Leesa Davis

New York Amsterdam News

ILLUSTRATION

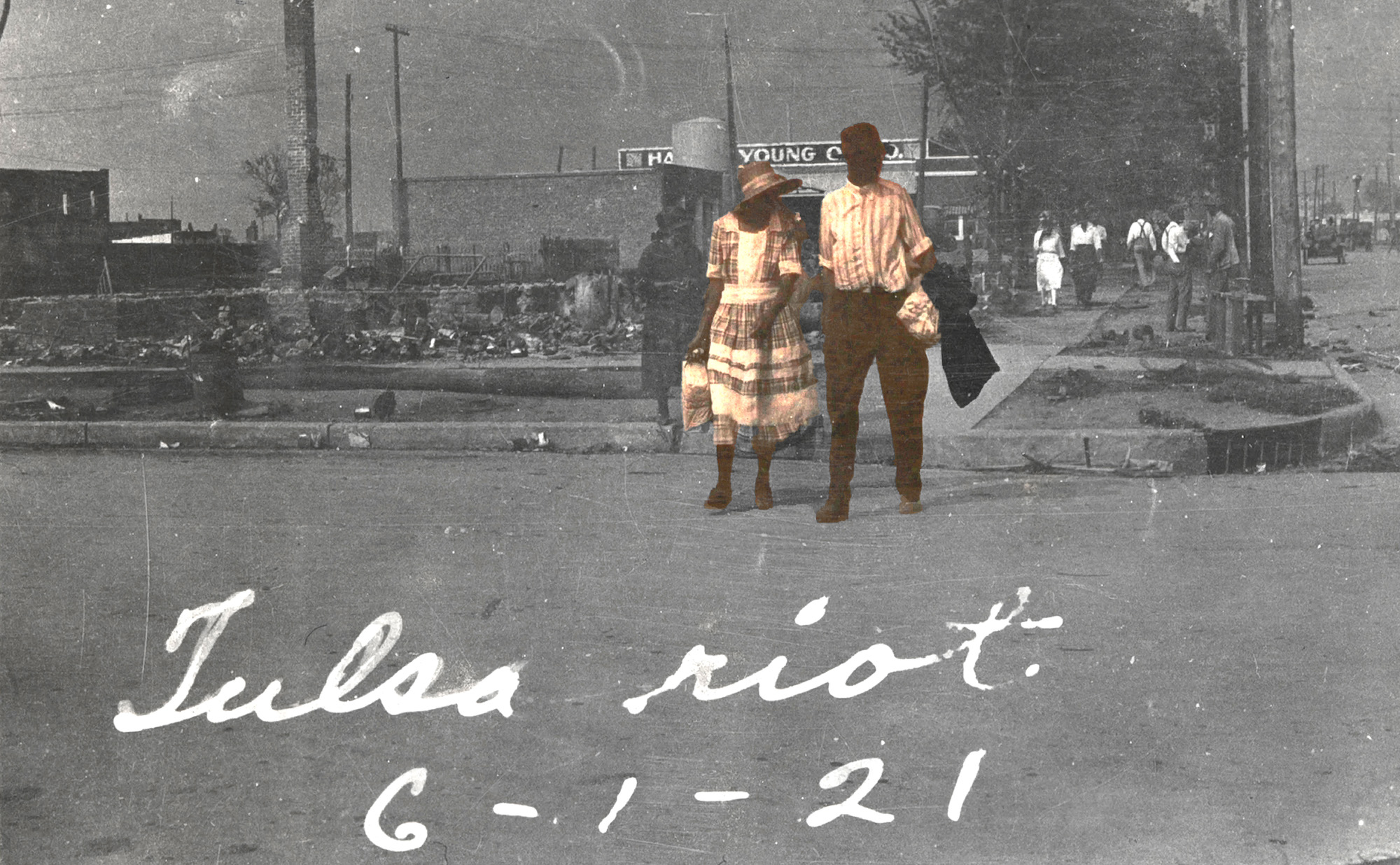

A black couple walks across a street with smoke rising in the distance after the 1921 Tulsa race massacre. Oklahoma Historical Society and The Oklahoma Eagle.

Some government officials are finally acknowledging and engaging in the conversation about racial injustices and inequality faced by Black Americans—and a few states are implementing reparations efforts.

