ABOUT THIS SERIES

The Oklahoma Eagle’s “Of Greenwood” series is part of our 2nd Century Campaign, which commemorates the hundredth anniversary of this African American newspaper. This series is made possible through our partnership with Liberty Mutual Insurance.

By Gary Lee, The Oklahoma Eagle

Photography by Basil Childers

The Frazier family’s business dream started with ketchup. Most people use the tomato condiment to doctor up either a hot dog, hamburger or to smother fried potatoes. But the Frazier’s looked at a bottle of Heinz 57 and saw something more significant – the base for a product that could eventually give them multigenerational wealth.

So, Eric Frazier, the middle son, put some ketchup in a pot. He added spices, starting with the ingredients of secret barbecue rub that his dad, Ellis Frazier II – the family patriarch – had used for decades. Eric and his brother Ellis III tinkered with the recipe. Several months later, they came up with an honest to God-slap-your-mama barbecue sauce. They named it, Barbara Q., after their late mother.

And just like that, Barbara Q. has become one of the newest in a long line of Black-owned businesses in North Tulsa. It comes in two sweet and hot versions. Both have their followings. The enterprise is a family affair, with Frazier II and his sons Ellis Frazier III., Eric and Bryan, and daughter Allis all in as co-owners. They commissioned S.S Foods Inc., a Mustang, Oklahoma-based company, to bottle it up at 30 cases a time. Several Tulsa area stores offer bottles at around $5 apiece, including the new Oasis Fresh Market on North Peoria and the Corner Store on Greenwood Avenue.

Three years into the hustle, 75-year-old Ellis Frazier II acknowledges that the business is “just about halfway breaking even.”

But his ambitions remain high. “I would like to see it get busy enough that we eventually have our place for manufacturing and distributing,” he said.

In his dreams, Barbara Q. will become a multigeneration business where “all of the kids and grandkids could be taken care of.”

Barbara Q. has made the Frazier’s part of a storied history of Black entrepreneurship in Tulsa dating back more than 120 years. In the early 1900s, Blacks started building the Greenwood section, a neighborhood of their own in a city segregated by Jim Crow statutes. The boom of stores, places of lodging, and eateries rose to become the “Negro Wall Street,” one of the most prosperous centers of Black commerce in the United States.

Massacre and destruction

The Race Massacre of 1921, in which a white mob destroyed the community, murdered as many as three hundred Blacks, decimated many of the businesses and drove some of the owners – such as famed developer O.W. Gurley – out of town.

A century after Black Wall Street burned, the sense of drive that created it still runs strong among North Tulsa’s Black entrepreneurs.

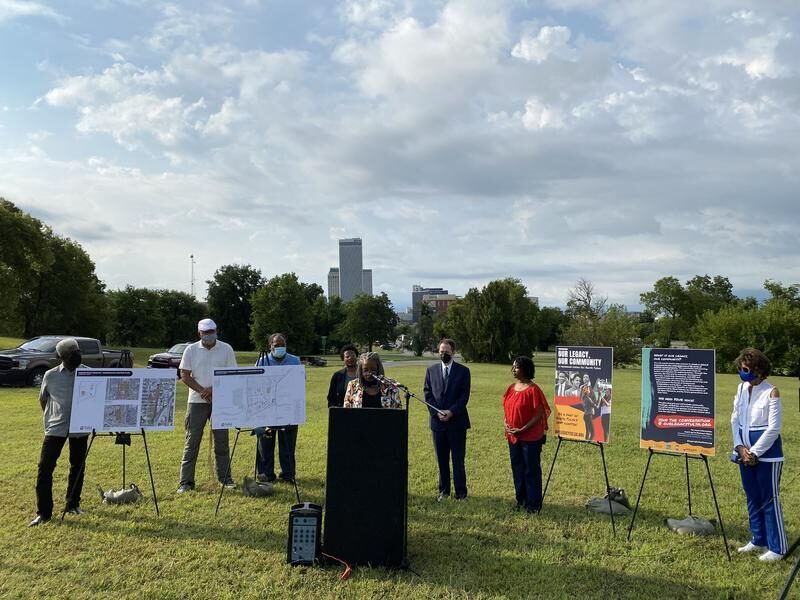

As the doors of one Black business close, others open. Earlier this summer, Antoine Harris, an African American developer, announced plans for a $75 million boutique hotel and mixed-use complex on 22 acres at 36th Street North and MLK Jr. Boulevard in North Tulsa.

