TULSA — Alyssia Hardiman was panicking.

It was February 2021, and she was fresh back at McLain High School for Science and Technology after being confined to home for months as the coronavirus pandemic raged across Tulsa and the world.

Throughout her years in Tulsa Public Schools, the African American teenager had been a high-performing student. She loved learning and at first, was thrilled to return to McLain to finish her senior year. She was so close to graduation, only two credits away — she said she could taste it.

But the atmosphere at McLain left Hardiman anxious.

Everywhere she turned — from the hallways to the cafeteria — seemed packed with students, teachers and aides. Few people seemed to care much about the battery of health regulations established to protect students like her and other school community members from the COVID-19 virus.

Sure, everyone wore masks, following a TPS requirement. But many wore them with their noses exposed or otherwise improperly. COVID-19 vaccinations were voluntary, and by the official account, only a percentage of people in Northside schools like McLain had taken them. And there seemed to be no adherence to social distancing.

Hardiman expressed fears to some teachers at McLain that the school environment felt unsafe. Naturally, protecting her health was a big concern. But her more significant fear was that she could take the COVID-19 virus back home. Five close relatives had already succumbed to the virus — the fear of exposing her mom who was immunocompromised — to the deadly virus haunted the teenager.

After a few days at school, Hardiman shared her despair with Michelle McCane, a trusted McLain teacher and librarian.

“I don’t think I can do this,” she told McCane.

The teacher tried to dissuade Hardiman from dropping out.

The COVID-19 pandemic had left scores of North Tulsa school children behind.

Would Hardiman be one of them?

COVID-19 wreaked havoc on schools

The Oklahoma Eagle has conducted a probe into how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the nearly 33,000 students in Tulsa Public Schools and the surrounding metropolitan area. We conducted more than four dozen interviews with students, parents, administrators and health officials about how the public school community in Tulsa — and surrounding districts — have fared in the three years of the pandemic. The interviewees were drawn from many Tulsa schools, including McLain, Booker T. Washington High School, George Washington Carver Middle School, John Burroughs Elementary School and Emerson Elementary School. We also interviewed teachers and students from Union Public Schools. And we gathered and analyzed the reports and data prepared by TPS and other sources.

The Eagle also interviewed TPS Superintendent Deborah Gist and Board of Education President Stacey Woolley.

We also requested interviews with other senior TPS officials responsible for the system’s pandemic responses. TPS rejected the requests. Drew Druzynski, TPS media relations manager, cited staffing shortages for denying the Eagle’s request.

Our investigation

As we gathered information, it became painfully clear just how much the COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc on public school buildings across Tulsa and created deep fissures among parents, teachers and public officials about mask mandates, school closures and remote learning.

We are publishing a three-part series summarizing our reporting results. In this first article, Part I, we detail the impact that the pandemic has had on the disadvantaged school communities in Tulsa. Despite TPA’s attempts to address the demands of the pandemic, a whole generation of students in our underserved communities have fallen dramatically behind in learning. In Part II, we focus on remote learning: what worked and what didn’t. Part III is devoted to how school administrators make up for the gaps in learning and teaching during the pandemic.

TPS reopening plan

When the pandemic hit in March of 2020, Tulsa Public Schools, like school districts nationwide, were blind-sighted.

“No school system knew what to do,” Gist told the Eagle.

She said Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt was pressuring her — and other school administrators across Oklahoma’s 509 public school districts — to close its schools. TPS closed on March 14, 2020, on orders from the Oklahoma State Board of Education and Stitt’s “stay-at-home” executive order — which extended closures into May and the remainder of the 2019-20 academic year. The order closed all non-essential businesses in all of the state’s 77 counties. In November 2020, there was an effort to reopen TPS schools in phases, but that ended due to a resurgence in the pandemic and the spike in severe cases and deaths.

