Vanessa Hall-Harper, a Tulsa city council member, and local activist Kristi Williams visit Oaklawn Cemetery, where many think there is a mass grave for people killed during the rampage. (Shane Bevel/for The Washington Post)

Vanessa Hall-Harper, a Tulsa city council member, and local activist Kristi Williams visit Oaklawn Cemetery, where many think there is a mass grave for people killed during the rampage. (Shane Bevel/for The Washington Post)

Vanessa Hall-Harper pointed to a grassy knoll in the potter’s field section of Oaklawn Cemetery. “This is where the mass graves are,” Hall-Harper declared.

She and others think bodies were dumped here after one of the worst episodes of racial violence in U.S. history: the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

For decades, few talked about what happened in this city when a white mob descended on Greenwood Avenue, a black business district so prosperous it was dubbed “the Negro Wall Street” by Booker T. Washington.

For two days beginning May 31, 1921, the mob set fire to hundreds of black-owned businesses and homes in Greenwood. More than 300 black people were killed. More than 10,000 black people were left homeless, and 40 blocks were left smoldering. Survivors recounted black bodies loaded on trains and dumped off bridges into the Arkansas River and, most frequently, tossed into mass graves.

Now, as Tulsa prepares to commemorate the massacre’s centennial in 2021, a community still haunted by its history is being transformed by a wave of new development in and around Greenwood.

There’s a minor-league baseball stadium and plans for a BMX motocross headquarters. There’s an arts district marketed to millennials, and a hip shopping complex constructed out of empty shipping containers. There’s a high-end apartment complex with a yoga studio and pub.

While almost two-thirds of the neighborhood’s residents are African American, the gentrification has surfaced tensions between the present and the past. Questions about the scope of the rampage have never been resolved. Even the description of the violence is a point of contention, with some calling it the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 and others referring to it as a massacre.

“Before my grandmother died, I asked her what happened,” said Hall-Harper, whose council district includes Greenwood. “She began to whisper. She said, ‘They was killing black people and running them out of the city.’ I didn’t even know about the massacre until I was an adult. And I was raised here. It wasn’t taught about in the schools. It was taboo to speak about it.”

Though Tulsa officials decided years ago not to excavate the site of the alleged mass grave, arguing that the evidence isn’t strong enough, Hall-Harper plans to ask the city to reconsider.

“In honor of the centennial,” she said, “I think we, as a city, should look into that and ensure those individuals are laid to rest properly.”

Acentury ago, Tulsa was racially segregated and reeling from a recent lynching when Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old shoeshiner, walked to the Drexel Building, which had the only toilet downtown available to black people. Rowland stepped into an elevator. Sarah Page, a white elevator operator, began to shriek.

“While it is still uncertain as to precisely what happened in the Drexel Building on May 30, 1921, the most common explanation is that Rowland stepped on Page’s foot as he entered the elevator, causing her to scream,” the Oklahoma Historical Society reported.

The Tulsa Tribune published a news story with the headline “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator” and ran an ominous editorial: “To Lynch Negro Tonight.”

Soon, a white mob gathered outside the Tulsa courthouse, where Rowland was taken after his arrest. They were confronted by black men, including World War I veterans, who wanted to protect Rowland.

A struggle ensued. A shot was fired. Then hundreds of white people marched on Greenwood in a murderous rage.

“They tried to kill all the black folks they could see,” a survivor, George Monroe, recalled in the 1999 documentary “The Night Tulsa Burned.”

There were reports that white men flew airplanes above Greenwood, dropping kerosene bombs. “Tulsa was likely the first city” in the United States “to be bombed from the air,” according to a 2001 report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921.

B.C. Franklin, a Greenwood lawyer and the father of famed historian John Hope Franklin, wrote a rare firsthand account of the massacre later donated to the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“The sidewalk was literally covered with burning turpentine balls,” he wrote. “For fully forty-eight hours, the fires raged and burned everything in its path and it left nothing but ashes and burned safes and trunks and the like that were stored in beautiful houses and businesses.”

On June 1, 1921, martial law was declared. Troops rounded up black men, women and children and detained them for days.

Olivia Hooker, now 103, is one of the last survivors of the massacre. Hooker was 6 when the violence erupted.

Her mother hid her and three of her siblings under their dining room table. “She said, ‘Keep quiet, and they won’t know you are under here.’ ”

From beneath the oak table, she and her siblings watched in horror.

“They took everything they thought was valuable. They smashed everything they couldn’t take,” Hooker said. “My mother had these [Enrico] Caruso records she loved. They smashed the Caruso records.”