“Black folks are entrepreneurial by nature,” said Onikah Asamoa-Caeser, owner of Fulton Street Books and Cafe, a North Tulsa store specializing in books by authors who are Black, Brown or from other underserved communities.

“The added layer in Tulsa is that the city does have a blueprint for Black business success,” she said. “If you are someone who believes in a higher calling, in building on history, you feel that vibe here.”

Mikeal Vaughn, founder of Urban Coder’s Guild, a nonprofit dedicated to educating a new generation of Black and Brown tech leaders in Tulsa, concurs. “There is something about Tulsa that gives Black business owners inspiration and perseverance,” he said.

Asamoa-Caeser and others offer different reasons for the staying power of Black entrepreneurship in Tulsa. One is a homegrown resilience to make things work despite challenges. Another is a camaraderie among Tulsa’s Black business owners, helped by the 83-year-old Greenwood Chamber of Commerce and other alliances.

But the most prominent characteristic found in all the most successful of Tulsa’s Black entrepreneurs is their skillful use of personal diplomacy as a sales tool. All of the most resilient of Tulsa’s Black business owners become skilled ambassadors for their products in the community.

Since opening her first restaurant in North Tulsa in the early 1980s, Wanda Armstrong’s engaging manner with customers has helped make her known as the lady who serves up the best soul food in town.

James O. Goodwin, for five decades the publisher and public face of The Oklahoma Eagle, North Tulsa’s 100-year-old weekly newspaper and one America’s oldest Black-owned publications, has become a synonym for reliable news coverage.

In a community where the shadow of trauma lingered long after the massacre, North Tulsans came to trust these business owners and whatever they were selling.

A Post-massacre comeback

The biggest testament to Tulsa’s Black entrepreneurs was the comeback they navigated following the 1921 Massacre.

After the blood dried and the dust settled, a small business owner in just about every Black Tulsa family sprang forward. They opened new rooming houses, transport companies, cafes, juke joints, and other enterprises at an extraordinary pace. By the mid-1940s, by the account of Oklahoma Historical Society, there were 240 businesses packed along with a few blocks of the Greenwood section. This was the second wave of Black entrepreneurship in Tulsa.

In the 1950s, Ellis Frazier Sr., father of Barbara Q co-owner Ellis Frazier, joined the party. He opened Ellis and Edward a small eatery at the corner of Greenwood Avenue and Easton Street. Fried chicken and hamburgers were specialties. Ellis II, who was nine years old, sometimes worked in his father’s garden and helped around the restaurant. Looking back, he feels the experience may have given him the business owner’s bug.

By the 1960s and 1970s, civil rights laws allowed Black Tulsans to shop in white-owned stores. Black customers began to favor white-owned stores. Urban Renewal – and the construction of the Crosstown Expressway – took the heart out of the Greenwood community. Banks tightened their control of capital support for Black businesses. The spirit of Black ownership in Tulsa began to dampen.

The third wave

In the 1980s and 1990s, a new generation of small business owners came on strong. Howard and Fred Grimes opened Mantique, an upscale clothing store in the Northland Shopping Center. Elmer Thompson founded Elmer’s, which would become a wildly popular barbecue restaurant.

These and other enterprises became mainstays in the third wave of entrepreneurship.

Buoyed by the excitement of the hundredth anniversary of the race massacre, the latest wave is still vibrant. But it differs from the previous eras in a couple of critical ways.