Working with TPS staff, Gist came up with a plan for their 77 school buildings to return to in-person learning in February 2021. They opened a Virtual Academy for students who felt uncomfortable returning to school in-person. They would pivot to remote learning if cases got too high. Students would all receive passing grades.

“We looked closely at the data available,” Gist said. “We consulted with the best medical professionals, including the Academy of Pediatrics. Our opening plan was based in large part on their recommendations.”

TPS lauded for crisis plan

The California-based Learning Policy Institute (LPI) — an education research and policy advocacy group that focuses on diversity and equity outcomes — conducted a detailed analysis of TPS’s COVID-19 response. The LPI report, published in August 2021, lauded the district’s handling of the crisis.

“Since last year, the district (TPS) has demonstrated that it can educate children in person safely,” noted the LPI report’s authors Jennifer A. Bland Adam K. Edgerton Desiree O’Neal and Naomi Ondrasek. “District administrators estimate approximately 80% of students returned in person by the end of the 2020–21 academic year. From reopening through the end of the school year, case rates did not exceed 0.058% of Tulsa’s in-person students, and the total proportion of students who tested positive or were identified as potentially exposed through contact tracing did not exceed 0.58%. Contact tracing identified the vast majority of positive cases throughout the year resulting from the out-of-school transmission.

“During the final week of school in late May, rates remained very low, with positive cases plus contact tracing affecting only 0.04% of students. By June 2021, new COVID-19 cases in Tulsa County ranged between 160 and 308 per week, down from over 4,000 per week during the pandemic’s local peak in December and January and from nearly 1,200 per week when schools reopened in late February.”

The COVID-19 rage continued

What the LPI study brushed over is that after reopening, the COVID-19 virus continued to plague schools on Tulsa’s Northside — and in other underserved parts of the city.

In the third week of March 2021, for example, half of all the COVID-19 and close exposure cases measured were at Booker T. Washington, North Tulsa’s premier high school, according to TPS reports.

A month later, Booker T. reported a new wave of COVID-19 exposures. In the first week of May 2021, two thirds of all the COVID-19 cases or close exposures reported in the whole city of Tulsa were at Marshall Elementary, located in far North Tulsa on East 56th Street.

The increase in COVID-19 exposures in North Tulsa schools should have come as no surprise. For much of the winter and spring of 2021, the rates of COVID-19 in most Northside zip codes were in the high alert “Red Zone,” according to data released by the Tulsa Health Department. THD recommended that residents in such areas stay at home except for essential outside activities.

Still, schools struggled to remain open. Each time COVID-19 cases or exposures called for a last-minute switch from in-person to online learning. And remote learning brought its own set of challenges, which we will explore in part two of this series.

The strains of the pandemic resulted in a drop in the numbers for all aspects of the school system, including teachers, administrators and students. In October 2020, when COVID-19 cases were on a sharp rise, the total number of kids enrolled in TPS fell to 32,323, a sharp decline from the 36,623 count just a couple of years earlier. In October of this year, the level of enrolment had crept back to 33,873, still nowhere near pre-pandemic levels.

But the starkest indicators of the adverse effects that COVID-19 had on students’ learning are the test score records before and after the peak of the pandemic.

