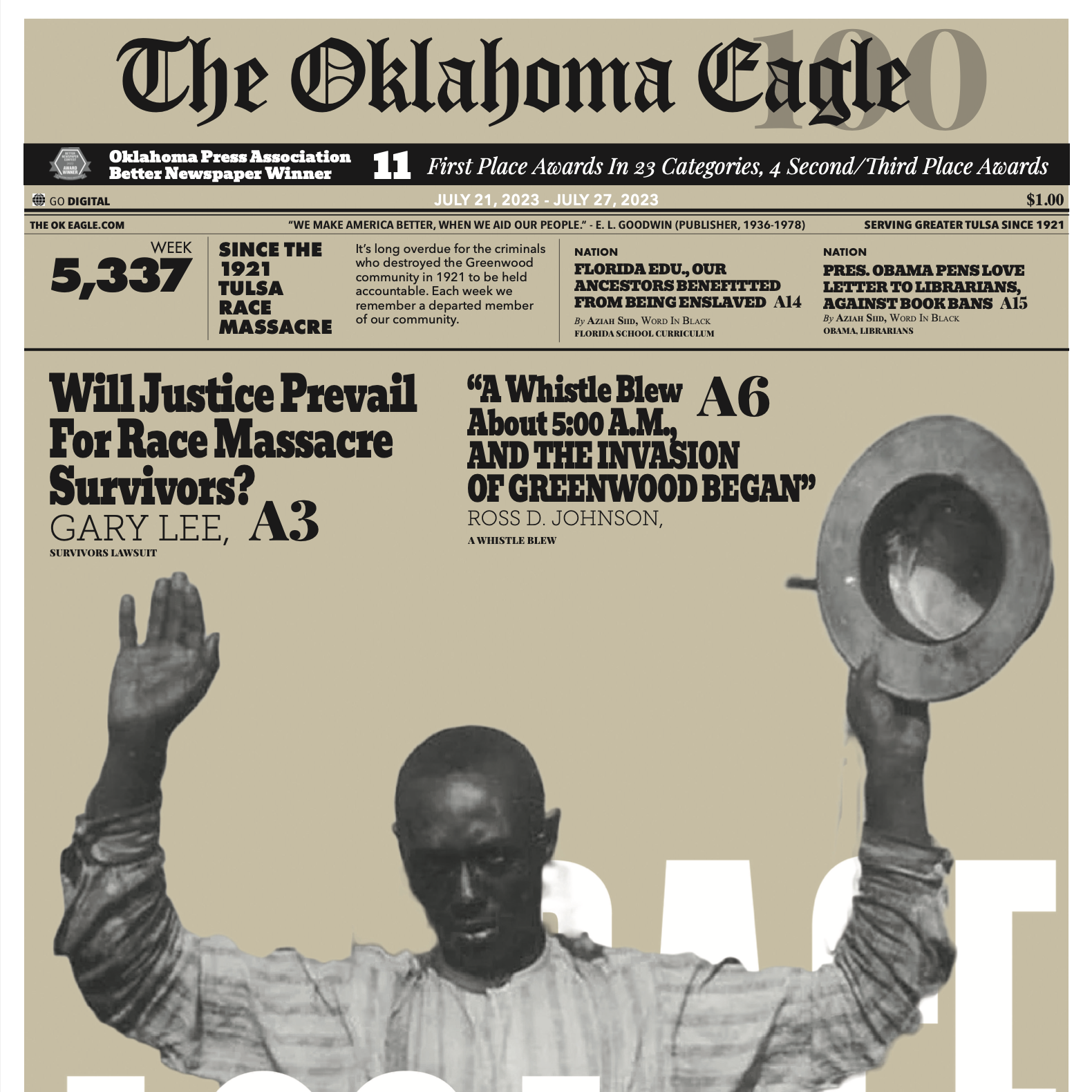

OPINION

Ross D. Johnson

Illustration, The Oklahoma Eagle & Adobe Images

Oklahoma, whose sovereignty was born of the deaths of indigenous peoples, wasted little time protecting the interests of white residents upon its founding in 1907.

