How a small group successfully pushed school desegregation in Sand Springs

John Neal and Gary Lee

The Oklahoma Eagle

PHOTO

Contributed

When the opening of the 1963-1964 school year approached in Sand Springs, a small group of local Black students made plans to enroll at Charles Page High School. As the first Black students at a school that had been all-white since it opened in 1959, they knew that they were on the cusp of making history and starting a culture change.

They feared opposition – and possibly violence – from white opponents to integration.

“We had heard rumors that we’d be met at the door by people with baseballs bats, and I don’t know what else,” recalled Calvin Long, an African American and Native Oklahoman, who was one of the Black students planning to join Charles Page. “So, yeah, we were scared.”

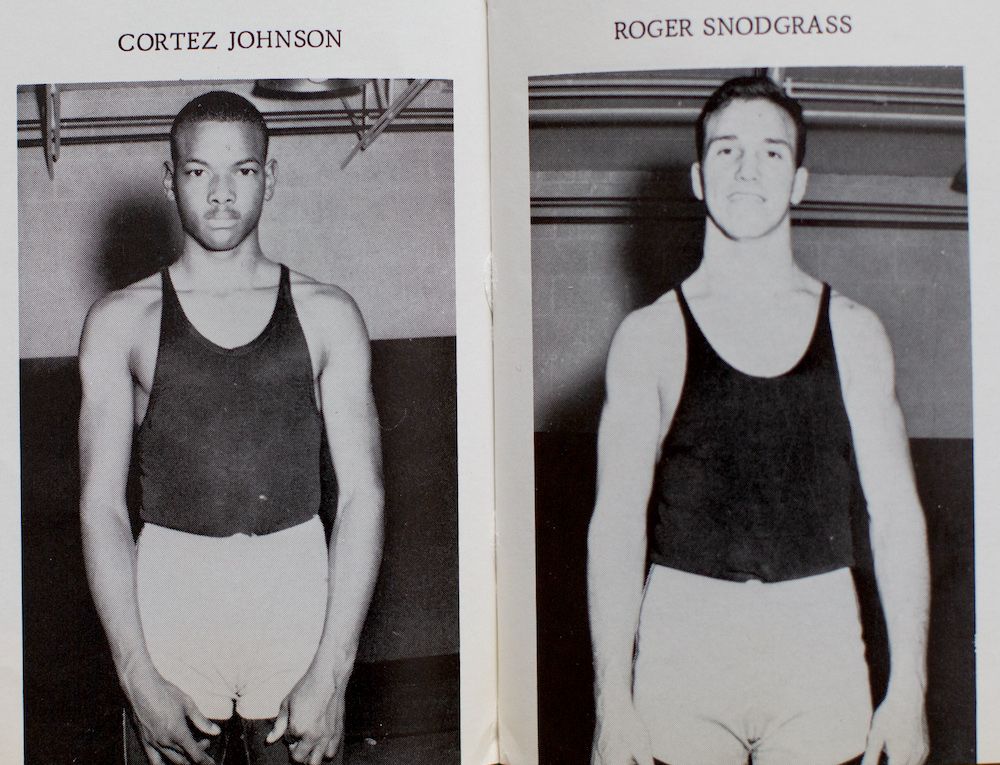

Cortez Johnson, another member of the first group of Blacks at Charles Page, concurred. “We were nervous,” he said in an interview with The Oklahoma Eagle. “Some were very nervous, others just a bit nervous.”

Other cities in the South – and elsewhere in the country – had already introduced plans to desegregate schools. But Oklahoma school boards had posed resistance – albeit often passive – to integration. Some local school districts had tried voluntary methods which the Oklahoma Board of Education had sanctioned.

But they achieved little.

For example, the Tulsa Public Schools board submitted a voluntary plan in 1965. Still, Booker T. Washington High School – located in the heart of the city’s Black community – was not fully desegregated until 1973.

In 1972, a federal court judge ordered the Oklahoma City School Board “to develop desegregation plans so the individual student populations would be reflective of the overall minority population.”

Separate and unequal schools in Sand Springs

Nonetheless, there were signs that some communities, encouraged by the 1954 landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision and vigorous civil rights actions, were slowly beginning to change in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), founded in 1942, was an inter-racial organization fighting racial discrimination. In the early 1960s, CORE had become one of the leading organizations challenging public segregation in the South. In the summer of 1964, the Tulsa chapter of CORE turned its attention to the Sand Springs school district. Their efforts were led by James W. Russell, a then-19-year-old Sand Springs resident and CORE member.