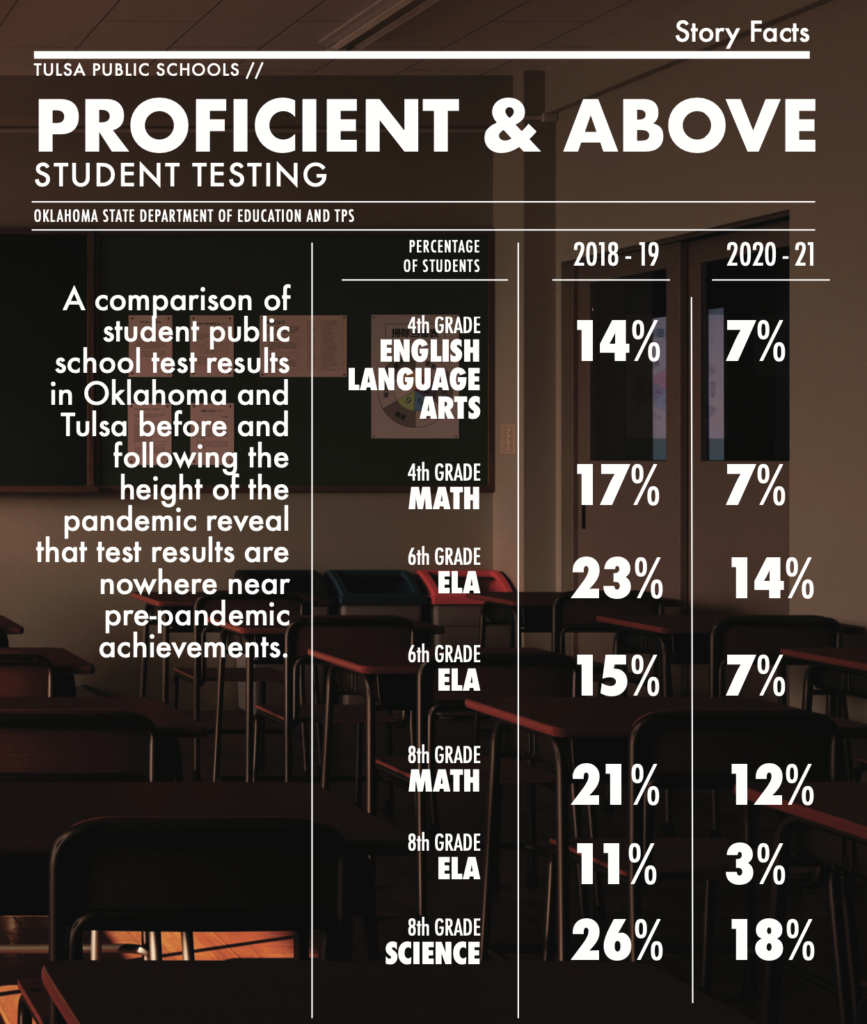

Earlier this year, the Oklahoma State Department of Education and TPS released scores from the Oklahoma School Testing Program. A comparison of student public school test results in Oklahoma and Tulsa before and following the height of the pandemic reveal that test results are nowhere near pre-pandemic achievements. Comparing test scores from TPS from school years 2018-19 to 2020-21, students testing proficient and above fell dramatically. They fell in every category measured and every grade tested, 3rd through 8th grades. As an illustration, the comparative achievement test results for the 4th, 6th, and 8th grades are as follows. (ELA is English Language Arts).