Over the years, federal reparations efforts in the United States have lagged in Congress. After the nation elected its first ever Black president in 2008, and more than 400 years since the first recorded arrival of enslaved African people in the U.S., some government officials are finally acknowledging and engaging in the conversation of racial injustices and inequality faced by Black Americans—and a few states are implementing reparations efforts.

Reparations address wrongdoings and harm such as slavery and segregation and provide compensation to those whose families experienced or have been affected by such injustices.

Tensions surrounding the country’s history of racial violence and mistreatment of Black people in America reached a fever pitch in 2020 when video footage of policeman Derek Chauvin murdering George Floyd circled the globe, further fueling discussions about what actionable measures could be taken to make reparations a reality.

For California Secretary of State Shirley Weber, Floyd’s death signaled “a tipping point.” As an assembly member representing San Diego in September 2020, Weber put forth a bill that established a nine-member reparations task force—the first-ever in the country—which was signed into law by California Gov. Gavin Newsom. But the state of California didn’t stop there.

In June 2022, LA County officials moved forward to remedy historic injustices and voted to return beachfront land taken from married couple Charles and Willa Bruce in 1924. Bruce’s Beach, Manhattan Beach’s oldest beachfront, was purchased by the Bruces in 1912 to establish a resort for Black families during the segregation era. Kamilah Moore, an attorney and chair of California’s Reparations Task Force, was pleased with the outcome.

“I am incredibly proud of California and the LA County Board of Supervisors for returning their oceanfront property to the Bruce family,” Moore told Stacker. “Having their oceanfront property returned to them nearly 100 years after it was seized is a form of reparations under international law. Under international law, there are five forms of reparations—consideration, restitution, rehabilitation, satisfaction, and guarantees of non-repetition.”

“The return of stolen land is considered reparations under the form of restitution because restitution accounts for stolen wealth and property—real or intellectual,” said Moore. “I hope that the return of the land to the Bruce family sparks a movement where African Americans receive their land back from any and all public, private, or otherwise entities that have been unjustly enriched by land theft.”

The country is striving to make changes on an international level as well. The U.S. is participating in the United Nations’ Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination taking place in Geneva, during which the committee will evaluate Benin, Nicaragua, Azerbaijan, Slovakia, Zimbabwe, and Suriname, as well as the United States to see how these nations are implementing the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

On the home front, Stacker examined state government records and news reports to find which states have taken action or are examining ways to make reparations to Black Americans.

Oklahoma

Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood was a thriving community built by Black people with an estimated 100,000 residents. The area was so prosperous that it was dubbed “America’s Black Wall Street.”

In 1921, however, tensions rose between Black and white communities over an incident between a 17-year-old white elevator operator named Sarah Page and a 19-year-old Black man, Dick Rowland. There have been several variations told of what actually took place, but the most common is that Rowland accidentally stepped on Page’s foot in the elevator, causing her to lose balance. When Rowland reached out to help break her fall, Page screamed.

Racial violence ensued, with several hundred people brutally killed and more than 1,250 homes burned down. The once-vibrant community that took years to build was wiped out in a matter of hours.

In May 2022, an Oklahoma judge allowed a lawsuit by the survivors of the incident seeking reparations for the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre to proceed. Reparations are also being sought out for descendants of those affected by the destructive rampage, which also left close to 10,000 people homeless.

California

The state’s recently created reparations task force made history as the first in the nation and in its interim report has referenced several instances where reparations would be appropriate. The task force has suggested that people who lost their homes to urban renewal initiatives, government seizure, or the construction of freeways should qualify for housing grants and loans with zero interest. A second report is due to the California legislature in July 2023.

Michigan

In January 2022, Rep. Cynthia A. Johnson introduced House Bill 5673, which called for $1.5 billion to establish a racial equality and reparations fund for the state of Michigan. This bill is one of three that lawmakers are hoping to bring together collectively into the Racial Equity and Reparations Fund Act. Johnson has said the bill would help to create financial opportunities for those who have historically been shut out or have been forgotten.

North Carolina

In 2007, the North Carolina Senate apologized for its role in segregation, discrimination, and other wrongdoings inflicted upon Black Americans. In 2020, the city of Asheville apologized for its role in slavery, and in June 2022, the Asheville City Council went even further, approving a budget of $2.1 million to fund reparations initiatives. The allotted funding stems from land purchased dating to the 1970s for the city’s urban renewal programs, which negatively affected Black families.

