‘Move The Negroes Out’: James Baldwin commenting on Urban Renewal in 1963.

By John Neal, For The Oklahoma Eagle

Gary Lee, Contributor

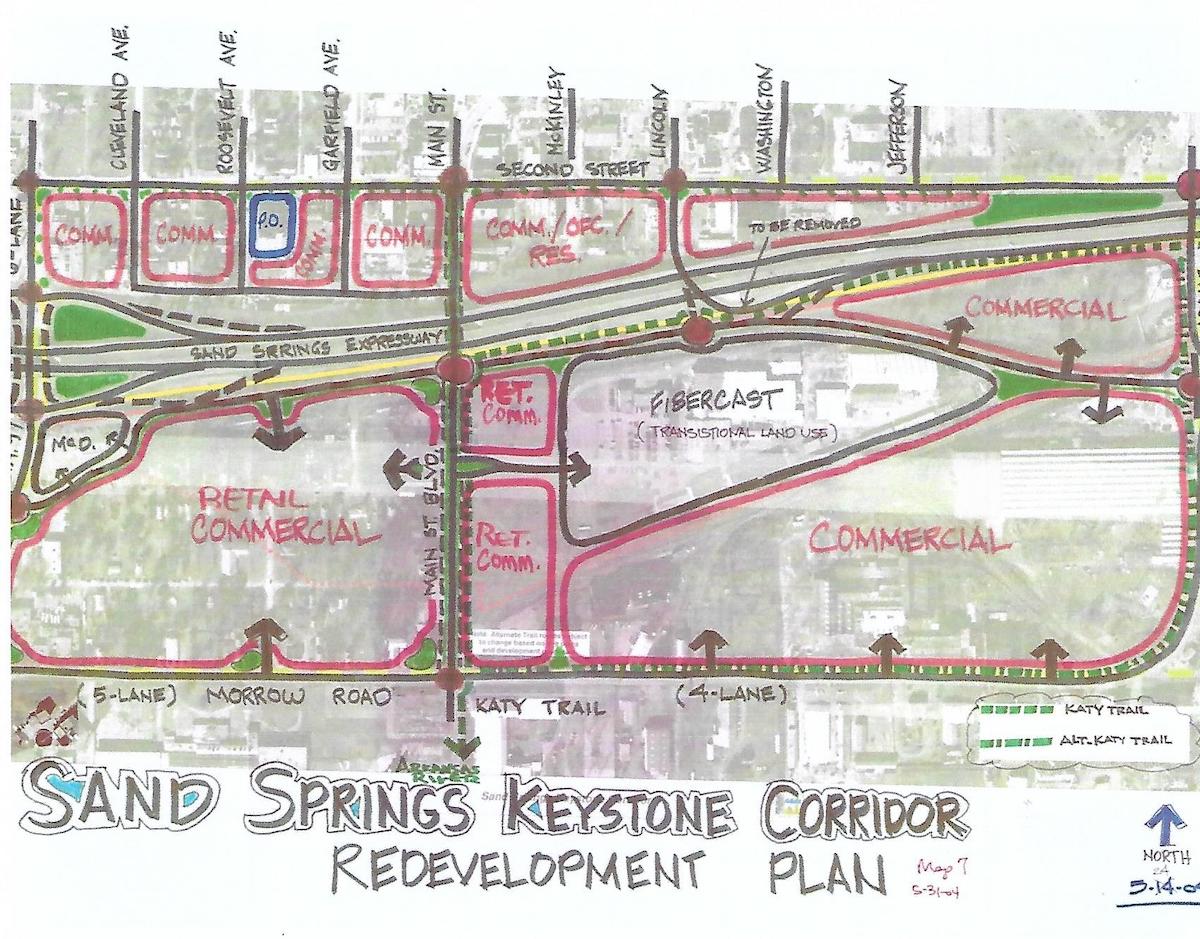

Sand Springs and Tulsa metropolitan officials introduced a plan in 2003-2004 for what would be called the “Urban Renewal” of Sand Springs. Their blueprint for the project ran over 94 pages. Still, it was ominously vague on specifics of what changes the officials had in mind. It was particularly short on details of proposals that would affect housing in the Black community.

