The survivors, descendants, and communities of Tulsa, Oklahoma that continue to struggle in the wake of the state-sanctioned, institutional and societal racism that culminated in the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, followed by more than 100 years of legislative cowardice intended to protect the interests of those who benefited from the deaths of the innocent, will find no immediate respite in the halls of Tulsa district courts, revealed by Tulsa County Judge Caroline Wall’s final ruling late Friday, Jul.7.

We learned, on Aug. 3, after reading Wall’s order regarding Randle v. City of Tulsa, that although survivors have legal standing to pursue injury claims, Tulsa communities must rely upon state legislators for ‘remedy’. The same republican-led, politically conservative cast of legislators that legalized the suppression of teaching a comprehensive national history and the protection of public-school students’ comfort when discussing racial bias, must now be trusted to right their wrongs.

Simply stated, justice for Tulsa communities will not be achieved via Oklahoma’s courts.

“Separation of powers”, the Oklahoma court’s safe word, a state constitutional statute akin to “well, I don’t believe that our history of violence against Black Tulsans was that bad,” affords descendants of the Race Massacre and Tulsa communities today, nothing more than shrugged shoulders and stoic countenances from Oklahoma jurists. How such a well-forged shield against reasonable calls for accountability impacted the efforts of the Justice for Greenwood legal team was a question finally answered, and no sign of relief remains visible for the descendants of the Historic Greenwood District.

THE CONTEXT

“With joy, we once did greet you, but with sadness, we depart.”

— 1921 Class Poem Excerpt, Booker T. Washington High School, Tulsa, Oklahoma

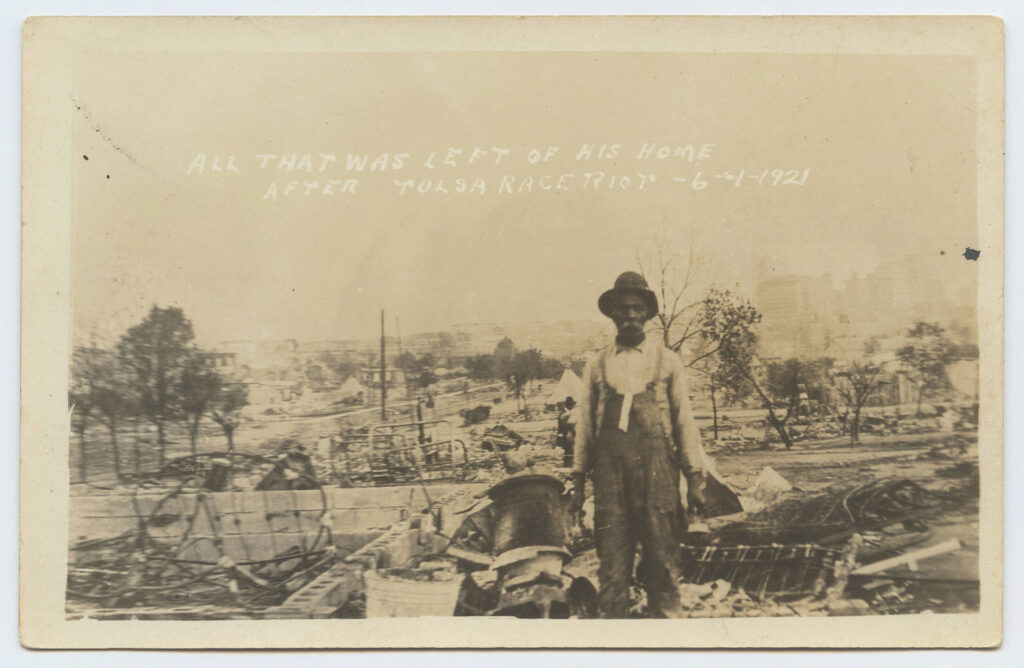

The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre descendants’ claims reveal the deeply rooted depravity of the City of Tulsa’s governing, law enforcement, state agency and neighboring white residents’ long-survived hatred of the Historic Greenwood District’s Black citizens.

