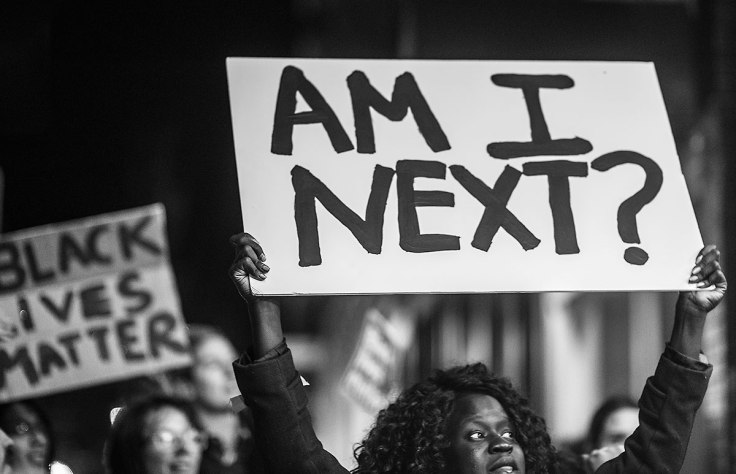

You know about the dangers of smoking, obesity, fatty foods, unprotected sex, and environmental pollutants. Now chalk up another health hazard to that ever-growing list: Racism.

It plays a key role in the development of illness — and countering it should be considered a public health issue, says a psychiatrist in the latest issue of the British Medical Journal. “Considering racism as a cause of ill health is an important step in developing the research agenda and response from health services,” writes Kwame McKenzie, MD, a psychiatrist at Royal Free and University College Medical School in London.

Despite general agreement that racism is wrong, he says there is little evidence of concerted initiatives to decrease its prevalence.

The health effects of racism are well documented. One British study of 4,800 people finds that those who felt victimized by discrimination and forms of racism were twice as likely to develop psychotic episodes in the next three years. Meanwhile, a group of Harvard researchers documented that a mere 1% increase in incidences of racial disrespect translates to an increase in 350 deaths per 100,000 African Americans.

How? Being on the receiving end of overt or subtle racism creates intense and constant stress, say some experts, which boosts the risk of depression, anxiety and anger — factors that can lead to or aggravate heart disease. Some research also suggests racism can also manifest itself in respiratory and other physical problems.

“We know that black folks are at higher risk of hypertension, but in childhood, there are no differences between black and white blood pressure rates,” says Camara P. Jones, MD, MPH, PhD, research director of Social Determinants of Health for the CDC and a leading specialist on the health impact of racism. “By the time you get into the 25-44 year-old group, you start to see changes. We have evidence that in white folks, blood pressure is dropping at night, but not in black people.”

Her theory on one reason: “There’s a kind of stress, like you’re gunning your cardiovascular engine constantly if you’re black that results from dealing with people who are underestimating you, limiting your options,” she says. “It results from little things like going to a store and if there are two people at the counter — one black and one white — the white person will be first approached. If you have stress from other sources, like a bad marriage, it’s not something you think about constantly. But the stresses associated with racism are chronic and unrelenting.”

In surveys she conducted, she finds that whites rarely think about their race in the course of a day. “But 22% of blacks surveyed said they constantly think about their race, and 50% said they think of race at least once a day — they are constantly reminded of their blackness,” she says. “That has a profound effect on health.”

In addition to stress, numerous studies show that racial and ethnic minorities tend to receive lower-quality healthcare than whites — even when insurance status, income, age, and severity of conditions are comparable, according to a recent report by the National Academies’ Institute of Medicine (IOM). And in reviewing 81 studies comparing cardiac care received by black and white patients, the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation and the American College of Cardiology Foundation report that 68 — a full 84% — indicated that race played a role in the type of care received, with blacks getting inferior treatment.

“We all know that African Americans, Hispanics, and other ethic minority groups live sicker and die younger — but this occurs even when we control for social class and income,” says H. Jack Geiger, MD, ScD, of the City University of New York Medical School, who helped research the IOM report and other studies examining how racism impacts health outcomes. “People of color have a variety of disadvantages, including lack of access to care, lower income, less insurance. But if you take two people with the condition who have the same income and insurance, the minority is less likely to get the same treatment.”

Who’s to blame? Doctors get their share, says Geiger. “It’s not that they practice overt racism; it usually happens without awareness,” he says. “And that’s one reason why most physicians are very reluctant to recognize this in themselves or their peers.” There also other factors that influence medical care, such as a greater mistrust of the medical community among minorities, as well as communication problems between physicians and their cultural different patients.

The solution? “Health services and individuals should monitor prescriptions and medical interventions to see whether or not there are differential patterns by race,” suggests Jones. “Physicians should actively guard against making assumptions about their patients, and connect with each patient by identifying something that they have in common with that patient. And researchers need to shift their focus from individual-level risk factors, like physical inactivity, to societal-level risk factors like neighborhood safety and resource constraints that lead to physical inactivity.”

Sources:

- British Medical Journal, Jan. 11, 2003

- Camara P. Jones, MD, MPH, PhD, research director Social Determinants of Health, CDC

- H. Jack Geiger, MD, ScD, department of Community Health and Social Medicine, City University of New York Medical School, The Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education, New York

- National Academies’ Institute of Medicine report, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, March 20, 2002

- Why the Difference?, a report by the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation and the American College of Cardiology Foundation, October 2002.

next: The Biochemistry of Panic

~ anxiety-panic library articles

~ all anxiety disorders articles