300 people, wiped out the entire neighborhood.

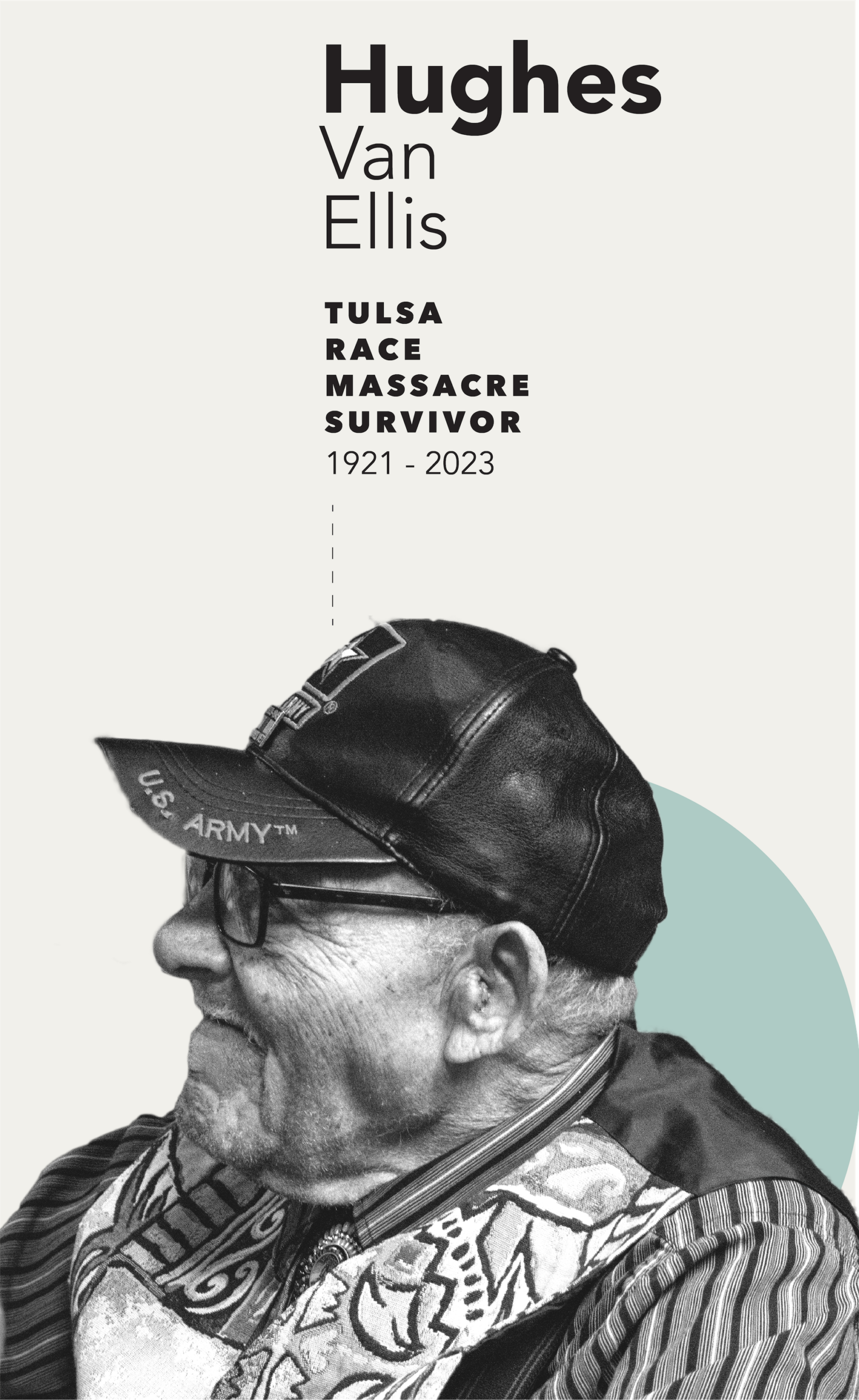

More than one hundred years old when he told the story, Van Ellis wore his signature black leather U.S. Army cap and the determined look of a man who was proud and humble of the journey behind him and was pushing forward for a greater future.

Van Ellis, the youngest of the three survivors of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, died in his sleep on Oct. 9 in a Veterans Affairs hospital in Denver, Colo. A cause of death was not announced, but family members said that Van Ellis was being treated for cancer that had recently spread to his brain. He was 102.

The narrative he shared of his life struck chords that were familiar among Black Americans. Many had likely heard a version of it before, maybe from a father or grandfather who had struggled through the challenging span of years of racial oppression, the Jim Crow segregation era, and the civil rights movement, along with all the humiliation those years had brought.

