LOCAL & STATE

Ross D. Johnson, The Oklahoma Eagle

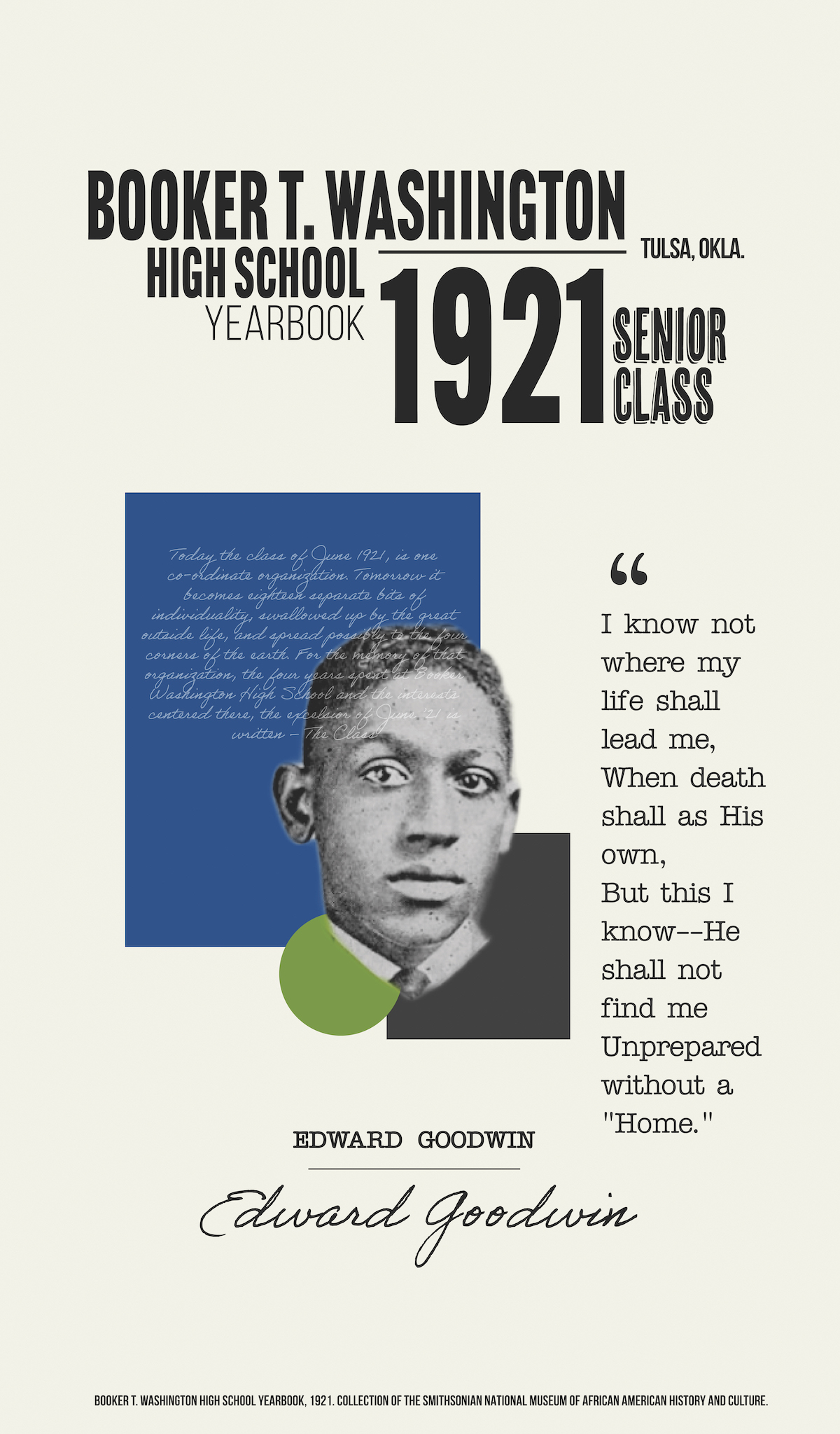

Edward Goodwin, 1921 Booker T. Washington High School senior, Tulsa, Okla. Goodwin was one of eighteen graduates featured in the 1921 yearbook, archived by the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, D.C. Illustration, The Oklahoma Eagle

Long years ago, a hoary haired prophet said in the golden years to come a class of girls and boys would descend from the blue skys [sic] above––and that these people would startle the world. The class has arrived––in the form of June graduates 1921.

1921 BOOKER T. WASHINGTON HIGH SCHOOL YEARBOOK

Certainly, by today’s standard, the 1921 Booker T. Washington High School’s graduating class of eighteen students, thirteen and five young ladies and men respectively, would appear small.

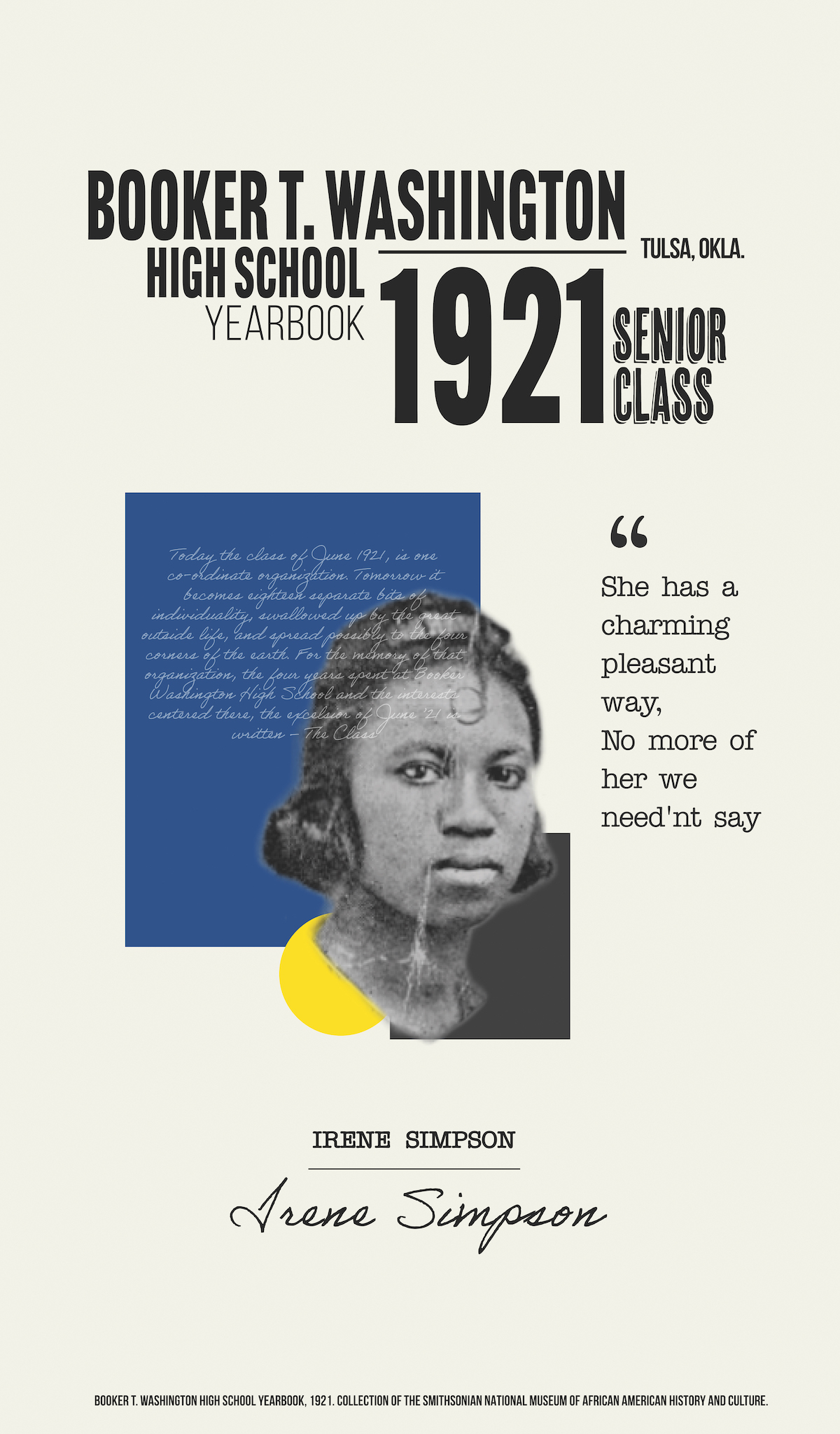

Irene Simpson, chair of the student government social committee, assumed a coquettish nature, as described by her classmates in the archived yearbook.

The Sweet Girl Graduates, a three-act performance that featured many of the 1921 graduates, would cast Simpson as Miss Matilda Hoppenhoer, the aunt of the lead character Miss Maude De Smythe, The Sweet Girl. Simpson’s performance, we’re certain, was well-received.

The senior with “a charming pleasant way” would soon complete required coursework, stand proudly next to fellow graduates, then step forward into a world challenged by racial segregation and violence.

Her [Simpson’s] future, envisioned by peers, was a life of adventure, perhaps beyond the borders of the historic Greenwood district.

