By John Neal, For The Oklahoma Eagle

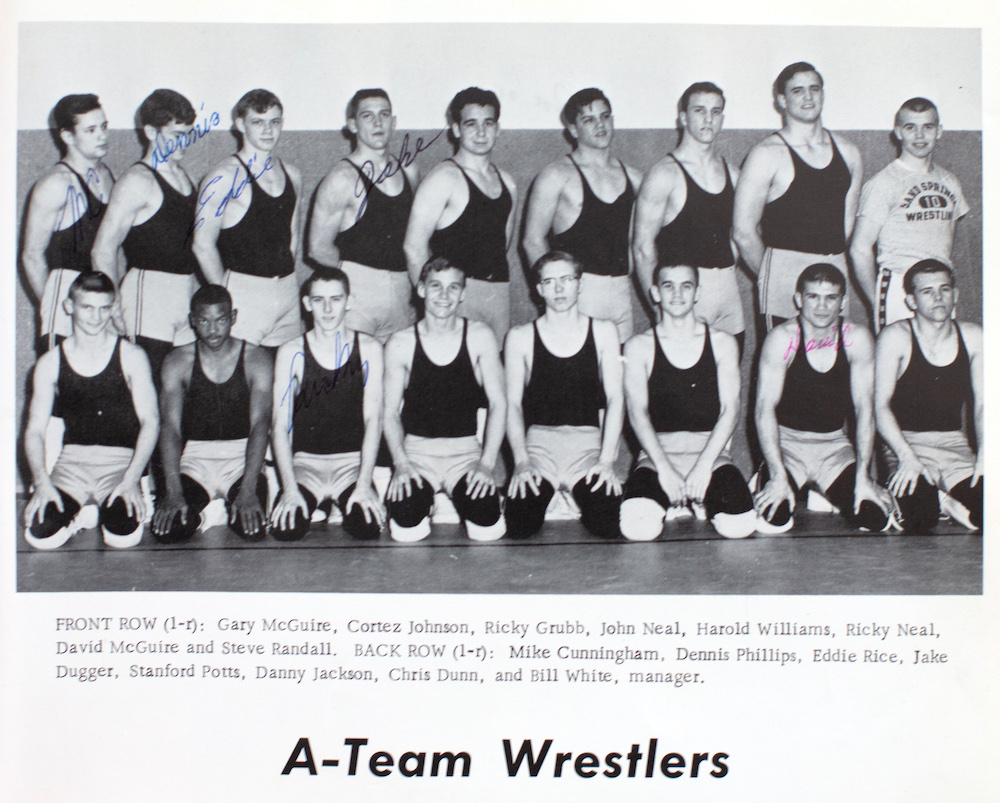

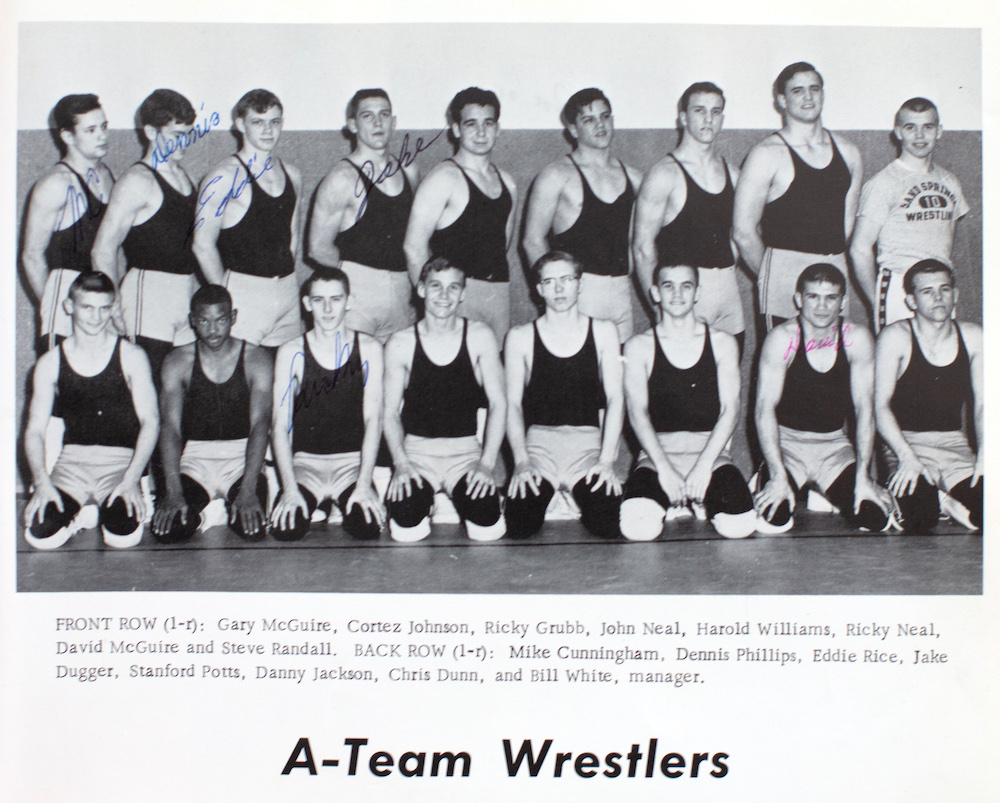

SAND SPRINGS – When classes opened at Charles Page High School in Sand Springs in the fall of 1964, most of the school was in for a surprise. Nine Blacks had joined the 900 strong student body. Until then, the school was all white.

Although the Civil Rights movement was in full sway nationally, the move to desegregate the Tulsa suburb’s only public high school was an anomaly in the Tulsa area – and throughout Oklahoma. In a landmark case, the Supreme Court had ordered school desegregation a decade earlier. The U.S. Congress had passed the Civil Rights Act that year. But school officials in nearby Tulsa — and statewide — were quietly resisting compliance with those decisions.

Tulsa public schools would remain segregated until the early 1970s, (forced to integrate after a then-young lawyer, James O. Goodwin – our publisher – initiated the first desegregation lawsuit in the City of Tulsa resulting in school desegregation.)

This is the little-known story of how proponents of integration at Charles Page pushed forward against the odds. The Sand Springs School Board and Superintendent battled to preserve segregation in public schools.