The state’s laws enforced legal segregation in the early 1900s, ensuring explicit social, education, civic and public accommodations boundaries between white and Black Oklahomans.

In the decades that followed, Arkansas, Oklahoma’s eastern border Bible Belt neighbor, employed the same measures of legalized survival for whites.

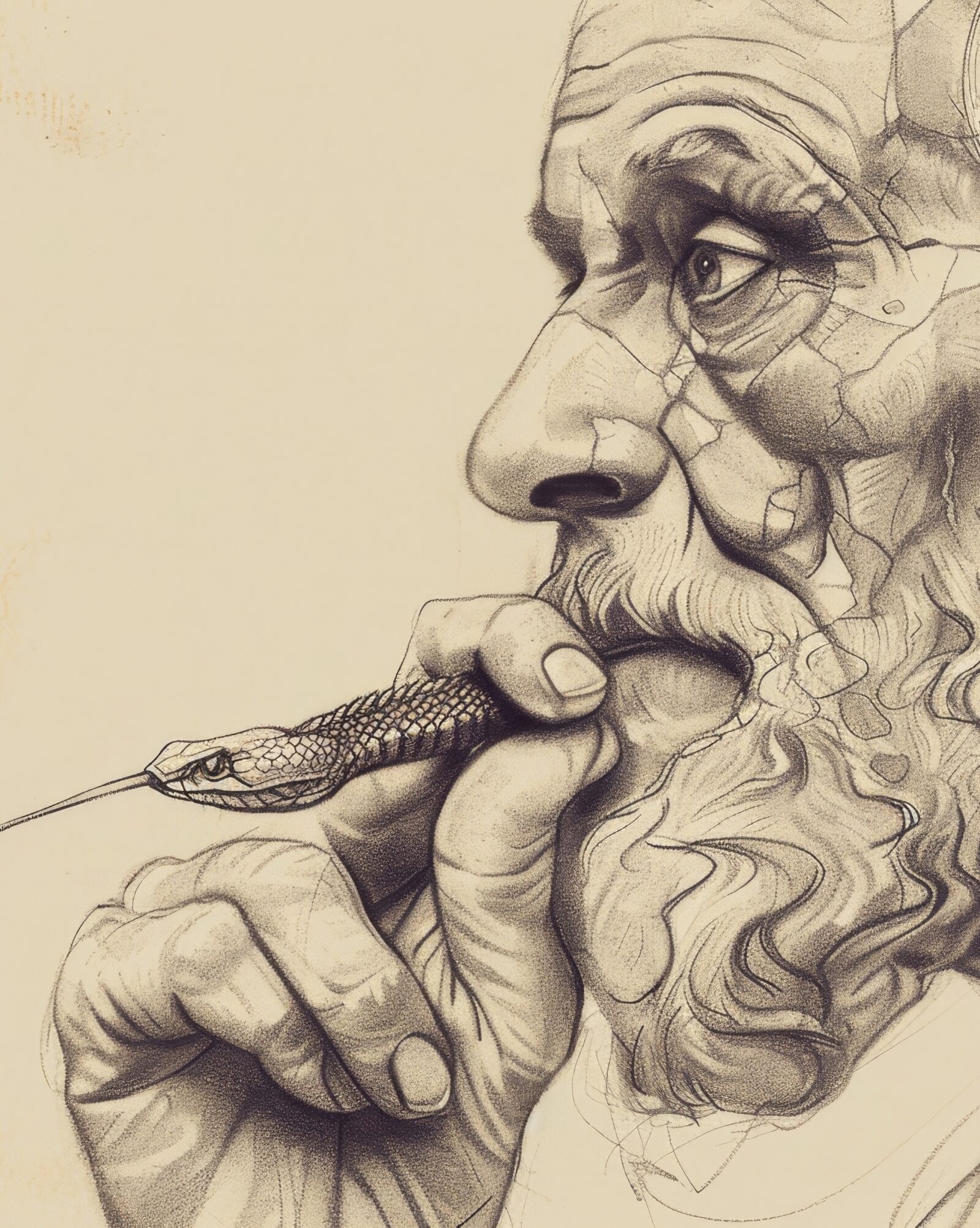

The longstanding populism of white self-interests stood in sharp relief against residents’ claims of Judeo-Christian faith. Those interests in many ways mirrored the 19th century doctrine of Manifest Destiny, a perceived divine call to conquer at any cost.

