LOCAL & STATE

Deon Osborne

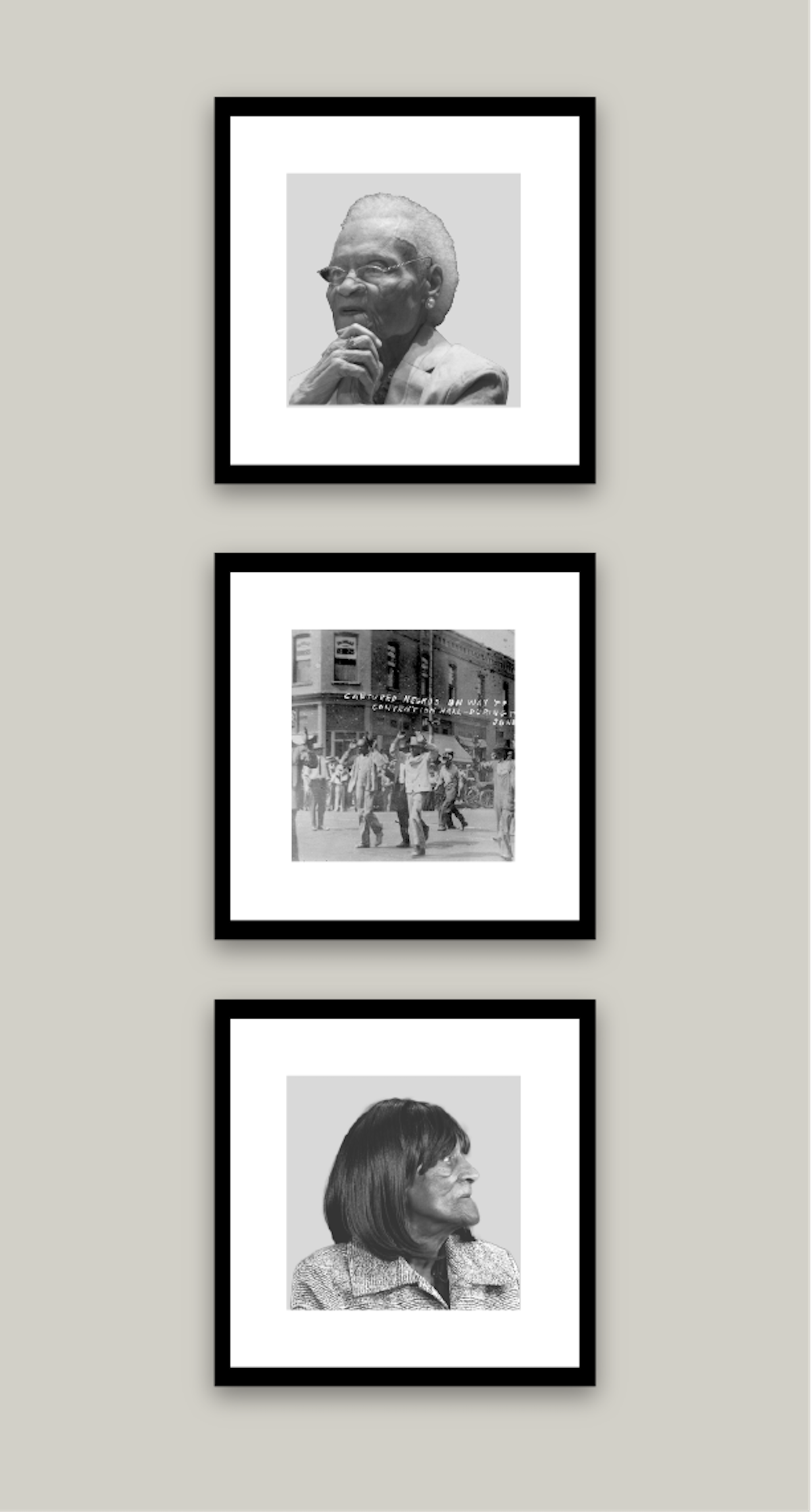

(TOP) Viola Ford Fletcher and (BOTTOM) Lessie Benningfield Randle, 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Survivors. Ilustration, The Oklahoma Eagle

During the 100th anniversary of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, Viola Ford Fletcher’s voice didn’t crack while seated before the U.S. House of Representatives, describing the violence of the white mob in her childhood community of Greenwood, the Tulsa, Oklahoma district, known as Black Wall Street.

“I still see Black men being shot, Black bodies lying in the street. I still smell smoke and see fire,” Fletcher told the U.S. House Judiciary Subcommittee in May 19, 2021.

Nearly three years later, on the warm spring afternoon of April 2, 2024, 109-year-old Tulsa massacre survivors Fletcher and Lessie Benningfield Randle, gazed up at the nine justices of the Oklahoma Supreme Court for the first time.

Fletcher and Randle are the last known living survivors of the government-sanctioned racial domestic terror attack after Fletcher’s younger brother, 102-year-old World War veteran Hughes Van Ellis, passed away in October 2023.

“Many have come before us who have knocked and banged on the courthouse doors only to be turned around or never let through the door,” Randle and Fletcher said in a joint statement to reporters ahead of the hearing.