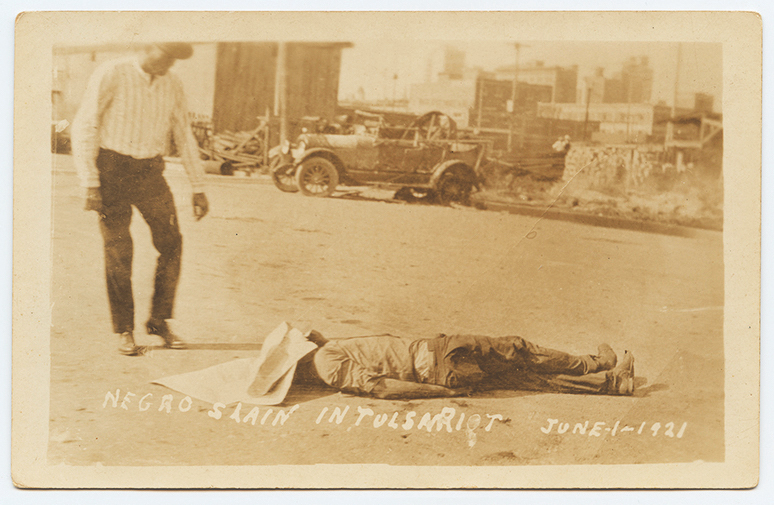

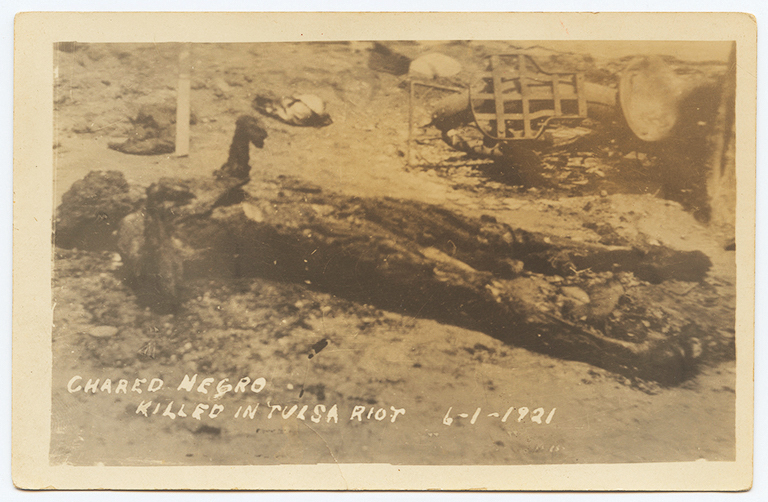

Known, are the facts that are accurately represented as the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, a days-long siege against the Black residents of the District, leaving behind the slain bodies of as many as 300 innocent men, women and children upon the open ground, beneath the summer sun.

By days end, on June 1, upwards of 10,000 Greenwood residents were reft of their homes, businesses, churches and livelihoods of what once comprised the nation’s most prominent and successful Black community. White Tulsans, in the wake of these atrocities, left fires that burned throughout the night, filling the darkened sky with the ashes of those who once regarded the streets of Greenwood safe.

With only 18 graduates, Tulsa’s renowned Booker T. Washington High School’s 1921 graduating class would mark the moment and their accomplishments as the same point in time when their neighbors, friends and family members potentially fled their homes, only to be murdered upon entering the street.

As the siege began, many Black Tulsans were forced to risk their lives in protection of older family members. Carrie Kinlaw, a woman who lived near the Section Line, ran toward the fighting in order to help her siblings retrieve their “invalid” mother. The “rain of bullets,” described by Kinlaw, were fired by approximately six squads of rioters who overtook the family. Kinlaw recalled, with great clarity, that her eventual captors with not merely adults, but children “from about 10 years upward, all armed.”

“Is the whole world on fire?” asked a young playmate of eight-year-old Kinney Booker, who was fleeing with his family from their home on North Frank fort.

The ongoing horrors appeared without limit. “One Negro was dragged behind an automobile, with a rope around his neck, through the business district,” reported the Tulsa World in its “Second Extra” edition on the morning of June 1.

Many white Tulsans met the prospect of murdering innocent Black residents without pause, as detailed by Guy Ashby, a young white employee at Cooper’s Grocery. The fourteenth street proprietor informed Ashby, after arriving for work, that “there would be no work that day, declaring it ‘Nigger Day,’ and that he “was going hunting niggers.”

