By VICTOR LUCKERSON

The drawing was held on the night of Aug. 18, 1933, just like always. That evening, it happened in a nondescript two-story building located at 751 Greenwood Avenue, just a couple of doors over from Lynn Holderness’s dry cleaners and Fred Boston’s restaurant.

Inside, people recited back to themselves the numbers they hoped would be picked, the sequence of digits that would shower them with fortunes–or at least enough money for a carefree night pinballing between the neighborhood choc joints. The Great Depression was dragging into its fourth year. Those years had inched by even slower for Tulsa’s Black workers toiling under the maxim “last hired first fired.” Everybody needed a win.

Sometime before 11 p.m., one of the people in charge of the drawing fished twelve small capsules out of a pasteboard bucket about the size of a quart of ice cream. Each capsule contained a slip of paper with a figure between 1 and 78. The twelve figures were scrawled on a blackboard. The winning numbers. A lucky person or two might have “hit” right then and there at the policy wheel headquarters, yelping in exaltation and demanding their payout. But showing your face around a policy wheel was a dicey proposition. The game was illegal, after all, and subject to regular raids by police and intermittently “tough-on-crime” mayors. Most folks would wait for the foot-soldiers of the operation, known as numbers runners, to spread the news of the winning numbers through the neighborhood via small sheets of paper called policy slips. Every regular player had their own personal runner, who recorded their bets and hand-delivered their prizes.

Everyone called him Whitey

It was Elmer Payne, though, who would ultimately win more from the game than any hopeful bettor. Payne was the operator of the lottery-like gambling establishment at 751 Greenwood, known as a policy wheel. That meant he took home the lion’s share of the business’s profits. Though during the day, he worked as a driller in the oil fields outside Tulsa, at night he became Greenwood’s Policy King. Elmer lived about four miles west of the neighborhood, and his regular presence in city’s only Black enclave was conspicuous because of his skin color. Everyone simply called him “Whitey” Payne.

After the game ended on that Friday evening, Whitey stepped out into the muggy summer night. The streets still buzzed with people sauntering down sidewalks. Cars eagerly cruised to their weekend destinations. Greenwood never slept in those days. If the law rolled by, Whitey didn’t need to worry too much. Rumor was he’d already paid the police off well to their satisfaction.

Just moments after Whitey exited the gambling hall, two Black men, one short and one tall, stepped out of a car hidden in an alley just down the street. They moved with decisiveness, clutching pistols at their sides. As a bus roared past on Greenwood Avenue, they lobbed a hail of bullets at Whitey, their gunshots melding with the roar of the engine. Whitey’s brother, who had walked outside with him, returned fire and shot one of the men in the abdomen. The two assailants quickly dove back into their car and sped off north, bullets whizzing through the air all the while. A state prosecutor would later claim the whole affair was “carried out in true ‘gangster’ style.”

After a bullet entered his body through his upper back and exited through his chest, Whitey Payne lay sprawled out in a bloody pool on the street. The Policy King–one of them, at least–was dead.

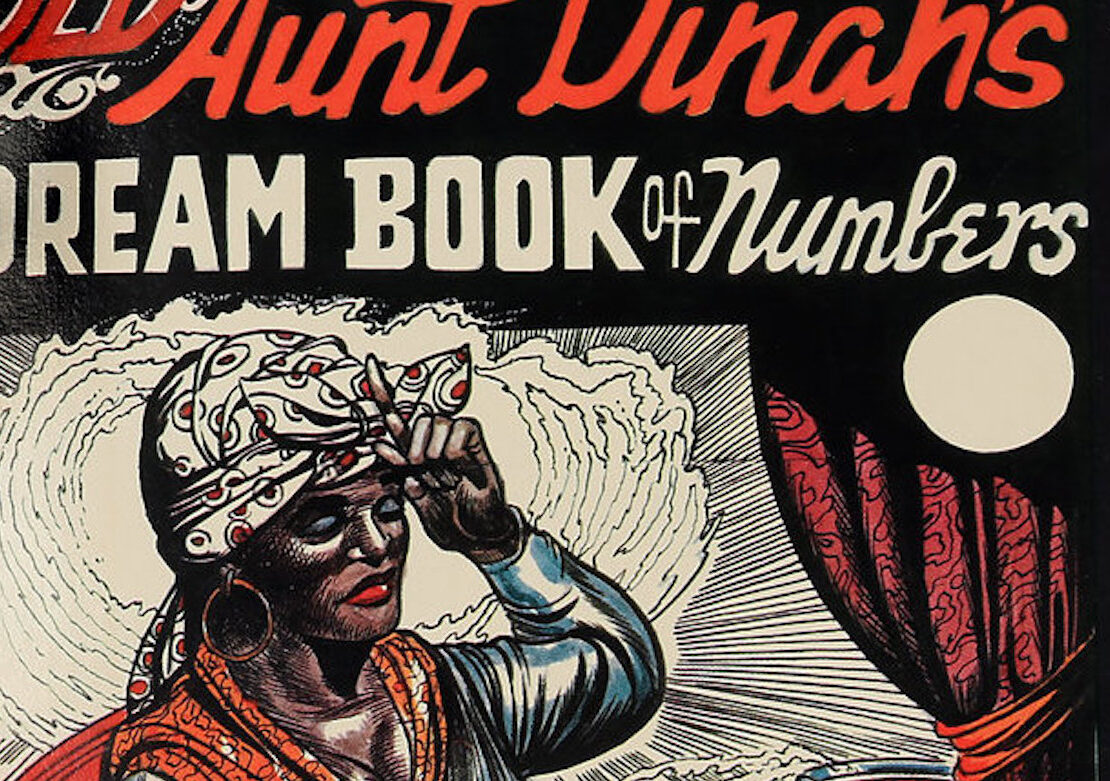

People who played policy (or “the numbers”) often purchased dream books like the one above, which promised to translate their nighttime visions into winning numerical picks

Like many so-called vices, playing the numbers was a common but demonized activity before the government figured out how to profit off of it (the rules largely mirror modern, state-backed lotteries). While the policy wheel had existed in many Northern and Midwestern cities since the nineteenth century, the Great Depression’s mix of economic desperation, political corruption, and sophisticated gang activity drove more people to both play and profit from the game. As policy grew in economic value, white gangsters like Whitey Payne began to encroach on what had long been a Black enterprise. Racial conflicts emerged in disputes over territory.