The populists’ embrace of state sanctioned hatred against – and the oppression – of Black and Indigenous peoples was of a greater moral priority than the core tenets of their professed faith.

God’s place, one may objectively determine, of most early 20th century Oklahoma legislators, was to guide and protect the hand that inflicted harm, as the back upon which it fell was not worthy of His grace.

Of the 21st century, one may objectively determine that Oklahoma courts and legislators are convicted to guard against demands of accountability for sins that define the state’s history and moral character.

From Arkansas to Oklahoma

The saga of Orval Eugene Faubus is relevant for these times. Faubus was a relatively new face in politics in 1936. The Madison County, Arkansas native, from a modestly populated (approx. 11k) hill community in northwest Arkansas’s Ozark Mountains, entered politics contesting a seat for the Arkansas House of Representatives. Although unsuccessful in his bid for a House seat, Faubus later ran for and was elected to the position of circuit clerk and recorder of Madison County in 1938.

The small-town son of liberal parents – John Samuel, a self-educated farmer, and Addie Joslin – Faubus was raised in a household that viewed capitalism as an obstacle to their American dream.

So fervent was John Samuel’s socialist beliefs, that he urged his son to attend Commonwealth College, near Mena, Arkansas. The institution, founded in 1923, aimed to recruit and train people to take the lead in social and economic reform. Internal conflicts amongst founders would lead to the institution being re-established in Mena in 1925).

Later, as an Army intelligence officer, serving as a major in the 320th Infantry Regiment, Faubus completed his duty to his country and returned home to labor as the Huntsville Postmaster.

Faubus, grounded in the pragmatism of the era that was reflected in U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, was well-aligned with the Democrat Party.

Viewed largely as a longshot, a relatively unknown figure of Arkansas polity, Faubus faced considerable challenges from political opponents as he entered the race for governor in 1954.

“Forward with Faubus’, the ’54 campaign slogan, was a grassroots appeal targeting the ‘working man’, an electorate whose voices competed with the vocal demands of civil rights activists.

At the height of the campaign the U.S. Supreme Court issued its historic Brown v. Board of Education decision, declaring unconstitutional all laws establishing segregated schools. Marking the end of the ‘separate but equal’ precedent set by the Court nearly 60 years earlier in Plessy v. Ferguson, the ruling set in motion the integration of public schools, against significant resistance.

By the 1950s, Arkansas was home to more than 426k Black Americans, representing 29 percent of the state’s population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Experiencing historic declines of aggregate population in rural areas, increased population density in urban areas due to the lack of agricultural resources relative to farmers (The Great Migration) and the progressive demands of the civil rights era, race would become a central focus of Faubus’s campaign.