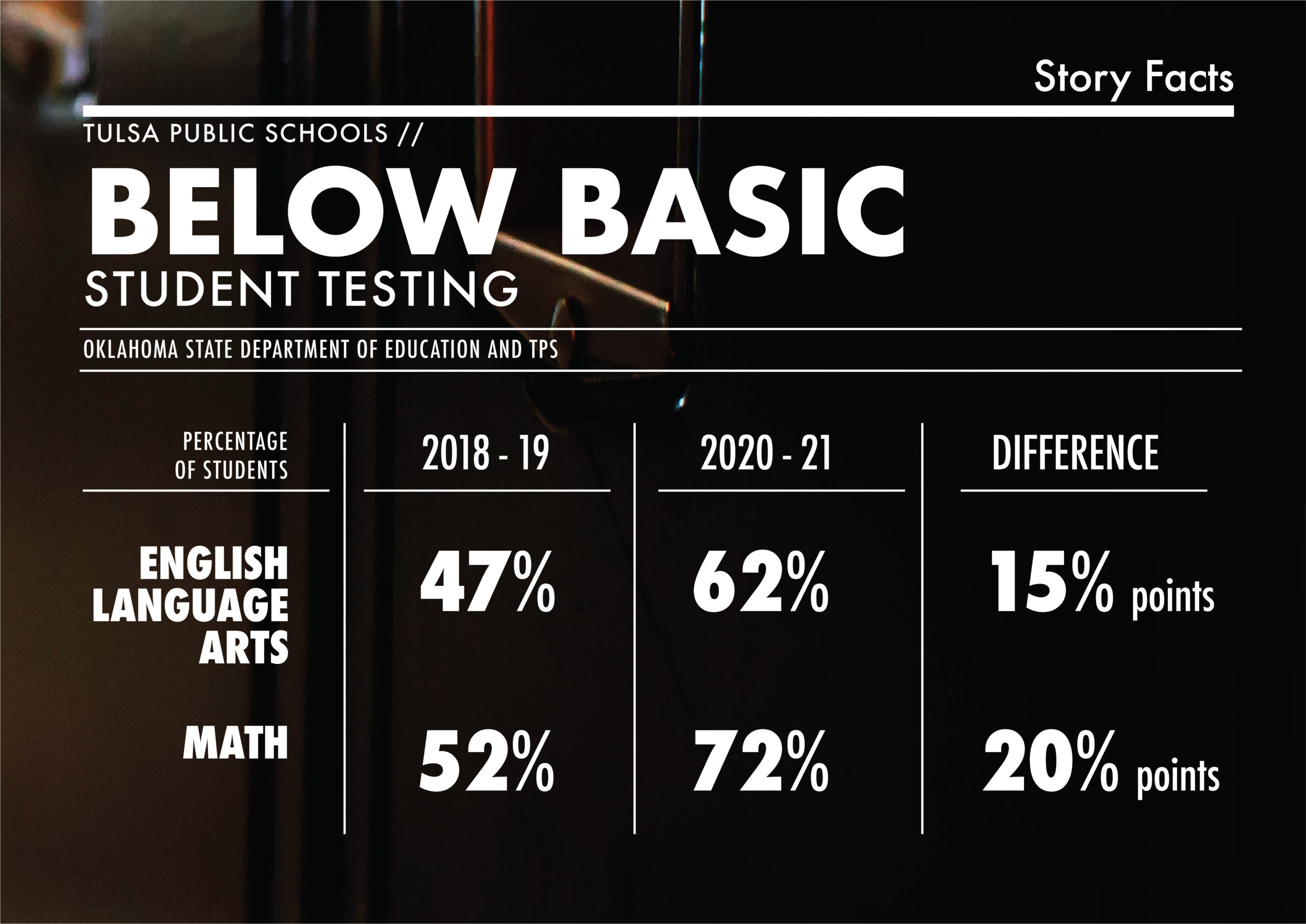

And while on average, 8.5% fewer students tested proficient and above in the wake of the pandemic, many more plunged into the “below basic” category. For example, comparing English Language Arts and Math as core curriculum, again grades 3-8, Tulsa Public Schools students tested as follows:

The first nationwide comprehensive survey and study of the pandemic effects was released using data for the years 2019 and 2022. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) tested students aged nine across the country. The testing showed reading scores fell a statistically significant 5 points and declined by 8 points in mathematics. The pandemic more adversely affected students who previously performed poorer in testing. Their scores plunged by much more significant margins than the average scores decline. Also, minority scores declined more than whites. For example, the study cites, “White-Black gap widens by 8 points in mathematics.” The authors speculated this difference likely reflects a resource gap.