In that era, Sand Springs had become a manufacturing and industrial apex. But it remained a strictly segregated community. It was separated only by the Katy Railroad tracks. Forays by Blacks across the channels were limited to domestic help and work in a few white-owned businesses.

The stark contrast in public schools drew CORE’s attention. The Black and white schools in the small city were separate but equal.

Segregated schooling for Blacks began in a church in 1912 until the Booker T. Washington School was built for the 1914-1915 school term. Wealthy businessman and philanthropist Charles Page, who founded Sand Springs in 1911, donated the land for both the church and school. The Rosenwald Fund likely funded the school construction. Julian Rosenwald was the founder and CEO of Sears, Roebuck and Company. He partnered with Booker T. Washington to build over 5,300 schools for Blacks throughout the South from the early 1910s to the 1930s. In Oklahoma alone, 176 schoolhouses were built.

Russell, the young CORE activist, provided a snapshot to the Tulsa chapter of the organization of what all-Black Booker T. Washington School and all-white Charles Page High School were like at the time. His report documented the contrasts between the segregated schools.

Russell reported that Booker T. Washington School, located in the Southside Addition, had several hundred students aged 6 to 18, all housed in a single building. Their course curriculum offered only 35½ credits compared to Charles Page High School’s 84 credits. Many other areas – ranging from higher mathematics and Latin to auto mechanics – showed how Washington students were given inferior resources. The Booker T. school structure was decrepit. Charles Page had facilities for debate, choir, home economics, modern stagecraft, an indoor swimming pool, gymnasium, football stadium and more.

The Sand Springs Public School board and superintendent vigorously opposed integration. One justification the board initially used to deny admission to Blacks was a false claim that Charles Page wasn’t large enough to add all the Black students. This lie was later abandoned when the organizing group learned the facility was built to accommodate 1,000 students but only had 900 students. The high school division of Booker T. Washington had only 67 students.

Resistance, betrayal, success

In a preliminary meeting with CORE representatives, the Sand Springs Public School superintendent and the board clerk argued that the Booker T. Washington School was adequate, and the citizens were satisfied. Later in the meeting, they reiterated the false position that Charles Page had reached its enrollment limit and could not house all the Black high school students. However, by the end of the meeting, some school officials conceded that a partial integration was feasible.

At the next board meeting, CORE members and Black residents from the Black neighborhood attended in hopes of pursuing the discussion further. But the board refused to discuss the issue. Russell reported that the board clerk had said, “I will not be pressured by a sit-in or whatever this is.”

In response, Blacks called neighborhood meeting to develop a concrete proposal. The majority who attended favored integration. But some residents voiced reluctance and fears.