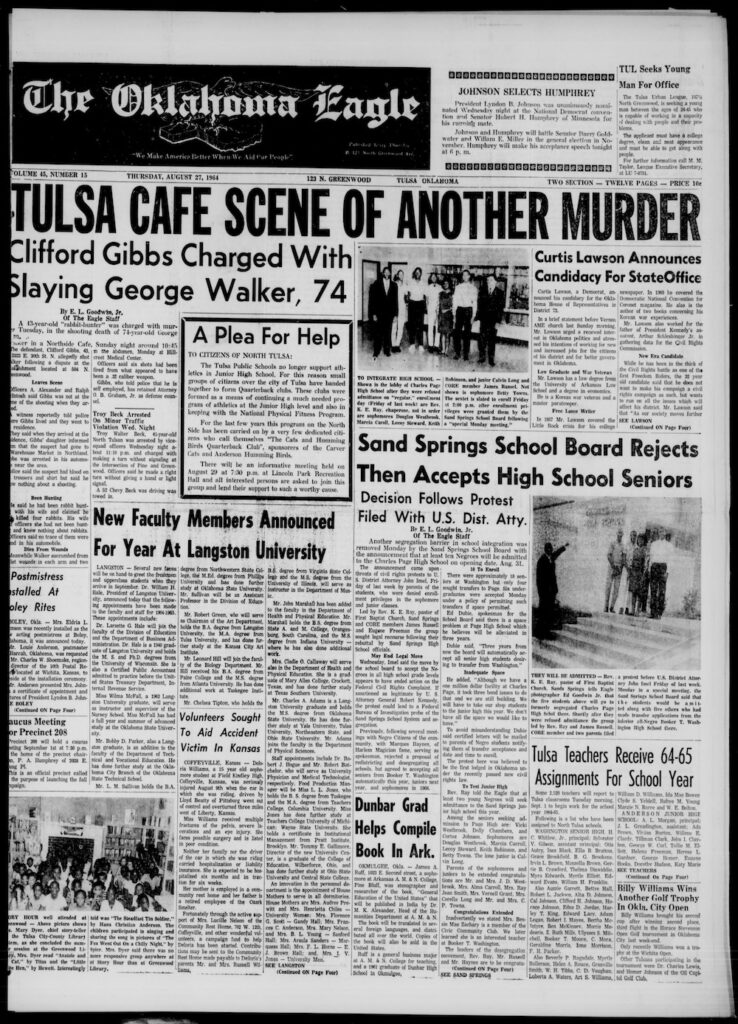

Many white residents of Sands Spring also opposed having Black kids at their school. Although support for integration among Sand Springs’s Blacks was not universal, many joined in the push to end decades of segregation in the school system. The Tulsa Chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality organized the school desegregation effort. They were bolstered by support and inspiration from professional basketball legend Marques Haynes, an African American raised in Sand Springs. In an era when school desegregation struggles were at the top of national news, the desegregation efforts in Sand Springs also received attention from afar. Only weeks after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the first complaint in Oklahoma was prepared for federal court. In its August 21, 1964 edition, the New York Times reported the saga. “Five Negro students were refused enrollment today in the 10th and 11th grades of Charles Page High School and met with United States Attorney John Imel to discuss the filing of a complaint under the Civil Rights Act of 1964,” the paper wrote.

Charles Page, town founder

The high school is named after Sand Springs founder Charles Page, still revered in that small city located just west of Tulsa. He is foremost recognized for his philanthropy. He established Sand Springs Home, a large orphanage, and Widow’s Colony, a residential housing complex for widows and children. Already wealthy when he was lured to the area by the Tulsa oil boom of the early 2Oth century, Page embarked on making an idealized city for industry and commerce.

Jamey Landis, a Sand Springs historical chronicler, summed up the business executive’s impact well. Page, he said, “swiftly set about creating his ideal industrial city with a boldness that shocked even Tulsa’s more daring business leaders. He established a transportation system, water supply, and electrical power that enabled him to hire businesses and industries with the promise of free land, low-priced utilities, and a $20,000 resettlement bonus. Sand Springs boomed and continued to thrive despite obstacles such as the great depression and violent labor disputes.”

But Page’s founding of Sand Springs was not without controversy. Among other issues, the town was segregated from its outset.

Indian land and a segregated community

Before the Dawes Act of 1887, Native American lands were held by tribes as communal property. This Act coerced tribes into severing the land into allotments to individual tribal members as private property. In a short period of time after that, they could sell the land to whites. Historian D.S. Otis wrote this Allotment Act (as it was also named) “… was one of the most important pieces of legislation dealing with Indian affairs in United States history”. It may have also been the most disastrous. Proponents of the legislation argued that this would transform Indian civilization, creating entrepreneurs and farmers, aligning its culture more closely with white society.

“On the other hand,” Otis wrote, “as has been shown, there is plenty of evidence to indicate that there were definite and powerful interests behind allotment which were not philanthropic at all; that homesteader, land companies, and perhaps railroads, saw allotment as a legal way of getting at wide areas of Indian lands.”

Thus, at the turn of the century and continuing after that, individual Indians found themselves possessing sizeable tracts of land they could sell to anyone. But they had no experience valuing the worth of the ground in a capitalistic exchange. The Five Civilized Tribes had been forcibly removed to Oklahoma via the Trail of Tears between 1830 and 1850. Following the Civil War, three dozen other tribes were also removed to Oklahoma, including the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache. These tribes lost vast acres of communal tribal land by the Allotment Act. For example, the Creeks lost two million acres of the allotted domain.

Jamey Landis noted that, “in 1908, full-blooded Creeks were allowed to sell their land to non-Native Americans.” Charles Page was one of those who quickly purchased large tracts of land. Several lawsuits resulted from these cheap land acquisitions. But Page was able to hold on to his purchases. The original Sand Springs township was platted in 1911, consisting initially of 160 acres.

That same year Page platted the Southside Addition, containing about 33 acres, for African Americans. The move established Sand Springs as a segregated community.