Low Income and minorities hit the hardest

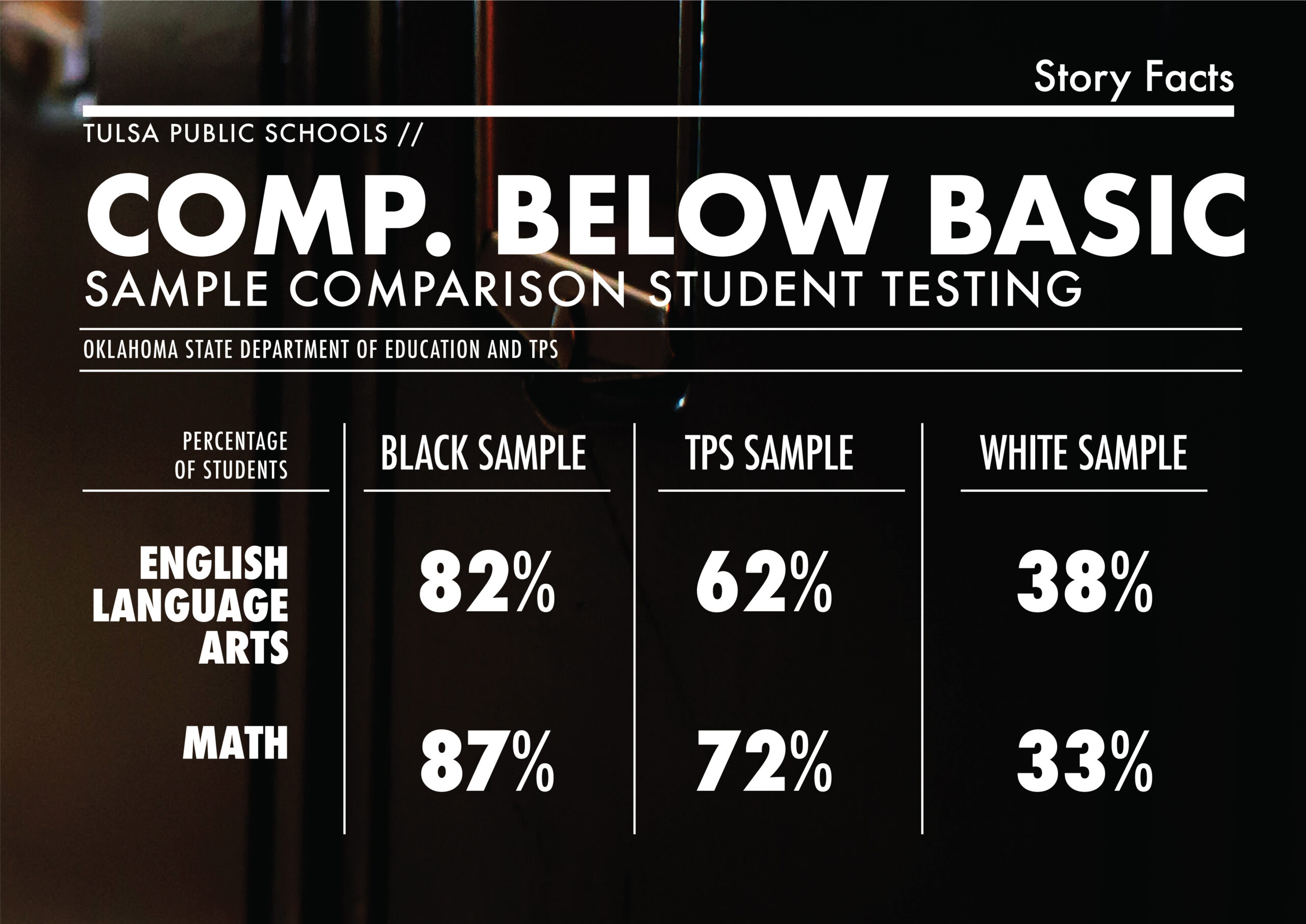

Similar to the national study finding, TPS students who were poor performers in academic testing were hit hardest by the pandemic and had their test scores more adversely affected. Black and Brown students in Tulsa were similarly adversely affected.

The Eagle acquired test scores to sample and measure this disparity. Four predominately white schools in high-income areas were compared with four predominately Black schools in low-income neighborhoods. Here’s how those samples were compared in the “below basic” category in 2020-2021 with the TPS average.