Hooker, who later became one of the first black women to join the Coast Guard, has always lived with her memories of that racial terrorism.

“You don’t forget something like that,” said Hooker, who lives in New York. “I was a child who didn’t know about bias and prejudice. . . . It was quite a trauma to find out people hated you for your color. It took me a long time to get over my nightmares.”

It wasn’t until 1998 that authorities began investigating the claims of mass graves. Investigators used electromagnetic induction and ground-penetrating radar to search for evidence at Newblock Park, which operated as a dump in 1921, Booker T. Washington Cemetery and Oaklawn Cemetery.

At each site, they found anomalies “that merited further investigation,” according to the commission’s report.

Then in 1999, a white man named Clyde Eddy, who was 10 at the time of the massacre, came forward and told officials he was playing in Oaklawn Cemetery in 1921 when he spotted white men digging a trench. When the men left, Eddy said, he peeked inside the wooden crates and saw corpses of black people.

Based on Eddy’s story, state archaeologists began investigating the section of the cemetery Eddy cited. The effort was led by Clyde Snow, one of the world’s foremost forensic anthropologists who had helped identify Nazi war criminals and had determined that more than 200 victims found in a mass grave in Yugoslavia had been killed in an execution style of ethnic cleansing.

Using ground-penetrating radar, they made a dramatic discovery: an anomaly bearing “all the characteristics of a dug pit or trench with vertical walls and an undefined object within the approximate center of the feature,” the commission concluded. “With Mr. Eddy’s testimony, this trench-like feature takes on the properties of a mass grave.”

The commission, created by the Oklahoma legislature in 1997 to establish a historical record of the massacre, recommended “a limited physical investigation of the feature be undertaken to clarify whether it indeed represents a mass grave.”

It never happened.

Susan Savage, who was mayor of Tulsa at the time of the proposed excavation, said in a recent interview that she had numerous discussions with officials and raised concerns about the excavation.

“Oaklawn Cemetery is a public lot,” Savage recalled. “I asked, ‘How do we do that without disturbing graves of family buried there?’ I wanted to know how we [could] protect and preserve the dignity of people there.”

Bob Blackburn, who is white and served on the commission, said he agreed with the decision not to dig at Oaklawn.

“Based on all the evidence Clyde Snow looked at, we never could pinpoint something,” he said. “In my mind that is not an unresolved issue. In terms of proving there was a mass grave, there will always be people thinking one way or the other.”

The refusal to excavate was a blow, Hall-Harper said, along with the city’s decision to ignore a recommendation for reparations to survivors and descendants of survivors.

She worries that the gentrification underway does not include efforts to resolve lingering questions about the violence.

“This is sacred ground,” Hall-Harper said. “As developers are making decisions about the Greenwood district, the history is being ignored, and I think it is intentional. They want to forget about it and move on.”

J. Kavin Ross, who wrote about the mass graves for the Oklahoma Eagle Newspaper, a black-owned publication that has been headquartered in Greenwood since 1936, said gentrification has pushed many black residents and descendants of massacre survivors out of Greenwood.

“With gentrification—we say, ‘Now you want to take an interest in Greenwood and pimp our history? And you are going to build these apartments down here, and you know darn well we are not going to spend $1,000 for a closet room,” Ross said. “We will never be able to afford to live in Greenwood.”

At Greenwood and Archer, in the heart of Negro Wall Street, sit 14 red brick buildings that were reconstructed soon after the 1921 massacre. They are all that’s left of the original Greenwood.

Tulsa Drillers fans head to the ballpark downtown. The stadium sits at the edge of the Greenwood Historic District. (Shane Bevel/Shane Bevel Photography)

Tulsa Drillers fans head to the ballpark downtown. The stadium sits at the edge of the Greenwood Historic District. (Shane Bevel/Shane Bevel Photography)On a hot summer afternoon, David Francis pushes open the door at Wanda J’s Cafe, a soul-food restaurant where black and white residents mingle.

Francis, 32, lives nearby and loves Wanda J’s chicken-fried steak and green beans. A white man born and raised in Tulsa said he first heard about the massacre when he was in high school.

“It’s unbelievable to think the genuine atrocity took place right here,” said Francis, looking outside the restaurant window onto Greenwood Avenue. “A white woman told me she remembered seeing bodies dumped into the Arkansas River off a bridge.”

The African American diners at Wanda J’s fear the changes in Greenwood, including OneOK Field, the minor-league ballpark that opened in 2010, and the luxury GreenArch apartment complex, which features a yoga and indoor cycling studio. The BMX headquarters and track are set to open next year on the edge of the historic district at Archer and Lansing.