NAACP civil rights investigator Walter Francis White, who traveled to Tulsa after the riot, recounted in an article published by The Nation magazine:

One story was told to me by an eyewitness of five colored men trapped in a burning house. Four burned to death. A fifth attempted to flee, was shot to death as he emerged from the burning structure, and his body was thrown back into the flames. – The Eruption of Tulsa, White, F., The Nation, 1921

State agency officials actively “participated in the mass arrests of all or nearly all of Greenwood’s residents, removed them to other parts of the city, and detained them in holding centers”, according to the commission’s report. Forcibly detained, thousands of Black Tulsans would only gain their release “upon the application of a white person, and then only if that white person agreed to accept responsibility for that detainee’s subsequent behavior.”

Further detailed in the Final Report of Findings and Recommendations of the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Commission, civil officials, deputized citizens, public officials, units of the Oklahoma National Guard, agents of the government and private citizens, all white, committed “overt acts” of violence against Black Tulsans. To date, more than 100 years later, “Not one of these criminal acts was then or ever has been prosecuted or punished by government at any level, municipal, county, state, or federal.

Originating in 1997 with Oklahoma House Joint Resolution No. 1035, and twice amended, the Commission was charged with undertaking a study to develop a historical record of the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot. The commission’s final report reflected insights gathered from testimony, extensive research, established records and included contextual summaries by Drs. John Hope Franklin and Scott Ellsworth.

The later authors’ work, in part, included an account of the significant destruction of Greenwood’s commercial district. “The Stradford Hotel, a modern fifty-four room brick establishment which housed a drug store, barber shop, restaurant and banquet hall, had been burned to the ground. So had the Gurley Hotel, the Red Wing Hotel, and the Midway Hotel. Literally dozens of family-run businesses—from cafes and mom-and-pop grocery stores to the Dreamland Theater, the Y.M.C.A. Cleaners, the East End Feed Store, and Osborne Monroe’s roller-skating rink — had also gone up in flames, taking with them the livelihoods, and in many cases the life savings, of literally hundreds of people. The offices of two newspapers — the Tulsa Star and the Oklahoma Sun — had also been destroyed, as were the offices of more than a dozen doctors, dentists, lawyers, realtors, and other professionals. A United States Post Office sub-station was burned, as was the all-black Frissell Memorial Hospital. The brand-new Booker T. Washington High School building escaped the torches of the rioters, but Dunbar Elementary School did not. Neither did more than a half-dozen African American churches, including the newly constructed Mount Zion Baptist Church, an impressive brick tabernacle which had been dedicated only seven weeks earlier.”

Tulsa’s culpability has long been a subject of consistently nuanced truths, its sharp edges blunted, faces made indistinguishable, records ‘lost’, official capacities now undeterminable and voices muted… whitewashed.

The ‘least biased’ accounts, noted within the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, reveal a chronology of events and culpability that fully align with the context articulated by Damario Solomon-Simmons, the Tulsa-based attorney representing Lessie Benningfield Randle, Viola Fletcher, and Hughes Van Ellis, Sr., survivors of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

The 1926 opinion of the Oklahoma Supreme Court, written by Commissioner Ray, in Redfearn v. American Central Insurance Company, provided a foundational account of the events that transpired prior to siege upon Black Tulsans.

William Redfearn, a white man who owned and subsequently lost two buildings in Greenwood during The Massacre, the Dixie Theatre and the Red Wing Hotel, sued the American Central Insurance Company after his claim was rejected, citing a riot exclusion clause in the policies.

The court’s opinion, after two years of litigation, established the following record:

The deputy marshal in the case before us had no more authority to set the house on fire than the sheriff in the case cited… The loss of the house was not due, directly or indirectly, to the riot carried on by the men within the house. It was due directly to the wrongful act of the marshal in setting fire to the house without authority.

While the evidence shows that a great number of men engaged in arresting the negroes found in the negro section wore police badges, or badges indicating they were deputy sheriffs, and in some instances were dressed in soldier’s clothes and represented to the negroes that they were soldiers, there is no evidence that any negro ever resisted arrest, or that any fire was started in order to make such arrest.

Redfearn v. American Central Ins. Co., 116 Okla. 137, 139 (Okla. 1926)

Commissioner Ray, yielding to a pro-police bias, concluded that although the white men who participated in the act of arson against Redfearn’s property were “wearing police badges or sheriff’s badges” there was no evidence that they were acting in an official capacity.