Teacher departures

The impact on students in the Northside went far broader and deeper than classroom performance.

Dr. Kyla Lussier, the psychiatrist at the Historic Greenwood District-based Morton Health Clinic, counselled many North Tulsa students and their parents during the height of the pandemic. She reported that the pandemic brought her clients a wide range of challenges — from physical abuse and harassment to depression.

In an interview with the Eagle, Dr. Lussier described the social impact the COVID-19 era had on many kids on the Northside. “Kids were left home alone,” she said. “Sometimes parents quit their jobs, and they didn’t have income. So, there was no food at home. And of course, that created unimaginably stressful situations.

“On top of all that, you had young kids who didn’t have access to their friends or other social development tools that were most important at this phase of their lives. And they didn’t have access to teachers, either. For many of them, teachers are the only bright spot in their day because the home can be unstable. You couldn’t make them do their homework, either.

“So many kids got depressed. And none of this is far from over,” she said.

Teachers in North Tulsa schools also suffered.

The pandemic brought on an exodus of teachers that remained unresolved at the beginning of the current school year. In August 2022, TPS reported that the system was 100 teachers short, including positions at Booker T., Carver and other Northside schools.

And many of the teachers who stayed were conflicted about TPS’s policy requiring masking. “Some didn’t want to wear masks,” Dr. Lussier said. “Others were afraid they would take the virus home to their kids.”

A high number of teachers quit or were fired. Many of the replacement teachers at Booker T. and other Northside schools seemed subpar, according to feedback from several students and their parents.

The most worrisome group of students of the COVID-19 era we identified in Tulsa were those who had been left out of the traditional learning experience for six months up to almost three years. For some this educational gap was by choice.

For others, the flawed system allowed them to go for extended periods without engagements with teachers in a classroom setting. The huge gaps in classroom exposure and lax requirements system imposed by TPS allowed students to opt out of classroom settings. And even those who showed up had little incentive to, the edict that no student would fail took away the incentive many students had to try.

Student lament to school board

Jaden George, who graduated from McLain in 2022, went before the Tulsa board of education last May to complain about the shortcomings in the education he had received at McLain.

“We don’t have skills to apply for jobs or do interviews, resumes, no models for interviewing,” he told the seven-member school board. “No plans for the future. Not knowing how to do adult things. Lack of connections. No networking ability to move into professional things. I also do not feel my education has adequately prepared me for life after high school.

“We aren’t being challenged to read, write or give speeches.”

George’s remarks seemed to capture the sentiment of other students during the pandemic: that Tulsa Public Schools and the educational system had failed them.

‘So, why bother?’

Many other Northside students we interviewed reflected George’s despair.

Most asked not to be identified by full name.

Aaron, an African American junior at Central High School, said since his father lost his job during the pandemic, he got a job to help make ends meet. Working 40 hours a week at a convenience store left no time for studies.

Carol, 17, a sophomore at Will Rogers High School, said she had no Internet connection at her home during much of the pandemic and did not feel safe going to off-site locations for remote classes.

Benjamin, a junior at McLain, tried to participate in remote learning but found it too complicated and so gave up. “We were all told we were going to pass anyway,” he said. “So why bother?”

McCane — the dedicated librarian, teacher and mentor for many students at McLain during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic — said she feels that the pandemic exposed — and often magnified — the challenges McClain and other schools in Tulsa’s underserved communities have faced for years. “Our school community had been suffering significant challenges for years,” she explained in an interview with the Eagle. “Many students had to hold down jobs. Other students were behind in their learning comprehension. Parents were too busy to be engaged. All these things had been problems for years. And they became even bigger problems during the pandemic.”

McCane feels that the TPS administration “did the best they could given the resources and information that was available.”

For Darryl Bright, founder, and executive director of Citizen’s United for a Better Education System (CUBES) and a longtime advocate for education in North Tulsa, the pandemic solutions applied by TPS were not designed for Tulsa’s underserved community.

