|

Enjoy this article using our audio content player

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

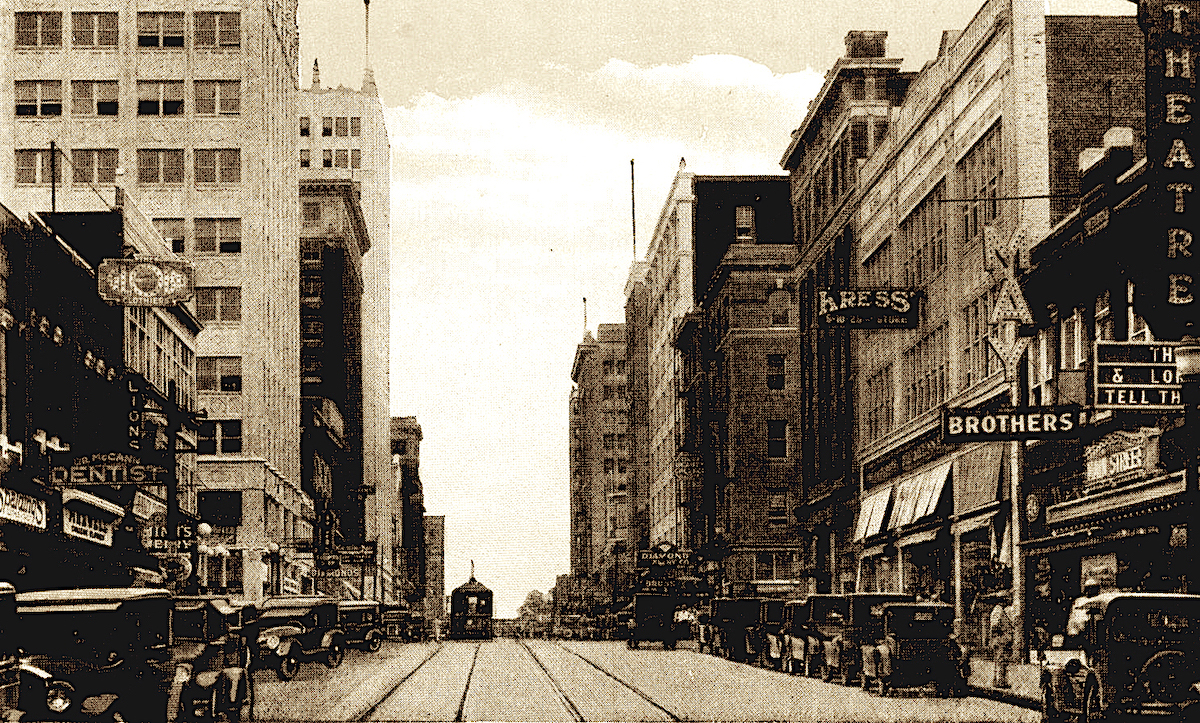

In November 1916, a week after the re-election of President Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic Party held an orgiastic parade in downtown Tulsa. Brass bands blared, revelers waved Roman candles, and donkeys strung up with decorative lights sauntered past Convention Hall. Tate Brady, a prominent real estate developer whose name already adorned city streets, led the parade on a large white Missouri mule. Behind him, marchers waved the flag of the Confederate Army–or as Brady referred to it, the “Lost Cause.”

Onlookers complained in the Tulsa World that waving the Confederate flag through city streets and draping it over automobiles was unpatriotic. Brady and another Tulsa realtor named Merrit J. Glass penned an aggrieved response in the Tulsa Democrat. The two men, both members of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, defended the flag, the Confederacy, and the ongoing project of maintaining white supremacy by any and all means. “They breathe the same spirit of the carpet-bagger government of the south,” the men said of the World, “which openly boasted of its intention and purpose to put the white man’s neck under the black man’s heel, and would have succeeded had not an all-wise Providence sent the Army of the Invisible Empire (the Ku-Klux Klan) to the rescue of the stricken Southland.”

Brady and Glass embraced the Klan’s past role as an insurgent “army.” They went further, voicing their contempt for the progress black people had achieved more recently in their home state. “It is the same kind of newspaper that under Republican rule in the early days of Oklahoma, elected negroes to office, advocated and enforced negro equality in the schools and railways, and elected a negro, McCabe for state auditor,” they wrote. “Thank God! This element does not control the republican party and these who now criticize only exhibit their denseness.”

Brady and Glass drew inspiration from the Klan’s bloody history; they stated plainly that they not only opposed black equality but endorsed the use of violent means to stop it. They became Klan members themselves when the group re-emerged in Oklahoma around the time of the massacre.

So it was more than a little strange when, only 24 hours after a white mob had finished setting fires in Greenwood, Merrit J. Glass presented a plan to Tulsa’s white leaders to remove black people from the neighborhood permanently. Not out of racist malice, but for the purpose of “developing a greater Tulsa.”

