By THE OKLAHOMA EAGLE

“Politics is a feral beast, composer of sonatas, and a glutton for the souls of men.”

The abstract is a useful tool for capturing the full spectrum of the nature of politics, its darkest and brightest persona. It also serves as a reminder to anticipate every measure of behavior from politicians. Enter, the 2022 Oklahoma Governor’s race candidates and the chorus of operatives who have wasted little time crafting messaging firmly anchored within the “Scary Black Men” trope, featuring Oklahoma native Lawrence Paul Anderson, felon and cannibal.

It only seems like yesterday when Republicans, like the trolls of J.R.R. Tolkien’s middle-earth, tormented then-U.S. Circuit Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson during Senate Judiciary Committee hearings, framing race, most specifically her acknowledgement of the troubling intersectionality of race and politics, as a rational justification to reject her nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court. Brown’s face, the background image of widely shared social media memes, became the canvas upon which “red-blooded, God-fearing, real Americans” crafted hate-filled racist messaging. The politics of race, once again, produced yet another Black face to represent manufactured fear.

The Senate committee hearings, slash, farce, were not a new phenomenon within the realm of politics as we have traveled upon this pothole speckled road before. Many Americans remember the 1998 Presidential race, when manufactured statesman then-Vice President George H. Bush, secured the Republican Party nomination and would soon find himself fighting for what would become a single-term political future. Bush, vastly dissimilar to his more charismatic predecessor, relied upon the economic growth and anti-crime policies championed by the Reagan administration. The Republican candidate quickly gained traction nationally after the Republican National Convention, advancing towards an unprecedented electoral college wins in California, Illinois, New Jersey, Maryland, Connecticut and other traditional blue states.

The “kinder and gentler” Republican candidate, although well-ahead in national polls, sheepishly benefited from a series of broadly considered racist campaign ads targeting his Democratic opponent, Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis, as “soft on crime.” The weapon of choice, for Bush’s supporters, was of course the “Scary Black Man.”

Republicans were keenly aware of the potential benefit of instilling fear throughout the electorate, creating an irrational vulnerability amongst suburban families. Bush campaign officials and supporters – owing some credit to Sen. Al Gore, who first introduced the topic of Massachusetts’ weekend furlough program during the Democratic primary – discovered Willie Horton, their “Scary Black Man.” Horton, a convicted murderer sentenced to life in prison for the 1974 slaying of a 17-year-old gas station attendant, was allowed to participate in the states’ furlough program in 1986. After being granted a weekend furlough, for no less than nine times prior, Horton failed to return to the Massachusetts prison, and remained on the run for approximately 10 months. In April 1987, Horton twice raped a woman and savagely beat her fiancé, stole the couple’s vehicle, and was later captured by the Prince George’s Country Police.

The “soft on crime” rhetoric of the 1980s undergirded a legacy of policies and laws that yielded a disproportionate application of justice for Black Americans. Forty years later, we continue to live within the wake of poorly considered legislation like the federal Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the “three-strikes laws,” and mandatory minimum sentencing, which have gutted Black communities. Republicans, conservatives and moralists, predictably, rely upon the rhetoric of fear to explain our country’s economic challenges, consistently assigning blame to a brown face, as this approach appears to have worked for former Presidents George H. Bush and Donald J. Trump.

Guilt, established by our judiciary, is not a requisite state for the role of “Scary Black Man.” Dick Rowland, the 19-year-old Black Tulsan accused of assaulting a young white teen on the Drexel Building elevator in downtown Tulsa, was not afforded the long-heralded “due process” that white Tulsans held so dear at the time. The accusation, nothing more, possessed sufficient measure and concern to fuel the mass murder of more than 300 innocent Greenwood residents. Rowland quickly became the city’s “Scary Black Man,” referenced as the “Negro” in the Tulsa Tribune, who must be feared and ultimately captured.

Today, Oklahoma’s Republican Party – never willing to break the cycle of overt racism – has discovered its “Scary Black Man” just in time for the 2022 gubernatorial race, and his name is Lawrence Paul Anderson. The party’s new strawman shares a similarly horrific journey with Horton, marked by Anderson’s violent crimes. That the murder and postmortem vile acts weren’t enough to compel all Oklahomans to demand an explanation as to why Anderson was released, Republicans have instead decided to weaponize the crimes by attempting to convince the electorate that they too could suffer a similar fate if they don’t cast their votes in support of a “tough on crime” candidate.

