By Taryn Finley

The Greenwood district is a crime scene. There’s no yellow tape or investigative markers in sight, nor are any law enforcement officials in pursuit of justice. But signs of a fatal crime — disregarded dead bodies, bricks curled upward after being set ablaze and a psychological trauma that reverberates around the city — stick to the air.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the 18-hour attack known as the 1921 Tulsa race massacre, one of America’s deadliest acts of domestic terrorism. At least 300 people died during the events from May 31 to June 1, 1921, according to historians. Black residents sought refuge in the homes they had built, even as those homes were looted and burned. Churches were bombed. Pregnant women were brutalized. Children were murdered. An entire thriving community, at least 35 square city blocks, fell.

No one was persecuted in the aftermath. The massacre’s impact on the city and its residents was diminished, and the events were branded as a “race riot.” What should be considered one of America’s most historic efforts to thwart Black progression after enslavement barely gets a mention in U.S. textbooks. If it isn’t amnesia, it’s apathy. And if neither, it is a tragically quintessential American story of how white terror seeks to destroy communities of color and tell a revisionist history.

The city formed the Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission to prepare for the anniversary and educate the masses in 2016, an effort to put the spotlight on Greenwood and honor victims. News outlets and TV networks have also brought national attention to the massacre in recent years.

But as the same city that played a role in the destruction of Greenwood — an area known as Black Wall Street because of its prosperous, self-sufficient economy — tries to find a path toward reconciliation, survivors and descendants are still fighting a century-old battle for justice and accountability. As the centennial approaches, Black Wall Street will become home to events featuring celebrities and politicians and millions of dollars in funding toward tourist attractions. Yet the last remaining survivors don’t have a say in any of it. They don’t have control over how their stories will be told, and they won’t see any profit.

There are three known remaining survivors of the 1921 massacre: Lessie Benningfield-Randle, 106; Viola Fletcher, 107; and Hughes Van Ellis, 100. They’re all fighting for reparations from the city of Tulsa. Randle, known as “Mother Randle,” filed a complaint on Sept. 1, 2020, that “seeks to remedy the ongoing nuisance” caused by the massacre and “obtain benefits unjustly received by defendants.” It also names residents of the Greenwood community and members of the predominantly Black area of North Tulsa as “victims of this nuisance.” City officials misused funds intended to help victims of Greenwood and implemented policies that led to further economic and health disparities in Black Tulsans, according to the suit.

On May 19, the three survivors traveled to Washington, D.C., to testify about their experiences before a House subcommittee on civil rights and civil liberties. It was the first time they had shared their own stories on a national stage.

“I will never forget the violence of the white mob when we left our home,” Fletcher told lawmakers. “I still see Black men being shot, Black bodies lying in the street. I still smell smoke and see fire. I still see Black businesses being burned. I still hear airplanes flying overhead. I hear the screams. Our country may forget this history, but I cannot. I will not. And other survivors will not. And our descendants do not.”

Fletcher, known as “Mother Fletcher,” described how the massacre affected the rest of her life. She was forced to leave Tulsa and never got an education beyond the fourth grade. She testified that she never made much money, despite supporting the United States’ war efforts working in California shipyards. She still lives in poverty, barely being able to afford her everyday needs.

“We lost everything that day. Our homes, churches, our newspapers, our theaters, our lives. Greenwood represented the best of what was possible for Black people in America and for all the people,” she said. “No one cared about us for 100 years. We and our history have been forgotten, washed away.”

She said she’s praying she’ll see justice.

Damario Solomon-Simmons, the attorney representing the survivors and founder of Justice for Greenwood Foundation, the nonprofit working toward reparations for survivors and descendants, told HuffPost that Tulsa’s effort to commemorate the centennial has been “a whitewashing” and that the city should be making cash payments to those affected. Instead, the city is building Greenwood Rising, a $30 million museum survivors and their descendants say benefits Tulsa more than them.

“This was just a shell game for the city and the state and the chamber of commerce to look good, to try to act like they were trying to do something for the Black community, because they thought all of the opposition to their activities was done and dead,” Solomon-Simmons said. “They had no idea that we still had survivors and descendants who still wanted reparations and justice. They thought they could just do what they want, prioritize white Tulsans and white business owners and create a scenario where they can look into the world and have the world look at us, look how great we are, and make all this money off the massacre.”

J. Kavin Ross, a descendant of survivors who aren’t specifically named in the lawsuit, described the centennial events as the city “pimping our history.” Ross’ great-grandfather owned the Zulu Lounge before it was destroyed in the massacre. Today, Interstate 244 sits on that lot — all Ross’ family has is a plaque in the ground that the city doesn’t even help maintain, according to Ross and other community members. He dreams of reopening a version of Zulu Lounge one day, but all he has now is “a highway sitting on my inheritance.”

He said grand gestures from the city like Greenwood Rising aren’t comparable to justice. And the museum and events taking place around the centennial are just crumbs in comparison to what Greenwood and North Tulsa are owed.