Black businesses represent a smaller footprint in Tulsa. While the city’s Black population has risen from around 9,500 in 1921 to over 62,000 in 2019, only 1.25 percent of its 20,000 businesses are Black-owned, according to a June 2021 report by the Washington, D.C.-based Brookings Institute. That study blames the loss of wealth in Tulsa’s Black community caused by the massacre and Urban Renewal. If Black people in Tulsa owned a representative share of the area’s businesses, by Brooking’s account, there would be nearly 1,900 new Black businesses with potential revenues of over $10 billion per year.

While the legacy of Black entrepreneurship inspires the Fraziers, they said making Barbara Q. work as a business is a day-to-day grind. Ellis Frazier II sees it as the common small business owner’s juggling act between maintaining a consistently high product level, keeping costs at a minimum, and marketing to as broad a public as possible.

All of the family, including cousins, nephews, and whoever else raises a hand, engages in these pursuits. Not long ago, a cousin near Houston, Texas, invited friends over to sample the sauce and offer suggestions for improvement.

Ellis II has been exploring the idea of switching from glass to plastic bottles to save on production costs. Ellis III is working on a plan to put the sauce in small packets – like ketchup provided at fast-food restaurants – for easy shipment to stores across the country.

Like his entrepreneurial colleagues, Ellis II focuses his marketing of Barbara Q. on personal salesmanship. His everyday attire, a T-shirt bearing a picture of Barbara Q., makes him a walking advertisement for the product. He keeps a couple of cases of the sauce in his car trunk just in case he can sell a bottle or two here or there.

So far, the Fraziers have avoided seeking assistance from the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce or other organizations. Still, they acknowledge that they could benefit from professional guidance. They are also actively seeking investors who can help them ramp up to the next level.

Serving North Tulsa for over a century

On a recent Tuesday morning, Terry Jackson held forth in a meeting with a family who had lost their patriarch. As the family sat around the dark wooden table at Jack’s Memory Chapel, where Jackson is manager, tears flowed, and emotions ran strong.

In his sonorous voice, the burly 50-year-old Jackson assured his guests that he would do all they could to see that their father “was carried home” with dignity. No sooner than he saw the family off, Jackson stepped into the cool, dark, embalming room to prepare the body of another patron to be laid in a casket.

These twin pursuits – consoling bereaved families and beautifying corpses – have made the Jacksons’ business – one of North Tulsa’s favored companies for laying families to rest for more than a century.

“We have been the place that people trusted,” said George Riley, Jack’s funeral director. “People in Tulsa are very personable. They have known all the folks who worked here as part of the community. And when they had a death in the family, they knew we would take good care of them.”

Since arriving at Jack’s as a 24-year-old in 1974, Riley estimates that he has helped bury more than 8,000 Tulsans and comfort their families. In more than 46 years with the company, he has become one of the faces North Tulsans associate most closely with Jack’s.

The Jacksons’ funeral business is one of two original Black-owned businesses that have survived from the pre-massacre era to the current day. (The Oklahoma Eagle is the other legacy business that salvaged the printing equipment from the destroyed offices of the Tulsa Star to continue publishing a weekly newspaper in Greenwood.) The arc has made the Jacksons a part of the three waves of Black business entrepreneurship in Tulsa and a case study in a multigenerational Black family enterprise.

