SPORTS

Randy Hopkins

1921 Booker T. Washington, High School Hornets Football Team Illustration, The Oklahoma Eagle

In the fall of 1921, students began returning to Tulsa, Oklahoma’s Booker T. Washington High School, one of the few Greenwood structures to survive the Tulsa Race Massacre. The arrival of students also meant, then as now, that high school football would soon follow. In honor of Black History Month, this is the story of the 1921 Tulsa Booker T. Washington High School Hornets football season, a season played in the shadow of ruins.

The Hornets’ 1921 season marked the birth of “modern” football at the school in that it was the first year that the eligibility requirements of the Oklahoma High School Athletic Association were followed. While teams had been fielded since 1918, non-students, including teachers, had been allowed to play in the less formal games.

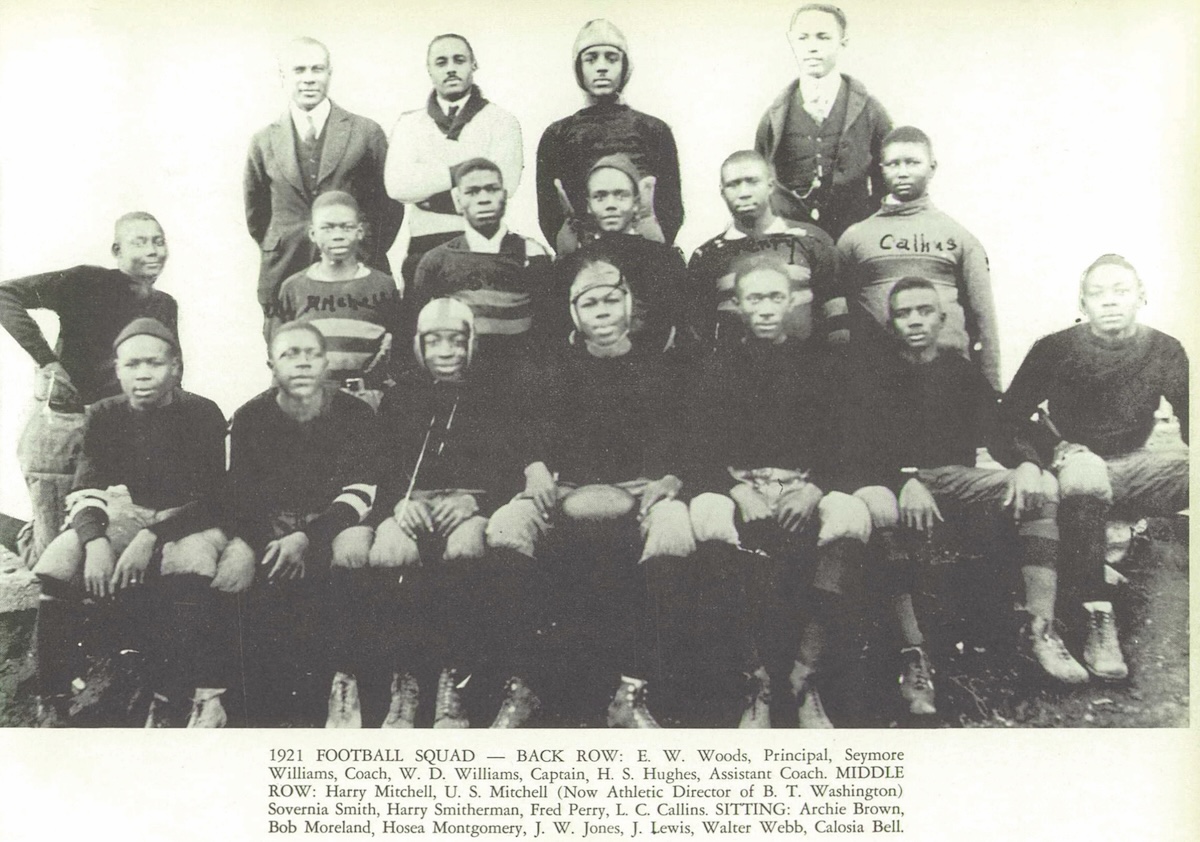

Booker T’s 1921 season was also notable for the return of J. W. (James) Jones. Jones is pictured in the middle of the front row on the team photo holding a football. Jones is commonly believed to have been none other than the historical character “Diamond Dick” Rowland, whose arrest created a trigger for the Massacre. Rowland resided in the Tulsa County Jail until Sept. 28, when charges against him were dropped, just in time to get back to school for his junior year.1

Surviving news coverage of the Hornets’ 1921 season is sparse, with little focus on individual players. The Tulsa Star was no longer around and the copies of The Oklahoma Eagle from 1921 have not survived. White newspapers did not report on the “colored” high school football teams, save for the Claremore Progress, which covered the Claremore Lincoln Giants.

