By David Rooney

Chiwetel Ejiofor plays real-life American evangelical preacher Carlton Pearson, who alienated much of his massive flock by realigning his beliefs about a vengeful God in Joshua Marston’s Netflix feature.

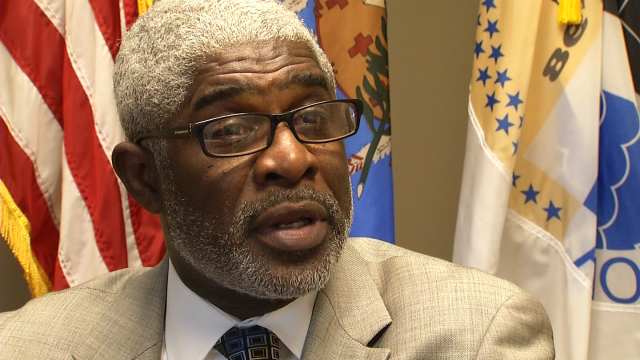

Fourteen years after wowing Sundance with his feature debut, Maria Full of Grace, director Joshua Marston returns with arguably his most powerful work since that harrowing drug and migration drama. Developed from a story broadcast on Ira Glass’ long-running public radio show This American Life about the crisis of faith that shook renowned Pentecostal bishop Carlton Pearson in the late 1990s, Come Sunday is a mesmerizing contemplation of the clash between rigid dogma and considered reinterpretation. The fact that it comes down on the side of mind-opening inclusion makes it an especially timely discussion in the current national climate.

This is a rare film about an evangelical church from outside the faith-based channels that questions without either judging or condescending. That respectful approach, along with stirring performances from a terrific cast led by Chiwetel Ejiofor should draw both religious and secular audiences to this consummately crafted Netflix original.

The movie opens on the pages of a well-thumbed Bible, covered with detailed notations, an image that indicates both the probing nature of the subject’s calling and the depth and complexity of Marcus Hinchey’s intelligent screenplay. If that suggests more of a theological debate than a dramatic narrative, don’t be misled. The story here follows the classic outline of a man of unimpeachable principles who adopts an unpopular position and stands by it against the advice of those closest to him. He loses almost everything, then comes back from despair with fortified convictions, beginning a liberating new chapter in his life.

With a rich oratorical style and a surprisingly robust vocal command when leading a congregation in rousing song, Ejiofor disappears entirely into the role of Pearson, who at the start of the film is one of the foremost leaders of the Pentecostal movement in America. He heads the massive Higher Dimensions Evangelistic Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma, which had achieved a rare feat in that part of the country by bringing black and white worshippers together.

Carlton is introduced on a business flight, during which his intuitive words draw his seatmate, a flinty lawyer (Allie McCulloch), away from her red wine and case files in a mutually confessional conversation that reduces her to tears as she admits she’s a mess. The filmmakers then slyly cut to the dynamic preacher mid-sermon, recounting that experience to his flock as an illustration of their shared commitment to “save” that woman and all sinners like her.

Marston and Hinchey swiftly establish the vast scope of Higher Dimension’s operations, with a busy travel schedule of preaching engagements beyond the home base. Carlton’s inner circle includes his fellow church founder and primary business manager Henry (Jason Segel), music director and organist Reggie (Lakeith Stanfield), and senior staffer Nicky (Stacey Sergeant).

Hovering on the edge of that circle is his younger wife and mother of his children, Gina (Condola Rashad), an independent-minded outsider seemingly chosen by the organization for the role of the dutiful spouse, which she finds as uncomfortable as the fussy church hats she’s obliged to wear.

When Carlton’s incarcerated Uncle Quincy (Danny Glover, in a single indelible scene) asks him to intercede on his behalf in a parole issue, the preacher refuses despite his love for the old man who practically raised him, recognizing Quincy’s plea for religious salvation as insincere. The tragedy that follows sufficiently shakes Carlton to send him to his college mentor and father figure Oral Roberts (Martin Sheen, superb) for advice, voicing his frustration about being unable to save many of the people he grew up with from backsliding. Roberts uses the suicide of the gay son he could never accept as an example of an enormous test that ultimately strengthened his faith.

These are meaty scenes with dark moral shadings and quietly roiling emotional undercurrents. They lay the foundations for Carlton’s divine epiphany as he watches news footage of the hundreds of thousands killed in the Rwandan genocide.

During the following Sunday’s service, he shocks his congregation by asserting that those African refugee victims will escape eternal damnation despite never having accepted Christ in the manner of the Pentecostal doctrine. Those first public words of universal reconciliation, openly questioning the existence of Hell, contradict everything the congregation has been taught. Despite the urging of Henry, Oral and others, Carlton refuses to recant the following Sunday, advocating for a more nuanced reading of the Bible and triggering a steady exodus of his angered flock.

With unstinting compassion, the film traces the dismantling of all that Carlton and his congregation have built together, never losing sight of the personal cost to him as he continues to wrestle with his beliefs. The pain of Henry’s exit, along with other church elders, is conveyed in a strong scene in which Ejiofor’s raw emotion is countered by Segel’s balance between Henry’s firm resolve and the depth of his feelings for his friend of 20 years. Recalling his work in the under-appreciated The End of the Tour, Segel again shows here how good he can be in serious roles.

Perhaps the most moving exchanges are those between Carlton and Reggie, whose love for the bishop is wrapped up in his dependence on the church to “save” him from his homosexuality. Stanfield matches Ejiofor in one complex, conflicted note after another; their final scene together is shattering.

There’s also exquisite range and modulation in the interplay between Carlton and Gina. Rashad’s impressive gifts as a stage performer until now have not been equaled on screen. But her skillfully drawn character is one of the movie’s most intriguing figures; having long bristled at being a mere appendage, Gina is open to the idea of exploring new directions long before Carlton has accepted that necessary next step.

Come Sunday premiered at Sundance with a temporary soundtrack and will be released with a score by multicultural composer Tamar-kali, who did the music for Mudbound. But already the film has a graceful, stately flow that showcases Marston’s deft touch at shaping tone and building dramatic momentum while continuing to broach provocative questions. Scenes that could have been played to the hilt, like Carlton’s audience before the Joint College of African-American Bishops — effectively a trial for heresy — or his revelatory guest sermon at a progressive church that welcomes all outcasts, instead unfold with relatively sober economy, making the uplifting conclusion all the more affecting.

The movie’s pounding heart is the remarkable Ejiofor. Imbuing his role with authority, charisma, mighty strength and wrenching human frailty, he’s enough to make believers of all of us.

Cast: Chiwetel Ejiofor, Condola Rashad, Jason Segel, Martin Sheen, Lakeith Stanfield, Danny Glover, Stacey Sergeant, Ric Reitz, Tonea Stewart

Distribution: Netflix

Production company: Endgame Entertainment, This American Life

Director: Joshua Marston

Screenwriter: Marcus Hinchey, inspired by a story broadcast on This American Life

Producers: Alissa Shipp, Julie Goldstein, Ira Glass, James D. Stern

Executive producers: Jonathan Montepare, Lucas Smith, Cindy Wilkinson Kirven, Marc Forster, Brad Simpson

Director of photography: Peter Flinckenberg

Production designer: Richard Sherman

Costume designer: Ann Walters

Editor: Malcolm Jamieson

Casting: Billy Hopkins, Ashley Ingram

Venue: Sundance Film Festival (Premieres)