TULSA – A groundswell of Tulsans closely following the saga of the mass graves at Oaklawn Cemetery are voicing increasing doubts.

Several key members of the 1921 Graves Investigation Public Oversight Committee – a group of Tulsans appointed in 2019 by Mayor G.T. Bynum to give direction to the search for potential mass graves of 1921 Race Massacre victims – have reported that the city is deliberately seeking to draw a cloak over them and their meetings, diminish their role, discourage them from reviewing or openly critiquing the processes and limiting their access to information uncovered in the processes underway.

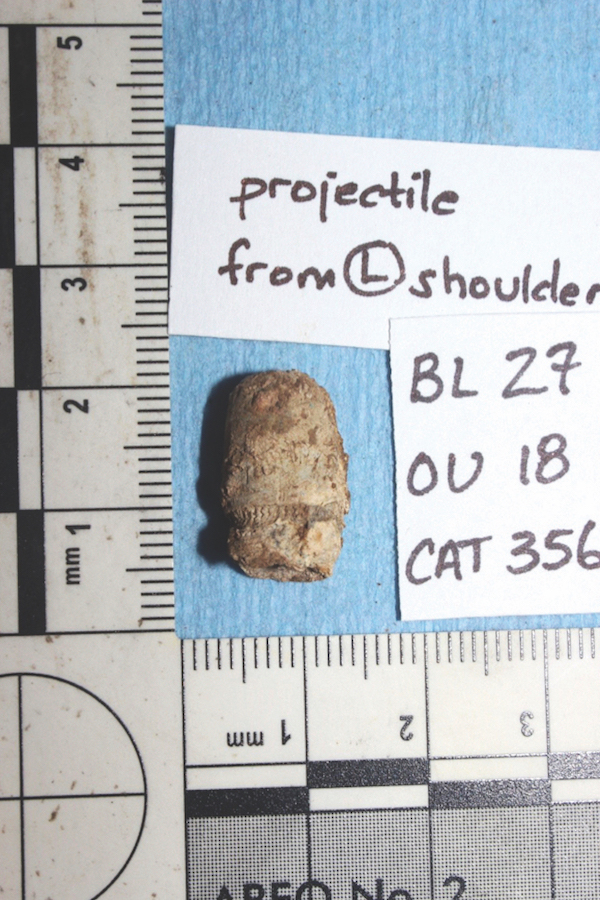

While Mayor Bynum and other city officials initially seemed to favor transparency in the hunt for mass graves, in recent months city officials have abandoned any pretense of openness, said several members of the Oversight Committee. Ever since an exhumed body with a bullet hole was found as part of the course of excavating a mass grave site at Oaklawn Cemetery in June 2021, the city has backed away from direct engaging with the Oversight Committee and the public in general, committee members say.

Committee members interviewed by The Oklahoma Eagle include Greenwood advocate Kristi Williams, City Councilor Vanessa Hall- Harper, State Rep. Regina Goodwin and consultant and public health advocate Sherry Laskey, among others.

They have complained that meetings are not open to the public and limited to closed video conferencing meetings via Zoom.

‘The city got scared’

“At some point, the city seemed to get scared about what they would find in the search for mass graves and decided to diminish the system of public oversight,” said Williams, a descendant of Janie Edwards, a Race Massacre survivor. Williams, who is chair of the Greater Tulsa African American Affairs Commission, feels that the restrictions the city of Tulsa has placed on the committee are the latest in a series of actions that signal that the city does not intend to explore the scepter of mass graves in depth and with the level of professionalism it requires.

The lingering cloud hanging over the mass graves affects the broad community of Black Tulsans far beyond the close circle of descendants of Race Massacre victims. Many bodies of the 300-plus Black Tulsans that a blood-thirsty white mob killed in the Race Massacre remain missing for more than a century. The city’s failure to recover bodies has added to the multigenerational trauma that has affected many Black Tulsans since the Race Massacre.

In 2019, in an apparent attempt to heal the wound, Mayor Bynum launched an investigation into the mass graves. At the time, Bynum created the Oversight Committee and appointed 24 Black Tulsans to it.

“We are committed to exploring what happened in 1921 through a collective and transparent process – filling gaps in our city’s history, and providing healing and justice to our community,” Bynum said at the time.

But since then, by the account of many committee members, the city has systematically removed nearly all of the group’s teeth.

“They have essentially shut us down,” said Hall-Harper, who represents District I on the Tulsa City Council and is also descended from survivors of the Race Massacre.