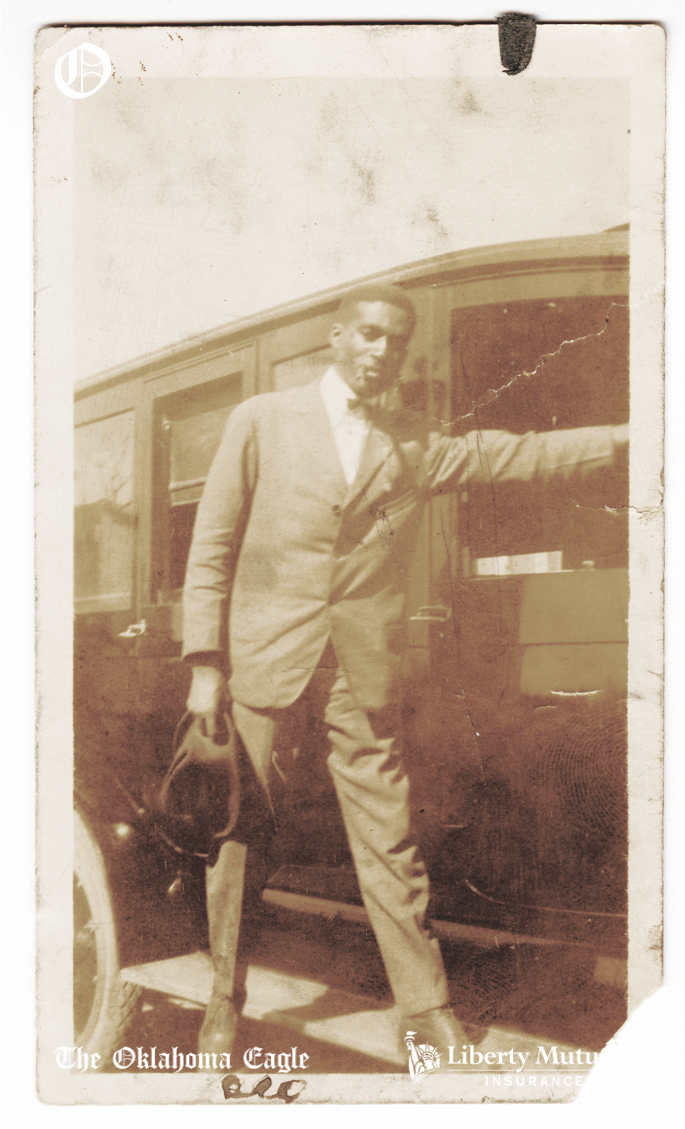

Samuel Malone Jackson, Terry’s grandfather known as “S.M.,” launched the family into the Greenwood community in 1917. With partner James Henri Goodwin, the 23-year-old entrepreneur and funeral home owner from Water Valley, Mississippi, they opened Jackson Undertaking Company in 1917, on 617 East Archer St.

S.M.’s charm and easy way of connecting with Black Tulsans made the business a go-to place for the Greenwood families to turn to for funerals.

The 1921 massacre destroyed the company, but S.M. quickly rebuilt it as Jackson’s Funeral Home. In the mid-1940s, after a dispute with the co-owner, S.M. left Jackson’s Funeral Home and temporarily retired. Restless, he opened Jack’s Memory Chapel.