The court’s opinion, however, was contradicted by the account of Major General Charles F. Barrett, of the Oklahoma National Guard during the riot, who authored Oklahoma After Fifty Years, recounting that the police chief deputized perhaps 500 men to help put down the riot.

He did not realize that in a race war a large part if not a majority, of those special deputies were imbued with the same spirit of destruction that animated the mob.

They became as deputies the most dangerous part of the mob and after the arrival of the adjutant general and the declaration of martial law the first arrests ordered were those of special officers who had hindered the fire men in their abortive efforts to put out the incendiary fires that many of these special officers were accused of setting.

Such leaps beyond base reasoning and desperate parsing are now far too common amongst Oklahoma officials. In early July, former high school history teacher and current Oklahoma Superintendent of Public Instruction, Ryan Walters, attempted the same poorly executed mental gymnastics. Walters, a staunch opponent of fully contextualized public school history curriculum, attempted to divorce race from The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

THE CASE

No children have we to lament, no wives to wail our fall; The traitor’s and the spoiler’s hand have reft our hearths of all.

— Aytoun, W. E., The Island Of The Scots

In the fall of 2020, Randle, Fletcher, Van Ellis, Sr. and The Massacre descendants would commit to achieving the accountability long avoided by the City of Tulsa for almost a century.

Randle v. City of Tulsa would represent the voices of The Massacre survivors, descendants, Black Tulsans, Black Americans and all advocates of social justice.

The lawsuit, with significant detail, framed the plaintiffs’ core arguments, that the survivors and descendants of The Massacre are the ensouled human foundation upon which the City of Tulsa liberated white fear, denied just accountability, failed to invest in restorative measures and enriched itself via tourism and funding received by appropriating, then misrepresenting, its sordid history, for which plaintiffs have “reaped no significant direct benefits.”

The statutory means employed and legal precedents cited were well-considered. Solomon-Simmons structured the plaintiff’s claims as a demand for remedy of the “public nuisance” created by the defendants and a recovery for “unjust enrichment” for the defendants’ exploitation of The Massacre.

Solomon-Simmons argued that the Massacre “had and continues to have a severe impact on the comfort, repose, health and safety” of the Greenwood neighborhood and Greenwood community of Tulsa.

Personal recounts and formal testimonies, a fraction of which were previously highlighted, reflect the economic and psychological torment endured by Black Tulsans in 1921.The loss of family, homes, businesses and community continue to strain the hearts and minds of the once prosperous Black Wall Street.

The years-long litigation was marked by a series of motions advanced by defendants to dismiss the case on the basis of ‘legal standing’, challenges to claims of tribal bloodlines, and withdrawals of counsel. By Aug. 2022, Tulsa County Judge Caroline Wall would issue an order that served as a turning point for the case.

During the post-ruling press conference, Aug. 4, Solomon-Simmons’ optimism was unwavering as he responded to Wall’s ruling.

The mid-day video conference was framed by Solomon-Simmons’ expression of gratitude for the support of the Greenwood community through prayer rallies, townhall meetings, donations, and inspiring words. Tulsans, and many Americans, remained well-invested in the outcome of a case that represented one of country’s longest standing pursuits for legal redress.

Joined by Justice for Greenwood legal team members Michael Swartz, Kymberli Heckenkemper, Randall Adams, Ekenedilichukwu “Keni” Ukabiala, and Eric J. Miller, Solomon-Simmons recounted the legal journey thus far, and provided some insight about the pathway forward for the survivors and descendants.

Judge Wall’s ruling was a formal response to the defendant’s latest motion to dismiss claims made by an historic Tulsa church, a member-based association and 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre survivors and descendants.

The court’s order affirmed the legal standing of the survivors of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, Lessie Benningfield Randle, Viola Fletcher and Hugh Van Ellis, Sr. in pursuit of their public nuisance claim, however, Wall established a clear delineation of claims regarding the “ongoing” nuisance for events subsequent to the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. The distinction was significant, as Wall dismissed the specific claim with prejudice, noting that “these claims request relief that violates the separation of powers provided by the Constitution of the State of Oklahoma.” The narrowed scope of the lawsuit was then limited to claims for remedy for past events.

The “landmark ruling”, as described by Swartz, was not the preferred outcome of most plaintiffs, as 8 of 11 claims were dismissed with prejudice.