A decade later, the officials had accomplished at least one of the primary goals of their mission. They had demolished Sand Spring’s most prominent Black community and replaced it with a retail and commercial district. Using the powers of urban renewal and both the threat and use of eminent domain condemnation, they dislocated the neighborhood’s Black residents. They then demolished their homes and two Black churches. They also wiped out the community’s longstanding education institution, Booker T. Washington School. It had been the place Black Sand Springs students had been educated during the era of segregation from 1912 until the mid-1960s.

This is the story of how a small group of Oklahoma officials, using plans clearly designed to deceive Blacks and other Sand Springs residents, successfully wiped out the century-old Black neighborhood of one of Tulsa’s most prominent suburbs.

Janice Ross, who was raised in the Black community of Sand Springs, decried the erasing of the neighborhood. Her roots in the area run deep: her parents graduated from Booker T. Washington High School in Sand Springs in 1933. “That was a loving community,” she said in an interview with the Oklahoma Eagle. “Between the school, the churches, and all of the neighbors, there was a lot of history there. Just to come in and wipe it out with no trace that it existed is just not right.”

David Rose concurred with Ross. In his youth, the North Tulsan lived off and on in the Black neighborhood of Sand Springs. His family, including great grandmother Maddy Cloud, grandmother Rosie Taylor and mother Ernestine Taylor Rose, were lifelong Sand Springs residents. “It was a well-regarded community,” he explained to the Eagle. “And they just walked in and got rid of it in a cloak of darkness.”

That cloak still obscures significant parts of the narrative of how the Black neighborhood was made to vanish. Irving Frank, a local Republican who was a senior INCOG official at the time, appears to have been one of the key architects of the plan. But in the Eagle’s review of the documents, few names appear of those who pushed the project through.

The Set-Up

The background of the plan seemed innocuous enough. In 2003, Tulsa community leaders wanted to build a sports arena. They devised a sales tax referendum. The proceeds were to be used to issue revenue bonds to construct the arena. Because the sales tax referendum would be countywide, Tulsa needed support from other municipalities in the county and their voting residents. To secure that support, they solicited projects to be added to the referendum from these governments.

In early 2003 Sand Springs submitted several projects. The largest was the “Keystone Corridor Redevelopment Project.” The various projects, spread across the region, were collectively referred to as Vision 2025.

The “Keystone Corridor” referenced the section of the Sand Springs Expressway that ran through Sand Springs from Tulsa to the Keystone Lake recreation area. Where this proposal originated is still unclear. But the Indian Nations Council of Governments (INCOG) developed, wrote, and presented the plan. INCOG was also the regional Municipal Planning Organization, and the Sand Springs municipal government was a member.

The roles of the Vision 2025 countywide leaders who selected the project and those of the INCOG planners were central to what transpired in Sand Springs. These leaders were mostly comprised of elected officials in Tulsa, Sand Springs and surrounding cities who were interested in pushing what they perceived to be the economic interests of the area.

Following the successful sales tax referendum, INCOG presented the project in early 2004 as the Sand Springs Keystone Corridor Redevelopment Plan, “Corridor Plan.”

This article draws extensively from the Corridor Plan document that was presented. There are several reasons:

- It is the document accessible to the public, setting forth what was proposed and was the document submitted to the Sand Springs Urban Renewal Authority, the City Planning Commission, and the City Council for consideration and approval.

- The Corridor Plan constituted an amendment to the Urban Renewal Plan governed by Oklahoma Statutes, which among other things, authorized the involuntary acquisition of real property and structures.

- It provided the legal, policy, and administrative context for everything that followed in Sand Springs concerning these events.

- The Corridor Plan states: “Prior to the vote, Sand Springs residents selected the Keystone Corridor project, which was included in Proposition 4 on the successful ballot.” It is difficult to understand what is meant by “Sand Springs residents selected” as there was no referendum on the project in Sand Springs.

