ABOUT THIS SERIES

The Oklahoma Eagle’s on the “Of Greenwood” series is part of our 2nd Century Campaign, which commemorates the hundredth anniversary of this African American newspaper. This series is made possible through our partnership with Liberty Mutual Insurance.

By Victor Luckerson, Special to The Eagle

Photography & Video by Basil Childers

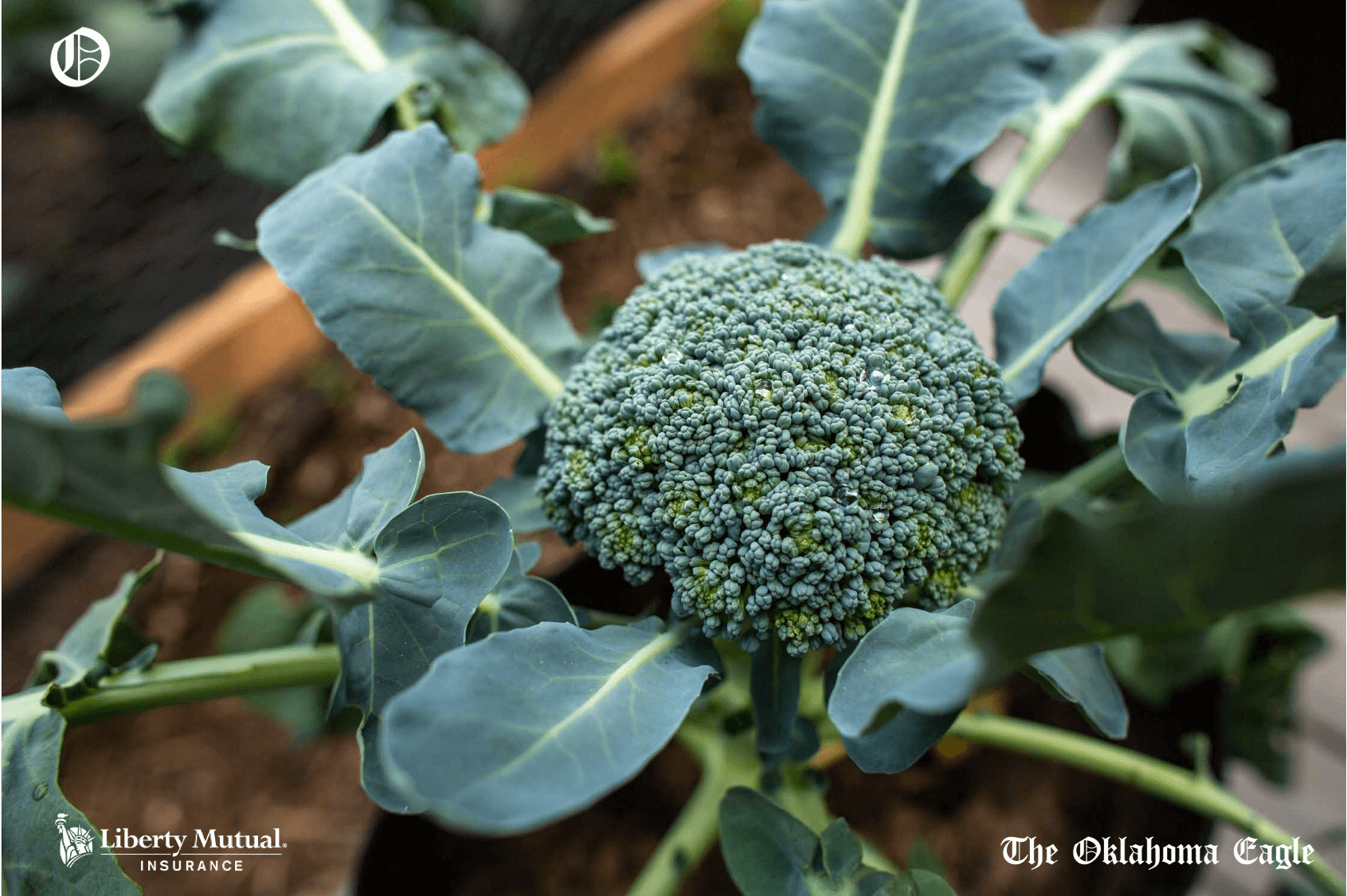

Behind a small light-green house on a cozy street in North Tulsa, Earl Stripling is tending to his own little Garden of Eden. Grapevines wind down metal trellises. In a small mesh greenhouse squeezed right into the middle of the yard, broccoli seeds germinate on an electric heat mat. More than 300 onions sprout from a flowerbed packed with phosphorus-rich soil. During a tour, Stripling speaks uninterrupted for ten minutes on soil technology and the earthy chemistry at play between phosphorus, nitrogen, and potassium. During the 2021 growing season, Stripling will raise more than 30 different types of fruits and vegetables, from hillbilly potato leaf tomatoes to turnip greens to bok choy. On this 50-by-70-foot plot of land, Stripling grows thousands of vegetables per year, a harvest he shares with family and friends by the basketful. Of course, he saves some of it to devour himself. “So basically,” he said after the tour, “that’s my whole little empire.”