“I can only go back on what my great-grandmother used to tell us: ‘I don’t care how much syrup that you pour on mud, you can’t call it pancakes,’” Ross said. “What she meant by that? Who y’all think y’all fooling?”

The Miseducation of the Tulsa Massacre

The story of Greenwood traces back to the early 20th century. Many Black folks who ended up in Oklahoma were enslaved by Indigeous people and walked the Trail of Tears with their enslavers. After the Civil War, Black folks began to voluntarily travel north and west to begin new lives. This led to the creation of several all-Black townsin Indigenous territories from 1865 to 1920. In these communities, Black folks sought protection, economic gain and promising futures for their families.

Ottawa W. Gurley, a self-taught son of enslaved parents, saw that vision when he moved from Arkansas to Perry, Oklahoma, in the late 19th century. Perry was one of the towns advertised to Black migrants — Gurley envisioned Oklahoma as a refuge for Black settlers after emancipation, imagined a future where Oklahoma could become a Black state.

By 1905, he had moved to Tulsa, a city founded by Ku Klux Klan member W. Tate Brady, and bought 40 acres of land so Black folks could build on it. Gurley believed Tulsa was ripe for opportunity, as the oil boom had just begun. He named the area Greenwood after a town in Mississippi. He mapped out the area to be divided into commercial and residential lots, adding a grocery store, hotels and other businesses.

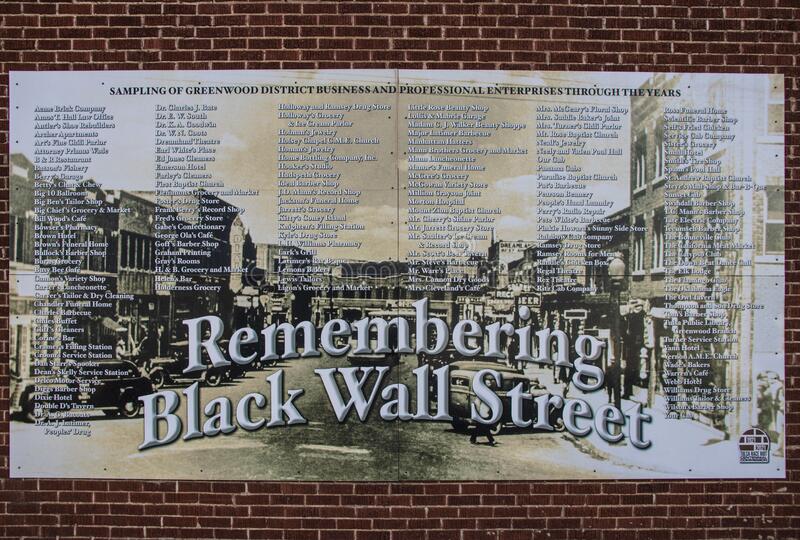

Greenwood became home to churches, schools and community organizations and an estimated 200 Black-owned businesses by 1921. It sat — and still sits — north of Tulsa’s Frisco rail tracks, which separated the northern, Black side of town from the southern, white side. J.B. Stradford, Gurley’s business partner, famously opened the Stradford Hotel; he also owned about two dozen rental houses, pool halls, shoeshine parlors and bathhouses. John and Loula Williams owned a confectionery, as well as one of Greenwood’s crown jewels, the Williams Dreamland Theatre. A.J. Smitherman founded the Tulsa Star, one of two Black newspapers in the city at the time, and empowered Black people to diversify their votes when most were voting primarily for Republicans. Simon Berry built a private transportation network that carried residents through Greenwood to downtown Tulsa, and he chartered planes for wealthy oilmen.

Greenwood, formed out of necessity during segregation, became a prosperous community. Sharecroppers and others moved to Greenwood, a dreamland for Black progression. Doctors, lawyers, pilots, shoe shiners, barbers, grocers, realtors, educators and so many other professionals flourished. All but a few businesses in Greenwood were Black-owned. Educator and author Booker T. Washington dubbed Greenwood “Negro Wall Street.” Later on, it would also be called “Little Africa.”

“I have never seen a colored community so highly organized as that of Tulsa,” scholar W.E.B. Du Bois told the Daily Oklahoman. “The colored people of Tulsa have accumulated property, have established stores and business organizations and have made money in oil.”

On May 30, 1921, a white woman’s scream triggered the violence that led to Greenwood’s burning. That afternoon, Dick Rowland, a Black shoe shiner known as “Diamond Dick,” attempted to ride an elevator at the Drexel Building on South Main Street with Sarah Page, a white elevator operator. Folks nearby said they heard Page scream, though little is known about what actually happened. Rowland ran as the police were called. The following morning, the Tulsa Tribune published a story with the headline “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in an Elevator.”

The article said police had arrested Rowland and charged him with assault, though it was later reported that Page never told police that he had harmed her. The Tribune claimed that she said he had attacked her by “scratching her hands and face and tearing her clothes.” The article, like others shared by white-owned papers of the era, leaned on racial stereotypes to evoke fear of Black people. And it worked.