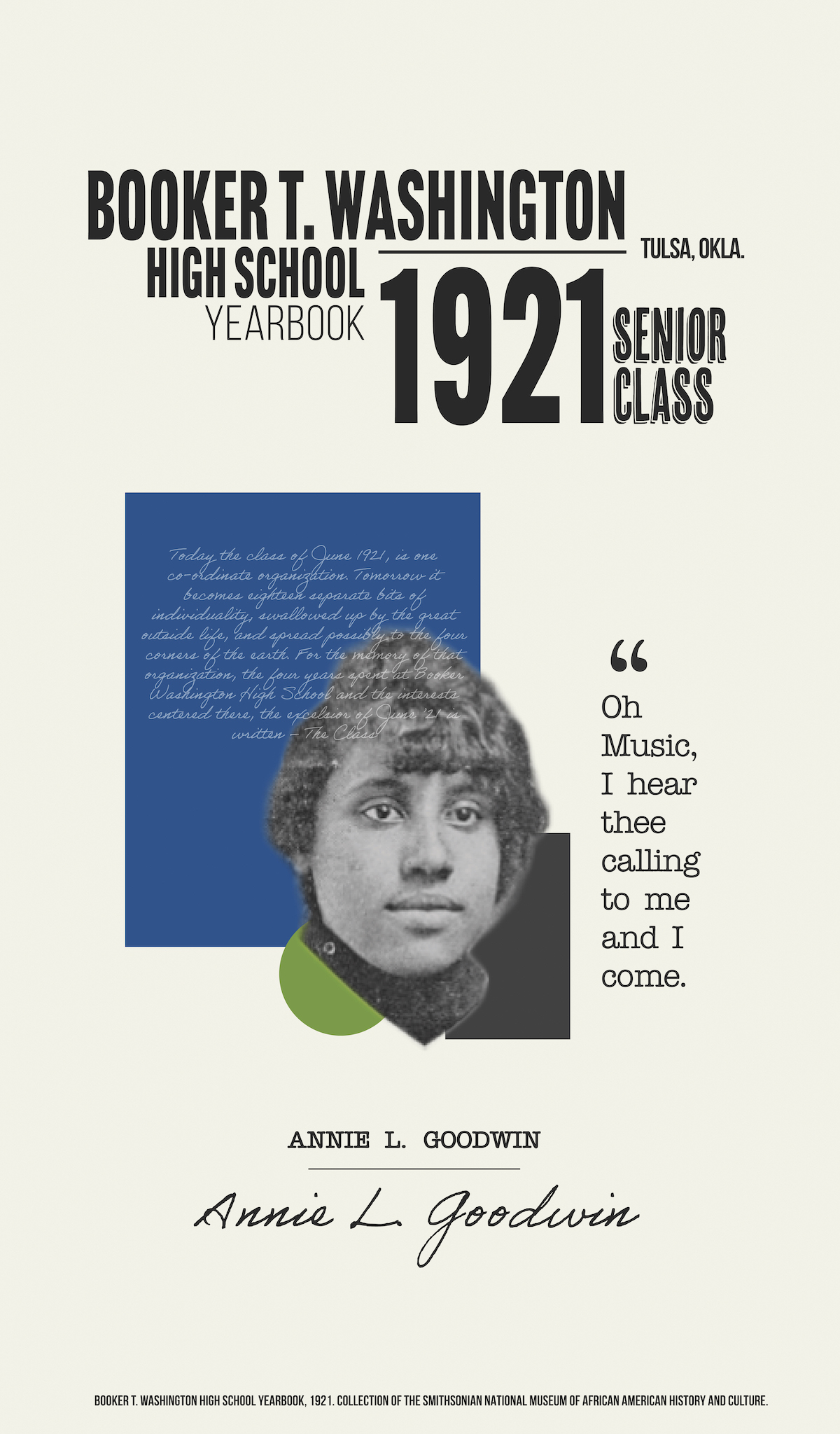

Anna Goodwin, president of the class’s student government, could seldom be described as dispassionate. The senior, known for her “rapid speech” and self-confidence, undoubtably inspired her peers. Goodwin’s hobby, literature, would well-prepare her any professional aspiration.

Goodwin, like Simpson, was cast in The Sweet Girl, assuming the lead role of Miss Maude De Smythe, the Secretary of the Class of 1902.