Just a couple of miles northwest from Stripling’s edible paradise, Billie Parker is building her own elaborate farm. A hand-painted yellow and white sign reading “Community Pride Farmers Market” greets visitors as they turn onto her three-acre property. A 40-foot-by-70-foot “hoop house,” a more affordable version of a typical glass greenhouse, is easily spotted from the road. Parker, too, is gearing up for the new season. In early March, a freak, weeks-long deep freeze in Tulsa ruined some of her potatoes. She planned to convert them to compost. But inside the hoop house, she plucked a seed from a tiny, brilliant yellow flower that had not been deterred by the cold. “This is a mustard green,” Parker explained, “and this is a fresh seed.” Life finds a way in the soil, as it always has in North Tulsa.

By late Spring, Parker’s land will be overflowing with herbs, greens, radishes, strawberries, and other vegetables. “We need this–not only here,” she said, referring to her wonderland of a farm. “This is what we need on every corner.”

Stripling and Parker are tapping into a long legacy of agriculture and land ownership in North Tulsa, most famously epitomized by the iconic Greenwood District. For more than a century Black residents of Greenwood, North Tulsa and all of Oklahoma have had an intimate relationship with the land, drawing strength and sustenance from it. Today, in the wake of a pandemic and refocus on Black entrepreneurship, they – and others — are rekindling that passion.

Oklahoma’s Black Farming History

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, agriculture was one of the primary selling points to convince people to pack up their lives and venture to what was then known as the Twin Territories. Black boosters who wanted to attract more of their agrarian-oriented brethren out West were always sure to trumpet the richness of Oklahoma’s soil and the diversity of its harvest. In Langston, the all-Black town co-founded by the ambitious Black politician Edwin P. McCabe in 1890, the local paper promised not only a life free of white racism but also one of economic opportunity, provided by “a land of diversified crops.”

Some of this land was claimed by Black settlers in the federally organized land runs. Beginning in 1899, thousands of would-be homesteaders ventured to Oklahoma to claim a piece of the “Unassigned Lands” (the lands had been “assigned” to Native Americans as part of their removal to Oklahoma, then rescinded after the Civil War). By the time the runs were over in 1895, more than 13 million acres of land in the Twin Territories had come into settler ownership. Some of these settlers were Black, and came to be known as “state Negroes.” O.W. Gurley, the Greenwood pioneer most famous for being an enterprising merchant, was also a farm owner. He participated in the runs and staked a claim to land near the town of Perry, Oklahoma Territory. Cultivating the land was just as much a part of his pathway to wealth as later operating stores and hotels in the Greenwood District (Gurley also owned farmland in Arkansas and in Rogers County).

As settlers poured into the Twin Territories, the Blacks who had been there for generations–the formerly enslaved members of Native American tribes–were building up their own agricultural legacy. Early on, they farmed alongside Native Americans on communally owned land. During the land allotment process of the early 1900’s, when the federal government compelled the tribes to convert their land to a model of individual property ownership, the so-called Freedmen were granted more than 2 million acres of fertile soil and rushing rivers. It was the largest transfer of land wealth to Black people in the history of the United States. Many turned these allotments, which were as large as 160 acres, into thriving farms. A prominent Creek Freedman named A.G.W. Sango, for example, inherited his father’s cattle land and also cultivated his own land allotment.

Blacks around the country took notice of Oklahoma’s growing agricultural prosperity. When Booker T. Washington, the famed Black American educator and orator, visited Oklahoma in 1905, he admired the Black-owned farms surrounding the railroad tracks that cut through the countryside. He saw agriculture as the basic building block towards Black wealth, and saw Oklahoma as a great testing round for such endeavors.

“No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem,” he said in his famous Atlanta Exposition Speech in 1895.

Washington brought many more Black entrepreneurs to witness the bounty of Oklahoma when his National Negro Business League held its annual meeting in Muskogee in 1914. Washington was impressed by the industrial parade that bustled down Second Street and the ripe fruits shown off at a farmer’s exhibition in the convention hall. But he also saw there was much Black farmers could still do to improve their station. He said as much in his keynote address.

“Of the 20,000 colored farmers in Oklahoma, 13,000 of them are without livestock and 3,300 are without poultry on their farms. Get off the defensive and put the world to wondering how we have been able to secure so much livestock and poultry instead of so little,” he said. “There is no special color line in stock and poultry raising.”