White mobs arrived at the courthouse where Rowland was being charged in hopes of lynching him. Black Tulsans also came to the courthouse to help protect Rowland. Police declined their assistance. Fights broke out. Shots were fired. The Black Tulsans headed back to Greenwood, and the white mob followed. Families got word that white folks were going to be coming to Greenwood and began leaving town before they arrived.

The massacre began on the evening of May 31. A white mob, including some people in Blackface, stormed Greenwood carrying weapons. Klansmen, deputized individuals and other racist white Tulsans attacked, looted and burned down homes and businesses, many of which had people inside.

Many community leaders were targeted. Smitherman, the newspaper editor, was among them. Klansmen set his home ablaze. His family hid in the basement and escaped when the KKK moved on to further destroy the community.

Raven Majia Williams, Smitherman’s great-granddaughter, told HuffPost that her great-grandfather and his family left town that night and never returned out of fear that they’d be lynched.

“I wouldn’t be here if they didn’t get out,” said Williams, who’s based in Los Angeles. “And I’ve heard firsthand tales of my great-aunt and my great-uncle who were survivors, and told me flat out what happened. And my Great-Aunt Carol, who was like a grandmother to me, she would always tease my dad and say, ‘If it wasn’t for me, you wouldn’t be here, because I carried your mama out of that basement.’”

The people of Greenwood were outnumbered, but they put up a hell of a fight. They defended their families, homes and businesses as much as they could against gunfire and bombs. They stood their ground until the next day, when their beloved community was bombed by planes, as reported by witnesses, according to the 1997 Oklahoma Commission on the massacre. It’s the first known domestic airstrike to take place in the U.S., according to historians.

The death toll was initially reported to be 35. However, after bodies were found dumped in mass graves around Tulsa, historians believe the number to be closer to 300. Thousands of residents were displaced and many traveled north, a reason why North Tulsa is mostly Black today. The mob took many at gunpoint and forced them to stay at concentration camps, only to be “released” if they agreed to involuntary servitude. One camp was located at Brady Theater, now named Tulsa Theater, and another was at McNulty Park, which is now a Home Depot.

“They had to walk there with their hands up, and if your hands came down, you were shot at, if not shot,” said Rev. Robert Turner, head pastor at Vernon A.M.E. Church. “There was the story of this woman who was pregnant, couldn’t walk fast enough. The white mob comes to her, cuts her belly open, takes the baby out of her stomach, throws the baby to the ground, takes their boot, thumps baby’s head in and tells the mother to get back in line and keep walking. Blatant disregard for life, and this is in a so-called Bible belt where they believe in the rights of the unborn.”

In the aftermath, the Red Cross provided aid. They never distributed funds and resources meant for the survivors. People around the country donated money and supplies for relief, but the city government in Tulsa, however, barred reporters from telling the story and assured outsiders that they had the situation handled.

City officials did everything they could to cover up an attack they had been complicit in, which included hiding the front-page story that was the catalyst for the massacre. (The front page for the May 31, 1921, edition of the paper had been missing from archives until historian Beryl Ford found the original article in 2002, Tulsa World reported.) So began a culture of silence.

Historian Kimberly Ellis, an author and speaker who hosts discussions about the Tulsa race massacre across the country, told HuffPost that city officials were either too embarrassed or racist to allow the real story of the attack to get out. Still, postcards displaying dead Black bodies, burning buildings and the destruction of Negro Wall Street circulated.

Survivors were either too fearful of white retaliation to talk about what happened or too traumatized. In many cases, both were true.

Very few victims received proper burials. Perpetrators buried bodies in mass graves and dumped them in the Arkansas River. Authorities didn’t start investigating claims of mass graves until 1998 — an effort that was discontinued shortly after — and again 20 years later under Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum. The Mass Graves Oversight Committee, established by the city in 2018, reported finding bodies in an area park and cemetery, as well as in nearby Rolling Oaks Memorial Gardens, which was formerly Booker T. Washington Cemetery. In March of this year, 12 bodies were found in a mass grave near the headstones of the only two known victims buried in the Oaklawn Cemetery’s Black section.

“Some of us handle trauma by going to fight for their rights and they’ve all been denied. The vast majority have just suffered in silence, painted over it, transformed it to something else to keep from talking about it. The people who I’m really fighting for are not even here anymore, but their legacy, their fight, the denial of them receiving justice, is why I do what I do.”

Rev. Robert Turner

This was the worst documented race massacre in American history, and so much about it is still unknown. Many Americans have no idea it even happened. Many Tulsans, regardless of race, didn’t learn about it until adulthood — it will be a required part of Oklahoma’s state curriculum for the first time this fall. Accompanying lessons about critical race theory will be banned, however: Just weeks before the 100th anniversary of the massacre, Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt (R) signed a bill prohibiting critical race theory from being taught in classrooms. As a result, he was removed from the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission.