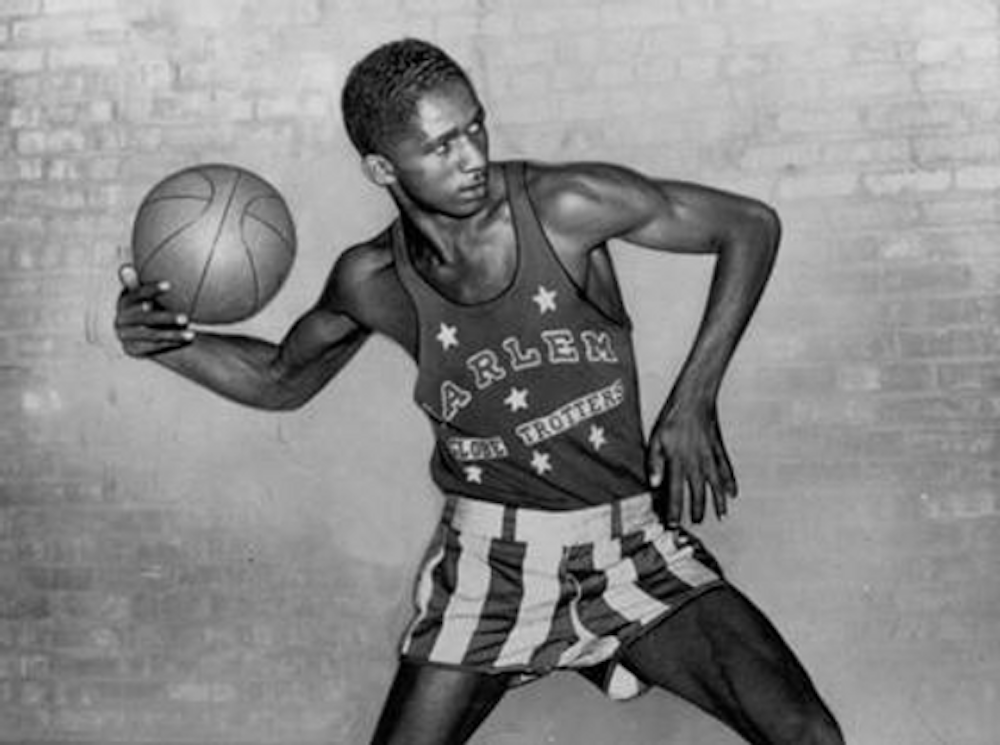

The tipping point came when Marques Haynes rose to speak. Haynes was one of the most accomplished and recognized professional basketball players of the era, starring with the Harlem Globetrotters and the Harlem Magicians. He resided near Buford Colony in Sand Springs.

“When I went to high school, I really wanted to be a printer,” he said. “But I couldn’t, because there was no printing program in this school while there was one in the white school. If we want our children to have the most opportunities in life, they have to be able to go to decent schools.”

Haynes’s position swayed the crowd.

When the board held its next meeting, Haynes presented the proposal with the support of Black community leader the Rev. Kenneth Ray. It consisted of three parts: rezoning the schools for uniformity; integrating 10th, 11t, and 12th-grade students into Charles Page; and maintaining and integrating Booker T. Washington teachers into the Sand Springs’ school system. The board rejected the proposal. But it agreed to admit 18 of the 67 eligible students.

Subsequently, using veiled threats, the superintendent attempted to deter students from applying for transfers. He told the Black students and their parents that there would be violence if they enrolled. He also voiced his view that the Black students were not smart enough to “make it.” In the end, the board refused to admit five underclassmen.

In response, the Black students and parents filed a federal court complaint to force the school to enroll the Blacks. The board relented and announced it would admit at least 10 Black students.

Fear, silence, incidents

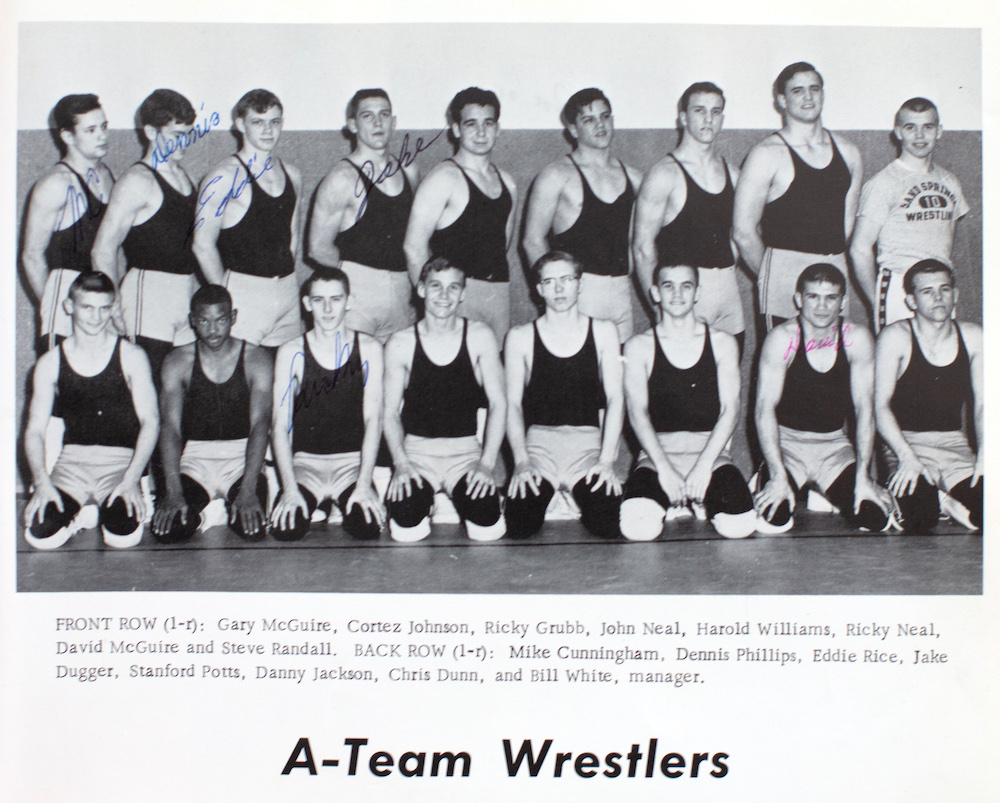

Nine Black students desegregated Charles Page in 1964.

