By LIONEL RAMOS AND REBECCA NAJERA, OKLAHOMA WATCH

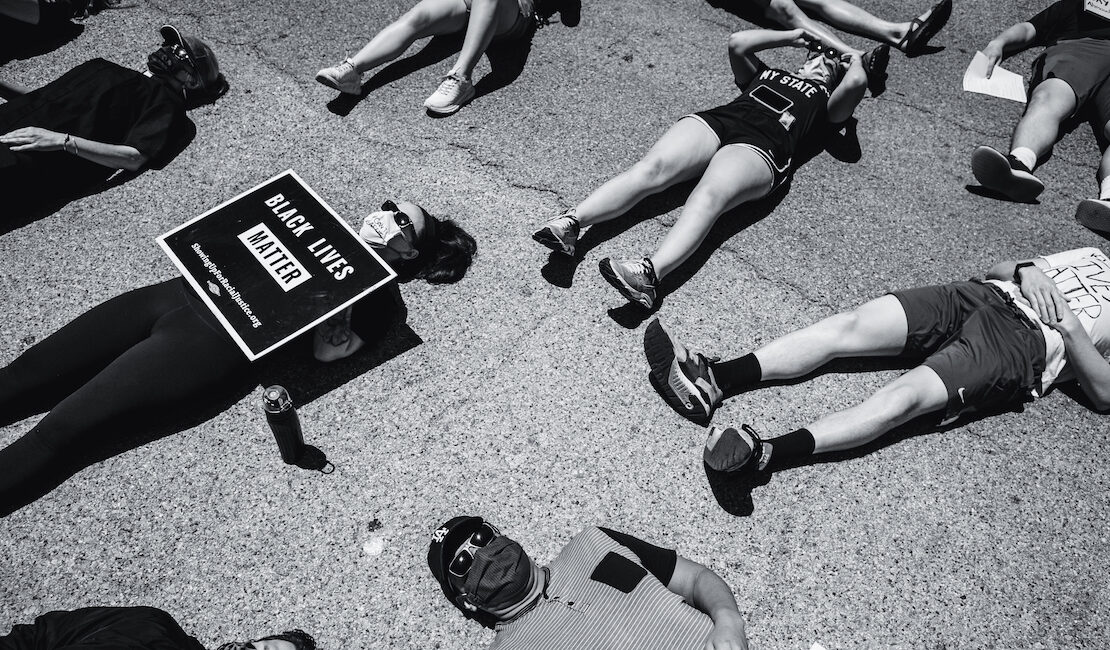

George Floyd’s murder by a Minneapolis police officer and the resulting nationwide protests led some states to create commissions to examine racial disparities and propose solutions. Other states had them prior to Floyd’s May 2020 death.

Oklahoma State Sen. George Young (D-Oklahoma City) has proposed similar legislation multiple times, failing again to receive a committee hearing this session.

Senate Bill 1204 proposes creating a 30-member Oklahoma Commission on Race and Equality. The governor and majority leaders of the Senate and House would each appoint seven members. The Oklahoma Legislative Black Caucus would appoint nine.

The commission would meet at least six times annually to allow Oklahomans to raise issues, complaints and proposals relating to racial bias and discrimination. Its duties would include monitoring legislation for potentially discriminatory aspects.

The Republican super-majority in the Legislature last year passed laws limiting instruction about race and gender in public schools — which the American Civil Liberties Union is challenging in federal court — and increasing penalties for demonstrators who block public roadways. That law also gives immunity to motorists who while attempting to flee unintentionally injure or kill protestors.

In March, Oklahoma became the 13th state to ban transgender athletes from playing on female sports teams when Gov. Kevin Stitt signed a bill into law.

Young said he frequently hears from constituents who complain of unfair treatment or injustices in dealings with law enforcement or state agencies.

“That’s what the piece of legislation is about, is giving voice to those individuals,” Young said.

‘What Are Those Things Creating Disparities’?

Damion Shade is the justice and economic mobility project manager for Oklahoma Policy Institute. He worked with Young to provide data and research supporting the need for a race and equality commission.

As of June 2020, the incarceration rate for Black Oklahomans was five times that of white Oklahomans.

“It would be almost impossible to truly understand Oklahoma’s incarceration crisis without looking through the prism of race,” Shade said. “Oklahoma’s incarceration disparities with the rest of the United States are almost entirely accounted for by racial disparities.”

One in five Oklahoma children lives in households with an income of $25,926 or less for a family of two adults and two children, according to the Oklahoma Policy Institute. Black children are about six times more likely to live in poverty. Hispanic and Latino children are four times as likely and Native Americans are twice as likely.

“We often think of racism and systemic racism as an experienced thing. A certain person has racial animus towards someone else,” Shade said.

“One of our big points with the data and why it’s so important to do this type of really detailed analysis is in the situation of (court) fines and fees, no police officer would ever need to have a personal animus against a Black person to disproportionately target them for arrest, a stop or search. They are simply going where the failure to pay warrants are.”

Shade points to an Open Justice Oklahoma examination focusing on the north Tulsa ZIP code of 74115, where residents had a combined court debt of more than $11 million. Nearly 20% of residents had failure-to-pay warrants.

