Red butcher block paper covered hundreds of books as the 10th-grade students entered their English classroom in Norman, on the first day of school classes on Aug. 19.

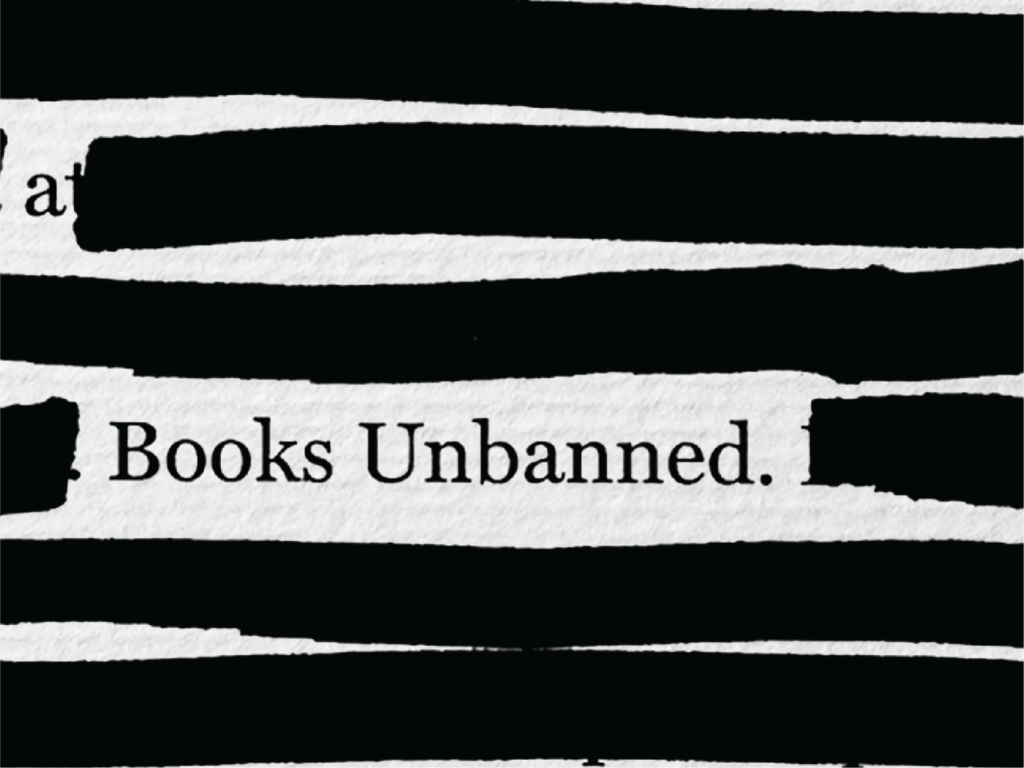

Scrolled over the covered books was a message inscribed by English teacher Summer Boismier, who had a clear point to make, “Books the State Doesn’t Want You to Read,” and a QR code to access “Unbanned Books” from the Brooklyn Public Library in New York.

This was the eight-year veteran teacher’s way of resisting book banning and the Norman Public Schools’ effort to make her sort through and remove those books.

It was also her way, she said, of introducing herself as an advocate for “politics of inclusion” and a profound response to the controversial House Bill 1775, legislation restricting Oklahoma’s public school educators from teaching on the topics of ethnicity and gender issues that “one race or sex is inherently superior to another race or sex.”

Any violation of the law had serious legal consequences, including suspension and revocation of teaching licenses and certificates.

But unfortunately, Boismier, 34, would shortly find no other choice but to resign as one of her student’s parent’s complaint caused Norman school officials to cower.

Baseless pornography complaint

By the end of the first day of school, that one parent, Laney Dicksion, had complained to school officials that Boismier violated H.B. 1775. Dicksion said that the QR code Boismier provided linked to the Brooklyn Public Library on that same butcher block paper. Linking to the New York City Public Library, she said she found a list of pornographic content.

The link actually was to the American Library Association’s website and its April 4 press release titled, “Top 10 Most Challenged Books’ list and a new campaign to fight book bans.”

The top banned book was “Queer Gender: A Memoir,” by Maia Kobabe.

Dicksion told Oklahoma City’s Fox 25 that after reading aloud the book, “Queer Gender,” she deemed it “pornographic material” and accused Boismier, 34, of violating state law. The graphic novel book is both an award-winning American Library Association, and its most challenged book in 2021.

The hard copy of the book Dicksion was waving around for the television interview was not obtained from either Boismier or was it an e-book obtained using the QR code she provided for her students.

“The woman (Boismier) has access to children and to minors,” Dicksion told the Oklahoma City television station. “No one should be allowed to disseminate this to children, much less a teacher in our public school system.”

Wes Moody, Norman Public School’s director of communications, said Dicksion verbally claimed access to this book violated H.B. 1775.

So, as public school districts statewide attempt to police themselves, H.B. 1775 has empowered many ultra-right, professed evangelical-parents, a Republican legislature, teachers, and staff to become vigilante watchdogs who are digging their noses to review curriculum, staff training materials, classroom instructions and teaching methods to determine if the law is being violated.

Boismier’s account

Boismier’s story and the fallout has garnered international attention both from admirers and critics. The days that followed have been filled with death threats, accusations of being a pedophile, the online release of her home address and learning that the Oklahoma Secretary of Education, Ryan Walters, has requested that her teaching certificate be stripped away.

