By Victor Luckerson

Special to The Eagle

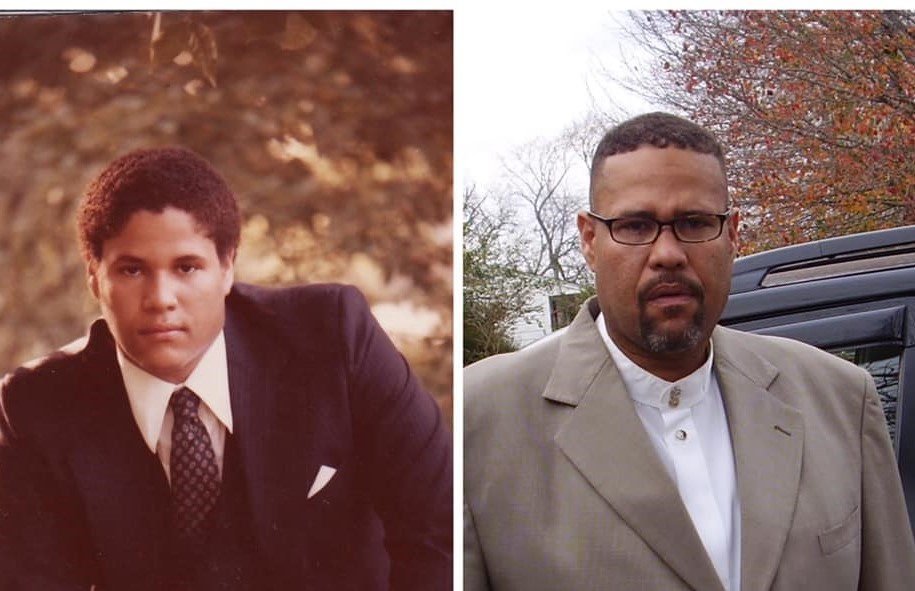

Leon Rollerson recalls the majesty of Juneteenth on Greenwood Avenue – the musicians performing on the backs of flatbed trucks, the sidewalks crowded with revelers, the dancing that spilled into the drug stores lining the street. “It was a celebration, sort of like a mini Mardi Gras,” says Rollereson, a prominent Tulsa musician and production company owner who came of age in the 1950’s. “People would be dancing all over.”

But the 75-year-old Rollerson also remembers Juneteenth as the one day of the year black Tulsans were allowed to visit Lakeview Amusement Park, which was located near the current Mohawk Park in North Tulsa. Every other day of the year, the merry-go-rounds carnival games were for white children only.