Historic Vernon A.M.E. Church, Inc., a faith-home for Black Tulsans for more than one-hundred years, alleged property damage and the loss of prominent members, including its pastor C.R. Tucker, according to the initial brief filed. The City of Tulsa, and defendants, successfully challenged Historic Vernon A.M.E. Church, Inc’s standing by noting that the entity was not a legally recognized institution as of The Massacre, thus unincorporated, evidenced by the institution’s Incorporation Documents, referenced as exhibit 1. Prior to 2019, Wall recounted, the property owner of the church was also an unincorporated entity in 1962. A technical concern, certainly, but it was sufficient enough for Wall to reject the church’s standing.

The legal standing of other Defendant-Plaintiffs, Laurel Stradford, Ellouise Cochrane-Price, Tedra Williams, Don M. Adams, Don W. Adams, Stephen Williams, and The Tulsa African Ancestral Society was similarly challenged and denied.

In retrospect, Wall’s position regarding the “separation of powers,” appears to have foreshadowed her final ruling on Jul. 7.

THE RULING

A ruling offering fewer words than the number of Black Tulsans killed in 1921.

Survivors and descendants of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, residents of the City of Tulsa and all who followed the century-long fight for accountability, were forced to speculate about the justification for Tulsa County Judge Caroline Wall’s final ruling of Randle v. City of Tulsa late Friday, Jul. 7.

Wall’s ruling, with fewer than one hundred words, offered none of the context appropriate for the matter recently considered by the court, reflected by sentiments shared by local Tulsa residents since the ruling.

Tulsans must now parse Wall’s references to a “review of the record” and “the defendants’ briefs filed of record” in search of an explanation for the single paragraph ruling.

‘The record’, Tulsans must assume, are the City of Tulsa and defendant’s motions to dismiss Randle v. City of Tulsa, most specifically, the basis for which dismissal was ultimately accomplished.

Oklahoma State Courts Network (OSCN) reveals an exhaustive archive of no less than fifty attempts to invalidate the legal standing of and complaints by plaintiffs in Randle v. City of Tulsa. The Aug. 4 ruling, however, addressed all challenges against plaintiffs Randle, Fletcher and Van Ellis, Sr., with The Massacre survivors meeting the ‘statutory criteria to withstand a motion to dismiss’, only as it applied to the public nuisance claim.

The earlier ruling was unfortunately contingent upon Solomon-Simmons’ response to ‘cure’ his petition, a leave granted to clearly articulate a legally ‘cognizable abatement remedy the court’ could act upon, without a conflict with the ‘separation of powers’ statute in the state of Oklahoma constitution.

The substance of Wall’s argument rest shallow. The Tulsa judge sat in-witness of well-stated historic atrocities and the sheer destruction caused, yet offered a narrow course for remedy, upon which no substantive resolution could be granted.

Yes, the raising of a community and the violent death of innocent men, women and children did occur.

Yes, the decades that followed The Massacre were fraught with public acts of oppression by the City of Tulsa.

Yes, the Historic Greenwood District was denied the right to peacefully exist and thrive.

But today, the injury sustained, and the lasting effect of such evil, will not be resolved.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you move on, I was hoping you would consider taking the step of supporting The Oklahoma Eagle’s journalism.

From the various media outlets in our market, to a small number of billionaire owners and private equity firms have a powerful hold on so much of the information that reaches the public about what’s happening in the world. The Eagle strives to be different. We have no billionaire owner or shareholders to consider. Our journalism is produced to serve the public interest – not profit motives.

And we avoid the trap that befalls much U.S. media – the tendency, born of a desire to please all sides, to engage in false equivalence in the name of neutrality. While fairness guides everything we do, we know there is a right and a wrong position in the fight against racism and injustices. When we report on issues like the mental health crisis in the Black community, the ongoing issues with public education and the political discord and troubling legislation being enacted at the Oklahoma statehouse, we’re not afraid either to name or hold those individuals responsible for problems that work against improving the lives of Black people.

Around this nation, our readers can access the Eagle’s paywall-free journalism. Our readers keep us independent, beholden to no outside influence and accessible to everyone – whether they can afford to pay for news, or not.

If you can, please consider supporting the Eagle today. Thank you.

James O. Goodwin, publisher