The early twentieth century was a period when Black land ownership in Oklahoma peaked. According to the 1910 census, nonwhite farmers owned 1.6 million acres of land in Oklahoma, valued at more than $32 million (nearly $1 billion in today’s dollars). “There is no state in the Union where the Negro owns as much real property, and good real property, as he does in the state of Oklahoma,” the Muskogee Cimeter, a popular weekly newspaper, declared in 1917.

In Greenwood, farming played a key role in the neighborhood’s burgeoning vibrancy. Tulsa was primarily known as the “Oil Capital of the World,” but farming in the surrounding area contributed greatly to the local economy. In Wagoner County, which is just east of Tulsa, nearly half of the farmers who owned their own land were non-white. Some of these Black farmers lived in Greenwood or conducted business there. W.H. Smith, a fruit dealer in the neighborhood, bought a farm in Wagoner in the fall of 1918. He viewed the purchase as a bet on the future prosperity of Tulsa, and Greenwood in particular.

That prosperity was thrown into chaos in 1921, when a white mob set fire to 35 square blocks of Greenwood, killing as many as 300 people. But Greenwood residents rebuilt, and they emerged from their struggle with an even more vibrant community. When the Negro Business League returned to Oklahoma for its annual meeting in 1925, it chose not Muskogee, but Tulsa, as the new symbol for thriving Black entrepreneurship and agriculture in the state.

Reclaiming The Past

—

Earl Stripling first learned to farm at the corner of Cincinnati Avenue and Pine Street – the center of predominantly Black North Tulsa — in the 1960’s, in a massive garden tended by his uncle Merle Stripling, a firefighter who grew crops behind a pair of rent houses he owned. Uncle Merle raised tomatoes, greens, and other staples, while his wife, Norma, canned various fruits and jellies. “His garden was so big and beautiful, it’s like you could take it out of a magazine and put it in his yard,” Earl Stripling recalled.

Whether Earl Stripling was helping out at his uncle’s garden on the northern edge of Greenwood or visiting his grandmother’s massive football-field-sized farm out in Okmulgee, he was picking up valuable lessons about agriculture he would carry for the rest of his life. “I will grow only what I eat,” he said. “It would be a waste if you grew something, and you done nurtured this thing for months on end and you don’t even eat it.”

Billie Parker also learned how to tend the land from a grandmother in Okmulgee with a garden that seemed impossibly large in the eyes of a little girl. “When I was little, she would say, ‘Girl go out there and get tomatoes or cucumber’ or something like that…that’s really where I started from,” Parker said. “I’ve been farming all my life.”

At the Community Pride Farmer’s Market, Parker rents out small 4-by-1-foot plots of land to families for a season and offers them help raise easy-to-cultivate crops like tomatoes and radishes. She also runs the Black Wall Street Market, a store and history center on the same property and hosts a dashiki festival every other week during the summer. She’s currently working on building out a workspace where children will be able to learn other valuable homemaking skills such as cooking, sewing, and ceramics. “Our future is our children,” she said. “When they come out of here, they might plant something, a little seed to take back with them…they really love it.”