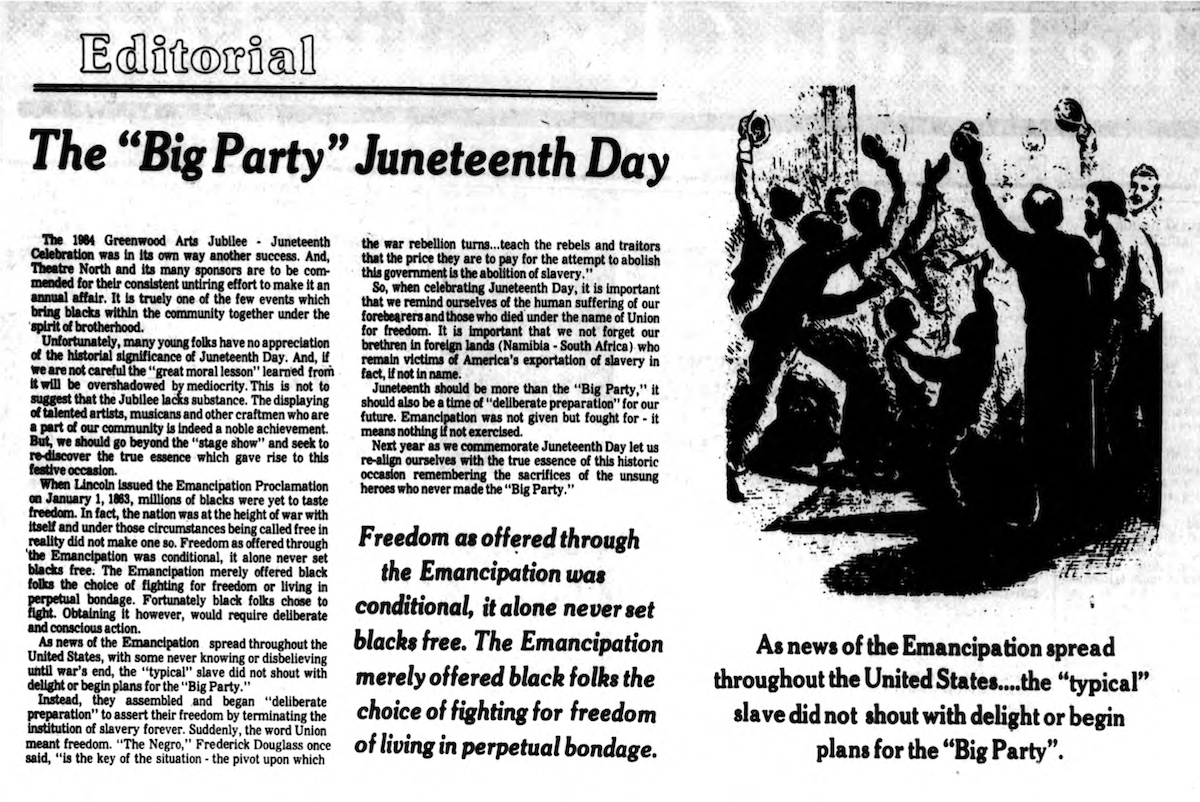

This is the dichotomy of Juneteenth. The holiday is a celebration of black people’s freedom from slavery, but it’s also a reminder that the struggle for true equality continues. When enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, were informed of their liberation by a Union general on June 19, 1865, the news came two months after the Confederate Army had surrendered in Appomattox, Va., and two and a half years after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Freedom came – and continues to come – late.

In Tulsa, perhaps because of its proximity to Texas and the self-reliant streak of its black community, the holiday has long been an important one. As far back as 1905 black Tulsans were celebrating some version of “Emancipation Day,” with a barbecue held at a city park that August. The celebration had shifted to the now universal Juneteenth date by 1913, when a man leapt from a hot air balloon and parachuted down to the crowd in Midway Park as part of the festivities.

The celebration grew in scale along with Tulsa’s black population. In 1950, Greenwood residents crowded into Lincoln Park on the northern edge of the neighborhood for a festival that included live music, barbecues, and rodeos. The three-day event featured speeches by local preachers, and prominent black state leaders, culminating in a spectacular fireworks show that ended with a light display of Abraham Lincoln.

And yet the dichotomy of the holiday persisted. That same year Mt. Zion Baptist Church laid the cornerstone for its new building and celebrated with a 75-car motorcade through the streets of Tulsa. But the church’s previous building, once the most opulent in Greenwood, had been burned to the ground by white rioters during the 1921 race massacre, and the church had spent decades raising the funds to rebuild. Tulsa’s mayor at the time, George Stoner, acknowledged none of this when he spoke at Carver Stadium to a black audience. He argued that “race issues would die a natural death” in due time. Greenwood’s leaders didn’t agree–at the time, the neighborhood’s chamber of commerce was planning to sue the city over unequal park services for black and white residents.

During the 1963 Juneteenth, at Greenwood’s Vernon AME Church, civil rights pioneer Clara Lupeer recounted how she and youth activists had staged some of the earliest lunch counter-sits at white restaurants in the United States and successfully desegregated many public facilities in Oklahoma City. Her young co-conspirators waved placards with democratic slogans as they entered the church, singing “Freedom” and “We Shall Overcome.”

Juneteenth has always been a time for both celebration and community organizing in Tulsa, in part because the city has always kept the meaning of the occasion top of mind. “Information might not have been in written books, but we did have teachers that would explain to us why we were celebrating,” says Maxine Horner, a lifelong Tulsa resident who served as a state senator from 1987 to 2005. “Coming out from under slavery, thats’ a moment in time you don’t ever want to forget.”

In 1989, Horner secured a grant through the state arts council to fund Juneteenth on Greenwood, a revival of the festive spirit of the holiday in earlier eras. Artists such as Ernie Fields and Lowell Fulson performed at the inaugural event. The celebration was so popular that the next year it was expanded to two days. In 1994, Horner pushed the legislature to pass a law declaring Juneteenth a state holiday.