Reading the fine print

And as to the project being “included” on the ballot, the ballot Proposition 4 text as voted on September 9, 2003 was as follows:

PROPOSITION NO. 4 (Capital Improvements/Community Enrichment)

“SHALL THE COUNTY OF TULSA, OKLAHOMA, BY ITS BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS LEVY AND COLLECT A SEVENTEEN AND ONE-HALF PERCENT (17.50%) OF ONE PERCENT (1.0%) SALES TAX FOR THE PURPOSE OF CAPITAL IMPROVEMENTS FOR COMMUNITY ENRICHMENT [EMPHASIS ADDED] WITHIN TULSA COUNTY, OKLAHOMA, AND/OR TO BE APPLIED OR PLEDGED TOWARD THE PAYMENT OF PRINCIPAL AND INTEREST ON ANY INDEBTEDNESS, INCLUDING REFUNDING INDEBTEDNESS INCURRED BY OR ON BEHALF OF TULSA COUNTY FOR SUCH PURPOSE, SUCH SALES TAX TO COMMENCE ON JANUARY 1, 2004 AND CONTINUING THEREAFTER TO JANUARY 1, 2017?”

FOR THE PROPOSITION-YES

AGAINST THE PROPOSITION-NOi

The Keystone Corridor Redevelopment project was not outlined in the Proposition. But $14.5 million in funding for the project was included under a vague reference to a number of projects described as “capital improvements for community enrichment”.

A casual reader of the plan is unlikely to immediately grasp the intended consequences the project would have on the Black residential areas.

“On September 9, 2003, the voters of Sand Springs and Tulsa County combined in approving the Vision 2025 plan and program to encourage economic development and growth in area cities and towns and Tulsa County,” the plan said in an opening paragraph. “The Sand Springs Vision 2025 Keystone Corridor Redevelopment project is the $14.5 million initiative to redevelop the Keystone Corridor.”

“The purpose of the Sand Springs Keystone Corridor Redevelopment Plan: 2025 (Corridor Plan) is to arrest the decline of an area in the central part of the City’s economic downtown area, assemble the land, implement a strategy for clearance, and promote redevelopment to make this area a central and positive focus of community growth and attraction- a point of destination for persons living within the Sand Springs market area, as well as a point of attraction and destination for persons from the larger metropolitan area and northwest Oklahoma.”

In this context, a reader could interpret “redevelopment” as something like the Cambridge Dictionary defined it: “The act or process of changing an area of a town by replacing old buildings, roads, etc., with new ones.” In Oklahoma statutes, “redevelopment” is used interchangeably with “urban renewal.”

The Target

As it turned out, the South Side Additions of Sand Springs were the principal target of the “redevelopment” initiative. Not coincidently, they also constituted the largest Black neighborhood in the city.

The Corridor Plan, and thus the extension of the area subject to urban renewal, encompassed this Black residential area.

To be clear, this neighborhood was just that – a residential area. It was not a “central part of the city’s economic downtown,” as the blueprint suggested.

Charles Page, Sand Springs’ town founder, ensured that the Black area was not central. In 1911, he platted Southside Additions – the area set aside for Blacks -to be separated from the white community by the Katy railroad tracks. It was literally on the other side of the tracks.

To be sure, over time, Sand Springs officials had allowed manufacturing, industrial, and later commercial businesses to surround and encroach into the neighborhood and diminished its size.

But the residences, churches, and schools were not part of the economic downtown. This distortion of facts and misleading statements riddle the Corridor Plan (urban renewal mechanism) and prevented neighborhood residents from fully knowing what was happening until it was too late.

Indeed, the stage was set for this as Sand Springs submitted this project in early 2003 for inclusion in the referendum by declaring this area “blighted.”

Before using the powers of urban renewal, a site must be declared blighted.

On March 24, 2003, the Sand Springs City Council adopted Resolution No.03-09. The resolution was achieved without fanfare or much publicity. But in an extraordinary move, it immensely increased the blighted area in Sand Springs subject to urban renewal and its powers. It increased the designated blighted area from approximately 26 acres, adding 454 more acres (including the 94 acres in the Corridor Plan). This vast swath of land constituted more than three percent of the entire city and more than double the size of the downtown business district. This was done months before the Tulsa County sales tax referendum and was a legal prerequisite for including the proposed redevelopment area in the revised urban renewal plan.