A man full of optimism

But two aspects of Van Ellis’ presentation of his personal history stand out. One was his audience. At the time, he spoke before Congress, addressing national legislators and members of a judiciary subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives.

As a survivor of the 1921 Race Massacre, he was making a plea that through legislation, lawmakers could bring about some justice for him and the other two survivors his 109-year-old sister Viola Fletcher and 108-year-old Lessie Benningfield Randle – that the courts had denied. Van Ellis’ speech, along with those of others who testified, was broadcast nationally from the chambers of the U.S. Congress. Listeners tuning in across the country heard – and clung to – his words.

“My childhood was hard, and we didn’t have much. We worried what little we had would be stolen from us, just like it was stolen in Tulsa. You may have been taught that when something is stolen from you, you can go to the courts to be made whole; you can go to the courts to get justice. This wasn’t the case for us,” Van Ellis told the congressional panel.

Another aspect of Van Ellis’ testimony that made it remarkable was his eternal, heartfelt optimism. Despite a life marked by hardship and discrimination, he expressed a joyous confidence in humanity and believed that he – and other victims of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre – would get justice.

“We are asking for justice for a lifetime of ongoing harm caused by the massacre,” he said. “You can give us the chance to be heard and give us a chance to be made whole after all these years and after all our struggle,” said Hughes Van Ellis.

Everybody’s uncle

Van Ellis was known as “Uncle Redd” throughout Tulsa – and almost everywhere he went. It was a nickname that suited him to a tee. To be sure he took on many roles- father, husband, breadwinner, foot soldier for justice. But, always donned in his cap with a U.S. Army emblem, comfortable, often stylish clothes, and a broad smile that took over his face, Uncle Redd cast a figure of every Black American’s wizened older relative.

A laborer for most of his adult life, Van Ellis was an everyday man whose life story and voice were lifted onto the global stage and captured in news headlines and documentary programs because of when and where he spent the first few months of his childhood. As he shared in his congressional testimony, Van Ellis lived with his family in north Tulsa in early 1921. When an angry white mob invaded the Black community of Greenwood in late May and early June 1921, Van Ellis’ family resided in the neighborhood.

“Because of the massacre, my family was driven out of our home,” Van Ellis told members of the congressional panel. “We were left with nothing. We were made refugees in our own country.”

Hard knocks and triumph

Hughes Van Ellis was born in Holdenville, Okla., on Jan. 11, 1921. His parents settled in Tulsa until he was around five months old. Following the Tulsa Race Massacre, the family fled Tulsa, leaving their home and possessions. Van Ellis was drafted and served in an all-Black combat unit in World War II. He and his wife, Mable Ellis, married in 1942. They made their home in Oklahoma City.

Van Ellis worked several jobs to support his wife and seven children: a sharecropper, a mechanic, a janitor, a gardener, and a gas station attendant. He and his family eventually settled in Denver. In addition to his sister, Fletcher, and Ellis’ survivors include daughters Mallee and Muriel Van Ellis. Van Ellis’s funeral services are pending.

Of all the events of his life, Van Ellis seemed most proud of his military service. Ellis fought for his country in World War II, serving in an anti-aircraft unit in a segregated U.S. Army.

“I did my duty in World War II. I served in combat in the Far East with the 234th AAA Gun Battalion. We were an all-Black battalion,” he told the congressional panel in ‘2021. “I fought for freedom abroad, even though it was ripped away from me at home, even after my home and my community were destroyed. It is because I believed that America would get it right in the end,” said Van Ellis.

In public appearance, he always wore a black cap with a military emblem and the words U.S. Army across the top.

“It is as if he wanted to give a constant reminder that he had served his country and, despite being treated unjustly, was proud of it,” said state St. Rep. Regina Goodwin, (D-73) and longtime advocate for Van Ellis and the other Race Massacre survivors and descendants.

A crusade for justice and compensation

Even before his testimony before the May 2021 congressional panel, Van Ellis had already engaged in a high-profile campaign for compensation for himself and other survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre.

In 2005, he joined other survivors seeking reparation before the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court declined to hear the case appeal after federal courts ruled that the statute of limitations had expired. Dozens of survivors stood dejected outside the Supreme Court after that ruling.

In September 2020, massacre survivors, including Van Ellis, filed a lawsuit in Tulsa claiming that in 1921, the city, the county, the Oklahoma National Guard, and other officials caused “public nuisances” when they failed to defend Tulsa’s Black community from a white mob that descended on the Greenwood community.

The lead attorney, Damario Solomon-Simmons, said the massacre was one of “the most heinous acts of racial terrorism committed in the United States by those in power against Black people since slavery. White elected officials and business leaders failed to repair the injuries they caused and engaged in conduct to deepen the injury and block repair.”