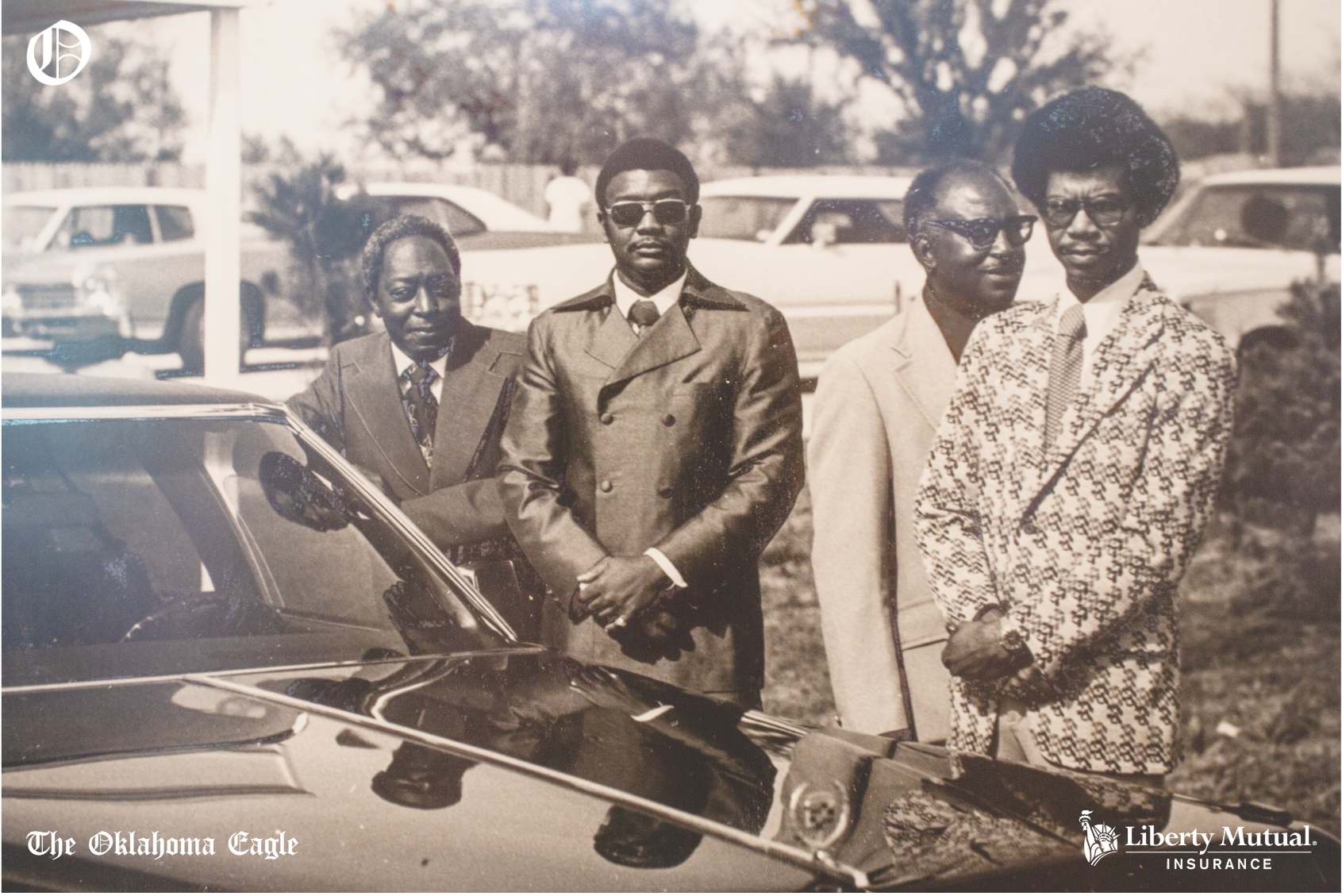

Together with his wife Eunice, the always dapperly dressed S.M. became a celebrated North Tulsa business figure. Based in the home the couple shared on East Marshall Street right off Greenwood Avenue, Jack’s would be one of the neighborhood’s high-profile enterprises. “People loved him,” Terry Jackson said of S.M. “And he loved them back.”

For all of his charisma, business acumen was not a strong suit for S.M. Unpaid invoices piled up so high that the family enlisted John Cloman Jr., a Chicago-based business executive, and Eunice’s brother, to clean up the books. Cloman relocated to Tulsa from Chicago in the late 1950s and put the business in the black.

Segregation’s ugly, important role

After S.M. died in 1975, James Black, a longtime business associate, ran the company. By the early 1990s, S.M.’s son Maurice took over. Maurice moved the business further north on East 36th Street North when the Greenwood neighborhood faded in the mid-1970s. It opened next to the aging but busy Northland Shopping Center complex. He successfully managed Jack’s until he died in 2020.

Segregation played a vital role in the business’s early success.

“Back in the day, if there were an accident involving a white and a Black, a white-owned ambulance would take the white and leave the Black laying there,” Terry Jackson recalls. “Whites didn’t do Black funerals. So, the business came to us.”

The undertaking was among the slowest industries to integrate into Tulsa. It was not until the 1980s that white funeral homes started reaching out to Blacks as patrons by most accounts.