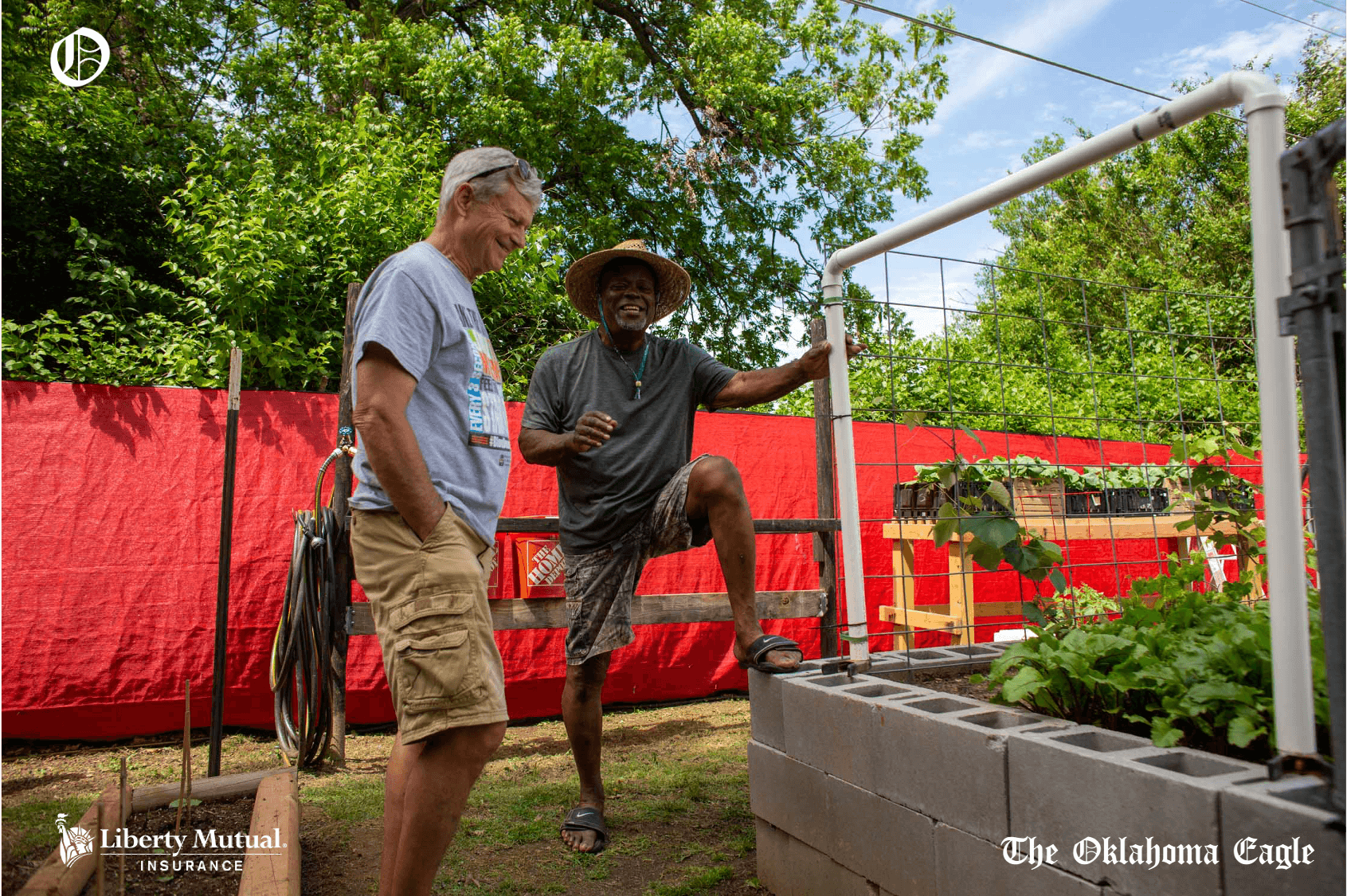

Stripling, meanwhile, is working with former Tulsa police officer Dean Finley to build a community garden on a one-acre lot on 31st Street North, across the street from the North Mabee Boys & Girls Club community center. The new space will feature gardening classes, cooking instruction, and a produce store. Their hope is that the kids who play at North Mabee will be some who benefit the most. Stripling will be teaching the gardening lessons himself. This spring, he began developing a similar community garden with Vernon AME church, located right in the heart of Greenwood. “A lot of people want to grow, they just don’t know how,” he says. “I’m going to teach them how to grow and sustain themselves.”

Both Parker and Stripling’s initiatives are motivated in part by the fact that much of North Tulsa is a food desert, with few grocery stores and nutritious foods available in the area. Parker bought her farm after the Gateway Market near Pine Street and Peoria Avenue closed in 2017. “I said, ‘Wow, we need to grow our own food,”’ she recalled. And she found support from her neighbors. It was people from the surrounding neighborhood who helped her erect the massive hoop house.

The coronavirus pandemic has also made the importance of self-reliance more clear in the eyes of many North Tulsa residents. At the onset of the pandemic in March 2020, lines to enter grocery stores stretched for blocks, many items were often sold out, and food supply chains were disrupted. “With this pandemic going on, I think people need to learn how to grow, because you never know what these department stores are gonna do,” Stripling said. “You can go in there, and the shelves will be empty. They will be bare.”

Though Stripling’s first career was as a machinery operator at a milk plant in town, he rekindled his passion for gardening about a decade ago. He began by growing tomatoes, his favorite crop, out of a small five-gallon bucket. Now he posts his sprawling, green bounty regularly on Facebook. He also fields questions from hundreds of would-be farmers every day. He imparts them with wisdom about the best vegetables to start with for a beginner or the appropriate potassium-nitrogen-phosphorus balance for onions compared to turnip greens. Though he could sell what he grows at farmer’s markets, for now he is content to share his food — and his knowledge — for free.

“”Not only Black people, I think everybody should learn how to do this,” he says. “It feels so good to get hungry, and then you can walk out your back door and say, ‘I’ve got my pick of the litter.’”

Victor Luckerson is a journalist in Tulsa who is writing a book about the city’s Greenwood district, and an online newsletter about neglected Black history called Run it Back.”