“It’s not an oversight committee, it’s an out of sight committee” said descendant Goodwin, whose family survived the Race Massacre. She said she believes that the city never took a serious interest in hearing from members of the Oversight Committee.

Laskey said she thinks that initially city officials seemed to want to hear their views. “But then they would show up for meetings, and they would have their agenda and did not seem interested in hearing our input or perspective,” she said. “And it’s been that way ever since.”

As a biologist and former science teacher, Laskey said she was keen to lean into overseeing the procedures of excavating the mass graves and examining the remains found. “But the city didn’t seem to want that,” she said.

Suspensions of city’s motives

Some members of the Oversight Committee have voiced fears that strict control of the process of excavating mass graves by the mayor’s office is a bad omen, possibly signaling that the result of the search for mass graves may be diminished or inconclusive.

“I think they are trying to control the process,” said Hall-Harper. “And the one who controls the process controls the outcome. They have clarified that they see the Oversight Committee as nothing more than a recommending body.”

“If the city really wanted to some resolution of the mass graves issue, you would think they would want to hear from the community,” Goodwin said. “But they don’t want our input. They never have.”

Kavin Ross, chair of the Oversight Committee, a videographer of the Historic Greenwood District and a descendant of Race Massacre survivors, said he is more supportive of the city’s management of the search for mass graves. “Nobody said this search would be quick and easy,” he said. “I feel the search is going in the right direction. We just have to be patient.”

Ross feels that recent announcements, highlighted by the discovery of a second body at Oaklawn with a bullet hole last month, suggest that the city is engaged and focused on the search for graves. He also pointed to a pledge by Bynum in April of 2020 that an additional $1 million would be allocated to the mass graves process.

“The mayor has made a commitment,” Ross said. “He has also given more money. What more could we ask at this stage?”

Williams, Goodwin and other committee members disagree with the chair’s assessment. “Our role should be to hold the city’s feet to the fire,” Williams said.

Mayor’s response

In a Nov. 18 press conference about the mass graves, Bynum sought to explain the city’s shift from the public to virtual meetings for the Public Oversight Committee.

“To make them accessible to both the folks on the Oversight Committee but also anybody else that wants to participate in the meeting, and the reality is at this point there is an international interest in this Investigation, we’ve been doing those meetings virtually to maximize the number of people that can watch them and be able to get information from them,” he said.

The city of Tulsa further defended its investigation of the mass graves in a statement to the Oklahoma Eagle.

“From the beginning of this investigation, we promised we would go where the facts led us and that we would lean on experts and their fields of knowledge to lead this process,” the city said. “Early on in the investigation, we were extremely fortunate that a few of those experts were able to be in Tulsa for those meetings.

“As meetings shifted virtually due to the pandemic, experts in archaeology, forensic anthropology, and forensic science from the east and west coasts of the United States joined in our collective effort to find answers. The most effective solution was to meet virtually not only for everyone’s safety but because of their proximity to Tulsa and busy work schedules.

“Virtual meetings with the Public Oversight Committee have continued, are open to all members of the media and public oversight committee members to record if they choose, and all questions from committee members are heard and answered during those meetings and afterward when requested.

“The City is fortunate to work with members of the Public Oversight Committee and alongside Kavin Ross, a race massacre descendent and chair of the Public Oversight Committee. The same spirit that started this investigation is alive and well, and work continues to find potential victims from 1921 not only during the current excavation work at Oaklawn Cemetery but wherever else the facts and scientific findings may lead us.”

Randy Hopkins, an Oklahoma native, historian, and documenter of the mass graves saga, has suggested that the city possibly violates Oklahoma’s Open Meeting Act by blocking public access to the Oversight Committee.

On Nov. 6, Hopkins sent a letter to the press sharply criticizing the city’s position.

He said: “The current City government is the lineal descendant of the central culprit in the Massacre — Tulsa’s 1921 city government. In effect, the governmental descendant of the chief villain of the Tulsa Race Massacre is now muzzling the descendants of its victims. You can see how that would rub people the wrong way.”

In a Nov. 30 letter to Bynum, Hopkins batted back the city’s attempts to defend its management of the Public Oversight Committee.

“Given your many duties,“ Hopkins told the mayor, “the discrepancies between your public representation and reality may not have come to your attention.

Before the Tulsa Race Massacre centennial commemoration in May 2021, the virtual Public Oversight Committee meetings were preceded by posted public access links. All the meetings were recorded, and those recordings were posted on the city’s Graves Investigation webpage and its YouTube channel.

After the centennial commemoration, someone at the city dropped an opaque curtain between the public and the Public Oversight Committee.