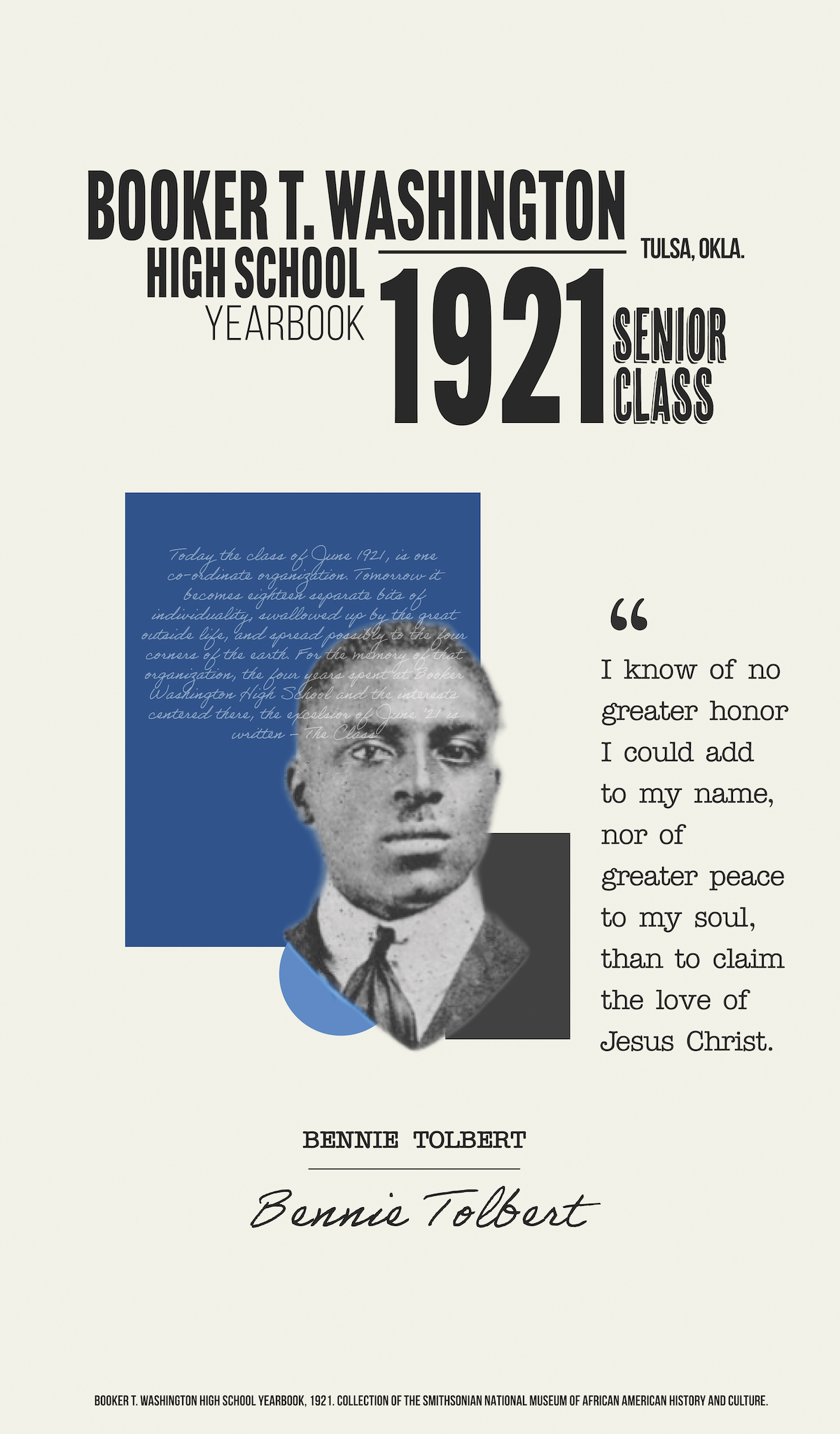

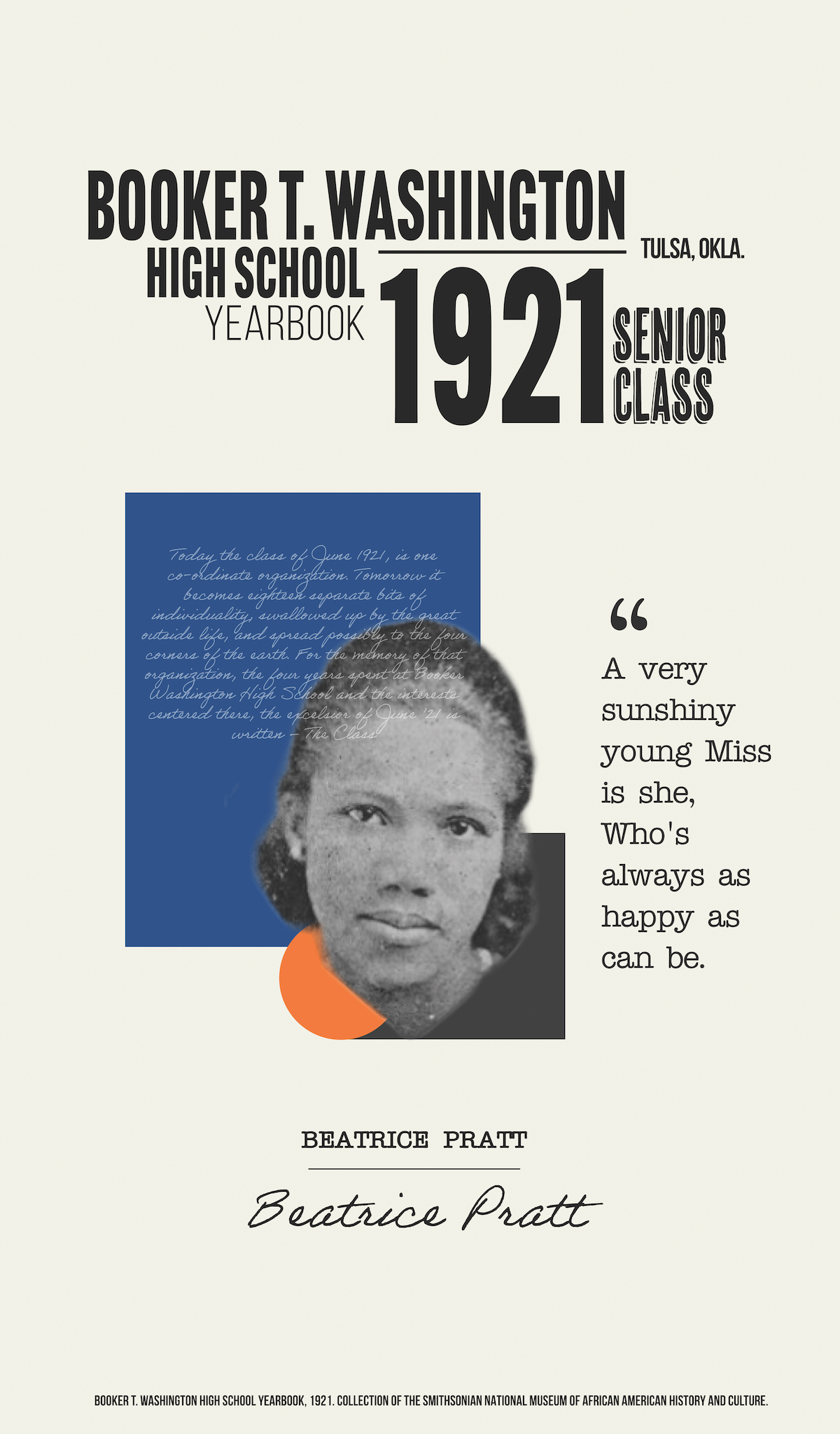

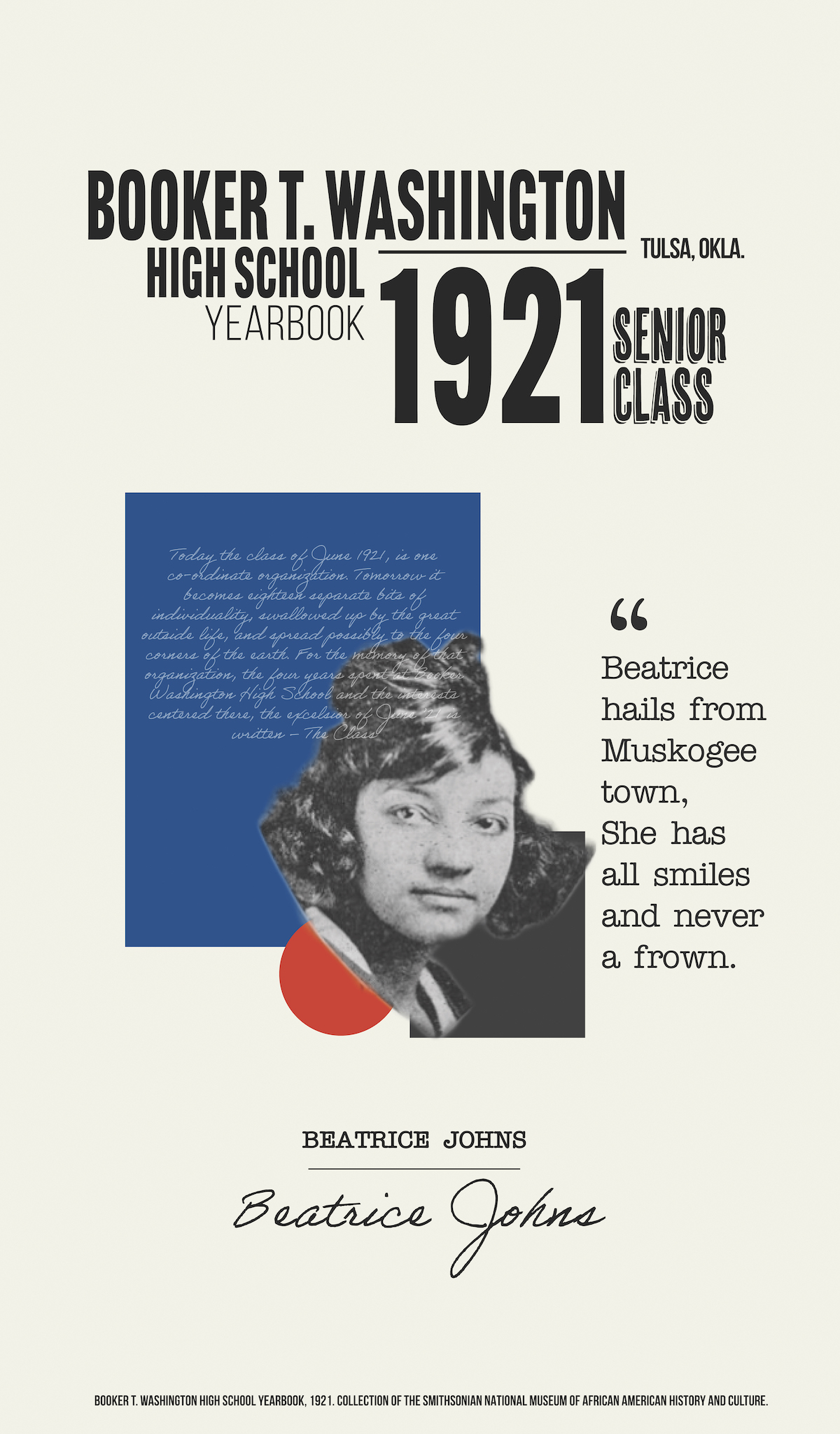

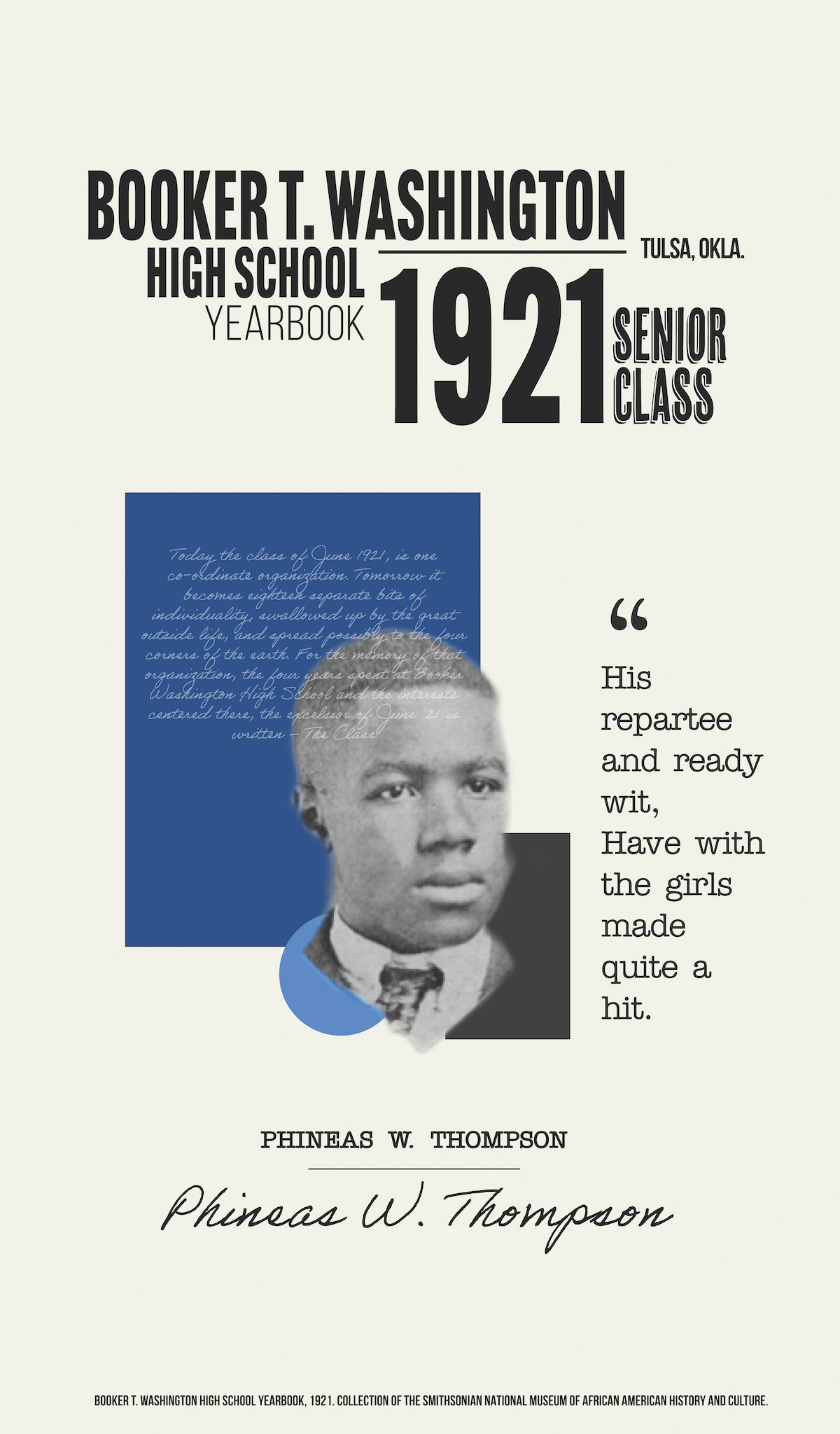

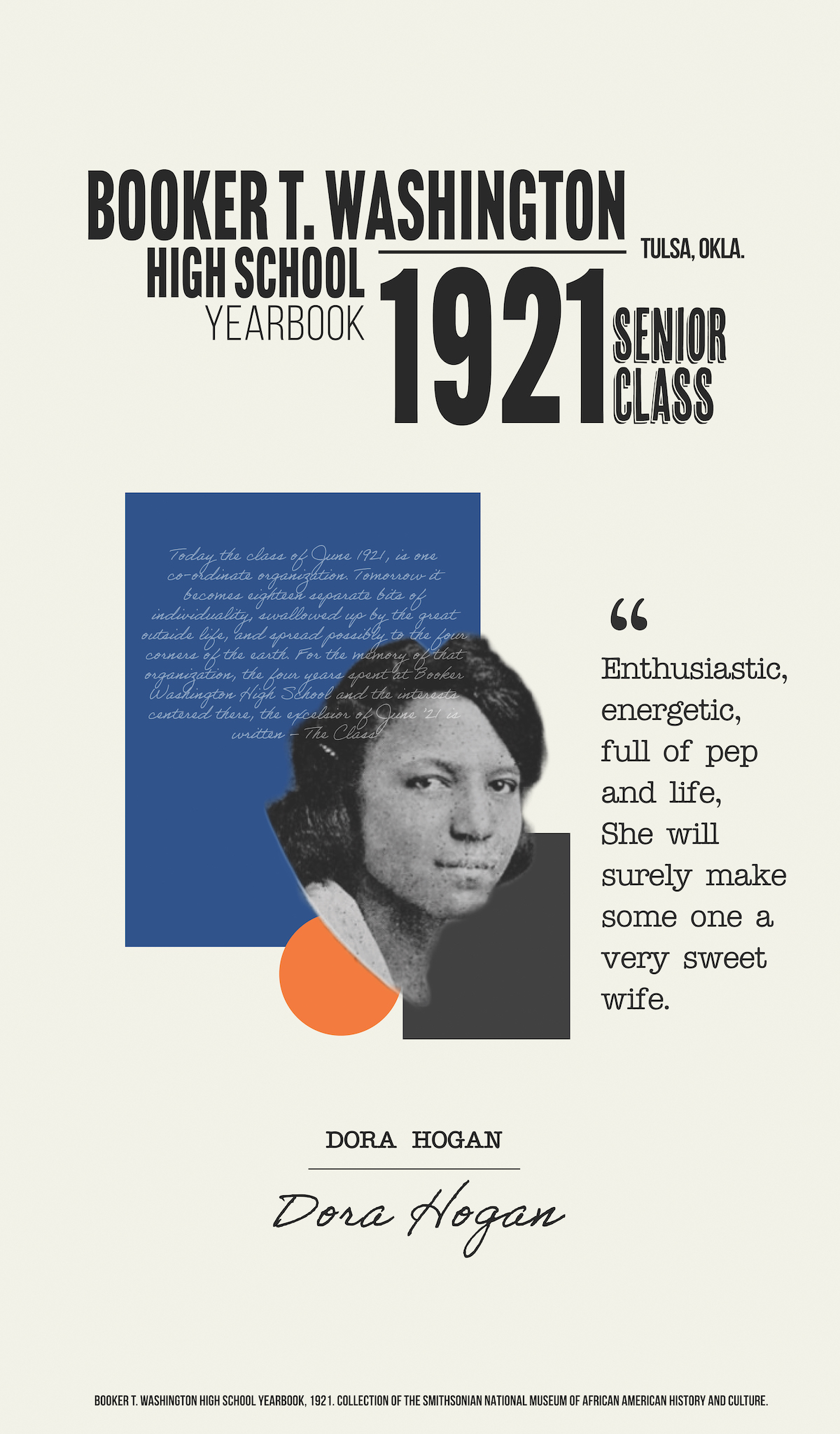

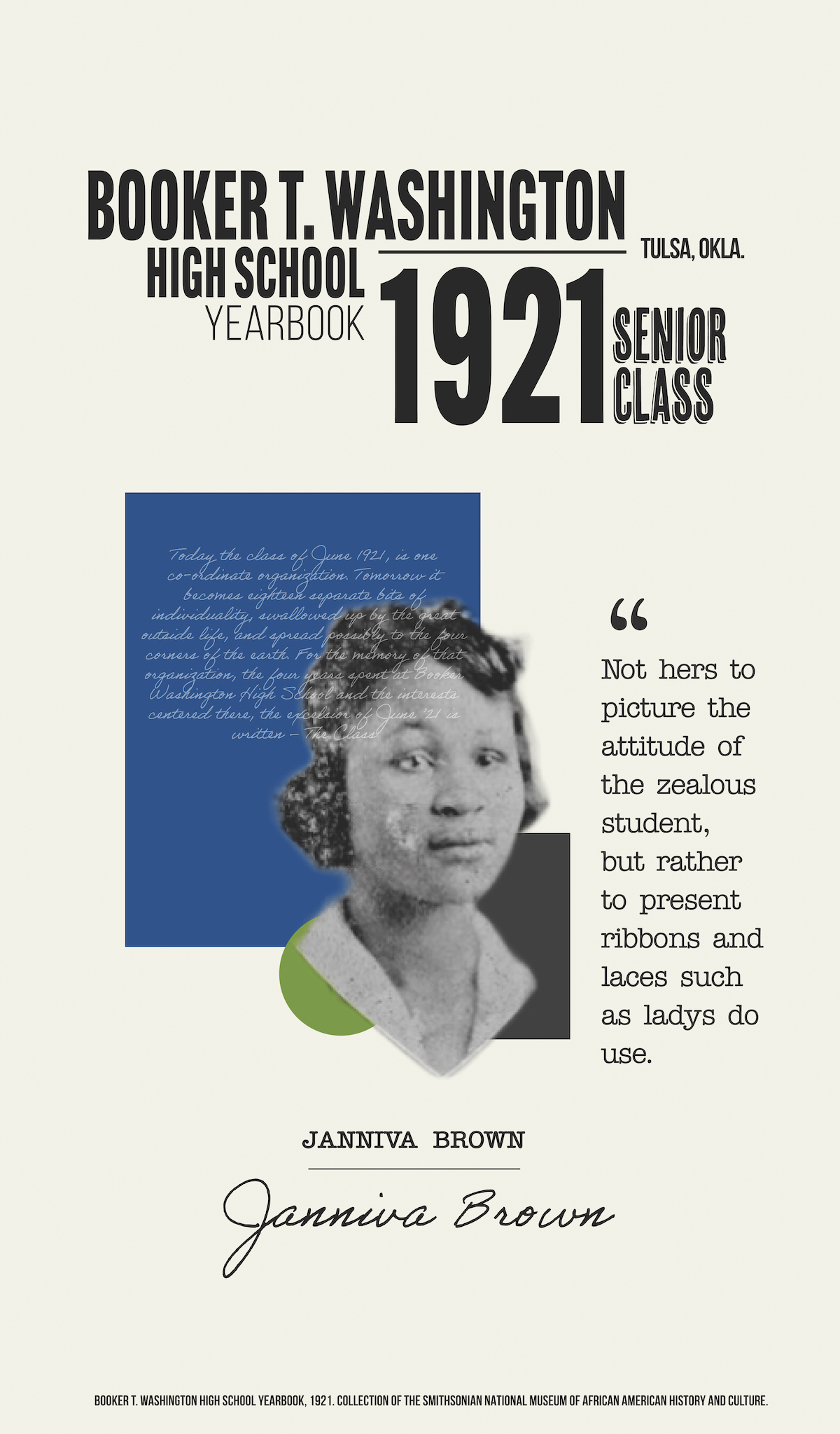

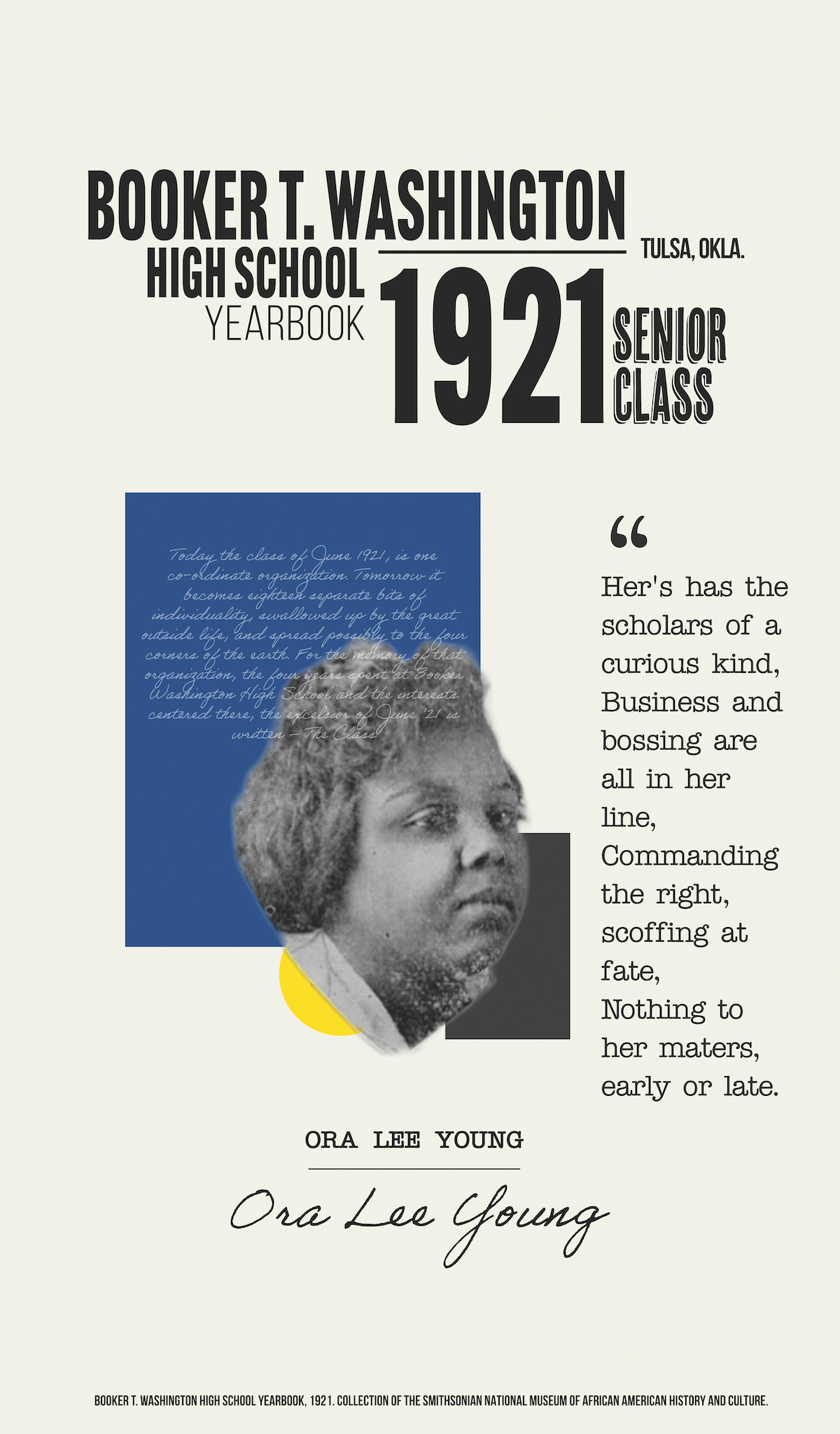

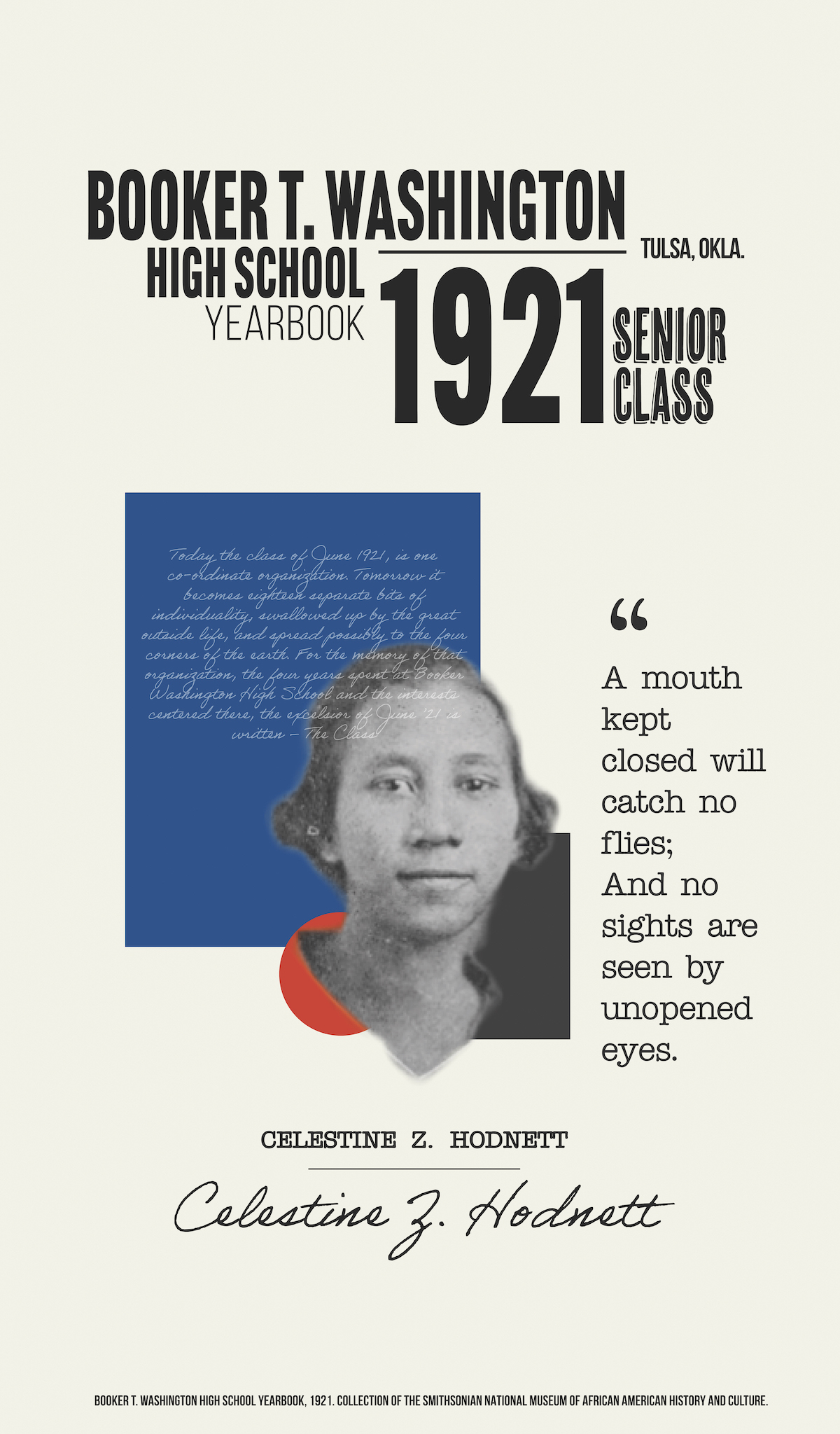

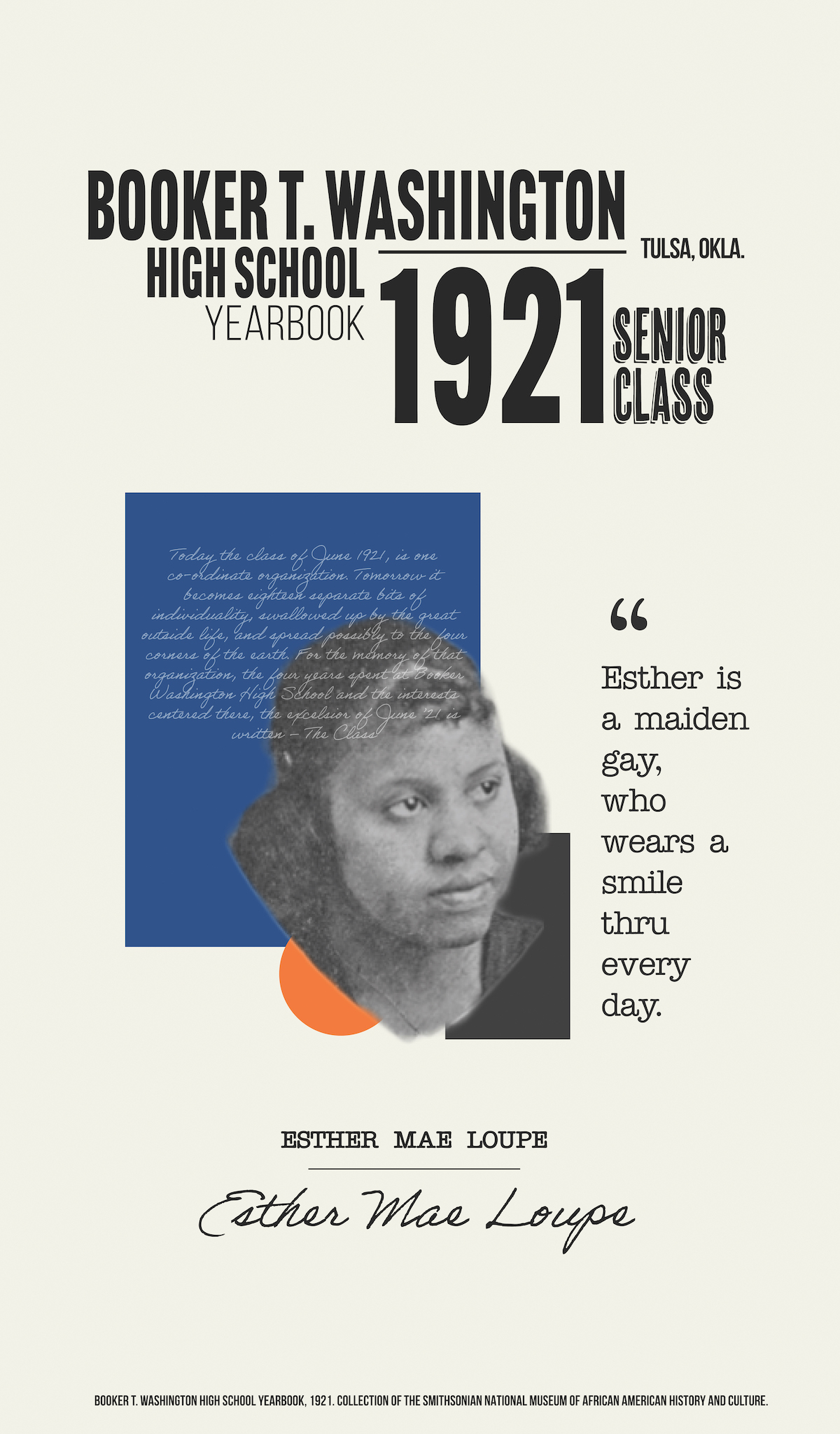

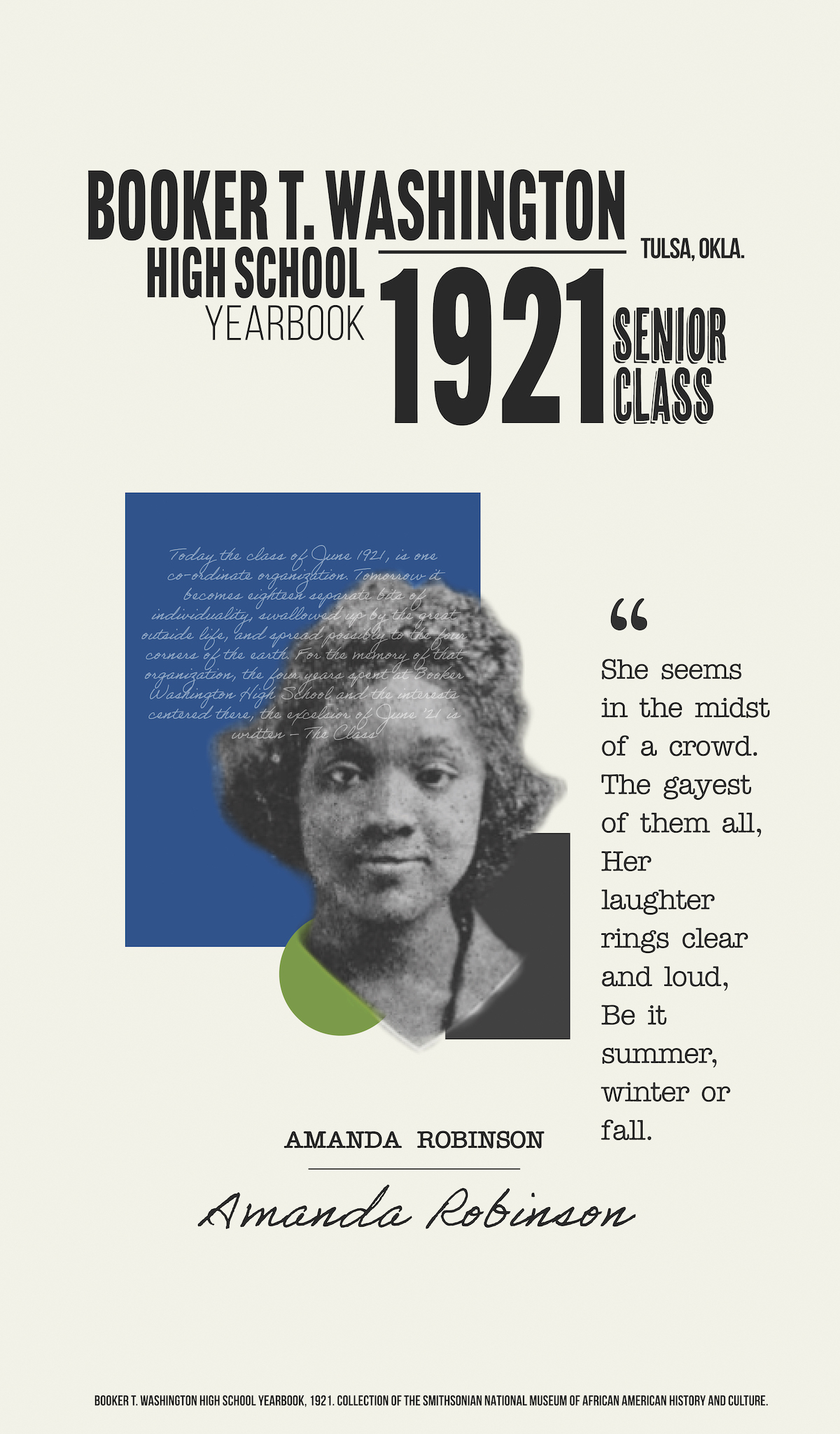

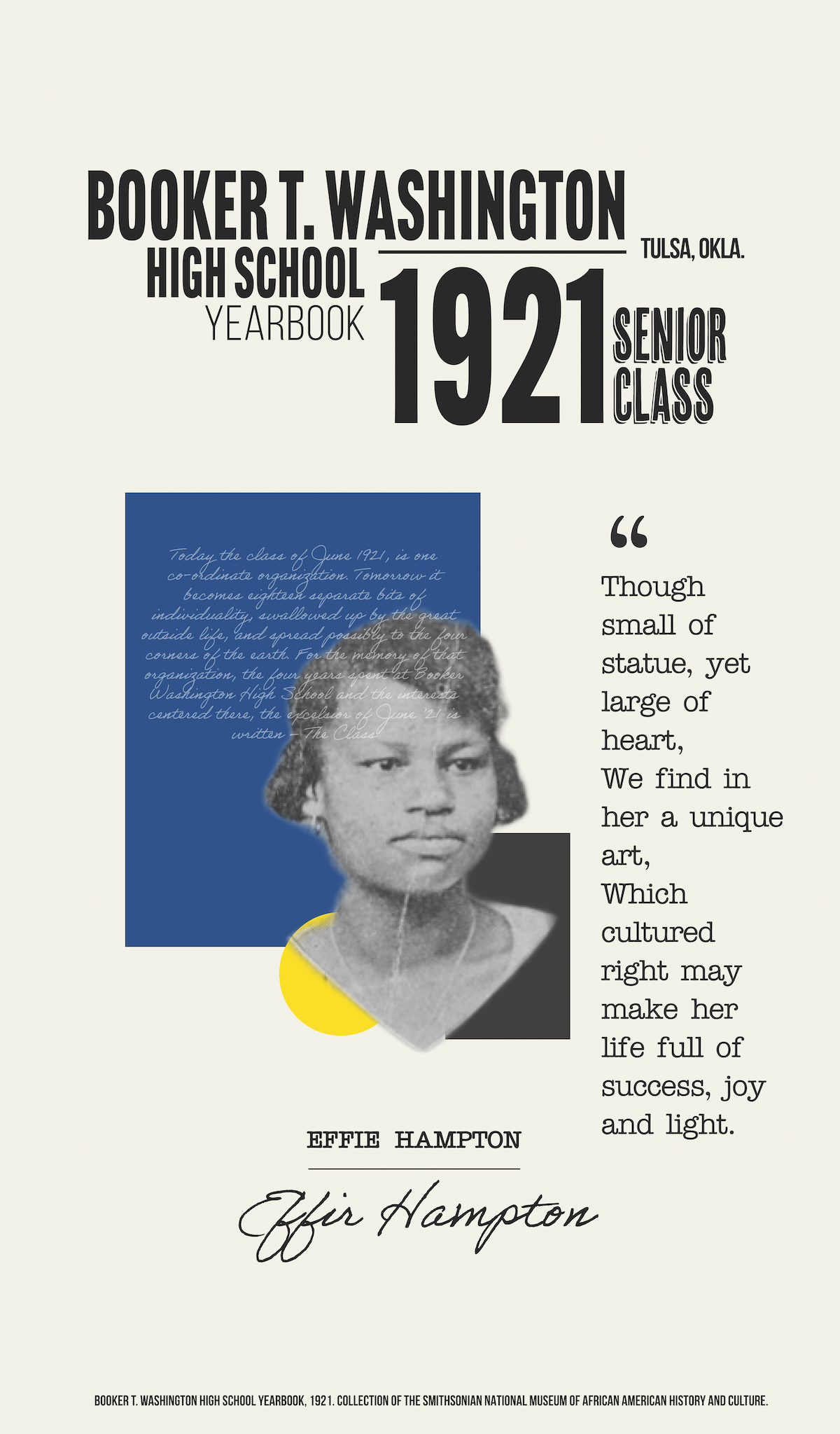

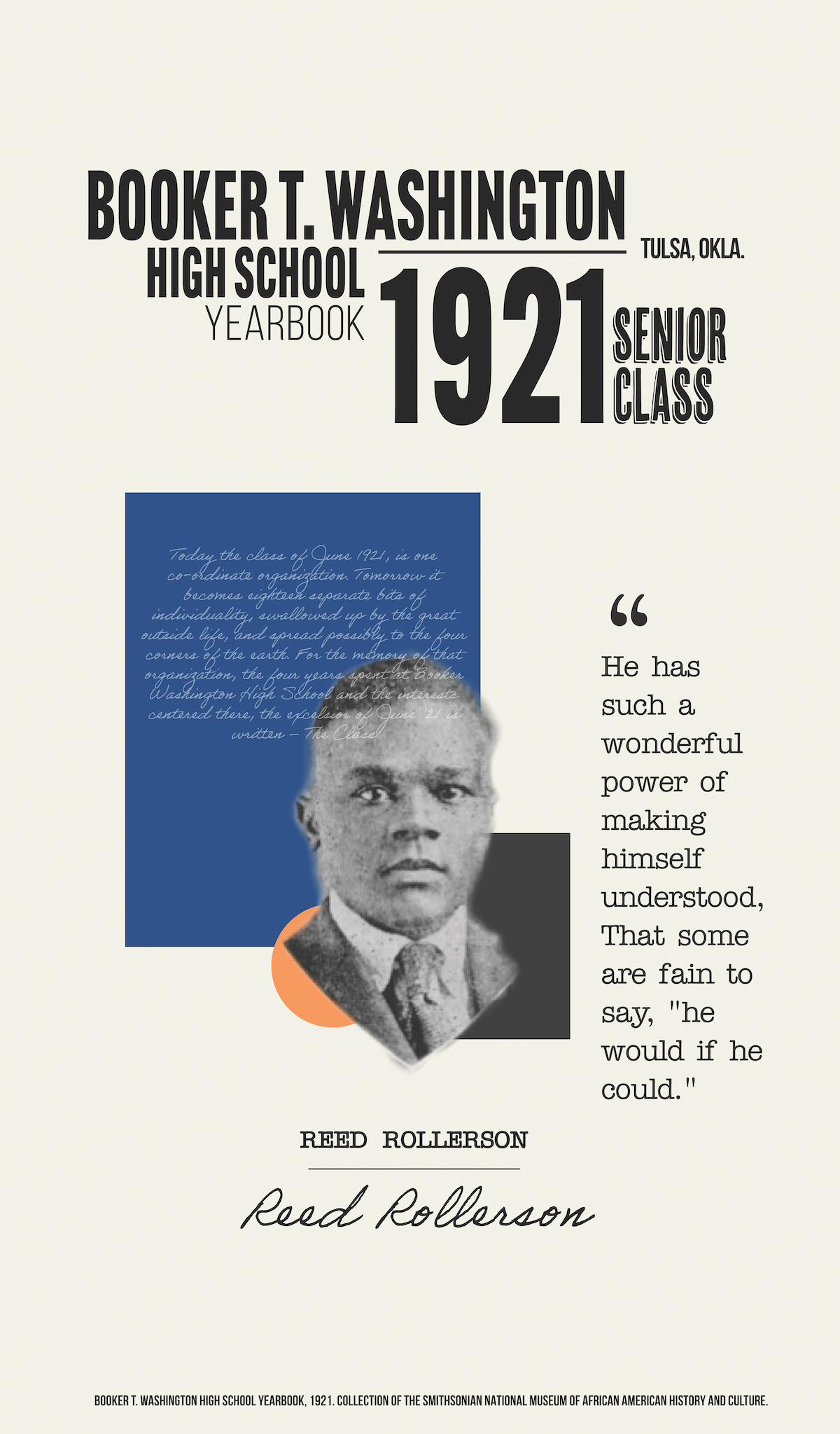

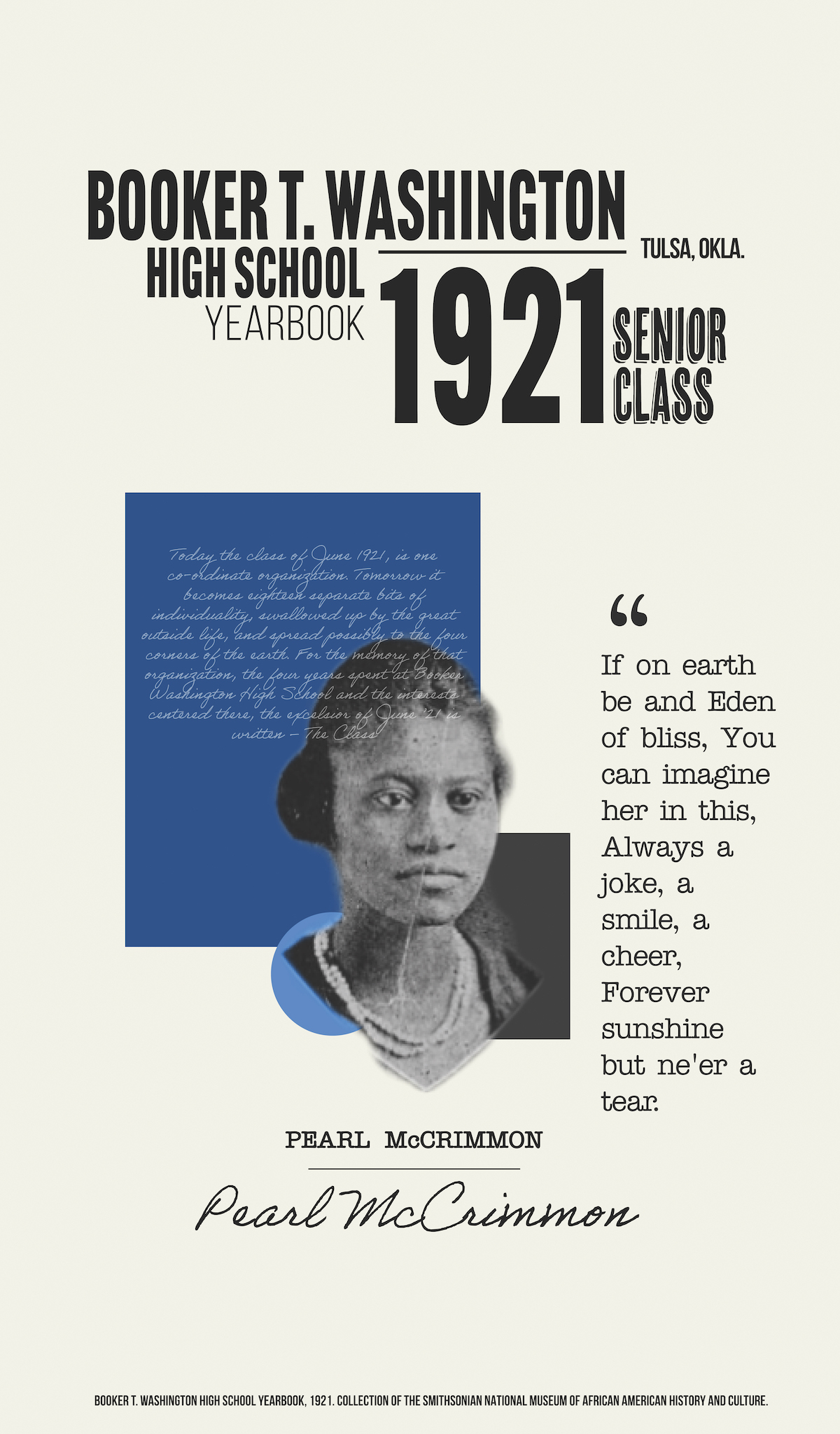

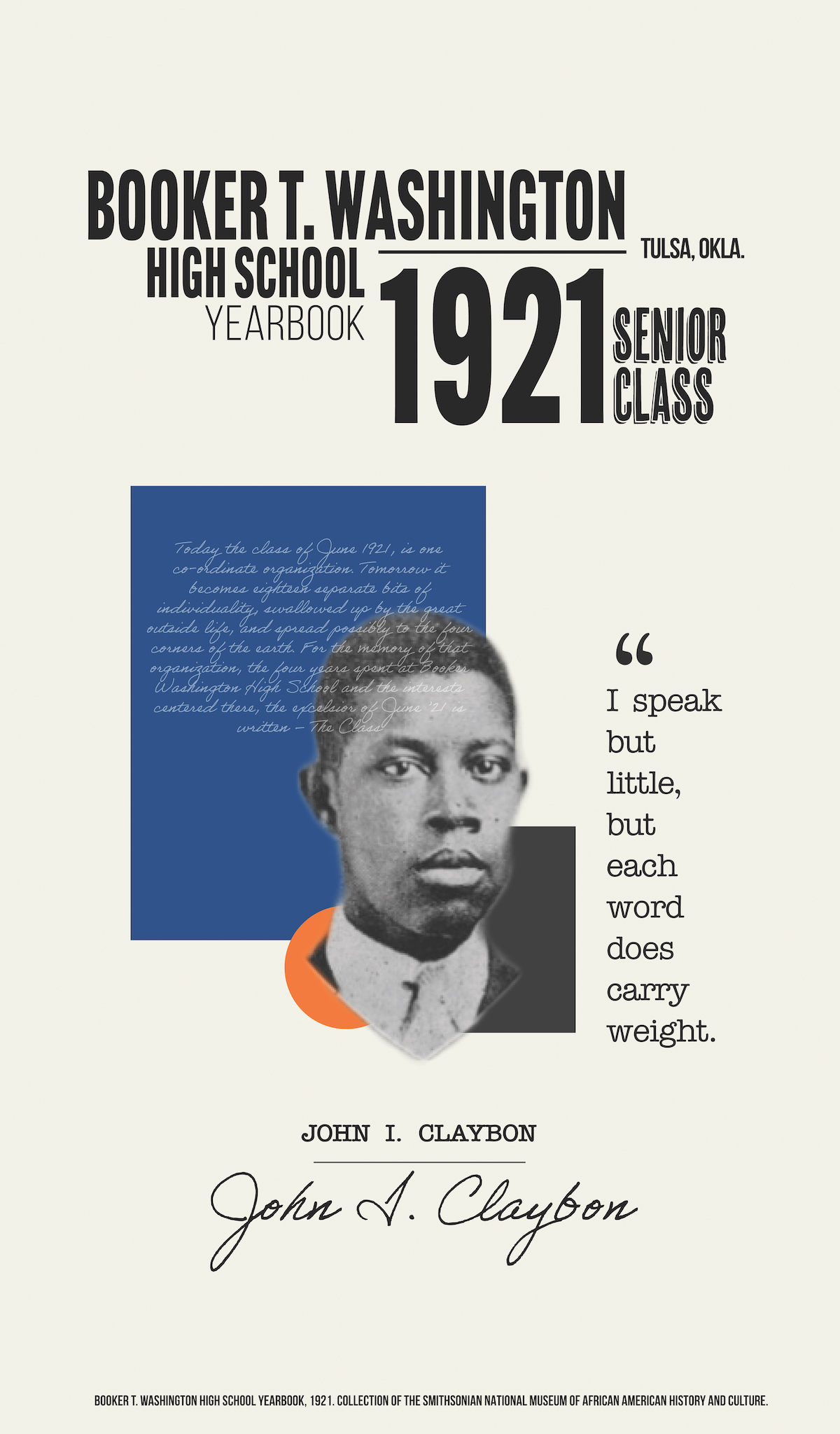

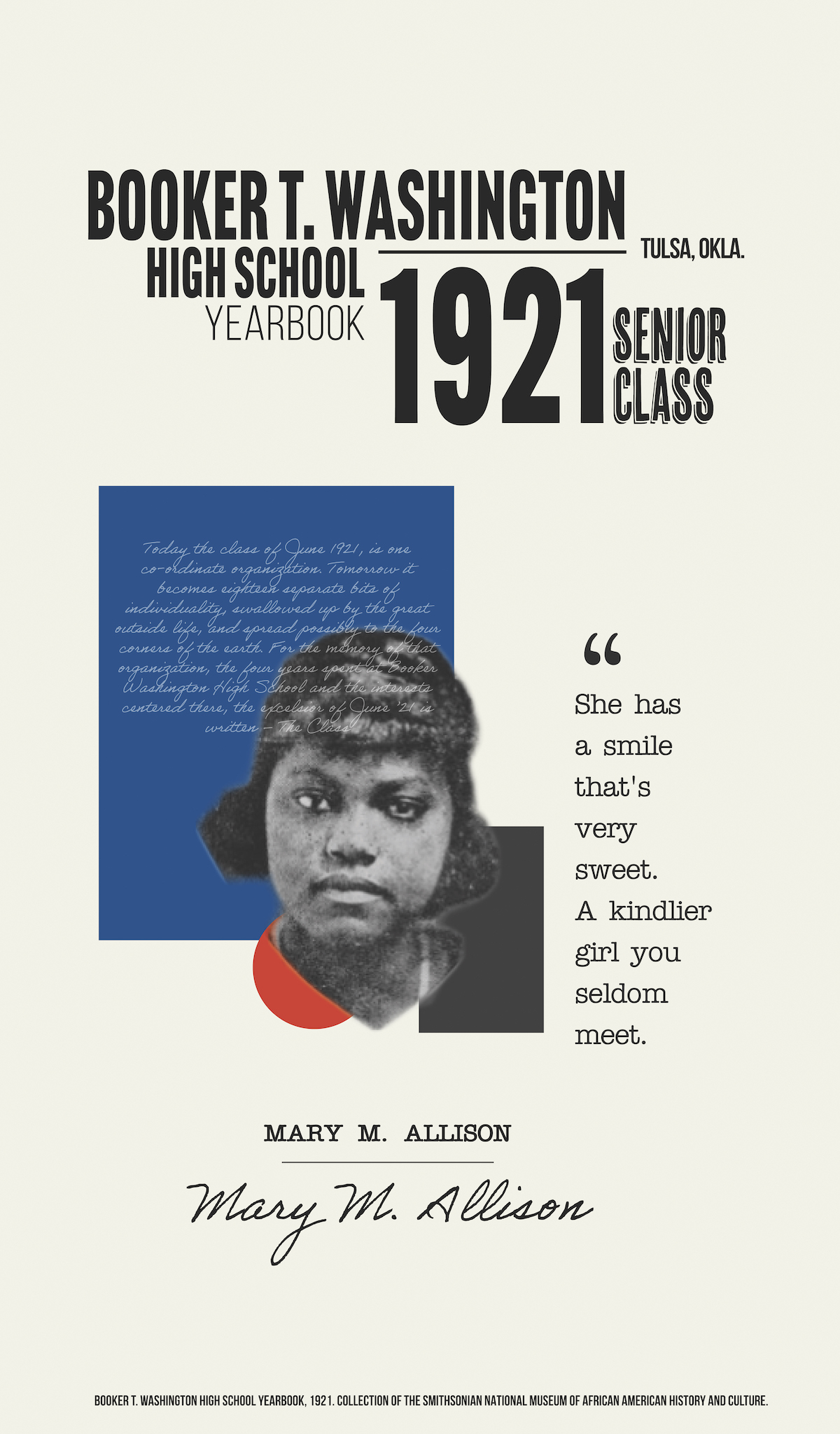

Other Booker T. Washington High School 1921 graduates were equal representations of a community that fully invested in young Black children. John I. Claybon, Mary M. Allison, Pearl McCrimmon, Reed Rollerson, Amanda Robinson, Esther Mae Loupe, Phineas W. Thompson, Celestine Z. Hodnett, Effie Hampton, Ora Lee Young, Janniva Brown, Dora Hogan, Bennie Tolbert, Beatrice Johns, Edward Goodwin and Beatrice Pratt. They were pure Tulsa, in every aspect, profoundly curious and well-educated.