In the hands of the chief justice, vice-chief-justice, and seven other associate justices’ lies the power to revive their historic case after Tulsa County District Judge Caroline Wall dismissed their claims in July 2023.

In a nation that has failed to apply equal justice and reparations to Black Americans and in a state that has denied responsibility for its role in perpetuating the destruction of an historic Black community, trust in the legal system remains low.

Yet, survivors of The Massacre have appeared at one court hearing after another, urging the world not to let Oklahoma bury their story. In a series of interviews with The Oklahoma Eagle, descendants, community leaders, and researchers expressed a determination to keep the story of Greenwood and their fight for justice alive.

“We’re talking about the most documented massacre in U.S. history.”

A native Tulsan, Dreisen Heath has dedicated much of her life to researching and consulting on the issue of reparations, both locally and nationally.

She was drawn to the work following a series of high-profile police killings, including the killing of unarmed Terence Crutcher in Tulsa in 2016. Researching how police brutality impacts Black communities led her to find a connecting thread between the harms from the 1921 attack on Greenwood and ongoing disparities today.

Despite Greenwood’s revival immediately after the destruction, attorneys for the survivors argue the impacts from the massacre, urban renewal, police brutality, and other issues reflect ongoing harms today.

In 2020, Heath published a Human Rights Watch report, which asserted the government is obligated by international law to provide reparations to massacre survivors and their families.

“Victims of gross violations of human rights, like the Tulsa Race Massacre, should receive full and effective reparations that are proportional to the gravity of the violation and the harm suffered,” the report stated.

During Tuesday’s hearing, several justices expressed confusion about why Tulsa County dismissed the case without allowing it to proceed to discovery and trial.

When Oklahoma Solicitor General Garry Gaskins argued the survivors didn’t meet the qualifications to seek a remedy for their injuries, Justice Noma Gurich gave a scathing response.

“How can there be any question that these plaintiffs have not been especially injured? I mean, did the military attack other neighborhoods in 1921,” Justice Gurich asked.

The vocal response drew a positive surprise from members of the community and their supporters inside the courtroom. Still, it remains unclear whether that pushback will evolve into a complete revival of their case.

“The Oklahoma Supreme Court should allow the case to go to trial and further discovery. We’re talking about the most documented massacre in U. S. history,” Heath told The Oklahoma Eagle.

“So, not only did the state commission a task force to investigate the massacre. We also have the most photographic evidence from the massacre that was then used by some of the white perpetrators to further dehumanize the Greenwood community by selling remnants of the massacre and the destruction as postcards,” Heath added.

The state of Oklahoma has refused to take action on decades-old recommendations for reparations found in the 2001 state-commissioned report. Heath’s Human Rights Watch report drew attention in Tulsa, but city councilors hesitated to approve a local commission to study reparations proposals.

The lack of action and the state’s denial of culpability represent a stark contrast from historical records.

“Gov. (James Brooks Ayers) Robertson declared martial law, and National Guard troops were deployed in Tulsa. Guardsmen assisted firemen in putting out fires, took African Americans out of the hands of vigilantes, and imprisoned all Black Tulsans not already interned. Over 6,000 people were held at the Convention Hall and the Fairgrounds, some for as long as eight days,” the Tulsa Historical Society recounts.

“Jim Crow, jealousy, white supremacy, and land lust all played roles in leading up to the destruction and loss of life on May 31 and June 1, 1921.”

These days, Heath travels across the country advising other communities seeking to move forward on justice and accountability for Black Americans. Dozens of local communities have moved forward on forming task forces, launching studies, advancing proposals, or contributing funding reparation plans in recent years, the most action on reparations since Union General William T. Sherman’s 1865 Special Field Orders No. 15., authorizing the redistribution of land to freed Blacks living in Confederate states.

On the federal level, Heath helped rally the votes needed to get H.R.40 onto the U.S. House floor for the first time in over 30 years. H.R. 40, first proposed by the late Rep. John Conyers, would establish a national commission to study reparations for descendants of enslaved people.

More recently, Heath worked with Congresswoman Cori Bush, the first Black woman to represent Missouri in the U.S. House of Representatives, to file a $14 trillion reparations bill last year.

Federal action on reparations remains at a snail’s pace as calls for justice grow louder.

“The lack of action is the story in and of itself. And there’s got to be more public pressure to get what we are owed,” Heath told The Oklahoma Eagle.

“This can be handled in the courts.”

Tuesday’s court hearing before the Oklahoma Supreme Court represents a legal crossroads for the Greenwood community and survivors of one of the worst instances of racial terror on U.S. soil. The court’s chief justice twice acknowledged confusion about why the case was dismissed without a trial, but that doesn’t necessarily indicate how the majority of justices will vote.

A lawmaker weighs in on the case

There is no timeline for a decision, but that is not stopping St. Rep. Regina Goodwin (D-73) from taking action. As a descendant of survivors in the Republican super-majority-controlled Oklahoma Legislature, Goodwin is no stranger to being one voice among a mob of opposition.