In support of a more anti-justice Oklahoma candidate, Conservative Voice Of America (CVA), a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit, produced an ad claiming “Gov. Stitt’s catch and release policies led to the largest mass release of felons in U.S. history. One felon released by Gov. Stitt was Lawrence Anderson. Anderson brutally murdered his neighbor, then tried to feed her organs to his family. When his family refused, Anderson killed them, too.”

The 30-second campaign spot, littered with familiar triggering rhetoric, is anchored by Anderson’s image. The intent was quite clear, establishing a visual connection between crime and fear. Anderson’s Black face now represents fear, what is possible if “the socialist liberals” defund the police or teach our children critical race theory.

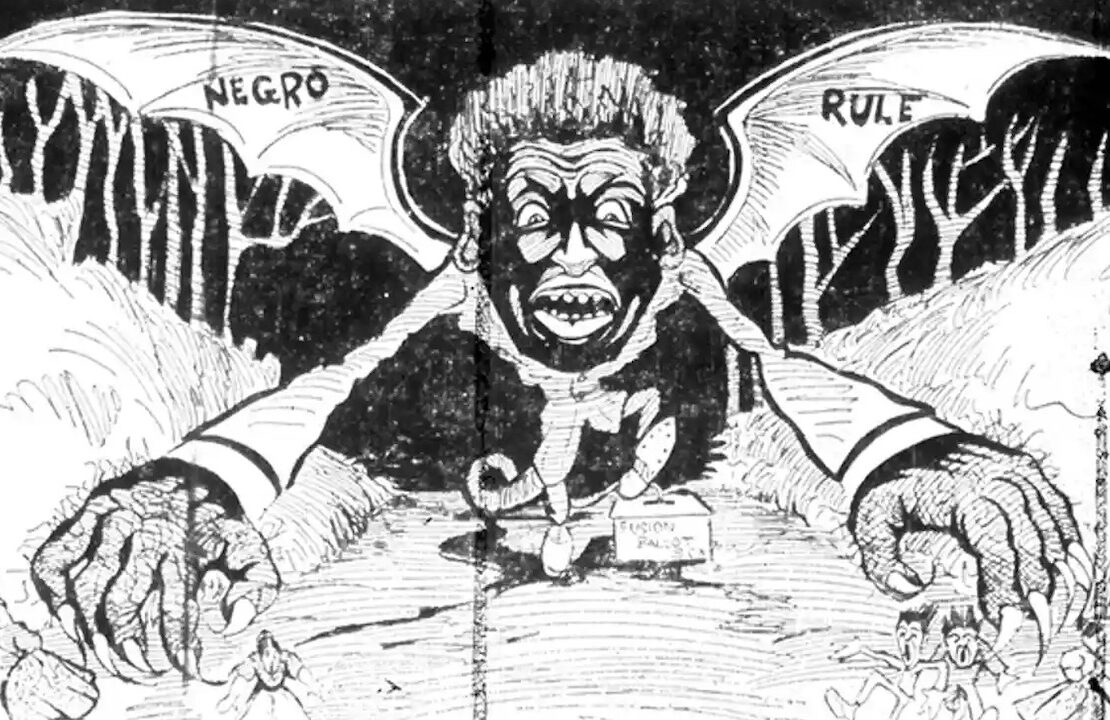

American politics has relied upon the consistent effect of the “Scary Black Man” for more than 100 years. Historians have adequately recorded the roots of the Ku Klux Klan and their usage of imagery to incite fear. Upon its founding in 1865, the Klan soon relied upon the controversial depictions of cartoonist Thomas Nast to advance white supremacy. Democratic-controlled newspapers throughout the state of North Carolina, stalwarts of state’s rights, published cartoons about the horror of potential “Negro Rule.” The News and Observer (1898), of note, depicted the looming image of a Black man terrorizing white citizens should Black Americans be afforded the right to serve as legislators. The referenced norms of Reconstruction represent a few of many that define the course of our sordid history and provide context for our shared experiences today. We are only required to reflect again upon the caricature pursued by Republicans during the Jackson Senate Confirmation Hearing. Americans were instructed to believe that Brown posed an existential threat to our future prosperity, that we were to look upon Brown and all others like her, with the same lens as The News and Observer’s editorial of more than 100 years pass.

Anderson, certainly, will not be the last of those Black faces to be weaponized, legislated against, avoided with every measure, distrusted, and feared.

Republicans, certainly, will continue to embody the epitome of politics-gone-wrong, man’s worst instincts for survival, the antithesis of a righteous faith, and ironically, an existential threat to our future prosperity.