The future BTW graduates were poised to begin a life of service within their communities, build upon the Black Wall Street legacy of entrepreneurship, pursue higher education goals and fight to secure the civic and economic freedoms denied millions of Black Americans during this time.

On Sunday, May 29th, days before the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, racially segregated congregations gathered to worship. Churches were filled with Black Tulsan parents and guardians of the soon-to-be graduates, the communities that celebrated the students’ success, and who leaned upon their faith in praise and for strength throughout the Jim Crow era.

Hymn and testimony, no doubt, passed beyond the walls of historic places of worship like Methodist Episcopal Church (est. 1887), the African Methodist Episcopal Church (est. 1905), the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (est. 1905), the Paradise Baptist Church (est. 1912), the Metropolitan Baptist Church, the Union Baptist Church and the Seventh Day Adventist Church.

Faith, as professed by white Oklahomans at the time, embraced the same marks of orthodoxy, edifices, gospels, hymnals and other representations including The Ten Commandments.

And yet, the stark contrasts in practice, specifically the legal regard for all human life, could not have been be more apparent to the BTW graduates of 1921. Or to the graduates of today.

The Gospels, with which most orthodoxies were aligned in Oklahoma, were objectively not applicable to Black Tulsans. Segregation, lynchings and mass murder were the justified responses to perceived encroachment and entitlement. No Black Tulsan man, woman or child was deserving of dignity, as represented in the state’s constitution, yet faith, Christianity, was regarded as the foundation upon which all were governed.