A national dilemma

The problem was a nationwide phenomenon. In Harlem, a Black Frenchwoman named Stephanie St. Clair, known as the “Queen of Policy,” staged a long, public battle against a white interloper named Dutch Schultz. She denounced him in the press, threatened white store owners who aided him and tried to rally Black policy operators to form a larger, more powerful syndicate. In Chicago, a Black family of brothers named Edward, George, and McKissick Jones turned the South Side into a policy boomtown in the 1930s. They were muscled out by The Outfit, a mafia gang originally run by Al Capone. Edward was kidnapped by white gangsters and held on $100,000 ransom; McKissick died mysteriously in a car accident. In many cities, white mayors oversaw the aggressive prosecution of Black policy operators in order to short-circuit Black economic and political power. Congressman William Dawson of Chicago, who viewed Black policy operators as part of his political base, vowed that he would “make it his business to keep the white syndicate out.”

In Greenwood, Whitey Payne’s fiercest rival was a Black-owned drug store by O.C. Foster. Born in 1890 in Texas, Foster arrived in Tulsa in the 1910’s and worked as a janitor before opening his first store in Greenwood in the mid-1920s. By the 1930’s, it was common knowledge in the neighborhood that his other main business was gambling. “He had a fleet of 31 cars to pick up policy money and bring it to his drugstore,” recalled Waldo Jones, Sr., a prominent Greenwood attorney. “He’d have maybe a thousand or two thousand dollars in his pocket, all the time. There was about $10,000 in his safe at the drugstore most of the time. I stayed there at night to take care of the place.”

Within hours of Whitey Payne’s killing, O.C. Foster was arrested as a prime suspect. Two months later, he was indicted on a murder charge, accused of hiring three other men–Buddy Jones, Lester Swannegan, and James Hollis–to carry out the attack. Swannegan was the one who was shot at the scene of the crime; he died days later. Hollis, meanwhile, flipped and turned state’s witness following his arrest. Testifying on behalf of the prosecution, he painted Foster as a decadent man with a taste for double-breasted blue suits and yellow Buick coupes, a man who spent the entire summer obsessed with killing Whitey Payne.

The plot against Whitey

In Hollis’s telling, he and Foster traveled to Kansas City in July to get a bomb from a group of Italian mobsters so they could blow Whitey’s gambling hall up with him still inside it. But they were forced to abandon the plan when they were pulled over by police while the bomb was in their car. Foster was shaken down for a bribe to avoid being arrested. Later, according to Hollis, Foster decided to use gunmen to execute the hit, agreeing to pay them $500 if they pulled it off. Foster felt his policy operation was facing constant scrutiny from police while Whitey was free to build a gambling empire, Hollis claimed. “We will get that son-of-a-bitch tonight,” Foster allegedly said on the day of the murder, “if I have to go along too.'”

O.C. Foster categorically denied any involvement in Payne’s murder or a scheme to bomb his business (he did plead guilty to operating a policy game earlier in the year). He was represented in the murder case by none other than B.C. Franklin, the famed Greenwood attorney who had defended Black landowners from craven white real estate developers after the 1921 Race Massacre. In a legal brief, Franklin dismissed Hollis’s testimony as, “unreasonable, preposterous, and absurd.” In his autobiography, Franklin wrote that policy operators in Kansas City, where Hollis was from, had likely plotted to both murder Payne and frame Foster for the killing. It would have been a cold and clever way to eliminate much of their potential competition in Tulsa with a single bullet. Franklin believed Foster was telling the truth after interviewing him, and became more sure after a trip to Kansas City to interview some of the mysterious figures floating around the case. He thought racism was clouding Tulsa county prosecutors’ assessment of the facts. “The assistant county attorney was grimly enjoying every minute of the sordid spectacle and the prospect of Foster’s being thrown to the lions,” Franklin wrote later. “[The case was] an example to all colored men that, under no circumstances, should they ever kill a white man in Tulsa County.” Franklin also filed a motion in the case arguing that Foster was being discriminated against in the selection of an all-white jury for the trial.

Foster acquitted

In February 1934, after nearly nine hours of deliberation, a jury acquitted O.C. Foster on the murder charge. The case and Franklin’s advocacy helped crack open the door for Black Oklahomans to sit on juries in future trials. Foster, meanwhile, left Tulsa not long after his acquittal to open a billiards parlor in Chicago. Stories passed down in Greenwood said he tried his hand at running the numbers up north too, but by then white mobsters were already seizing control of the biggest business enterprise in the Black economy. “He stayed there maybe seven or eight years,” Waldo Jones recalled. “They found him dead. I don’t know the circumstances surrounding his death.”

As for gambling in Greenwood, a new Policy King stepped in to take Foster’s place. Then another, and another. The game would be a community staple, legal or not, for decades to come.

Victor Luckerson is a writer based in Tulsa working on a book, “Built from the Fire,” is a narrative history of Black Wall Street in the Historic Greenwood District, told through the eyes of four generations of one resilient family. For more of Luckerson’s writings, subscribe to: Run It Back@substack.com