The state’s uncollected court debt from 2012-18 totals more than $630 million.

“If the court fines and fees are being disproportionately assessed to the poorest community which — because of racial wealth gaps in large urban centers — happen to be the black and brown communities, that’s where the cops are naturally going to go,” Shade said.

“It doesn’t require racial animus. It just requires the system to have been constructed poorly.”

Having a commission on race and equality would provide a platform for these issues, he said.

“The idea is to be able to look at those differences and try and account for what’s doing them,” Shade said. “When so many of the poverty metrics and other statistics look roughly analogous, what are those things that are creating disparities?”

Javier Hernandez was once in the federal Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program and eventually earned his green card. Hernandez, who works as an attorney in Oklahoma City, said the Hispanic population in Oklahoma is a large economic driver in the state. A race and equality commission would allow Hispanic entrepreneurs’ needs and issues to be considered in state-level legislation, he said.

There are nearly 20,000 Hispanic-owned businesses across the state, according to the Greater Oklahoma City Hispanic Chamber of Commerce’s website. That number is growing, fueled by a 42.1% increase in the state’s Hispanic population since 2010.

“More than anything, I think it’ll help create a bridge between people who seem out of reach of each other. A commission like that would help bridge the community to those top-level legislators,” Hernandez said.

Dawn Stover leads the Alliance of Tribal Coalitions to End Violence, an organization working to increase awareness and response to violence against native women. She said a race and equality commission could address the high rates of sexual assault and violence against native women — and women of color.

“The idea that we wouldn’t have a race and equality commission for the state of Oklahoma is basically saying, to certain subsets of our citizens, ‘you don’t matter,” Stover said.

Young’s bill has been pushed from the Senate General Government Committee to Appropriations and finally to the Judiciary Committee. Multiple calls to the offices of Sen. Tom Dugger (R-Stillwater) and Roger Thompson (R-Okemah) who lead the General Government and Appropriations committees, respectively, went unreturned. Sen. Brent Howard, who chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee, was unavailable due to a death in his family.

State Sen. Michael Brooks, D-Oklahoma City, said he is unfamiliar with SB 1204 because it was never heard by his Senate Judiciary Committee. “Unfortunately, it’s at the discretion of the chair what bills get heard,” Brooks said. “Even members of the committee may have input, but they don’t ultimately make the decision.”

House Rep. Regina Goodwin, D-Tulsa, co-authored the bills. Without a vote or hearing, the public has no idea where lawmakers stand on a bill.

“If it had gotten a hearing in the committees, they would’ve documented the vote,” she said.

What Other Commissions Look Like

Oklahoma once had a Human Rights Commission, established in 1963 around the time Martin Luther King Jr. led the march on Washington D.C and delivered his “I Have A Dream” speech. That commission was dissolved and merged with the attorney general’s office in 2013, largely because in its previous six months the commission had reached a new level of inactivity.

The Oklahoma Attorney General’s Office of Civil Rights Enforcement primarily accepts, serves and reports on complaints of racial profiling and discrimination by state law enforcement. Its attorneys train public and private entities on topics like sexual harassment, civil rights enforcement and equal opportunity employment.

According to that office’s Jan. 31, 2021 report, 11 complaints were made in 2020. One was pending when the report was published, three were deemed to have “no cause” after an agency’s internal investigation, and seven were “not applicable” because the complaints were made against state agencies that are not considered law enforcement.

Six complaints from 2019 carried over into 2020. Four of them were deemed to have no cause and two were still pending. Data from 2021 is unavailable.

Since 2000, Oklahoma has had a law banning law enforcement from racial profiling. The number of officers punished for the crime is virtually zero in a state that from 1980-2019 saw some of the highest levels of violenceagainst non-Hispanic Black people by police officers when compared to states like Nevada, Nebraska, Iowa and Kansas, which also had high rates.

Connecticut, Iowa, and North Carolina are among the states that have established race and equality commissions.

Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly established the Governor’s Commission on Racial Equity and Justice to study related issues in 2020. Legislation has been passed based on its findings, including a law that requires the Kansas attorney general to coordinate training for law enforcement regarding missing and murdered Indigenous people.

Dr. Tiffany Anderson, one of two co-chairs for Kansas’ commission and the superintendent for Topeka Public Schools, said progress takes time.

“We did not get into a situation of having a disproportionate number of black and brown people incarcerated (and) a disproportionate number of people in poverty in the marginalized (community) that are facing barriers related to equity and justice — we did not get there overnight. So we’re not gonna get out of it overnight,” Anderson said.

“We’re going to have the conversation and begin to learn how to transform where we are and in whatever space that you are in, you have the power to do that, whether it’s to bring a bill — whether the bill passes or not, it’s the conversation about the bill. That’s part of the important piece.”

Lionel Ramos is a Report for America corps member who covers race and equity issues for Oklahoma Watch. Contact him at (210) 416-3672 or lramos@oklahomawatch.org. Follow him on Twitter at @LionelRamos21

Rebecca Najera is a Report for America corps member. She graduated with a master’s degree in journalism from the University of North Texas in 2021. Reach her at rnajera@oklahomawatch.org or (903) 808-0314. Follow her on Twitter @RebeccaNajera42.