BTW graduates of 1921 were subject to both the legal cruelty of the state and a demand to accept that faith, a faith unlike their own, was the state’s moral foundation upon which life was governed, without objection.

That ugly history is repeating itself this year, as the State Superintended of Public Instruction, Ryan Walters, with his self-styled moral clarity, and a platform from which historic rhetoric is often spewed, announced that all Oklahoma schools must provide Judeo Christian Biblical doctrine.

A humble prayer before segregation and suffrage

Black Tulsans, parents of the 1921 BTW seniors, were well-aware of threats to their freedoms for more than a decade prior to the accomplishments of their children.

Racial segregation in the Christian State of Oklahoma during the late 19th century, inclusive of education, was well established and supported by legal precedent. Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision upholding racial segregation under the guise of “separate but equal” legal doctrine, was sufficient justification for Oklahoma’s poorly resourced and funded schools.

Primary education, after the Land Run of 1889, was usually available on a subscription basis, mission or tribal. Of the three models, subscription was the most common. Parents paid approximately a dollar per child each month for teacher compensation, supplies and a location.

Oklahoma statehood, the quest for a sovereign state, was long sought by settlers and professed Christians generations earlier. The advancement of statehood culminated in U.S. legislative action in 1906, when the U.S. House of Representatives introduced bill H.R. 12707, which would soon enable the formation of the state of Oklahoma.

Of concern to then U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt was the inclusion of any text in the new state’s constitution that would “limit or impair the rights of person or property pertaining to the Indians of said Territories” and that the governing document “make no distinction in civil or political rights on account of race or color.”