The Corridor Plan includes this Resolution but does not refer to the increased land this would be added to the Urban Renewal Area. The Resolution adds 454 acres, all said to be”… blighted areas and specifically a blighted area south of the downtown area… which constitutes a serious and growing menace, injurious and inimical to the public health, safety, morals, and welfare of the residents of the City of Sand Springs….”

It is doubtful that area’s residents knew that the Sand Springs Early Childhood Center, the three Black churches, McDonald’s, other businesses, ever knew they constituted such a serious threat to the City.

One can draw a straight line through the declaration of blight, submission of the project for the inclusion in the referendum, development of a Corridor Plan, and the subsequent exercise of the threat and use of condemnation under urban renewal (eminent domain) to the destruction of Sand Springs’ largest Black neighborhood community. As the Corridor Plan finally clarifies in Part II “The primary objectives of the Corridor Plan are…Remove substandard residential, commercial, and industrial buildings…Develop a new retail and commercial center for Sand Springs and the market area.”

The preservation and rehabilitation of the Black neighborhood was never an alternative, even though this could have been accomplished in several ways. The blight Resolution states, “salvable blight areas can be conserved and rehabilitated.” This mirrors the state’s authorizing language of “rehabilitation or conservation in an urban renewal area” and “carrying out plans for a program of voluntary and compulsory repair and rehabilitation of buildings and other improvements.”

Clearly, the legal and administrative framework existed in urban renewal to repair and rehabilitate the neighborhood as an alternative.

The Black neighborhood

The residents of what was called Area A, the first phase of the redevelopment plan, deserved special attention. Although the Corridor Plan does not mention it, they constituted by far the largest Black neighborhood in Sand Springs, including half of the city’s Black population.

Based on the Corridor Plan, there were 68 occupied residences in the area. The Corridor Plan failed to point out that by law, the “repair and rehabilitation of buildings or other improvements” was an alternative to “demolition and removal.”

The Plan does not subdivide the Estimated Finance Plan budget by area. But the acquisition, clearance, and relocation budget was a total of $9,425,000. Area A represents 27 percent of the total acreage. Part of the budget could have gone to repairing or rehabilitating these 68 occupied residences.

Mayme Crawford, whose family has been part of the Sand Springs Black community for generations, laments that the city did not try to restore and preserve some of the houses that Blacks called home. “A more careful, sensitive plan would have explored that option,” she said in an interview with the Eagle. Crawford, 81, graduated from Booker Washington in 1958, is an active leader of Sand Spring’s Black community.

Instead of rehabilitating homes, the Sand Springs officials behind the project decided to spend the money acquiring and demolishing these properties.

It is also noteworthy that 50 of the 68 occupied residences were rentals. Records show that a white landlord owned dozens of properties. Thus, a vast majority of the alleged blight in the residences was due to landlord neglect. That made them subject to “compulsory repair and rehabilitation” under the powers of the Urban Renewal Authority and property code enforcement by municipal officials. At a minimum, this could have been used as an adjunct tool, further stretching the funds set aside in the plan to be used for repair and rehabilitation.

But the municipal officials behind the Corridor Plan had goals other than preserving and rehabilitating Sand Spring’s Black neighborhood. Instead, they envisioned creating a commercial district.

The Corridor Plan, adopted after the ballot measure, makes no mention of “eminent domain.” That is the legal mechanism by a public legislative body to take private property involuntarily for a general-purpose. This power was automatically granted in Oklahoma State Statutes by adopting the Corridor Plan incorporating the 92 acres into the new Urban Renewal Area, having declared the entire area blighted the previous year. Nor does the Corridor Plan disclose that Sand Springs Development Authority (SSDA), acting as the Urban Renewal Authority, had bestowed upon it by these series of actions the power of “condemnation” of property. The phrase “eminent domain” is not stated or explained in the Corridor Plan. “Condemnation” appears only once — without context or explanation — on page 87 of the 94-page document.