And yet, in July 2023, Tulsa County District Judge Caroline Wall dismissed the lawsuit with prejudice, meaning that it could not be retried.

Last month, Solomon-Simmons filed an appeal on behalf of the victims before the Oklahoma State Supreme Court. The case is pending.

Frequently, during conversation or one of the many public appearances Van Ellis made on behalf of the Tulsa Race Massacre victims, he remained positive about the fight for justice. He often invoked one phrase. “We are one,” he said, raising a finger in the air to dramatize his point. Many interpreted his familiar refrain as firmly believing that humanity and righteousness would eventually prevail.

After Van Ellis’s passing, his grandnephew, Ike Howard, said he carried that optimism with him to the end. “He still believed the state would do the right thing,” Howard said. “He died waiting on justice.”

An engaged public figure

As a national figure, Van Ellis stepped easily into public appearances and appeared to relish the limelight. At one point he was rolling through the streets of Accra, Ghana in a carriage bedecked with flowers. At another, he was joking with reporters at a Tulsa press conference. More recently, Van Ellis appeared at an event at The Schomburg Center For Research in Black Culture in Harlem, New York, alongside his sister Viola Fletcher, promoting her book “Don’t Let Them Bury My Story.” His 2021 testimony to congress serves as the book’s forward.

In the summer of 2022, Van Ellis and the two other survivors met in the offices of The Oklahoma Eagle in the Greenwood District with New York philanthropists Ed and Lisa Mitzen and several others, including the actress Vanessa Williams. The Mitzens had given $1 million to the three race massacre survivors in May 2022. They returned for a visit to Tulsa in December 2022.

The Mitzens’ entourage included former Miss America, singer, actress, and fashion designer Vanessa Williams; Tony Award-winning actress, director and producer Tamara Tunie, who is most widely known for her role on “Law & Order: Special Victims Unit;” and other celebrities.

During the meeting, Van Ellis lit up when he saw Williams. He shared that he attended an event a decade or so earlier featuring her. He asked for her autograph. Williams embraced the opportunity and asked Hughes if he had a pen. Unfortunately, he could not obtain the autograph at that time.

While at The Oklahoma Eagle, Hughes said although he could not get her autograph years ago, he would not allow this opportunity to pass.

When Williams learned about Hughes’ missed quest for her autograph, she embraced the moment. She signed a copy of The Oklahoma Eagle that featured Hughes and other survivors. Van Ellis expressed thanks and a thrill that made for a priceless episode.

The sojourn to Ghana

In August 2021, Van Ellis and his sister Viola Fletcher were invited to a whirlwind trip to Ghana. Van Ellis was made a chief and presented by the Palace of Eze Ndi Igbo Ghana with the new name of “Ike Ohe Ndi Igbo,” meaning “Strength of the Igbo.” Van Ellis also received the name “Nii Lante,” from the Osu Traditional Council, meaning “Loves helping other people because he has a kind heart.”

During the visit, Ghana’s president, Nana Akufo-Addo, recognized the resilience of Fletcher and Ellis, who survived the Tulsa Race Massacre, one of the worst incidents of racial terror committed against Black people in America.

“They lived to tell the story,” Akufo-Addo told reporters.

Later, Van Ellis said in an interview, “I let the world know that we are one. I let the world know that nobody can stop us. They tried to burn, kill, smoke, and drag us. We are still here.”

After returning to the U.S., Ellis described the trip as “going back home.” In a meeting with reporters, he said, “The peace and the quiet. It was overwhelming. I felt like a king. It made me so proud to be there.”

Remembrances

Van Ellis closely touched the lives of everyone who came into his orbit.

“I’ll remember each time Uncle Redd’s passionate voice reached hearts and minds in courtrooms, halls of Congress, and interviews,” said Solomon Simmons, the Tulsa attorney who worked closely with Van Ellis. “Most of all, I’ll forever cherish the time we spent together behind the scenes. He was much more than a client. He was a partner in the quest for justice and reparations. He was a source of inspiration and strength during times of doubt and despair. He was family, and I loved him. His presence will be sorely missed.”

Goodwin came to know Van Ellis well during her years of advocating for him and other race massacre survivors and descendants.

“He had a don’t quit spirit,” she recalled in an interview. “He was always super positive. When we met with him a couple of days ago, he told us to keep up the fight.”

The Mitzens also remember Van Ellis fondly. “The term “American hero” is often tossed around loosely,” he said in an interview. “However, for Mr. Van Ellis, it is perfect. He was bombed as a child in Greenwood, and then risked his life to fight in World War II, being bombed once again. He was a giant. Lisa and I loved the times we spent with Uncle Redd. His huge smile would light up the room. We feel so blessed to have gotten to know him these past few years.”