Ellis said the white terrorism that destroyed Tulsa in 1921 is an ancestor of the white terror that exists in today’s America. The white animosity that grew toward Black economic and political advancement after the Civil War is akin to the brand of white supremacy that arose before, during and after President Barack Obama’s election. This animosity led to a rise in hate crimes, and emboldened Donald Trump — who won all 77 counties of Oklahoma in the 2016 and 2020 elections — to considerholding one of his first campaign events of his 2020 reelection run on Juneteenth. And it led to thousands of insurrectionists storming the Capitol, unchecked and unhinged.

Black progression in Greenwood infuriated white Tulsans, Ellis said.

“White America, you need to decide what type of country you want to live in,” she said, “because these white supremacists, they’re never going to stop till you stop them.”

The Fight For Reparations

“There is no statute of limitations on morality,” Turner, the pastor, declared through a bullhorn as he held a picket sign that read “Reparations Now.” “There is no expiration date on morality, and wickedness does not does not disappear over time. In fact, wickedness becomes like spoiled milk. It gets worse overtime. And Tulsa, you stink like spoiled milk.”

On April 28, a month before the centennial, the sky shed gentle tears as Turner gave his impassioned weekly sermon, not from his pulpit but from outside of city hall. Employees walked out of the building, briskly passing the protest — some wearing ear buds, all making sure they didn’t acknowledge the nine demonstrators.

Whether he’s joined by many or he’s by himself, Turner has made a point to rally for reparations each Wednesday since Sept. 12, 2018. And despite being attacked during a protest in 2020, he continues to risk the danger. He doesn’t have a script when he’s out there.

Turner, originally from Tuskegee, Alabama, has been in Tulsa for five years. He relocated there to become the 22nd head pastor of Vernon A.M.E. Church. The basement of the church is the only structure still standing from before the 1921 massacre. When the violence ended and folks returned to what was left of Greenwood, congregants and others began rebuilding the church brick by brick.

Construction workers renovating the basement knocked down walls and smelled the scent of smoke from 1921. Most chillingly, the room where survivors hid in the basement as the church burned remains, a thick, double brick wall in front of sheet rock protecting it. It’s cold down there, but far from lifeless.

Turner considers the basement one of the most historic places in all of the U.S. Yet, to this day, it serves as a janitors’ closet — symbolic of how much the story of the massacre has been buried. Turner said he’s working to reverse that.

“Some of us handle trauma by going to fight for their rights and they’ve all been denied. The vast majority have just suffered in silence, painted over it, transformed it to something else to keep from talking about it,” he said. “The people who I’m really fighting for are not even here anymore, but their legacy, their fight, the denial of them receiving justice, is why I do what I do.”

The 116-year-old building is the oldest piece of property continuously owned by Black people in America, according to Turner. It’s intact, but he said it needs $1.2 million worth of repairs. A couple of grants in recent years have helped fund some structural updates and restore stained-glass windows in the sanctuary. The church recently got approved for historic landmark status, but Turner said it’s clear that preserving its history is not as big of a priority as preserving some racist landmarks and institutions in Tulsa. Although some landmarks and schools, including Brady Theater and Robert E. Lee Elementary, have been taken down or renamed, others, including the Tulsa Association of Pioneers Monument that honors KKK members, have not.

“I think that some people care,” Turner said. “But right now the people in power, I’m not saying they don’t care, but they apparently care more about retaining power than they do about dispensing justice. How can you know about this and you say you care, but you don’t do anything about it?”

Oklahoma waited nearly 80 years after the massacre to face it.

In 1997, the state passed House Joint Resolution No. 1035, which formed a commission to study the 1921 massacre and give recommendations for reconciliation. That commission, led by Bob L. Blackburn, the executive director of the Oklahoma Historical Society, published a 200-page report ahead of the massacre’s 80th anniversary in February 2001. The commission conducted interviews with hundreds of survivors, many of whom publicly broke their silence about their experiences.

The massacre was “an evil from which neither whites nor Blacks have fully recovered,” the commission said. In the prologue of the report, State Rep. Don Ross, J. Kavin Ross’ father, wrote about the negligence the local government showed Greenwood in the aftermath of the attacks.

“There was murder, false imprisonment, forced labor, a cover-up, and local precedence for restitution,” the report states. “While the official damage was estimated at $1.5 million, the black community filed more than $4 million in claims. All were denied. However, the city commission did approved two claims exceeding $5,000 ‘for guns and ammunition taken during the racial disturbance of June 1.’”

The destruction amounted to more than $200 million in today’s money.

Some residents of Greenwood rebuilt their homes and businesses from ash and rubble, bringing back a thriving community without the help of the city or state. Insurance companies wouldn’t honor their claims, and many local white-owned businesses refused to offer materials and supplies to aid in reconstruction. Black residents rebuilt with whatever bricks and materials they could access, sometimes bringing them from out of town.