She told the Oklahoma Eagle that she has become exasperated at Oklahoma Republican politicians, who had made decisions on public education that served their partisan interests at the expense of the interests of public schools and the thousands of teachers, administrators, staff, elected school board members have invested in Oklahoma’s 509 school districts.

She said this new wave of laws has been decades in the making as the state made a “slow motion consistent effort to de-professionalize the teaching profession.”

She said the most recent examples by GOP lawmakers include ignoring the advice of health officials for students and staff to wear masks and get vaccinated during the coronavirus pandemic, passing H.B. 1775 restricting race and gender instruction, and then “imposing harsh sanctions without due process on Tulsa and Mustang school districts” for unwittingly violating the law. Boismier said it is “very important to realize who is at the center of the story, emphasizing it is “not her but the safety and support of our public schools.”

She noted how Norman Public Schools exacerbated her frustration by requiring each teacher, as a consequence of H.B. 1775, to review all of the books in their respective classroom libraries in search of topics of “sexual/suggestive nature” and “racial sensitivity.” Boismier pointed out that NPS already had a review process for introducing new books and a written procedure for challenging them. And that teachers “have never been required to cull their personal libraries for offensive content.”

So, in her mind, this was a subjective, redundant requirement that was “pointless” in light of the “vague and confusing law.” And further that it was “absurd to put the onus on the teachers” to do this, she added.

Brooklyn Public Library Books Unbanned. Photo Brooklyn Public Library

The Boismier plan

So, she devised a plan whose actions would not violate H.B. 1775 and would comply with school district directives. For example, she said she knew there was no provision in H.B. 1775 dealing with pornography, explicit sexual content or remote, electronic access to off-premises books.

Further, there was no evidence Boismier included the book Dicksion claimed was pornographic as part of her “instructional material” in her classroom teaching.

And the district had given her a written option instead of reviewing each book “to pause student access” until the review was complete.

So, Boismier said she would follow the law and followed school district directives, but let her viewpoint be known. That viewpoint was that H.B. 1775 is a “fear-based” law resonating harmfully in the classroom, and she said she “refused to waste her time pretending otherwise for partisan hacks.”

Then she added her First Amendment statement about what she thought about book banning by inscribing “Books the State Doesn’t Want You to Read” and provided a QR code link to a New York Public library’s “Unbanned Books” books section.

She also said this would be a good way of introducing “who I am” to her students as was traditionally done on the first day of school: give them access to information that “would help them validate their own identity,” and jump-start a lesson in “critical thinking,” which was core to her English curriculum.

That first day, the weekend and Monday

Contrary to later claims made by Norman Public School officials, Boismier told the Eagle she only spent a few minutes at the end of each class explaining why the books were covered, and why she had done so. She said her students throughout the classes she had that day expressed “no negative opinions or feelings of discomfort.” She said she had many students thank her after class, then, and since, mainly for the message of “inclusiveness.”

She said a key tenant of educators’ “best practices” was to work with students and parents as “collaborators” in the learning process and that “fear-based” H.B. 1775 had quite the opposite effect, which she was trying to overcome.

At the end of the school day on Aug. 19, she was told to report to the district office at 8 a.m., Monday, Aug. 22, for unspecified reasons. Over the weekend, she was fraught with anxiety over how to prepare for the meeting.

She did not know whether to “take a lawyer with her or a union representative,” having had no disciplinary issue with the district prior to this. Ultimately, she emailed her principal seeking further explanation. When the principal could provide none, Boismier asked to postpone the meeting, until she knew what was going on and how to prepare. The principal agreed to that but said she would not be able to teach classes on Monday, her regular pay would be docked, and her “personal leave time” would be used to compensate her until the meeting was held. She told the Eagle this was “unfair” and equivalent to a suspension.

Thrown under the bus

When the Tuesday, Aug. 23, afternoon meeting occurred, she was told of the parent’s complaint about the QR code and link to “pornographic material.” Boismier told the Eagle that the weight of all this and the lack of district support prompted her to resign immediately.

Fearful of an H.B. 1775 complaint, Norman schools’ spokesman Moody later told the Eagle, referring to Boismier’s resignation, the matter “was resolved at this point unless there were further developments.”

The chilling effect of H.B. 1775 and the recent harsh sanctions imposed on Tulsa and Mustang school districts caused NPS to panic.

A statement Norman schools’ released almost immediately following Boismier’s resignation read, “The teacher had, during class time, made personal political statements and used the classroom to make a political display expressing those opinions… We have heard a great deal of concern from our educators and even parents about the consequences of HB 1775… This year we placed a renewed emphasis on teachers and staff reviewing classroom resources.”

The public reaction

Meanwhile, Boismier’s problems were far from over.

The days that followed would be filled with death threats, accusations of being a pedophile, the online release of her home address, and learning that the Oklahoma Education Secretary Walters had demanded that her teaching certificate be stripped away.

Boismier says the threats “ratcheted up” following the publication of Walter’s letter to the Oklahoma State Board of Education. In fact, the most severe threat followed, one that mirrored some of Walter’s words and caused her to file a police report.

The President of the Oklahoma Education Association, Katherine Bishop, responding to Walter’s threat to Boismier teaching certification, released this statement. “Instead of wasting his time creating a political spectacle, we ask he spend more resolving the real issues facing the students of Oklahoma, such as the growing educator shortage crisis and the broadening resource gaps created from the underfunding of our public schools who serve every child, not just some.”

However, Boismier said she would do it all over again.

She has not made plans for her next moves, but she summed up her resolve in one word, “Ready!”