Hornets Tight Budget

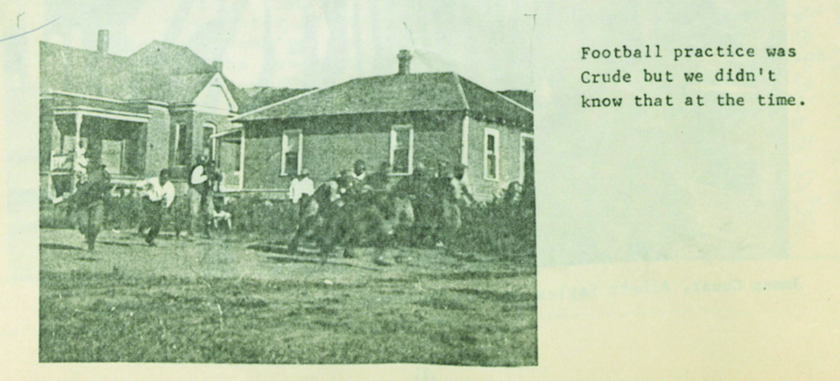

According to Heywood W. James, sports editor of Oklahoma City’s The Black Dispatch, it cost $750 to equip a team for the season, not counting balls, advertising, and injury supplies. The money was hard to come by and the teams relied on financing by school teachers. Even a big city team like Oklahoma City Douglass lacked adequate practice grounds. In the case of the Hornets, the school provided only jerseys and pants. There were no shoulder pads and a cobbler tacked cleats onto ankle-boots for the shoes. Only three Tulsa players could afford helmets, one of whom was Jones.

In contrast, Tulsa’s other high school, located south of the railroad tracks, funded five football teams. In addition to the Tulsa Central High varsity, there was a team for each of the school’s classes, freshmen to senior. All five traveled and played away games. The goal was to funnel experienced players into future varsity teams. The plan soon paid dividends, as the Central High Braves claimed the 1922 White state football championship.

Back then, Black high schools were only permitted to compete against other Black schools. The same segregation, however, did not exist in the crowds that attended games. The Claremore Progress reported that, “many white people attended in addition to the colored population.”

The Black Dispatch made a point of inviting “all Oklahoma City” to the opening game of the season between the Oklahoma City Douglass Trojans and Tulsa Booker T. Washington. The game was played on Thurs., Oct. 20 at Oklahoma City’s minor league baseball stadium, Western League Park. Douglass High School was permitted to play its games at the baseball field “when the whites don’t want it.” The Hornets won 24-0, “outplaying Douglas in every stage of the game.”

Hornets Punish Okmulgee Team

The following Thurs., Oct. 27, brought the return of organized football to Greenwood. The Hornets celebrated the occasion by drubbing the visiting Okmulgee Dunbar Tigers 96-0. The Hornets’ B-team took over early and “Little Mitchell,” Tulsa’s one hundred pound back-up quarterback, plunged through the line for the final score. The most spectacular play of the day was an 85-yard kickoff return by Elmer Pitts. It must have been an exciting day for a community that had suffered so much.

The Hornets played a second home game on Thurs., Nov. 4 against the more formidable Giants of Claremore Lincoln. The 1963 Booker T. yearbook claims a 14-0 Hornets victory, but The Black Dispatch and the Claremore Progress reported the Hornets prevailing by 14-7. Tulsa scored the winning touchdown in the last three minutes of play, having been set up on the Claremore 10-yard line by a 30-yard pass interference penalty.

The defending state champions, the Red Devils of Nowata Lincoln, fell to the Hornets 7-6, though the date, location, and details of the game are presently unknown.

Armed with an undefeated record, the Hornets prepared for the final game of the season — a Thanksgiving Day trip to face the Muskogee Manual Bulldogs. The teams had last played on Thanksgiving Day 1920, when the Bulldogs broke a late scoreless tie with a blocked punt in the Hornets’ end zone, winning 7-0.

Reports from The Black Dispatch

Muskogee’s 1921 record is unknown, but the Bulldogs had beaten Claremore by a much wider margin than had Tulsa.2 The Black Dispatch described the Tulsa-Muskogee tilt as a “classic for the supremacy of the Negro high schools of Oklahoma.”

