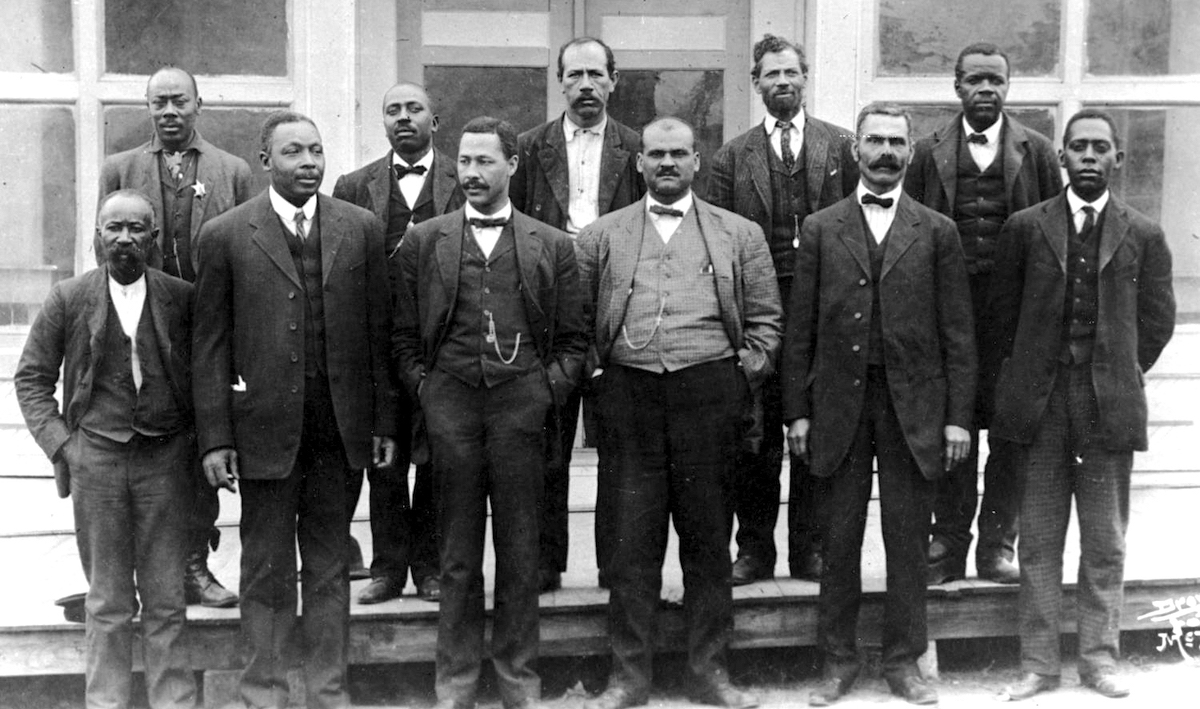

From 1865 to 1920, African Americans created more than 50 identifiable towns and settlements in the Indian Territory and after Oklahoma’s statehood in 1907. Today, only 13 such towns still survive: Boley, Brooksville, Clearview, Grayson, Langston, Lima, Red Bird, Rentiesville, Summit, Taft, Tatums, Tullahassee and Vernon. The largest – about 1,100 people – and most renowned is Boley in Okfuskee County. The oldest is Tullahassee in Wagoner County, which dates back to 1850 before being incorporated in 1902.

On Aug. 20, Oklahoma’s 13 remaining historically All-Black Towns convened a meeting at the Oklahoma History Center in Oklahoma City. The all-day conference allowed each city to share its rich histories, unique economic development, and town engagement and marketing strategies.

While the presenters did talk about their town’s founding, past and current population, many of the presentations were short on long-range planning, development strategies, and the sharing of best practices.

Except for Langston, the presentations offered little evidence of any strategic planning, strategy on sustainability or long-term resilience. Many of the presentation themes and challenges centered around failing infrastructure, the absence of capital improvements, a fleeing population and absentee landowners. Many of these towns still have not organized to the level of creating a city tax structure. They offer no municipal services. Some are accepting donations to pay their annual insurance.

We owe our ancestors more than this level of mediocrity.

A unique chapter in American history

These cities are far from their zenith and need complete strategic makeovers. In Booker T. Washington’s closing thesis in an article written in The Outlook in 1908, he suggested that the Negro struggle for liberation was a long struggle aimed and centered around morality, collective development and worth and freedom. Unfortunately, Booker T. Washington wouldn’t recognize this current iteration of All-Black Towns.

Today’s All-Black Towns of Oklahoma represent a unique chapter in American history. Historically, they are proxies for those ancestors who gained land in Indian Territory through tribal allotments. In 1906, The Muskogee Cimeter – the then 5-year-old weekly newspaper serving the area’s Black community – reported that about 20,000 Indian Territory Freedman accounted for about 3 million acres of land. Freedmen of the Five Tribes – Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole – had more land than the estimated 1 million acres controlled by about 1 million Black folks in Georgia. An estimated 8,000 Creek citizens, classified as Freedmen, held nearly 1,092,240 acres in 1907 during Oklahoma’s first year as a state.

The Reconstruction era (1863-1877) created an infectious movement of self-pride within these All-Black communities. However, it didn’t come without a penalty. The white power structure was unhappy with this newfound Negro liberation.

Oklahoma’s statehood strategically and politically changed those dynamics. On Dec. 2, 1907, the Oklahoma Legislature passed its first law – Senate Bill One or the coach law – which enforced racial segregation on the railway. Oklahoma’s Jim Crow laws was an evil extension of America’s separate and unequal system that remained the law of the land until the U.S. Supreme court declared it unconstitutional in 1952.

But in 1907, the impact of Oklahoma’s white supremacy, racism, brutality and leadership indifference – both federal and state indifference – led to an exodus of Blacks to Western states, Canada, and Mexico. Before Oklahoma’s statehood, most of the reported Indian Territory Lynchings occurred among non-African descendant communities. After statehood, most of the state’s lynchings were almost exclusively people of African descent. Some were murdered, and many were terrorized.

My very own Oklahoma ancestry mirrored this migration pattern during that period. Urbanization of major cities has also contributed to a decline of all rural communities, especially “All-” Black Town.

An unknown future

Should Oklahoma’s All-Black Towns still exist?

Not in this current iteration. If these towns are to thrive into this millennium, they need business models, partnerships, and collaborations with Urban Black Americans to ensure their survival. The All-Black Town of Oklahoma should collectively develop a strategic plan and footprint model that strategically and politically elevates their needs. These towns need a Marshall Plan if they are to survive.

Dr. Maurice O’Brian Franklin a direct descendant to some of Oklahoma’s current and extinct Oklahoma All-Black Towns. He is Creek and Chickasaw Freedman. Franklin attributes his activism and social justice commitment to the influences of mom, James Baldwin, Marcus Garvey, and his 4th great grandfather Buck Franklin, and cousin Dr. John Hope Franklin. Dr. Franklin lives in New York City, is a Navy veteran and is a native of Pauls Valley, Oklahoma.