They were seniors Dollie Chambers, Cortez Johnson and Vicki Westbrook; junior, Calvin Long; and sophomores Marcia Carroll, Keith Robinson, Marvin Stewart, Betty Towns and Douglas Westbrook.

The nine did not know what to expect.

They had all witnessed the reluctance and fear within the Black community. They had experienced resistance from the white school board and school superintendent, as well as fearful admonishments from school administrators. Yet, they had all volunteered, seeking a better education and greater opportunity.

While the students had a particular awareness of confrontation and violence at the desegregation of schools elsewhere, they surely didn’t know that violent opposition and resistance to segregation were common throughout the country.

Three years later, in 1967, more than 13 years after the Brown decision, a report by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights observed that “violence against Negroes continues to be a deterrent to school desegregation.”

In the end, the nine Black students found that the transition went surprisingly smoothly.

“None of the things we feared occurred,” Long said in an interview with the Oklahoma Eagle this week.

He acknowledged that the experience of being one of a handful of Blacks in the school was “a culture shock.” Long recalled “hearing the white kids talk about their parents buying new cars for them for their birthdays and stuff like that. That was an alien world for us.”

A skilled athlete, Long became a member of Charles Page’s basketball team in that first year and team captain in his senior year. “My reputation as an athlete made it easier for me at the school,” he said. “Everyone knew me. Sports success earned me respect. I had close friendships with the Black and white students.”

After a long reflection on his years at Charles Page, Long summed up the experience. “I knew my place,” he said. “I stood my ground. I had no problems.”

After graduation, Long attended college in Oklahoma. He became a teacher in Tulsa Public Schools and later had a career in corporate sales. Long is now 73, retired, and living in Ohio.

Cortez Johnson also said that his early worries about possible conflicts at the school were quickly allayed. One blow was when the basketball coach declined to consider him for the team. He joined the wrestling team instead and had relative success. “In the end,” he said, “I enjoyed my time there.”

Johnson, 73, is retired and lives in Tulsa.

The white students were uninformed and unprepared for their arrival. Contributing to the unpreparedness was the last-minute timing of the capitulation by the school board. The local newspaper, The Sand Springs Leader, reported on the Black student’s enrollment just days before classroom instruction but made no mention of the controversy. Nevertheless, no efforts were made to orientate the white students. Black residents were a total enigma to them.

As George Everett, a chronicler of Sand Springs history, would later note of that period, “Colored Town … was such a great sociological distance that it was easy to forget it was even there.”

White children in Sand Springs had been taught virtually nothing about the Civil War, slavery or Jim Crow. Perhaps, fortunately, they also knew nothing of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

When the Black students arrived, there was no school assembly, no teacher instruction, and few family discussions to prepare them based on informal surveys of former students. It’s as if all the adults held their breath and waited to see what would happen. Racism has to be taught and the mid-teen students were naive. Consequently, adverse events were limited.

There was neither violence, protest demonstrations, nor physical attempts to block integration despite early fears. But race-based incidents were emotionally wrenching experiences, and some microaggressions did occur.

Some Booker T. Washington teachers and administrators feared losing their jobs. Most did. Pressured by threats, James Russell’s mother moved out of Sand Springs. A prominent Black pastor, who supported desegregation, faced stiff opposition from some congregation members. Black students integrating Charles Page were rebuffed by some neighborhood members, caused by the fear that their departure would weaken the community. A team head coach at Charles Page refused to attend the tryout for a Black student. Black students remember white students lining the hallway staring in silence as they passed by them.

An interracial group of students was refused admission to a local pizza parlor.

In 1966, the Booker T. Washington School was closed, and school integration in Sand Springs was complete. One year later, the school board desegregated the rest of the Sand Springs public schools, with the superintendent issuing a statement that began in part, “While our schools have officially operated for several years under a policy of nondiscrimination…” The school and the Southside Addition neighborhood were later demolished for economic development.