Bobby Eaton Sr., 83, orders a cup of coffee and calls the influx of white businesses and residents “a tragedy.”

Junior Williams, 56, said gentrification is driven by the same forces that fueled the white mob nearly 100 years ago. “There was economic jealously that caused them to destroy Greenwood.”

At Lefty’s on Greenwood, where the crowd is overwhelmingly white, Nicci Atchoey said she moved into the GreenArch apartments because of its history. But Atchoey, a 39-year-old white Realtor who grew up in Tulsa, learned the details of the massacre only six years ago.

“It is really not something taught in schools,” said Atchoey, adding that many white people move to Greenwood oblivious about the history.

“I think that is unacceptable. People come to the area and go to the bars and ballgame,” she said. “The stadium is like building a Whole Foods at the site of the Oklahoma City bombing.”

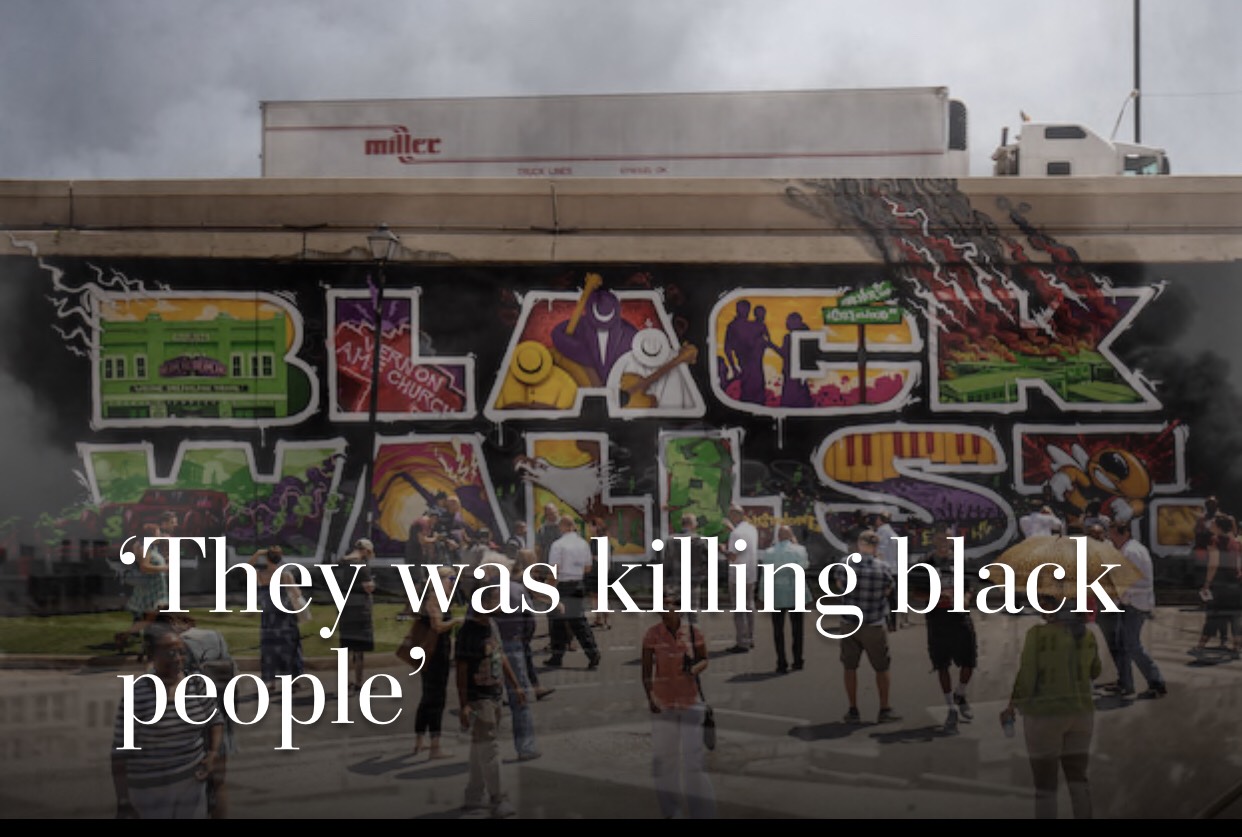

As evening falls, the crowds heading to the baseball game walk over the plaques in the sidewalk dedicated to businesses destroyed in the massacre.

Near the stadium’s entrance, under Interstate 244, a mural is signed “Tulsa Race Riot 1921.” Someone has crossed out “riot” and written “massacre.” Someone else has crossed out “massacre” and left a scribble of black spray paint.