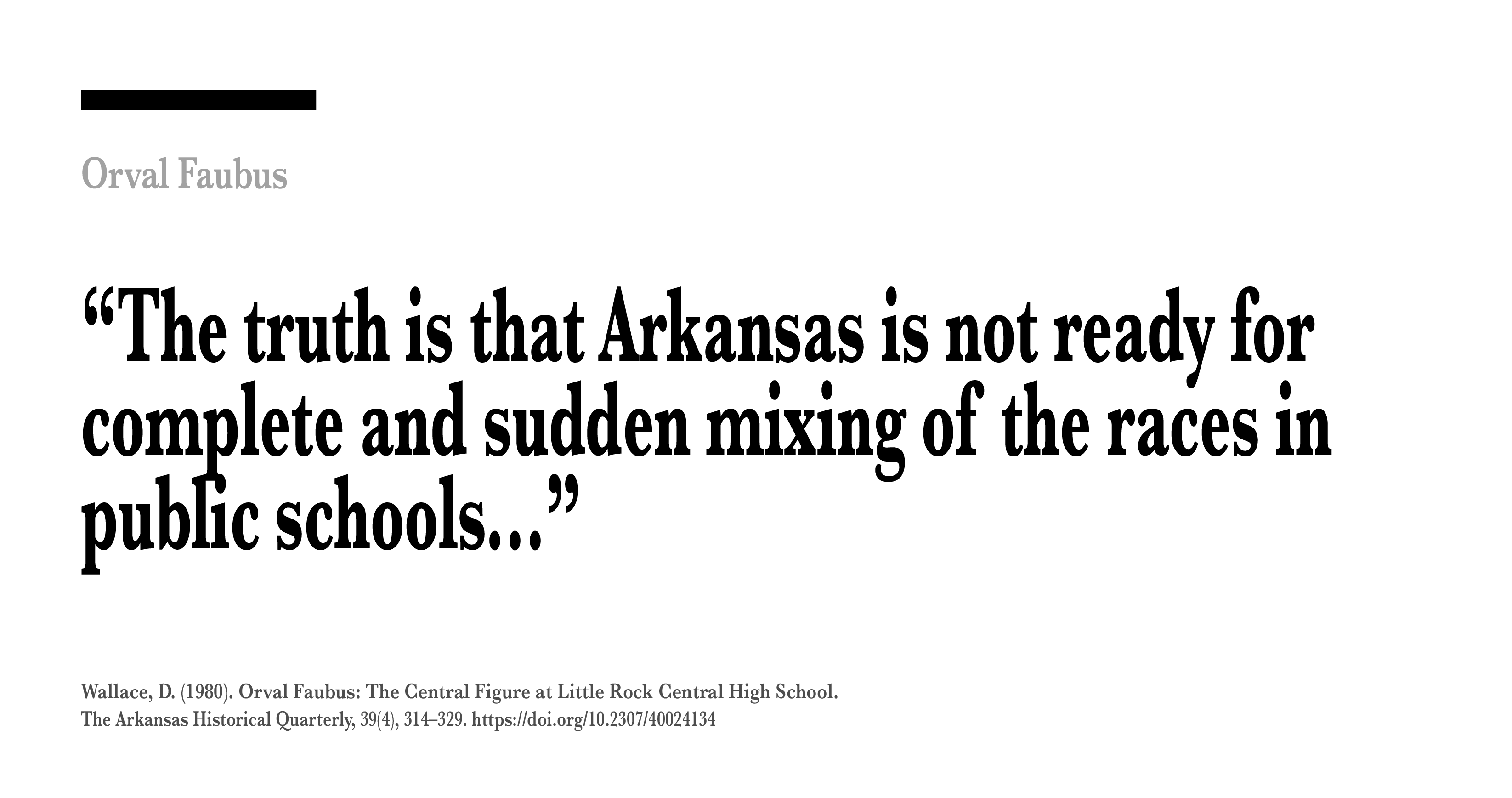

Seeking to garner the interests of Arkansans early in the primary, and rebuff accusations of being sympathetic to socialists’, Faubus held that race, more specifically desegregation, was the “number one issue” in the gubernatorial campaign.

“The truth is that Arkansas is not ready for complete and sudden mixing of the races in public schools,” Faubus opined in reporting by the Little Rock Arkansas Gazette on June 6, 1954.

“Gaining access to white schools,” Faubus noted, was not a matter “important to Negroes.”

The son of Madison County later claimed that the “problem of Desegregation” was a matter for state authorities to address.

The first-term governor’s expressed regard for ‘law and order’ was rooted in a faith that local government, ordinances, statutes and authority best represented the interests of Arkansas.

Faubus, having discovered the value of populist hatred, would serve as Governor of Arkansas for six two-year terms, highlighted by a rejection of federal authority and profound racial animus during his second term in 1957.

The convenient, and inarguably hypocritical, shift from pragmatism to a populism grounded by nationalism and protected by claims of faith was not a first for politicians in Arkansas, or any state of the union.

The assumed mantle of “not our problem to solve”

Black Oklahomans of Tulsa, the state’s second largest city, would soon embody the full spirit of self-reliance in the district of Greenwood. Black Wall Street, the state’s epicenter of Black excellence, would become an Eden of commerce, education, entrepreneurship and faith.

