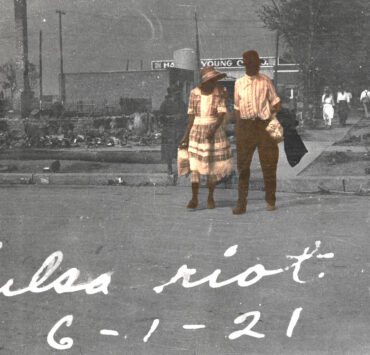

Mt. Zion Baptist Church loomed tall below Standpipe Hill in the Greenwood community. The year is 1921, and the congregation had just begun worshipping in their fresh, two-month-old building, according to the church’s website. Black riflemen stood in the belltower of the church to get a better angle of racist white gunmen approaching from the west, eyewitness reports the Oklahoma Historical Society show.

The white mob was able to overpower this defense with machine guns, which tore into the church’s brick exterior. Shortly after, arsonists lit Mt. Zion ablaze, and $92,000 worth of construction and years of fundraising was reversed into a steaming pile of rubble, according to the church’s website.

Many other churches in the community faced the same fate yet were determined to rebuild.

“It was like they didn’t take no for an answer. They didn’t take tragedy as a means to just say, “Hey, we’re going to stop living and we’re going to stop worshiping God,” said Freeman Culver III, Ph.D., president and CEO the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce. “They didn’t let that deter them from being children of God and servants in the community.”

Culver illustrated how, due to a lack of insurance claims, the churches did not receive much help from the city in order to rebuild. The community had to unite and work to build the city back together.

“During that particular time, African Americans, they didn’t always put the money in banks. They put them in peculiar places, like chimneys and ice boxes and different things, you know,” Culver said. “So, some of them had funds to rebuild.”

Out of about 13 churches that were burned, Mt. Zion is one of three that remains in the historic Black Wall Street area. After its destruction, the congregation gathered and worshipped under the Rev. J. H. Dotson in the charred basement of their former church, according to the church’s website.

“In 1952, Rev. Dotson and the members saw the fruits of their unwavering faith and belief come to completion with the dedication of the present building,” the website said.

Though their city was left in pieces 101 years ago, the Black community of Tulsa pulled themselves from the rubble to rebuild. The community was able to open 242 Black-owned and operated business by 1942, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

“I think the other thing that makes it unique is that it is an example of how a community can overcome when Black folks came to this area, they were told what you couldn’t do what you guys can, you’re on this side of the tracks. This is your area, but we showed that we can create our own success,” said Damali Wilson, who is executive director of operations for World Won Development. “I mean, we had Black doctors, lawyers, dentists, judges, airports, everything that we needed to be self-sufficient, was contained right there in Greenwood district before it was destroyed.”

A Resurgence

Culver explained how some white business owners had a closeted influence in the Historic Greenwood District’s resurgence.

“A lot of people don’t know this, but there was actually a lot of white proprietors that actually had land in Greenwood that was affected by the massacre in 1921,” Culver said. “Many of them, behind-the-scenes, worked with the Black community to help rebuild it.”

It was the community’s support for each other and the district that helped it rebuild.

“It just shows you know, the level of intelligence and the level of working together in the spirit of community that everybody had for each other because it took everybody circulating their dollars within that space in order for those businesses to be successful,” Wilson said.

The faith the community rebuilt after the massacre has become threatened once again, however, due to new industrial developments pushing Black culture and history out of Greenwood.

“So, I think that is also a concern that that is what’s happening here in our city, is that these plans and this development that’s coming is not for the people that are actually here in this community, it’s actually being made for people who live outside of our community to come in and take over and just erase everything that has been created or to rewrite the story in a way that does not honor the people who gave their lives for this area,” Wilson said.

The Tulsa Urban Renewal Authority’s plans for the Historic Greenwood District began as early as 1957, with the creation of the Interstate 244 expressway – or the 4-highway Inner Dispersal Loop, or IDL. According to the city observatory, “the construction of freeways was used to demolish, divide and isolate communities of color.”

Culver said it is unlikely for the highway to be removed despite its impact on the community.

A highway runs from through us

This year, the Biden administration has launched a $1 billion initiative, called Reconnecting Communities, to undo some of the damage caused nationwide by the construction of the interstate system. The massive highways were originally built to serve predominantly white suburban commuters, at the expense of Black and low-income neighborhoods in the city core.

The section of the I-244 expressway in the Historic Greenwood District was highlighted in the study as one 15 highway projects that should be removed. To make way for the expressway, about 3,000 homes and 500 businesses owned by African Americans were bulldozed.

U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg visited the community on Aug. 23, saying that it was important to pay attention to “not just what the massacre did but what highway policy did.”

“So, there is some hope but for many people, it is wishful thinking to think that the government is going to remove that highway when it’s been there for a while and people actually use it constantly,” Culver said “So, I think it kind of serves as a as a testament of urban renewal and at one time, the government did not respect our communities, didn’t care about our business community, didn’t care whether or not we were able to continue to spend in our businesses and growth. So, this is kind of like a Blackout. It won’t never go away.”

Community activist Kristi Williams explained how new buildings and industrialized spaces are sweeping out Black culture and Black neighborhoods by dividing the community.

“What you see happening in Greenwood today is a real-life Monopoly game,” said Williams, who chairs the Greater Tulsa African American Affairs Commission.

Culver identified that the money from these new developments is not truly benefitting those who need it most.

“A lot of times, when support, resources come to the area, it never filters down to actually help real people, real small businesses,” Culver said. “We need resources, and I think new developments are great but let’s take care of what we already have. Those new developments will just feed off of what we already have, you know, and just, you know, throwing money on the situation with new developments is not the answer. Let’s take care of what we already have historically. Let’s see that flourish, and then we can move on.”

A pillar remains

Mt. Zion still stands in Greenwood despite its destruction more than a century ago. The spirit of the community rebuilt it, and it now faces the looming developments threatening to tear it apart.

The church’s small but fiercely loyal congregation is a testament to survival and the strength of faith. Many of the current members are descendants of North Tulsans who were deacons, ushers and loyal members in the 1920s and ‘30s.

Brenda Jones, an usher, is a proud third generation Mount Zioner. The church honored her grandfather, James H. Woods, by enshrining his name in a cornerstone of the building. Woods was an active Mt. Zion member in the heralded era of Rev. Dotson.

“This church is a longstanding pillar of the North Tulsa community,” 77-year-old Jones told the Oklahoma Eagle. “It has never closed its doors. And as long as the leadership offers services, we will be here.”

About this project

The Oklahoma Eagle, in partnership with the University of Maryland Philip Merrill College of Journalism and the School of Journalism & Mass Communication University of Wisconsin-Madison, and the “On the Ground Reporting” project.

We have collaboratively instructed participating journalism students through the process of publishing stories that focus on community groups and issues in Tulsa and Oklahoma. The class was led by Maryland associate professor and Washington Post staff writer DeNeen Brown, an Oklahoma native, who teamed with Eagle editors M. David Goodwin and Gary Lee.

To read other stories in the student project, visit https://theokeagle.com/on-the-ground-reporting/