Illinois

Evanston, Illinois, an affluent northern suburb of Chicago, made history in March 2022 by becoming the first U.S. city to provide reparations to its Black residents. Evanston City Council members voted 8-1 to provide $400,000 to 16 eligible Black households, which would each receive $25,000 toward housing assistance or a down payment on a property. The city’s Local Reparations Restorative Housing Program dispersed these funds to the first round of families in May 2022.

Maryland

In 2021, residents of the small town of Greenbelt, Maryland, voted in favor of creating a commission to study reparations and the possibility of compensation to Black and Native American families in the area. Greenbelt was built in the 1930s by both African American and white workers. Although some of the land was occupied by Black farmers and many Black Americans helped to build the town, Black people were prohibited from the community, which became segregated and welcomed only white families.

The Maryland Reparations Commission began holding discussions in early 2022 in an effort toward offering some sort of compensation to descendants of individuals who were enslaved in the state.

Iowa

Iowa outlawed slavery in 1846, the same year it attained statehood. But it was not until 2003 that some small effort toward reparation would be made in the Iowa House of Representatives, which adopted House Res. 29. This resolution encouraged the insurance commissioner to request “records of any insurance policies issued by an insurance company or a predecessor company during the slavery era providing coverage to a slaveholder for damage to or death of a slave.”

Alabama

In 2007, Alabama’s Republican Gov. Bob Riley formally apologized for the state’s role in slavery and signed a resolution of “profound regret” for the longtime effects the system of slavery had on the nation. Since the apology, there haven’t been any actionable state-led initiatives proposing reparations, but the apology may have left some room for future discussions.

Connecticut

The state of Connecticut abolished slavery in 1848, becoming the last state in the New England area to do so. In 2021, Rep. Anthony Nolan put forth to the state’s general assembly proposed bill 6267, which would create a task force to analyze racial inequity and inequality.

Delaware

In February 2016, Gov. Jack Markell acknowledged the state’s role in years of racial oppression and apologized via a formal resolution. While the apologetic gesture may seem insignificant, as no further formal actions have been taken, it does represent an opening salvo to potential discussion.

Delaware, commonly referred to as “The First State,” was one of the first 13 states to sign off in agreement with the U.S. Constitution. It was, however, also one of the last states to abolish slavery, waiting over 30 years after the Civil War to ratify the 13th Amendment.

Florida

In 1923, a white woman claimed to have been attacked by a Black man, which resulted in her husband gathering white residents to hunt him down. Violence erupted in the small, predominantly Black town of Rosewood, where the white mob burned down several buildings and slaughtered animals, causing residents of the central Florida community to flee into nearby swamps and other Florida cities such as Gainsville. Consequently, the once-prosperous Black town of Rosewood was deserted.

In 1994, the Florida state legislature passed House Bill 591, which provided payment to survivors and descendants of the Rosewood massacre. While checks were issued to many actual survivors of the massacre in late 1994 and early 1995, according to a report by The Washington Post, by the time these individuals’ family members—some 143 descendants—received checks from the state, only half received just over $2,000. Thereafter, a scholarship fund was established for descendants of Rosewood victims.

New Jersey

In 2019, after years of trying, members of the New Jersey Black Caucus introduced a bill to call for a task force to be established that would review New Jersey’s history of segregation and study the needs of New Jersey residents who are descendants of enslaved people. Unfortunately, it did not pass.

In 2022, the Reparations Task Force bill was reintroduced by a trio of assemblywomen. Newark Mayor Ras Baraka has expressed support for the bill and even acknowledged that Bergen County was one of the major slave-holding counties in the state.

Tennessee

In April 2021, the U.S. House Judiciary Committee advanced efforts to approve a bill that would form a commission to study the lasting effects of slavery. Tennessee Rep. Steve Cohen cosponsored the bill, which was introduced by Texas Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee.

Such support from a Tennessee legislator is a long way from 2014, when the state House voted to express “profound regret” for slavery but not apologize.

Virginia

In 2021, Gov. Ralph Northam signed a bill that would call for universities within the Commonwealth to create scholarships for descendants of enslaved people. The Enslaved Ancestors College Access Scholarship and Memorial Program requires all institutions that benefited from the labor of enslaved people to provide scholarships or economic development programs for people in special communities.