But Greenwood never returned to its original state. It started to become economically prosperous again in the 1930s and 1940s, but as it climbed, so did racist policies and KKK presence. New federal redlining laws made it nearly impossible for Black people to get approved for mortgage loans for homeownership. (This continues to be a hurdle, as Black Tulsans’ home mortgage applications were 2.4 times more likely to be denied than white applicants as of 2015 and 2016, despite anti-discriminatory legislation.)

Redlining led to a steady divestment in Greenwood. Black folks began spending more money in white communities when Tulsa began integrating in the 1950s, but white Tulsans didn’t patronize Black-owned businesses in nearly the same way.

Urban renewal, called “urban removal” by many Black Tulsans, led to further decline; more than 1,000 homes and businesses, many of them in Greenwood, were demolished. This pushed even more Black folks north. Other residents were forced out as Interstate 244, which severs what’s left of Greenwood, was constructed in the 1960s.

There was no relief for Greenwood in the decades following the massacre. Instead, there were mounting obstacles placed on Black Tulsans. The 2001 report laid out a list of recommendations for the state: give direct cash payments to survivors, give payments to descendants, create a scholarship fund for students impacted by the massacre, establish an economic development enterprise zone in Greenwood and create a memorial for the reburial of any human remains found in the search for unmarked graves victims.

But the state refused to act. Attorney Charles Ogletree filed a lawsuit against the Oklahoma governor and Tulsa police chief in federal court on behalf of more than 400 plaintiffs, including 125 survivors, in 2003. Johnny Cochran, Randall Robinson and Adjoa Aiydtoro were also on the legal team. Lower courts denied the claim, arguing that the statute of limitations had expired. In 2004, a federal appeals court voted against a rehearing, and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case a year later.

Enter Solomon-Simmons, who was a new lawyer when Ogletree worked on the first case. He said he’s taken the lessons he learned from watching that case unfold to represent the last remaining survivors.

“Justice will require that there’s financial compensation paid for those who suffered the harm and the continuation of the harm, that there is actual accountability for those entities that are still here that perpetrated the harm,” he said. “An opportunity to tell our own stories in our own way, an opportunity to be properly compensated for our stories. Like right now, they want to use our stories for free to line the pocketbooks of themselves. None of that is just.”

Solomon-Simmons said a big push for reparations started when certain survivors’ and descendants’ voices were excluded from the 1921 Tulsa Massacre Centennial Commission. The attorney shared an email sent to commission chair Kevin Matthews on behalf of Tedra Williams and Melanie McClain, descendants of Wess H. Young, the late survivor and community activist. They asked to be invited to a meeting regarding centennial plans in 2016. Matthews, who was also a state senator, replied that the meeting wasn’t “an open committee to the public.”

“All members are elected, or public officials, or have ties to private funding to make this 5 year initiative happen,” Matthews wrote in the email, which HuffPost has reviewed. He noted that survivors and descendants would be able to join a committee “once the current commission finalizes all funding mechanisms and national designations required for long-term tourism and historic benefit.” Select descendants were included in the planning, but Solomon-Simmons said none of the survivors were included.

Matthews did not respond to a request for comment.

Solomon-Simmons said declining to allow Williams and McClain to participate continued a nearly century-long systemic problem of excluding survivors and descendants from telling their stories. He said the current commission can’t be separated from the state, and that the state is profiting off of the pain of survivors and their descendants.

“This was a money grab and a whitewash. This was never about the people,” he said. “Greenwood was not about a place. It was not about buildings. It was not about anything but the people who founded it, who fought for it, who built it up, who defended it, and who lived there. The people is what should be first, and they put the institutions and the white community and white Tulsa and not the Black people who suffered.”

Phil Armstrong, project director for the centennial commission and an Ohio native who’s been in Tulsa for 26 years, said he supports reparations in Tulsa. But his approach is different from that of Solomon-Simmons and Turner, he said. He’s hoping that incremental changes and educating folks with political power will lead to future reparations.

“We had to sit here and take the route of, ‘which will bring worldwide awareness to this and will have greater impact on the other?’” Armstrong said in an interview in late April. “If we focus strictly on reparations, we wouldn’t be here right now with the world watching. That is a hard conversation to have, and we’re in Oklahoma, a conservative state.”

His goal isn’t to “satisfy everybody,” but to educate people about the massacre. He told HuffPost that that is his way of working toward reparations, and that he believes educating people who never learned about the Black Wall Street will lead to a greater understanding of what reconciliation looks like. He said he’s hopeful that individuals in the community will open their purses for the remaining survivors before the government will — but that shouldn’t be confused with reparations.

Armstrong said the community needs restitution in the form of money, community investment, educational initiatives and economic empowerment zones, as the first commission suggested. “All of that falls under reparations,” he said. “It’s much more than just writing a check.”

However, he acknowledged that the remaining survivors probably will not see reparations in their lifetime. After all, Bynum, Tulsa’s mayor, has come out against the idea, saying in February 2020 that he wasn’t focused on cash payments to survivors or descendants and that reparations would be divisive. Bynum declined to comment to HuffPost on reparations, citing pending litigation and the centennial commemoration.