Another Black community was based south of Sand Springs. This area, in existence since at least 1906, later became known as Buford Colony, named after J.E. Buford, a Black educator and principal of Booker T. Washington School in Sand Springs. While Buford Colony was primarily a sprawling farming and residential area, the Southside Addition had hotels, cafes, and a grocery store in the early part of the century. The Black ancestry of the people in the two neighborhoods has not been comprehensively traced. What is known is that many Indian tribes, including those relocated to Oklahoma, owned slaves. By 1861, eight to ten thousand Black people were enslaved throughout Indian Territory. Following the Civil War, the federal government in 1866 required their emancipation. It seems likely is that Creek and other Indian tribes’ former slaves, who became known as Freedmen, may have settled in the Sand Springs area. For example, in Oklahoma, the Oklahoma Historical Society notes, that “from 1865 to 1920, African Americans created more than fifty identifiable towns and settlements, some of the short duration and some still existing at the beginning of the twenty-first century.”

Other Civil Rights protests

Oklahoma has a long history of Black civil rights struggles. The Oklahoma Constitution of 1907 did not mandate complete segregation because of fear President Theodore Roosevelt would disapprove of it with his signature. But Article XIII Section 3 stipulated the segregation of schools. The clause was finally removed by a statewide referendum in 1965.

By the middle 1900s, Oklahoma had become a hotbed of civil rights activities. Most early protests centered around restaurants and public accommodations. For example, Clara Luper led a 1958 sit-in at the Katz restaurant in Oklahoma City two years before the heralded Greensboro, North Carolina, sit-in. This sit-in led to numerous other demonstrations at lunch counters, cafeterias, churches, and amusement parks, as well as marches, voter registration drives, and boycotts. Many were successful. In the same year of the integration of CPHS, there were picket lines in front of Tulsa City Hall demanding integration; and police arrested 54 persons attempting to integrate a Tulsa restaurant.

The long shadow of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre hung over the area. The Sand Springs Leader reported that some of the refugees who escaped the massacre were sent to Sand Springs. They were provided food, shelter, and a safe environment in the “colored school building.” Some may have remained in Sand Springs. Newspaper accounts of the period portrayed Sand Springs’ role in a positive light. But it did not lead to desegregation within the community.

In 1954 Brown v Board of Education shattered the myth that school systems, one for Blacks and one for whites, could ever be equal, ruling that separate was inherently unequal. In Oklahoma, not only did the Constitution mandate segregated schools but funding for white and Black schools was separated. It was not until 1955 that resources were placed in a common school fund, but gross inequality continued.

It is against this background that the two Black communities in Sand Springs helped mobilize the fight for desegregation of the Sand Springs schools in the 1960s.

Eventually, in late summer 1964 nine Black students would enroll in CPHS for the first time. They were: Dollie Chambers, Calvin Long, Betty Towns, Cortez Johnson, Keith Robinson, Douglas Westbrooke, Marcia Jones, Marvin Stewart and Vicki Westbrooke. But the Sand Springs School board had put up a brutal fight against the teenagers entering the school that would last until days before the opening of the school year.

ABOUT THIS SERIES

Sand Springs native John Neal investigates the integration of Charles Page High School did what no other public school had the courage to do in 1964. He looks how it impacted the Black students, their families and their community and how whites reacted to their new classmates from the former segregated Booker T. Washington High School in Sand Springs.

>> Part 1 (Dec. 10): Charles Page High School’s bold – and treacherous – road to integrate in 1964

>> Part 2 (Dec. 17): How did the integration of Charles Page fare?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

John Neal was a student at Charles Page High School when the first Black students were admitted. Neal says the article was the culmination of the collaborative efforts of students of both races, who wanted the story told. The white students were largely ignorant of the indignities and other obstacles the integrating students and their families experienced. The group was inspired and assisted in their efforts by James W. Russell, the CORE leader of the efforts, and contemporaneous news accounts of the events in The Oklahoma Eagle written by E.L. Goodwin Jr. The collaborative group has gained permission to post a solid bronze plaque in the high school honoring the Black students’ “courage and that of their families.” Neal is a former city manager and municipal consultant, now retired and living in Austin Texas.