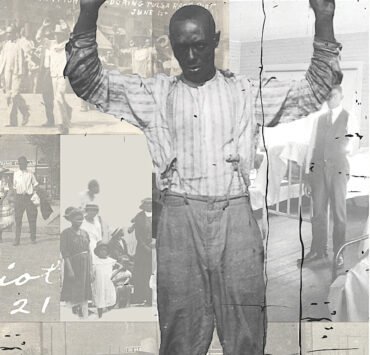

Black Wall Street’s razing, and the broad-scale murder of its Black residents by white mobs, city and state authorities in 1921, has scarred a community and people so deeply that wounds remain present today. The destruction of an economic base that fueled community growth, entrepreneurial opportunities, and strengthened public education still mars the state’s history.

“Is the whole world on fire?” asked a young playmate of eight-year-old Kinney Booker, who was fleeing with his family from their home on North Frank fort, an account represented in the Tulsa Race Riot A Report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 and The Oklahoma Eagle reporting.

Walter F. White, author of The Eruption of Tulsa (1921), an account of the Tulsa Massacre published by The Nation, recalled “One story was told to me by an eyewitness of five colored men trapped in a burning house. Four burned to death. A fifth attempted to flee, was shot to death as he emerged from the burning structure, and his body was thrown back into the flames.”

Oklahoma’s courts and legislature, like Gov. Faubus and Arkansas legislators of the mid-century, appeared to work in concert after the historic act of domestic terrorism, shielding the state from accountability.

As Faubus served as a vanguard against justice during the 1950’s, so too have Oklahoma’s courts and legislature, seventy years later.

“Unlike most cases that come before this Court, the tragedy that forms the basis of the present appeal is acknowledged and memorialized, at least in part, in Oklahoma law,” wrote Dustin P. Rowe, Vice-Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the State of Oklahoma, in the court’s opinion announced on Jun. 12.

Rowe, representing the highest court of the state of Oklahoma, acknowledged the import of the state’s sin, the scope of Black men, women and children murdered during the siege against the Greenwood District community, and the mass detention that followed.

Rowe further highlighted “The destruction of more than 1,200 homes, schools, churches, and businesses”, the culpability of “local officials” who “engaged in actions that exacerbated the harm destruction”, and the attempts to “block the rebuilding of the Greenwood community by amending the Tulsa building code’, yet ruled that the relief sought by Lessie Benningfield Randle, Viola Fletcher, and Hughes Van Ellis was “not possible.”

The contention on appeal was the public nuisance claim rejected by Judge Caroline Wall, of the District Court of Tulsa County, on July 7, 2023.

A “public nuisance”, as defined by Okla. Stat. tit. 50 § 2, and represented in Rowe’s ruling, “exists when the offending party unlawfully does an act, or omits to perform a duty, which act or omission either:

- First. Annoys, injures or endangers the comfort, repose, health, or safety of others; or

- Second. Offends decency; or

- Third. Unlawfully interferes with, obstructs or tends to obstruct, or renders dangerous for passage, any lake or navigable river, stream, canal or basin, or any public park, square, street or highway; or

- Fourth. In any way renders other persons insecure in life, or in the use of property, provided, this section shall not apply to preexisting agricultural activities.

Of the criteria noted, the first, second and fourth are clearly relevant to the survivors’ claims. The state’s highest court, in what appears to be a stark contradiction to established jurisprudence, has determined that the “lingering consequences over one-hundred years later, standing alone, do not constitute a public nuisance, as that term has been construed by this Court.”

The correlations between the court’s stated criteria for a public nuisance and the injury to the Greenwood District of Tulsa are neither vague nor require an investigative effort to unearth comprehensive truths, as the facts are well documented and acknowledged by the court.

Did the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre yield longstanding injury and endangerment to the comfort, repose, health and safety of its residents as a result of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre? Yes.

Did the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre “offend the decency”, generally regarded as behavior that is good, moral, and acceptable, of the state of Oklahoma? Yes.

Did the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre “render other persons insecure in life”? Yes.

The abatement of such an obvious “public nuisance”, compounded during the last one-hundred and three years, should be, by any moral standard, a question of relief, compensatory and punitive damages.

Relief, inferred by Rowe’s opinion and the court’s majority, is a narrowly defined consideration of remedy, absent accountability.