And It’s been difficult for the commission to get community buy-in. The group has faced a few controversies, including the governor’s recent removal and calls for Sen. James Lankford (R-Okla.) to be ousted after he questioned the validity of the 2020 election.

Ellis told HuffPost that when she worked on the lawsuit with Ogletree in the early 2000s, the loss of generational wealth stuck out vividly.

“Some of them could not afford to pay their phone bill. I thought that was criminal, because had they been left alone or had they received their reparations, they would not have been in that situation,” she said. “This is a seminal case, and this is shameful that we are still working on a case for reparations for Tulsa. Because if anybody deserves reparations, it is the Black Tulsa community.”

Solomon-Simmons said survivors and descendants have waited long enough for restitution, and he is fighting to help them get that sooner than later.

Solomon-Simmons sent Armstrong a cease-and-desist letter last month, calling for the commission to stop using Randle’s “name or likeness in the promotion of” Greenwood Rising or other commission activities. The letter states:

“If the Commission were genuine in its words regarding Mother Randle, it would be revealed through tangible actions supporting her, which are notably missing. For example, the Commission did not allow Mother Randle (or the other two known survivors), any input regarding the formation, membership, and/or goals of the Commission. To-date the Commission has never invited Mother Randle to any Commission meetings or events. To-date the Commission has not discussed with Mother Randle how she feels about the Commission pushing narratives that ‘Greenwood is Rising,’ ‘Tulsa Triumphs,’ or that ‘Tulsa is leading America’s journey to racial healing,’ while she still lives in poverty because of the Massacre and its continued harm.”

The Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission is calling for reconciliation, but Solomon-Simmons said financial compensation is required for “those who suffered the harm and the continuation of the harm.” That “continuation of the harm” can be seen in the systemic injustices that led to the 2016 police shooting of Terence Crutcher and the acquittal of former Tulsa police officer Betty Shelby. (Solomon-Simmons worked on Crutcher’s family’s case.)

He said justice also requires accountability for institutions that are still “perpetuat[ing] the harm.” He’s demanding the return of stolen property, a scholarship fund and acknowledgment from the city, state and chamber that they’re responsible for the massacre..

“Greenwood was not about a place. It was not about buildings. It was not about anything but the people who founded it, who fought for it, who built it up, who defended it, and who lived there.”

Damario Solomon-Simmons.

“Those are just a few of the things that will start us towards a journey of healing. An opportunity to tell our own stories in our own way, an opportunity to be properly compensated for our stories,” he said. “Right now, they want to use our stories for free to line the pocketbooks of themselves. None of that is just.”

In 1997, state Rep. Don Ross, who raised more than $3 million in money from private donors to fund the Greenwood Cultural Center and wrote the bill that led to the first commission, apologized on behalf of the state, saying that no one has ever done so. Former Oklahoma Gov. Frank Keating (R) and former Tulsa Mayor Susan Savage also made apologies at events related to the massacre that year, Tulsa World reported. In 2013, Tulsa Police Chief Chuck Jordan apologized that the department “did not protect its citizens during those tragic days in 1921.”

But Ellis said offering an apology without reparations isn’t acceptable. The significance of this case can’t be understated.

“It will be probably the most important case for reparations because it includes the Native American, the Creek freedmen, and it includes the freedman story,” she said. “So, it means that it includes Native American slaveholders, and freedmen, it includes African Americans who were called state Negroes, and it includes the arrival of the state of Oklahoma and the arrival of white supremacy and Jim Crow segregation. It is the most American tale ever.”

Several descendants and Black Tulsans interviewed for this story said they experience post-traumatic stress syndrome linked to both the massacre and institutional racism in Oklahoma. Willams, who has been trying to tell her family’s story but has been rejected by several Hollywood executives, said people in her community have inherited both trauma and resilience.

“We inherited the resilience that it took for the first free generation. My great-grandfather was part of that first free generation, to build a Black Wall Street, to overcome,” she said. “But for me, I don’t want to keep having to overcome. Because 100 years later, why are we still having to fight for the same things?”

A Community Healing Itself

A haunting history, coupled with decades of gentrification, continue to physically constrict Greenwood, but the spirit of entrepreneurship and forward movement is alive among its business owners. Younger generations have picked up the torch carried by victims, survivors and those who fought for and rebuilt Greenwood. Where hope was meant to be lost, they’ve sustained it.

A playlist featuring Kehlani, DVSN and Summer Walker played in the background as Kode Ransom, Angel Jamison and Raynell Joseph discussed the state of Black Tulsa late last month, something not uncommon at Black Liquid Coffee Lounge on Greenwood Avenue. They discussed the self-actualization of Black Wall Street’s founders and how it fuels them now.

The conversation wasn’t all serious, however. They weaved in and out of the heavy stuff with playful jabs at each other. It’s all love. They were surrounded by art that speaks to the entrepreneurial history of Black Wall Street, the creative legacy of musicians like the G.A.P. Band, and the simple, yet crucial reminder to choose joy as a form of self-care.