Against that background, Black Tulsan’s loyalty to Jack’s was solidified. Jack’s buried dozens of North Tulsans a year, sometimes as a community service. From the 1950s through the early 1970s, Jack’s did many funerals for as low as $200. And some were conducted free of charge.

During the third wave of Black entrepreneurship in Tulsa, Jack’s rate of business has declined. In 1994, the company hit its peak, with an average of a service every day. In the past year, they performed an average of three a week. Prices range from $1,495 for a cremation to over $10,000 for a full no-holds-barred service with a casket.

As the business enters its second century, Riley is keenly aware of the challenges it faces. During an interview, he recounted some of them.

Tulsa’s Black community, once tight knit, has become more scattered, making marketing harder. New generations have brought competition, including Bigelow’s and Moore’s. The white-owned funeral homes, which once shunned Black customers, now jostle to get their business.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also brought dilemmas. While COVID-19 deaths have brought more business, the restrictions have made services intimate. Most importantly, clients are more cost-conscious, Riley said.

Through it all, Jack’s has stayed the course of its central mission to be of service to grieving North Tulsa families. Terry Jackson put it succinctly: “We exist to be there for people in their time of need, to help them through tough transitions.”

In training a younger generation of employees for careers in the funeral business, Jackson stresses the importance of the Golden Rule of Black Tulsa entrepreneurs: Engage in personal diplomacy. He tells trainees they can easily pick up business basics such as accounting and scheduling appointments, but what’s harder is learning to enter a situation and quickly assess who needs a hug and who needs a little distance.

“Being able to get that personal approach right is at the heart of what we do, and what we have done since the business began,” Terry Jackson said.

The fourth wave?

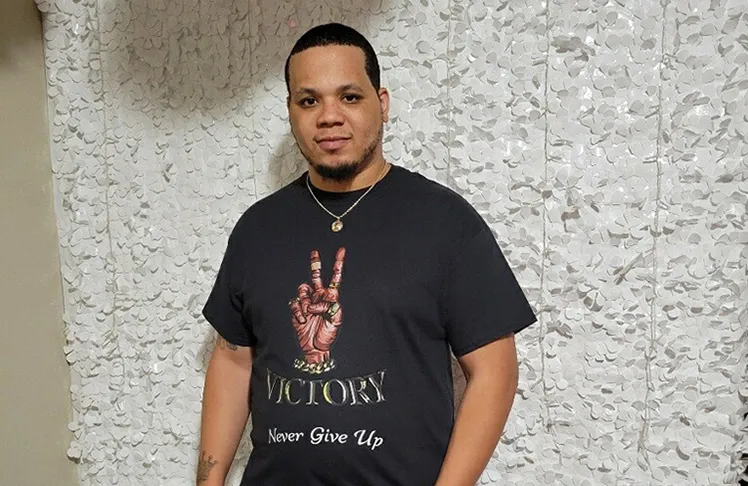

In his standard pitch to potential investors, Tyrance Billingsly II pays tribute to the dozens of businesses that helped create a legacy of Black entrepreneurship in Tulsa. But the 26-year-old North Tulsa native considers most of those enterprises’ relics of the past.

Billingsly is owner and creative force behind Black Tech Street, an aggregator enterprise focused on establishing Tulsa as a national center of tech enterprises, with a new generation of Black and Brown Tulsans at the helm.

“Within a decade, Tulsa can be a city known globally for its Black tech ecosystem,” Billingsly said in an interview. “We see the real possibility for every Black or Brown child in Tulsa to have the potential to make a global impact through the tech industry.”

So far, Billingsly said he has raised several million dollars to help fund BlackTech Street. If successful, the endeavor could be a central force behind the fourth wave of Black entrepreneurship in Tulsa.

Whatever the future brings, North Tulsa business owners and patrons agree on one thing: that entrepreneurship in the community will endure. “A lot of things are changing in the Northside,” said George Riley of Jack’s. “But this neighborhood is loyal to its business owners. And we are loyal to them. It’s hard to imagine one without the other.”