Unapologetic in her determination, Goodwin filed legislation to provide a victim’s compensation fund for the community ravaged by the government-sanctioned massacre. While much of her proposals have faced steep odds among her ultra-conservative colleagues, Goodwin’s bill to expand scholarships for descendants of the massacre has gained traction.

One of the recommendations from the state’s 2001 “Race Riot” report called for reparations in the form of college scholarships. However, during an interim study at the Oklahoma State Capitol in October 2023, Goodwin brought in experts to explain how the state’s scholarship fund for descendants has failed to support more than a few students.

Rep. Kevin West (D-54), the Republican chair of the General Government Committee, listened quietly during the interim study.

Following the hearing, he was asked whether he would push his colleagues to revamp the scholarship program.

“I would be open to it,” he told The Black Wall Street Times.

At Tuesday’s hearing in front of the Oklahoma Supreme Court on April 2, Goodwin listened as attorneys for the city of Tulsa, Tulsa County, and the state of Oklahoma denied any role in the destruction of Greenwood or the ownership of land in the community today.

“It’s despicable that you would have senior citizens and having to drag them into court, only to then suggest that they’re not quite sure of the harm that was done, not quite sure of the homes that were burned and the lives that were lost, how that is injurious,” Rep. Goodwin told The Oklahoma Eagle after the hearing.

“It is ridiculous in many ways, but it’s also part and parcel of what we’ve been seeing for a century-plus. So those mouthpieces, that mindset is the same mindset that we had back in 1921,” she added.

While the defendants continue to argue that the Oklahoma Legislature, not the courts, should decide reparations for Greenwood survivors, Goodwin rejects that argument.

“They know good and well this can be handled in the courts. It can be handled with this Supreme Court. It could’ve been handled with [Tulsa County] Judge Wall. So the bottom line is either folks are gonna do right, or they’re not.”

Moving forward, Goodwin has helped North Peoria Church of Christ secure a federal grant to study the cost of removing the portion of I-244 that cuts directly through Black Wall Street.

Constructed by the grandfather of Tulsa’s current anti-reparations Mayor G.T. Bynum, a descendant of survivors, is overseeing an effort to reclaim land for the benefit of a community once known as the most wealthy Black neighborhood in the nation.

“The bottom line is we want justice to be served for the folks that deserve it,” she said.

“Making sure this (harm to a people) will never happen again.”

For years, Tulsa County District Judge Wall’s slow-moving in the case raised fears that the court system of Oklahoma was waiting for survivors to die, to run out the clock on justice metaphorically.

In June 2023, Viola Ford Fletcher became the oldest living person to release a memoir titled “Don’t Let Them Bury My Story.”

Those fears became heightened after the passing of Fletcher’s younger brother, Hughes Van Ellis, at 102 years old in October.

A noted author’s perspective

For journalist and author of “Built From the Fire” Victor Luckerson, the defense’s arguments against bringing the case to trial reflect the same arguments used in 1921.

At one point, Oklahoma Solicitor General Gaskins argued that any National Guard members who attacked or killed Black residents of Greenwood were acting outside the scope of their employment and, therefore, the state shouldn’t be held liable, the news organization NonDoc reported.

“That was actually the specific argument that was made to the Oklahoma Supreme Court in the 1920s,” Luckerson told The Oklahoma Eagle.

For half a decade, Luckerson, formerly a journalist with Time Magazine and the The New York Times, entrenched himself in Greenwood and members of the community as he researched his book.

Unlike other books on the massacre, Luckerson focused on each generation of Greenwood and the government structures that impacted them in the 1920s, ‘30s, ‘40s’ ‘50s, ‘60s, and beyond.

“If that’s the legal standard, I think it’s a bad one because it absolves these bad actors, who have governmental power, of any kind of responsibility. That was interesting to me. What I had assumed was a very archaic interpretation of the law was actually revised wholesale 100 years later,” Luckerson said.

The state’s argument against reparations drew parallels to arguments made directly after the massacre, during a time when attorneys, judges, and city officials proudly signed their names on Ku Klux Klan rosters, according to documents housed at the University of Tulsa.

In 1923, the Klan controlled so much of the state that then-Governor John Calloway Walton declared martial law in an effort to drive out the KKK amid a flurry of lynchings. The Oklahoma Legislature, full of Klan members at the time, swiftly impeached him for his efforts to combat white supremacy, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Since Justice for Greenwood attorney Damario Solomon-Simmons first filed the historic state public nuisance case for survivors of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre in September 2020, Tulsa County District Judge Caroline Wall’s perspective about the case has been shrouded in mystery.

Yet during oral arguments on April 2, Oklahoma Supreme Court justices made their thoughts known.

“When I went to high school, I knew about the Trail of Tears…but Greenwood was never mentioned,” Justice Yvonne Kauger told the courtroom from the bench. “So, I think regardless of what happens you’re all to be commended for making sure that will never happen again, that it will be in the history books.”

Deon Osborne is an Oklahoma Eagle contributing writer who has covered the story of the survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre and their legal case for three years. He writes about the intersection of race, politics and justice.