Guy Troupe and Dwight Eaton started Black Liquid Lounge in January 2020, but decided to take a step back and let Ransom and Jamison run the show. Ransom, a poet and rapper, helps run the coffee shop, while Jamison, an artist and recent college graduate, serves as barista.

Ransom is a neighborhood historian. He holds free tours for visitors, with the request that they spend their money supporting a Black business in Greenwood. His 45-minute tours start at a mural, painted by Jamison, that shows Greenwood’s prominent historical figures. He wants people to get a full understanding of Greenwood and how its fall — both in 1921 and after urban renewal — led to the inability for Black folks to outright own their businesses on Black Wall Street today.

“Gentrification at its extremes. It’s like an anaconda effect. It slowly chokes you out, and boom. A block is all we had.”

Cleo Harris

“The city was founded by a Klansman. He said he’d never allow Little Africa to be rebuilt and even when they rebuilt it, and here comes the highway to take down again so it’s the fact that he said that and to this day the city stuck to that,” Ransom said. “So no matter what, when you look around and you see the building going up, not only is it not Black people doing it, it ain’t even Black contractors building it. Now we can rent on Black Wall Street, if you’re trying to actually own here, ain’t nothing for you.”

Armstrong and others argue that what’s happening in Greenwood is a result of Black people selling or not investing in the buildings they owned in the area, not gentrification.

Ransom told HuffPost that gentrification is indeed at play, and that it’s further evidence that the city refuses to fully reckon with its past. As he has watched all but one block of Greenwood turn into modern mixed-use developments, he has also witnessed the preservation of Brady Heights, a neighborhood named after the KKK member who founded Tulsa and given historical significance because the architect is ”more sophisticated″ than others.

“I would say that if they are not intentionally being disrespectful, they definitely are doing it by accident,” he said.

Cleo Harris, owner of Black Wall Street Tees and Souvenirs — one of the less than two dozen Black-operated stores in Greenwood today — told HuffPost that many of the plaques on the sidewalk meant to pay tribute to the businesses destroyed in 1921 have been removed or destroyed with the construction of the Tulsa Drillers’ baseball stadium, erection of a Holiday Inn and continued work on the highway overpass on Black Wall Street. The Tulsa native watches from his shop as people ride scooters over the plaques, ignore the ashes still visible on bricks and regard the area as anything other than “sacred ground.”

A few doors down from his shop is a health clinic owned by a white woman with a big banner that reads “Trump 2020.” A few doors down from that is Fat Guys Burger Bar, a restaurant catering to the baseball field east of Greenwood. In a few years, a BMX track will sit on the west side of the now shrunken Black Wall Street.

“Gentrification at its extremes. It’s like an anaconda effect. It slowly chokes you out, and boom. A block is all we had,” he said. “We have been so gentrified, whitewashed of our history that they didn’t want to remember this. Even our elders didn’t want to remember this, because they were afraid that they were going to start another race war.”

Harris is mad as hell. But that won’t stop him from running his business in the spirit of Greenwood. He makes shirts for Frios Gourmet Pops, L Loc Shop, Liquid Lounge and other Black businesses and organizations. Harris also makes a point to spend his money in Greenwood often.

“The lady straight across the street, the Tax Solutions, S. LaToya Rose, she’s my bookkeeper,” he said. “And then there’s a store coming in, I’m doing aprons, and I was able to invest in her to help her, to get her store started. And they of course Wanda J’s. Upstairs is a lady by the name of Emily Harris. She does life insurance. Me and my family have life insurance so my money goes upstairs, right above me.”

As he handpresses T-shirts with graphics and messages that commemorate Black Wall Street and denounce racism, he thinks about the chilling experience he had at age 10, when a survivor told him and his friends about the gruesome deaths he witnessed. “He said, ‘Never forget, young blood,’” Harris recalled as his eyes watered a bit.

Though it may not be as overt as it used to be, institutional racism is alive and well in Tulsa, and has a great impact on the livelihoods and life expectancies of Black residents. Despite the odds being against them, however, younger generations are not waiting for the government or any other entity to empower their community. They’ve picked up the torch that those who came before them and built up Greenwood carried.

Descendant Nehemiah Frank, for example, was a school teacher and principal at Sankofa Elementary School. He taught his third-grade class about the drive of Greenwood’s founders and urged them to reach for excellence before leaving to work on his news publication, The Black Wall Street Times. Frank is walking in the footsteps of Smitherman by telling stories about Black Wall Street that white-owned local outlets can’t and won’t.

Venita Cooper, a transplant born in New Jersey and raised in California and Mississippi, opened Silhouette in November 2019. The shoe store sits on the same lot as Grier-Shoemaker, a Black-owned shop destroyed in the 1921 massacre. She has used the space to make streetwear and as a place where local artists can showcase their work.