The Black Dispatch also provided a scintillating description of the game and its controversial outcome. Leaving no doubt as to its opinion of the affair, the Dispatch titled its article “Muskogee Attempts to Beat Tulsa Through Newspapers, But It Was Tulsa’s Game All The Way.” The Dispatch decried the “effort of certain individuals in Muskogee to obtain the championship by means fair or foul,” an effort “surpassed in crookedness only by a like attempt to twist newspaper reports so as conceal the facts from the public.” The reference to the Muskogee Cimeter newspaper was clear. Unfortunately, the pertinent issue of the Muskogee Cimeter has not surfaced.

There was no attendance reported, but the game must have been packed, with fans crowding up against the playing field. Muskogee won the toss, but their offense stalled. The Bulldogs made no first downs in the first quarter. On Tulsa’s opening possession, the Hornets sliced through the Muskogee defense, only to be foiled by a fumble inside Muskogee’s 10-yard line. The Bulldogs punted out of danger and Tulsa took over on the 50-yard line. The first quarter ended 0-0.

Fake plays and end runs carried Tulsa to Muskogee’s eight-yard line, when the first controversial call occurred. The head referee, a man named Kenyon, halted the game to warn fans to leave the end zone. He then inexplicably moved the ball back to the Muskogee 10-yard line. The Hornets could only gain eight and a half yards before turning the ball over on downs. The referee had “clearly robbed Tulsa of a touchdown” in the words of The Black Dispatch.

Disaster struck the Hornets’ next possession, when a Bulldog defender returned an interception for 56 yards for a touchdown. The extra point failed and the half ended Tulsa 0, Muskogee 6. During the second quarter the head linesman, a man named White, was reported to have “became active” and penalized Tulsa three times for off-sides.

The Hornets “came back in the third quarter with a vengeance,” marching down the field for a touchdown. The successful extra point made it Tulsa 7, Muskogee 6.

The Bulldogs appeared to turn the ball over on downs on their next possession, only to be saved by another offsides call by White. Muskogee “seemed to take on new life” from this favorable turn and the third quarter ended with the home team on the Hornets’ 40-yard line.

Four more plays by the Bulldogs failed to gain a first down, but White assessed another offsides, placing the ball at the Tulsa 27. Muskogee could only gain seven yards on the next four plays, but White threw yet another fourth-down off-sides flag. The ball was now at the Hornets’ 15-yard line, first down. This is how The Black Dispatch described White’s behavior:

Head linesman White MAY HAVE meant to be fair but his fairness was terribly one-sided or his eyesight very poor. When an official waits until a play has been completed, then walks back to the line and compares the distance gained with the distance required, and then assesses a penalty, something is wrong. Why Mr. White failed to call off-sides plays on Muskogee is unknown—especially when we remember that they were constantly off-side on one of their shift plays—but rather than contribute it to unfairness we will say he is subject to fits of blindness. (emphasis in the original).

At this point, Hornet head coach Seymour Williams “attempted to report to the head linesman so that he might take the matter up with the referee. This could not be done and he was warned to leave the field.”

Unrest on the field

Pandemonium suddenly broke loose, as the crowd stormed onto the playing field. The field was said to be “so thick with people that bees could not have swarmed thicker.” The bees left no room for the Hornets. In response to the chaos, Williams withdrew his players from the field, rather than let them be engulfed in another mob. The officials ordered the Hornets to return, but made no attempt to clear the field of play. Instead, head referee Kenyon focused on his watch and, after exactly three minutes, declared the game forfeit to Muskogee, 1-0.

The Black Dispatch quoted the offending Muskogee Cimeter article as reporting only that “the Tulsa bunch became incensed at a penalty…and took their team from the game.” The Dispatch castigated the paper for failing to mention the pitch invasion, which had driven the visiting team from the field and which created “the utter impossibility of playing football.”

Protests and petitions to replay the game with different officials ensued, but Muskogee was unmoved. The Hornets claimed a 7-6 victory and Muskogee no doubt claimed it 1-0. According to The Oklahoman, the 1921 Black High School football championship was instead bestowed on defending champion Nowata Lincoln, the Red Devils’ defeat at the Hornets’ hands notwithstanding.

Tulsa Booker T. Washington only had to wait one year to gain its first undisputed state football championship. Fulfilling Seymour Williams’ promise to take on all high school competitors, the Hornets’ season expanded to 12 games. The 1922 Hornets won them all.3 Twenty-seven more state football titles followed, nine of those after the integration of Oklahoma high school football in 1955.

No team roster for the 1922 state championship season has yet surfaced, but it would have been James W. Jones’ senior year.

Randy Hopkins, an historian and Oklahoma Native is an occasional contributor to The Oklahoma Eagle