Steph Simon was born decades after the Juneteenth celebrations Horner remembers fondly from her youth, but he has his own treasured childhood memories of the annual events the state senator helped organize in the 1990s. “It was just so fun seeing so many black people out and celebrating,” he says. “It was basically our July 4th.”

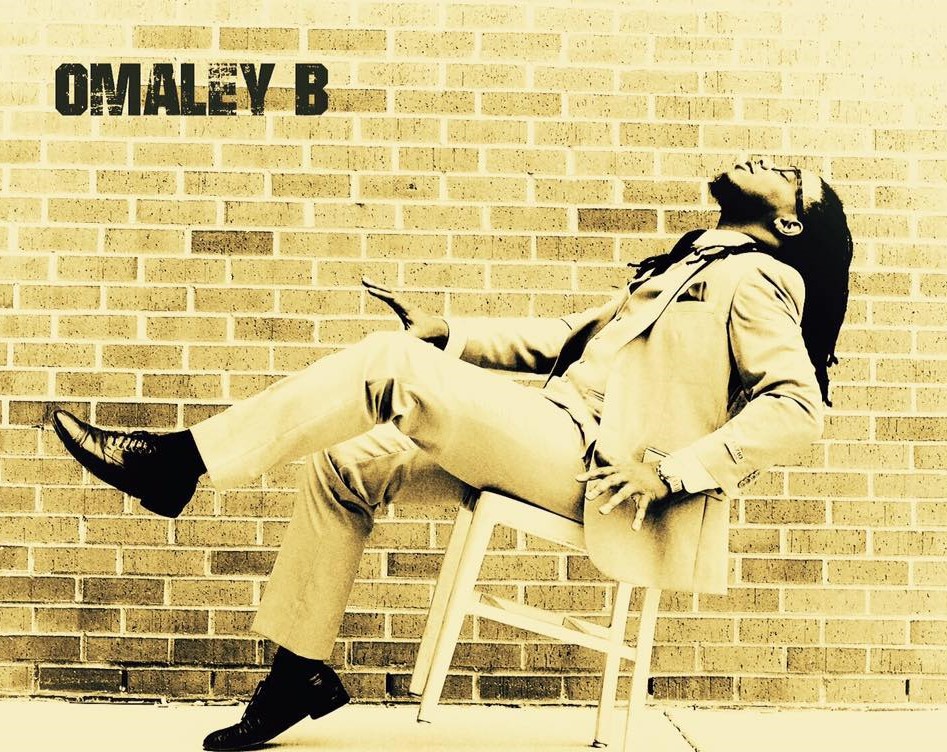

Simon, a hip-hop artist who weaves narratives about Tulsa history into his rhymes, performed at his first Juneteenth show in 2017.He views stepping onto the Juneteenth stage as a rite of passage for any Tulsa musician. “It’s like if you’re from Harlem or New York, you wanna touch the wood at the Apollo,” he says.

This year may well be the biggest Juneteenth in recent memory. Though the events were originally cancelled due to COVID-19, President Donald Trump’s announcement that he would be visiting Tulsa during Juneteenth weekend prompted North Tulsa leaders to quickly stage some counterprogramming. The “I, Too, Am America” rally will feature live music, poetry reading, a zone for kids’ entertainment, and a keynote speech by Rev. Al Sharpton. “This year we’re coming united,” says Sherry Gamble Smith, president and co-chair of Tulsa Juneteenth Inc, which has organized the holiday celebrations in recent years. “This is the community pulling themselves together and making it happen. Celebrating justice and freedom.”

The aspects of Juneteenth that stretch back to the heyday of Black Wall Street live on. Black cowboys are still participating in rodeos, such as the Juneteenth Rodeo which takes place on Saturday night at McCarty Park in Owasso. Musicians are still taking to the stage and the streets throughout the weekend. And community activism – the willingness to speak truth to power with thousands of voices at once – will certainly be on display in response to President Trump’s arrival.

On Friday Rollerson will be playing music in celebration and educating others on the reasons to rejoice, just like he always does at this time of year. “Our concern is concentrating on the black experience,” he says. “We have the right to celebrate the African American culture. And that’s what we’re going to be doing.”

Victor Luckerson is a freelance journalist living in Tulsa as he works on a book about the history of Greenwood. To view his newsletter with updates on his research, visit Run It Back at runitback.substack.com.