Ironically, the section where the word “condemnation” appears is in the innocuously titled “City of Sand Springs Relocation Assistance Plan, Policies and Guidelines,” that the terms “eminent domain” and “condemnation” would later be used overtly against 14 parcels of property and threatened to be used in other cases.

ABOUT THIS SERIES

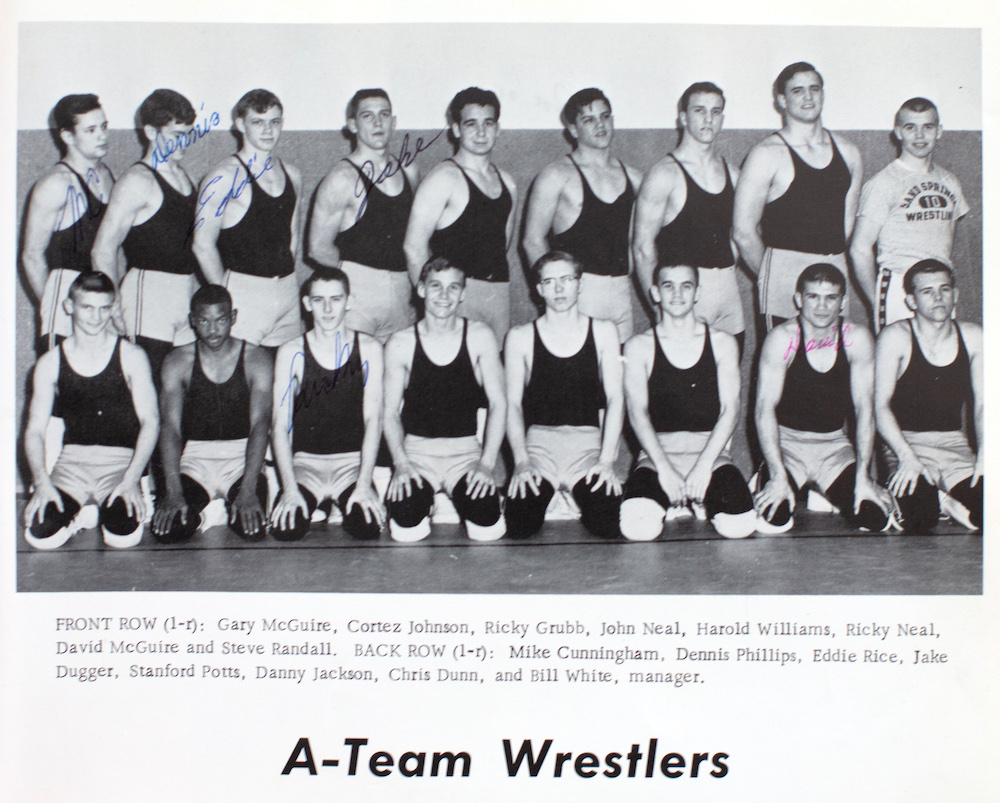

Sand Springs native John Neal investigates the integration of Charles Page High School did what no other public school had the courage to do in 1964. He looks how it impacted the Black students, their families and their community and how whites reacted to their new classmates from the former segregated Booker T. Washington High School in Sand Springs.

>> Jan. 20: The Sand Springs Keystone Corridor Redevelopment Plan reflects an abundance of ignorance or deceit.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

John Neal was a student at Charles Page High School when the first Black students were admitted. Neal says the article was the culmination of the collaborative efforts of students of both races, who wanted the story told. The white students were largely ignorant of the indignities and other obstacles the integrating students and their families experienced. The group was inspired and assisted in their efforts by James W. Russell, the CORE leader of the efforts, and contemporaneous news accounts of the events in The Oklahoma Eagle written by E.L. Goodwin Jr. The collaborative group has gained permission to post a solid bronze plaque in the high school honoring the Black students’ “courage and that of their families.” Neal is a former city manager and municipal consultant, now retired and living in Austin Texas.