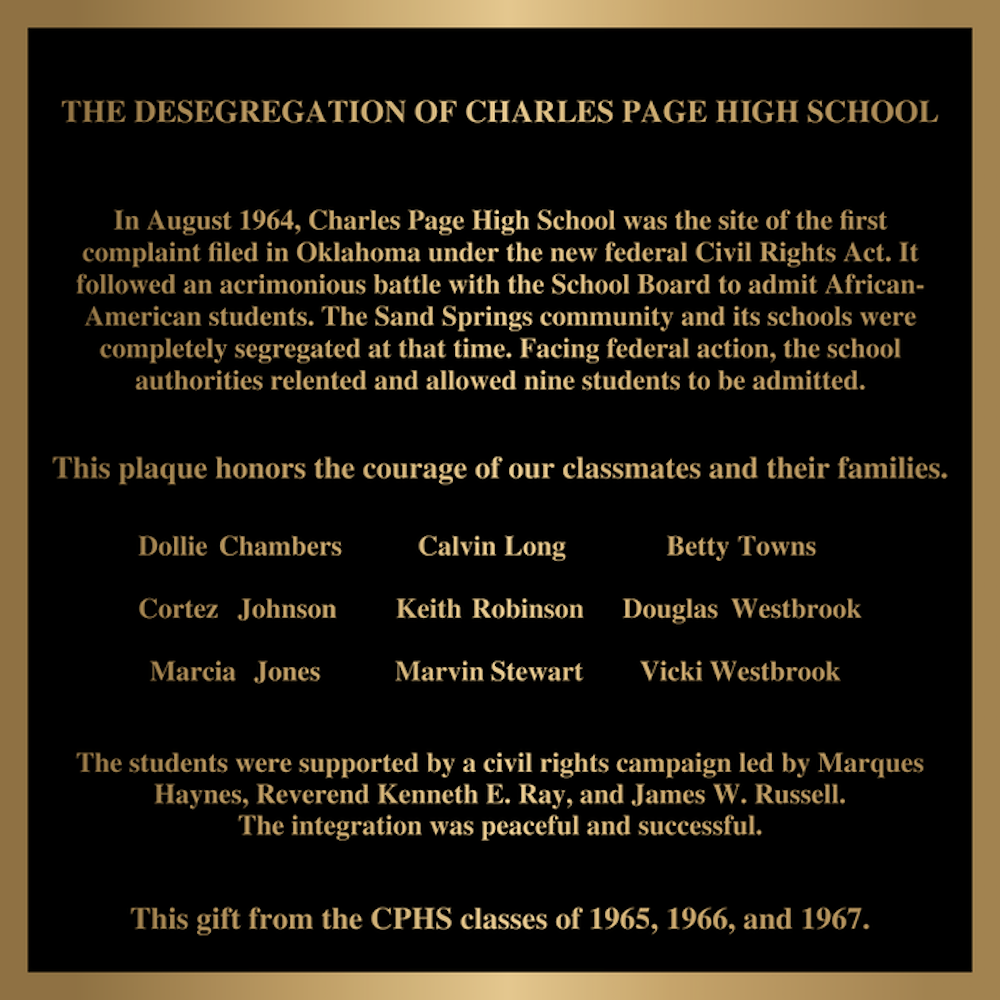

This year, a group of white and Black graduates of Charles Page from the classes of 1965, 1966,and 1967 created a plaque to honor the original nine Black students.

“The integration followed an acrimonious battle with the School Board to admit African American students,” the plaque says. “The students were supported by a civil rights campaign led by Marques Haynes, Reverend Kenneth F. Ray, and James W. Russell. The integration was peaceful and successful.”

Sand Springs’ school superintendent has pledged to have the plaque placed in the lobby of Charles Page. In early February 2022, Black and white graduates of Charles Page plan to gather for a reunion.

ABOUT THIS SERIES

Sand Springs native John Neal investigates the integration of Charles Page High School did what no other public school had the courage to do in 1964. He looks how it impacted the Black students, their families and their community and how whites reacted to their new classmates from the former segregated Booker T. Washington High School in Sand Springs.

>> Part 1 (Dec. 10): Charles Page High School’s bold – and treacherous – road to integrate in 1964

>> Part 2 (Dec. 17): How did the integration of Charles Page fare?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

John Neal was a student at Charles Page High School when the first Black students were admitted. Neal says the article was the culmination of the collaborative efforts of students of both races, who wanted the story told. The white students were largely ignorant of the indignities and other obstacles the integrating students and their families experienced. The group was inspired and assisted in their efforts by James W. Russell, the CORE leader of the efforts, and contemporaneous news accounts of the events in The Oklahoma Eagle written by E.L. Goodwin Jr. The collaborative group has gained permission to post a solid bronze plaque in the high school honoring the Black students’ “courage and that of their families.” Neal is a former city manager and municipal consultant, now retired and living in Austin Texas.