“The district’s plan may have worked for families who were affluent enough to have a parent at home full time or have great Internet at home or have a good comprehension of the lessons,” he said.

“But in our community, you have second graders who can’t read. You have eighth graders reading at the sixth-grade level. You have houses with no Internet. You have working-class parents who can’t afford to stay home. You have parents or grandparents who are not well-versed in using the Internet. You have kids who were left to babysit their younger brothers and sisters. Whenever plan TPS rolled in was inadequate for the culture of North Tulsa.”

‘The pandemic was a setback’

Black, Brown and low-income students were not the only ones placed off course by the pandemic and TPS’s management of it. Cyrus Carter, a mixed-race student with professional parents who was a senior at Booker T. in the 2019- 2020 school year, shared his frustration with the approach TPS took.

“It’s not just the two months you lost. You lost everything that went with it,” Carter said in an interview with the Eagle. “I lost AP tests I was preparing for and final exams in classes that I was interested in and passionate about.

“Being out of school for the first six months of the pandemic was a setback. That’s like a six-month summer. That’s a long time to take a break from doing anything challenging, having any classroom engagement. So, of course, by the time I got to college I was stressed.”

But the underserved kids were far more deeply impacted. Every counselor or mentor of school kids on Tulsa’s Northside told a story of a child — or in some cases, several children — whose schooling was severely disrupted by COVID-19.

McCane, the former McLain teacher, said some students opted to use their free time available during the pandemic to get jobs rather than keep up with school work.

Bright, the C.U.B.E.S. director, shared the story of a family with young school children but no Internet at home and thus no opportunity to participate in remote learning. Oklahoma ranks 10th for the least connected state or “Internet desert” in the United States.

Devin Williams, co-owner of A New Way Center, a mental health care service in the Historic Greenwood District, spoke of a young boy who had suffered the physical abuse of a father, who was stuck at home without a job. “Unfortunately,” Williams said, “there are many such cases.”

Finding a way to succeed

Yet, some students at McClain and other Northside schools managed to overcome the most brutal barriers posed by the pandemic.

Nataly Gomez is one example.

Like most of her classmates, Gomez was challenged by the COVID-19 pandemic and its restrictions on learning. But she decided she was not going to be daunted. She used the available tools to continue her classes even during the problematic 2020-2021 school year.

“I wanted to finish as quickly as I could,” she said.

Her biggest motivation was to help others. Gomez said a circle of teachers and administrators helped guide her to build up enough credits. In the end, Gomez graduated a year early from McLain. She said she quickly got a job to help her family.

Leaving McClain, finding a way

Hardiman, the McLain student who feared that she would get the COVID-19 virus and take it into her home, also found a positive path forward.

She left McLain.

But, with the assistance of counselors and teachers, she was enrolled at Street School at 1135 S. Yale Ave. The smaller class sizes and better mental health system at the school gave her the support she needed. In the spring of 2022, serenaded by her family and mentors, Hardiman graduated from high school.

These bright sagas aside, many Northside students finished the 2020-21 and 2021-22 school years unprepared for the next stage of school — or life.

Some students who received passing grades — despite having taken no classes — now had to find ways to recover what they had missed.

The students who had tricked the system by clocking in for remote courses and going back to sleep are now faced with learning gaps. Students who missed basic lessons in math, English or other classes are unprepared to enter the work world.

Superintendent Gist concurs.

Surveying how Tulsa’s schools under her watch have fared in the past three years of the pandemic, she said, “we are doing the best with what we have to work with.”

And yet, she added, “we’re still struggling. We’re struggling with resources, teacher shortages and learning gaps. Our approach to the pandemic is a work in progress.”

About This Series

The Oklahoma Eagle is investigating how the coronavirus pandemic impacted the education of the Black and Brown children in Tulsa Public Schools. In the first installment of our three-part series, we detail the impact the pandemic has had on the disadvantaged schools in our community.