The Vice-Chief Justice, at least perceived by many Oklahomans, regarded the matter of accountability as ”not important to Negroes”, in the same manner as Faubus.

Any belief to the contrary would require Oklahomans to ignore the explicitly met criteria for the determination of a public nuisance.

The Oklahoma Supreme Court’s “acknowledgement” of damage rest hollow, a statement carried upon wasted breath, or more precisely, a nod towards a willingness to admit profound immorality and injustice while being committed to not acting in service of justice.

Lessie Benningfield Randle, Viola Fletcher, and Hughes Van Ellis (Muriel Watson, the Personal Representative for the Van Ellis, who passed early this year.) sought both relief and accountability, matters related to the ongoing injuries against Black Tulsans, a demand for being made whole and the wages of the city’s sins. In simple terms, triage, remedy and punishment.

Rowe narrowly focused on remedy, and even within the applied limited scope, ignored the criteria by which his ruling should have been guided.

The dilemma of morality

The import of the court’s decision is clear, that the state of Oklahoma has formally indemnified itself, at least within the view of the state’s judiciary.

Apparent to many residents of the state, is that any course which requires Oklahomans to seek remedy by the legislature must rely upon the frail thread binding moral obligation and populism.

Oklahoma’s populism, as it relates to race, is similar to that of mid 20th century Arkansas. The majority republican legislature may be characterized, without malice, as a governing body committed to an historic narrative of blameless historic atrocities, a blissful ignorance regarding the impact of such atrocities, and the long-standing mass entombment of Black Tulsans murdered more than one-hundred years ago.

Such populism, as embraced by Faubus, regards the plight of the majority as the only priority, a moral imperative. Support for policies that satisfy the majority’s needs, calm irrational fears, and protect false historic narratives is garnered by framing the agenda as a moral pursuit. The endeavor, we are told, evolves to representing the best interest of all people, yet that sentiment isn’t truly embraced by those who must severe relationships with their own history and facts.

The state’s Grand Old Party dominated legislature has made good on its role in supporting Oklahoma populism, leaning upon institutions that must now statutorily guard against white students’ feelings of guilt, as it relates to the violence experienced by Black Tulsans historically.

In 2021 the Oklahoma legislature passed HB 1775, prohibiting school course instruction that engenders any personal feeling of “discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race or sex.” That the purpose of education is not to cast blame, lift one greater than another, conceal facts or elevate select truths, is an obvious point of contention for the legislature is troubling.

“Education without morals is like a ship without a compass, merely wandering nowhere. It is not enough to have the power of concentration, but we must have worthy objectives upon which to concentrate. It is not enough to know truth, but we must love truth and sacrifice for it.” – Martin Luther King, Jr., “The Purpose of Education”, Maroon Tiger, Morehouse College, 1947

Lessie Benningfield Randle, Viola Fletcher, Hughes Van Ellis, the living descendants of Black Tulsans felled in 1921, and surrounding communities awaken, work, love, discover new joy, reach, grasp, sit, and rest each day against a backdrop of a century old trauma that has shaped their everyday experiences. Where homes once stood, with families that prayed together, in neighborhoods that worshiped together, are blocks of sunken foundations, economic decline and dreams surrendered.

Survivors, and their descendants, are men and women who may rightfully be regarded as griots, within whom stories possess great weight and import. Few introductions may be shared without a recitation of lineage, history and relationships.

For Black Tulsans, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre was neither a tipping point of hatred, a moment of populists’ hatred, nor an hours-long siege against the innocent. What transpired on May 31, 1921 was the sudden and violent theft of life, followed by more than a century of state officials keeping a weather eye on attempts to salvage what remains, offering nothing meaningful.

Remedy, as represented by the Supreme Court of the State of Oklahoma, is a misnomer, or most precisely, a fallacy proselytized by those who attend church service on Sundays then drive by the mass graves of murdered Black bodies buried in Oaklawn Cemetery, without a care or concern.

The embrace of true remedy, or faith that state officials were capable of such, would require that Black Tulsans ignore what has transpired for more than one hundred years.

Until then…. We Shall Know Them By Their Deeds.