—-

The story of white Tulsa’s institutional response to the massacre is both complicated and purposefully obfuscated. Meeting minutes and official correspondence are hard to come by, despite the fact that a power struggle over Greenwood’s future played out quite publicly in the pages of the World and the Tribune (the Democrat changed its name to the Tribune in 1920). For all the money and effort the city of Tulsa is spending to uncover mass graves, there has been no parallel public initiative to seek documents that might implicate government officials who sought to profit off Greenwood’s destruction and may have helped coordinate that destruction before it happened. A lawsuit filed by massacre survivors and descendants against the city of Tulsa, the Chamber of Commerce, and other local institutions may uncover such documents, if they exist, in due time.

I have no evidence of a coordinated plan to destroy Greenwood and don’t spend my time looking for one. I’m not a detective or a particular fan of “true-crime” journalism. What I’m interested in is how powerful people and institutions often mask their true motives while operating in plain sight. The lie said straight to your face is often the most pernicious one, and the one that a knowledge of history helps to guard against. That’s the information that’s most valuable in a modern context. And so the story of Merrit J. Glass, who transformed from a blatant white supremacist to a humble negotiator seeking to foster a “co-operative spirit,” is especially instructive.

In 1921, Glass was the president of the Tulsa Real Estate Exchange, a group of city boosters who saw both profit and righteousness in ceaseless territorial expansion. His vice president, Clark Whiteside, also had KKK ties; according to a 1928 registry, Whiteside’s father was a Klan member. Six months after the massacre, Clark Whiteside implied that lynchings were an appropriate response when citizens believed the criminal justice system was not punitive enough, telling the Tulsa World, “When [people] have stood all that human nature can possibly bear, there are likely to be some ‘necktie parties,’ if one is to judge by what has happened in the past.”

On June 2, the day after the massacre, the Tulsa Real Estate Exchange was able to lay out with startling efficiency a comprehensive plan for taking over Greenwood. The exchange would appraise the value of all land in the burned-out district, owned by both blacks and whites. Then, based on those property values, the Exchange would buy out all the landowners and build an industrial site in Greenwood, likely to be used to expand railroad capacity. Black Tulsans would receive aid in building a new neighborhood northeast of Greenwood, equipped with sewage and electric lines. But they would be explicitly banned from building wooden shacks in Greenwood as they struggled to reassemble their lives.

The Real Estate Exchange set up a tent in the days after the massacre at the corner of Greenwood Avenue and Brady Street, where landowners and renters could come to report their losses. On the filing form, the organization warned residents “not to consult attorneys or make claims for insurance independent of the exchange” (many blacks ignored this advice; Loula Williams was already seeking legal aid from her personal lawyer on June 2). The Exchange expected to value black-owned property at about $500 per lot. As an industrial area, it would be worth $1,750 per lot. Before the massacre, many lots in the area had already fetched values well above $500, according to property records.

Relocating the black neighborhood would also reduce mixing between the races and black access to jobs and opportunities in downtown Tulsa. This was not an ulterior motive. It was plainly stated in the Exchange’s initial proposal: “We further believe that the two races being divided by an industrial section will draw more distinctive lines and thereby eliminate the intermingling of the lower elements of the two races, which in our opinion is the root of evil which should not exist.”

Exactly how Greenwood residents felt about this proposition is hard to ascertain. Glass, of course, did his best to speak for them, claiming that R.T. Bridgewater, a prominent black doctor, had “taken the lead in urging co-operation for a greater Tulsa among Greenwood property owners.” But when Bridgewater actually attended a meeting with the Real Estate Exchange, he demanded answers about whether blacks would be able to collect their insurance claims or receive favorable long-term loans to rebuild in a new area. The Tribune reported that prominent Greenwood leaders such as Barney Cleaver and O.W. Gurley were willing to sell, but the men were not quoted directly, and the newspaper had already publicly declared its agenda to see that “Niggertown” never be rebuilt. It was hardly an objective source.

Almost every local claim about what black people were thinking was passed through a white filter. The one exception is a surviving editorial from the Oklahoma Sun, the Greenwood newspaper that succeeded the Tulsa Star after A.J. Smitherman was banished from Tulsa during the massacre. “In the midst of our dilemma, loan sharks and conniving persons will suggest you sell out and leave,” the Sun reported. “They will tell you that fate is against you if you remain in Tulsa. Such persons should be spurned for they are not your friends. They will profit through your temporary misfortune and embarrassment.”

Glass’s plan to buy out black Tulsa ultimately fell apart (Brady also served on one the city’s reconstruction committees, but he was not as publicly vocal in his efforts to seize Greenwood). The city commission tried to codify Glass’s recommendation that blacks not be allowed to build wooden shacks by passing a fire ordinance that limited low-cost construction in Greenwood. But neighborhood lawyers such as B.C. Franklin challenged the new law, and a judge deemed it unconstitutional. By the end of summer, black-owned buildings were rising in Greenwood once again; the conspiracy that had been sold as a favor to black people had failed. But the quest for actual restitution for massacre victims was only just beginning.