LOCAL

Kimberly Marsh, The Oklahoma Eagle

Image, Adobe Images

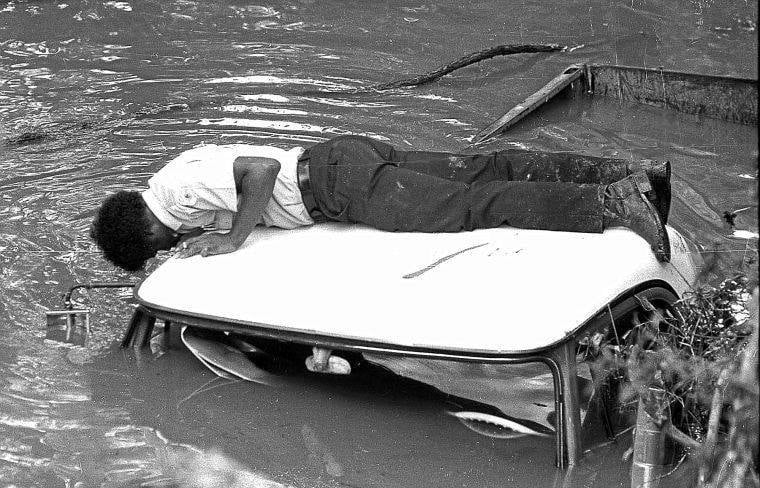

Following deadly floods in the 1980s, Tulsa reinvented its mitigation efforts

Joe Kralicek’s job is to warn and protect Tulsans during times of natural disaster. These days, his agency is on high alert.

An abnormal summer of heavy rains coupled with the persistent threat of federal cuts to weather warning systems has Kralicek facing an existential crisis.

He’s the director of the Tulsa Area Emergency Management Agency.

“I make data-driven decisions. And for that, I need the National Weather Service properly staffed and resourced,” Kralicek said.

He added that federal grants the city relies on, like FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities, are now in jeopardy.

With the deadly July floods in Kerr County, Texas and New Jersey, the issue is top of mind for Kralicek.

It begs the question, what would happen today if 18 inches of rain – equal to about four months –pounded Tulsa in just four hours? Without the early investments the city made to its stormwater system, it would have been devastating.

“Tulsa pursued mitigation. We did floodplain buyouts. We engineered our way out of being a flood-prone city,” Kralicek said.

Tulsa’s history with flooding

The 1970 Mother’s Day Flood of Mingo Creek drove families to rooftops.

The 1984 Memorial Day weekend event occurred after a rainstorm stalled over the city, dumping 15 inches in six hours. Fourteen people were killed, 288 injured and the city suffered $180 million in damages.

Then in 1986, the Arkansas River flowed over its banks, forcing the Corps of Engineers to release more than 300,000 cubic feet per second from Keystone Lake. That’s more than four times the average flow of Niagara Falls.

How the city responded

Homeowners told city leaders they’d had enough. They began a grassroots effort to strategically shape policies, funding, land use, and infrastructure to lead the nation in stormwater resiliency by the early 1990s.

Dubbed Tulsa’s great drainage war, the public/private movement led to stronger land-use controls, relocated more than 900 structures out of the floodplain, and implemented hazard mitigation plans.

“We used to have a catastrophic flood every two years. Today, we’re the most flood resistant city in the United States,” Kralicek said.

Although it was controversial, public officials joined with citizen advocates in 1986 to implement a stormwater utility fee to fund proactive disaster planning.

“The real story? Mitigation works — if you have the political will,”

The fee supports property buyouts, clearing debris from channels and storm drains and maintaining detention ponds that replace flooded properties. Residences pay an average of $12.22 monthly.

“A lot of our beautiful parks are also stormwater detention areas. They were created from floodplain buyouts. They flood, but there are no homes, no people. And that’s by design.”

The stormwater fee will continue to work for Tulsa – for now. If federal funds dry up, Kralicek says it won’t be enough to support crucial projects, like fixing streets where traffic gets shut down during hard rains.