Satisfied that proponents of statehood would act in good faith, Roosevelt signed the proclamation turning Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory into the 46th U.S. state on November 16, 1907.

On December 2, 1907, approximately one month after Roosevelt’s executive approval, Oklahoma’s first legislative session commenced in Guthrie. After a prayer by Reverend H. A. Tucker, legislators earnestly crafted Senate Bill One, known as the “Coach Law”, legalizing the racial segregation of passengers on railway coaches.

The Christian State of Oklahoma, in the years that followed, would not be satisfied by the enactment of racial segregation. A statutory physical separation in public spaces, from the Negro, possessed insufficient calm or comfort for Oklahomans in the early century. Should they, the Negroes, seek to secure representation through civic engagement, threats against “the good Christian people of Oklahoma” would arise.

On August 2, 1910, with settled conscience and upon a professed moral Christian foundation, Oklahomans approved State Question 17, a petition restricting voter participation. Codified by the Voter Registration Act of 1910, the constitutional amendment would in effect deny Black Oklahomans civic engagement. “No person shall be registered as an elector of this State or be allowed to vote in any election held herein, unless he be able to read and write any section of the Constitution of the State of Oklahoma.” An exception, of course was granted to “all those who were permitted to vote on January 1, 1866, just after the Civil War ended, white Oklahomans.

The exclusion from the core practice and tenet of a republic, civic participation, would block Black Oklahomans’ ability to effect a future wherein they take an active role in governance. In accordance with the practice, just as the state’s first legislative session began in 1907, a prayer was offered to the body, undoubtably an expression of gratitude for the power wielded.

The application of Oklahoma’s “Grandfather Clause”, suffrage, was first tested by election officials Frank Guinn and J. J. Beal on Nov. 10, 1910, when eight Black Oklahomans were deemed ineligible to vote based upon the recent state constitutional amendment.

With assured moral and legal standing, state courts rejected the efforts of the Black residents.

Ultimately, Guinn & Beal v. United States became a legal challenge addressed by the U.S. Supreme Court, whose justices unanimously determined that the Oklahoma constitutional amendment violated the U.S. Constitution’s 15th Amendment protections against racial suffrage. The Jun. 21, 1915, decision possessed limited impact against racial suffrage, as the Christian State of Oklahoma would later implement new restrictions targeting its Black residents.

BTW 1921 graduates, just six years earlier, completed their elementary school education within the sanctity of institutions led by Black Tulsans invested in their futures, absent a freedom of choice, and commanded by Christian State constitutional provisions.

“God Almighty has drawn the color line in indelible ink.”

The gospel, so framed by generations of white clergy throughout the Christian State of Oklahoma’s early history, served to righteously bolster the convictions of the faithful, while securing a narrow and darkened space within which racial prejudice and injustice could survive.

Sanctuary rafters were filled with songs of praise and worship prior to Oklahoma statehood in 1907.

Baptists missionary efforts from the mid 19th through the early 20th centuries helped shape the landscape of faith in Indian Territory. Of historic significance is the work of Issac McCoy, a Baptist missionary, surveyor, and advocate of Indian Removal. McCoy’s objective, as a Baptist Missionary, was the conversion of American Natives to Christianity.

The Baptist Missionary’s vision for an increasingly Christian state populous would be realized in September of 1832, with the establishment of the first Baptist congregation in the Creek Nation, Muscogee Baptist Church.

The rapid growth in Oklahoma’s population following the Land Run of 1889 proved fertile ground for churches and charitable organizations to convert souls while providing much-needed services. Such contributions would lead to the establishment of new hospitals, colleges and academies, of which Bacone College (1880) and Oklahoma Baptist University (1910) remain.

Oklahoma’s southern and eastern borders, shared with Texas and Arkansas respectively, were gateways for the expansion of Southern Baptists, given the embrace of the denomination prior to statehood.

By 1921, Oklahoma’s population had grown to approximately two million, an increase of more than 22 percent since 1910. Tulsa, the second largest city, had a population of more than 72,000. The historic Greenwood District of Tulsa, home of renowned Black Wall Street, hosted a population of approximately 11K.

The 1921 BTW seniors lived within the borders of communities marginally protected from the threats of lynching by white Oklahomans. From 1885 to1930, an estimated 147 lynchings were recorded in Oklahoma, according to survey data compiled by the Tuskegee Institute, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and various scholars. The research undertaken also highlights dozens of lynchings were likely “unrecorded.”

No aspiring BTW graduate could have imagined the breadth of murder and destruction that laid waste to thousands of homes, a dozen churches, five hotels, 31 restaurants, four drug stores, eight doctor’s offices, more than two dozen grocery stores, and the Black public library by day’s end, June 1st.

The white mob, consisting of local Tulsans, city officials, law enforcement and community leaders, would commit to the murders of innocent Black men, women and children, numbering upwards of 1,000 residents.

The weeks that followed the historic act of domestic terror would prove to be fertile ground for local media and Christian leaders who represented the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre as an act for whom accountability rested with “agitators” and those who possessed little regard for God’s natural order of race.

Born in Spartanburg, South Carolina, on May 19, 1869, and educated at Wofford College (Spartanburg, South Carolina), Bishop Edwin DuBose Mouzon was most notably a Methodist clergyman, educator, and author of the late 19th century.

The southern native son, Mouzon, would soon take center stage after The Massacre, denouncing “social equality” and instructing white Christians to “give our colored friends to understand that there will never be anything like social equality in America.”

God’s natural order, according to Mouzon, was the separation of the races, and that any violation of that natural order would yield conflict, strife and hatred. Mouzon’s embrace of the “natural order” was further qualified by quoting “brilliant writer” Bishop E. E. Hoss, who established that “God Almighty has drawn the color line in indelible ink.”

The July 14, 1921, edition of the Christian Advocate introduced Mouzon’s published sermon as one of “intrinsic interest and value,” offered by a contributor “whose position, character and attainments give him a place of leadership.”

“Colored people”, Black Oklahomans of 1921, presumably lacked an ability to establish and be guided by a sound moral foundation, given Mouzon’s “constructive suggestions”, which he believed were “all in the light of the teachings of Jesus.”

“We must require a higher moral standard of these colored people…”, Mouzon demanded, foreshadowing an explanation of the perceived lacking. The published sermon then leaned upon a statement by an unnamed “colored bishop” who opined that “colored people are naturally imitative,” requiring white Christians to provide a model for morality.

For the eighteen BTW 1921 graduates, their parents, guardians, massacre survivors and surrounding Black communities, blame rested firmly upon their shoulders. Christian leaders, and by extension their congregations, were morally blameless for their actions, whether they fired upon innocent Black Tulsans on May 31st or June 1st, or stood quietly while watching slain children draw their last breath.

The Christian State of Oklahoma, as represented by Mouzon, was the victim in 1921, owing to a failure of not sufficiently educating, instructing, or guiding “colored people” to find grace in segregation, economic oppression and fear.

BTW 1921 graduates were well advised by Mouzon and the Christian State of Oklahoma to “know their place” in society, and that any effort to effect the spirit of the nation’s professed commitment to freedom would be regarded as an affront to God’s natural order.

The Christian Advocate, a periodical representing the state’s moral conscience, published what may be objectively perceived as contempt for Black Tulsans whose insolence was the cause of their slaughter.

The admonishment to BTW 1921 graduates was that although the Christian State of Oklahoma professed a faith in God, and that they are the children of The Creator, His mercy was not applicable to them.

The façade of faith

“Yes, I violently abused my spouse throughout the greater duration of our marriage, but haven’t harmed her this month, therefore I am a good Christian husband.”

THE PSEUDO MORALIST

One would respectfully assume that an educator, specifically a professional charged with providing instruction to high school students about the history of the world or specific regions, would be a source for objective perspectives.

The history teacher would first offer a comprehensive scope of a topic, context related to the period, and perhaps juxtaposition.

Should an Oklahoma high school history teacher field an inquiry about the scope of the slaughter from May 31st through June 1st in 1921 Tulsa, their response would include the centuries-long history of enslaved Africans, the de jure segregation of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, lynchings, threats of murder and the muted voices of moralists who ultimately walked the streets of the Historic Greenwood District “hunting niggers.”

An ahistorical response, nuanced with the intent of upholding the myth of the Christian State of Oklahoma by regarding a recorded history of atrocities as isolated events, would resemble an explanation once offered by Ryan Walters, the Oklahoma State Superintendent of Instruction. “Let’s not tie it to the skin color and say that the skin color determined that”, Walters stated in response to a question related to critical race theory and the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, during a July 2023 public forum in Norman, Okla.

“I believe that this is the greatest country in the history of the world… That doesn’t mean there weren’t mistakes made.”

RYAN WALTERS, Public Forum, Norman Public Library Central, July 6, 2023

Such nuances, persistent attempts to minimize generations of sin, and reductions of import, empower the believer of the Christian state to regard history as a tool by which morality may be cleverly defined.

As the Ten Commandments hung from the walls of churches, schools and homes throughout Oklahoma during the mid-19th century, it is instructive to recall that approximately 60,000 indigenous tribes (Five Civilized Tribes) were forcibly removed from their native lands southeast, ethnically cleansed by the U.S. government, marches to Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma).

The Choctaw, in 1831, were the first nation to be removed from native lands. The depths of cruelty experienced was noted by French philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville, who observed:

“It was then the middle of winter, and the cold was unusually severe; the snow had frozen hard upon the ground, and the river was drifting huge masses of ice. The Indians had their families with them, and they brought in their train the wounded and the sick, with children newly born and old men upon the verge of death. They possessed neither tents nor wagons, but only their arms and some provisions. I saw them embark to pass the mighty river, and never will that solemn spectacle fade from my remembrance. No cry, no sob, was heard among the assembled crowd; all were silent.”

ALEXIS DE TOCQUEVILLE, Democracy in America, 1835

The children of Greenwood, and BTW High School 1921 graduates, just over one-hundred years late, would share the same prayer as their murderers the night before. BTW graduates would rest assured that their regard for humanity was at least modestly shared by white Tulsans beyond the borders of Greenwood.

And why shouldn’t they?

The god of most Oklahomans presumably dwelled deep within the souls of most. Yes, the state’s history of genocide was well-known, but no threat greater than lynching and random violence was beyond the horizon.

Thoughts of mass murder were likely unimaginable.

And after all, Oklahoma was a Christian state.

The myth of the Christian state requires indemnification, absolution from sin, genocide, and mass murder, placing such acts aside, viewed as exceptions, not the foundation upon which churches now stand and roads cover.

The façade of faith is the goal.

And it is this façade, this myth, that survives by leaning upon the symbols of aspired goodness to hide the evidence of atrocity.