Onikah Asamoa-Caesar, born in New Jersey and raised in California, moved to Tulsa in 2013 for Teach for America. That’s when she learned about the 1921 massacre, despite majoring in history in college. She told HuffPost that she felt the racial tension as soon as she moved, getting stares as one of the few Black women in white-centered places.

She noticed Tulsa was a city “growing without us in mind.” It got to the point where she left Tulsa for a bit but came back because she felt like she was “abandoning history” when she could be building upon it. She opened Fulton Street Books in October 2020, about five minutes away in Grady Heights. Asamoa-Caesar’s bookstore and coffee shop provides a space for Tulsans of color to meet and peruse books where they can see themselves reflected.

“I love being a bookstore owner, but there’s also this added responsibility of carrying on a legacy that was wiped out,” she said. ”There’s pride and resentment in that. Because I’m pretty sure Black Wall Street, in the early days, those owners just saw themselves as needing to provide their service for their community.”

Growth isn’t just happening among Black business owners downtown. Fifteen minutes away from Greenwood in North Tulsa, an economically starved area where 35.7% of the population is Black, the Gibbs, descendants of survivor Ernestine Gibbs, are working to make their shopping center a cultural hub once again. LeRoy Gibbs remembers fondly how his grandfather used to look out for the community, picking up customers’ tabs when they couldn’t afford groceries.

His family lost the shopping center once his grandfather died and LeRoy’s father didn’t want the responsibility of managing it. A wedge formed within their family, but LeRoy’s wife, Tracy Gibbs, told him, “The Lord told me that we’re going to get the Gibbs Center back.”

He wasn’t convinced.

“At that particular point, my heart wasn’t as connected at that time like it used to be because of just everything that happened,” she said. “But she was persistent.”

Sure enough, the Gibbs got their building back after the previous owner ended up in legal trouble. Like LeRoy’s grandmother did for their first business, Tracy used her retirement money to secure the Gibbs Center once again in 2015.

“Our whole focus has been community-driven, like his grandparents. It’s been community-driven, community-focused,” Tracy told HuffPost. “Our heart is not just the shopping center and not just trying to come up regarding ourselves or our family, but our heart is really trying to make sure that we’re doing what’s going to be best for this community.”

Stores in the shopping center include boutiques, a T-shirt-making business and a mental wellness facility for marginalized people. The Gibbs are particular about which new tenants they take on, straying away from liquor stores or any business that doesn’t give back into the community.

Their six tenants are all Black, and several are new business owners. Deadrick Gillespie’s business, Stingray Graphics, has been in the Gibbs Center for five years. He balances working at Tulsa International Airport five days a week and at Stingray with his wife and business partner Tammie Gillespie on Fridays and Saturdays. He makes shirts for events like family reunions, graduations and funerals. Running his business in the shopping center where he grew up playing is life coming full circle for the first-time entrepreneur.

“When we were talking about it, I said, ‘Let’s go north. We’re going to go where my roots are. I don’t care about nowhere else,’” Gillespie told HuffPost. “The first three months we were here somebody broke in the shop, threw a rock through the window, stole all our equipment and everything. Everybody was like, ‘Move south. Move south.’ I said, ‘I will never move south. My heart is out here.’ I want to be able to provide a service to my people so they ain’t got to go south.”

Cawanna DeLouiser is also a first-time entrepreneur in the Gibbs Center. She opened Snaggz Boutique in late 2020. At 19, she said she stopped going to downtown, in Greenwood and surrounding areas, to shop after she had a vision that she owned her own business in the very plaza Snaggz occupies now. She has only been in business for six months, but she hopes to encourage other businesses to open in North Tulsa. She believes the community is growing and doesn’t want Black people left behind.

“I just think that people need to know how to get more connected in the community as far as what we can do, and how we can help each other, and not focus on the bad and focus more on the good,” she said. “I mean, I love being out North because I can help people. I was a teenage mother. So if I could try to prevent a kid from making the same mistakes, I’m going to tell them. I’m a counselor, I’m a therapist. I mean, I’m everything.”

The Gibbs Center may not be in Greenwood, but it evokes the spirit of the Black Wall Streets of the past. The Gibbs’ 12-year-old son, Tripp, has been watching his parents work and has dreams of starting his own video game development business when he’s older.

“It’s really cool to know that it was owned by my great-grandfather and great-grandmother,” Tripp said. “And also it was great knowing that my great-grandmother was a survivor of the Tulsa race massacre. And I feel like that’s just a really big thing in my life. And I’m really glad they’re doing this. I feel like they’re really helping the community.”

After the flashy centennial commemoration events have ended, the tourists make their way back home and the national news outlets leave, Tulsa will still have a troubled past — and present — that continues to suffocate its Black residents. It’s a luxury to disassociate from how May 31 to June 1, 1921, left a lasting impact. Many Black Tulsans can’t, as the legacy of the city’s racism sticks to their livelihoods.

This is the true haunting of Tulsa. Until the city and state choose to contend with its ghosts head on, its past will continue to dictate its future.