www.blockclubchicago.org

Roy Rogers. Gene Autry. Buffalo Bill. When you think of a cowboy, odds are you think of a white man. But Chicago’s community of black cowboys have been here all along.

SOUTH SHORE — Aaron Baxter’s path to becoming a cowboy began with a Bible illustration.

Even before his first birthday, his mother Sharon Baxter would read to him out of a children’s Bible in their South Shore home. Whenever they reached the story of Moses and the bronze serpent, Aaron would point and laugh at a portrait of bucking horses above the text.

That single page grew into a childhood obsession. She bought him horse stickers, books and VHS cassettes; she took him to the South Shore Cultural Center to see the mounted patrolmen; she let him watch every rodeo that came on television.

If Aaron Baxter, now 25, wasn’t already destined to become a cowboy, his fate was sealed when he first saw live bull riding at the old International Amphitheatre near the Union Stock Yards at the age of 3.

“He came home riding everything — the arm of the chair, the backs of me and my mom,” Sharon said. “As soon as he saw her, he would say, ‘Get down, Grandma! Get down!’ And she would get on the floor and pretend she was the bull.”

Two decades later, Aaron is an experienced horseman, a certified bull rider and one of a close-knit group of black Chicago cowboys.

As the national media became interested in the contributions of black American cowboys, the Baxters and others in the city’s cowboy scene wonder what’s taken so long.

After all, they’ve been crafting their own histories — in a town that’s far from a cowboy destination — for decades.

“Coming from South Shore, that’s considered Terror Town. I feel like I bring that with me when I get in the chutes and get on a bull,” Aaron said. “That’s something that I can’t let go of; it’s something I’ll never forget. This city made me who I am.”

‘A camaraderie that you can’t explain’

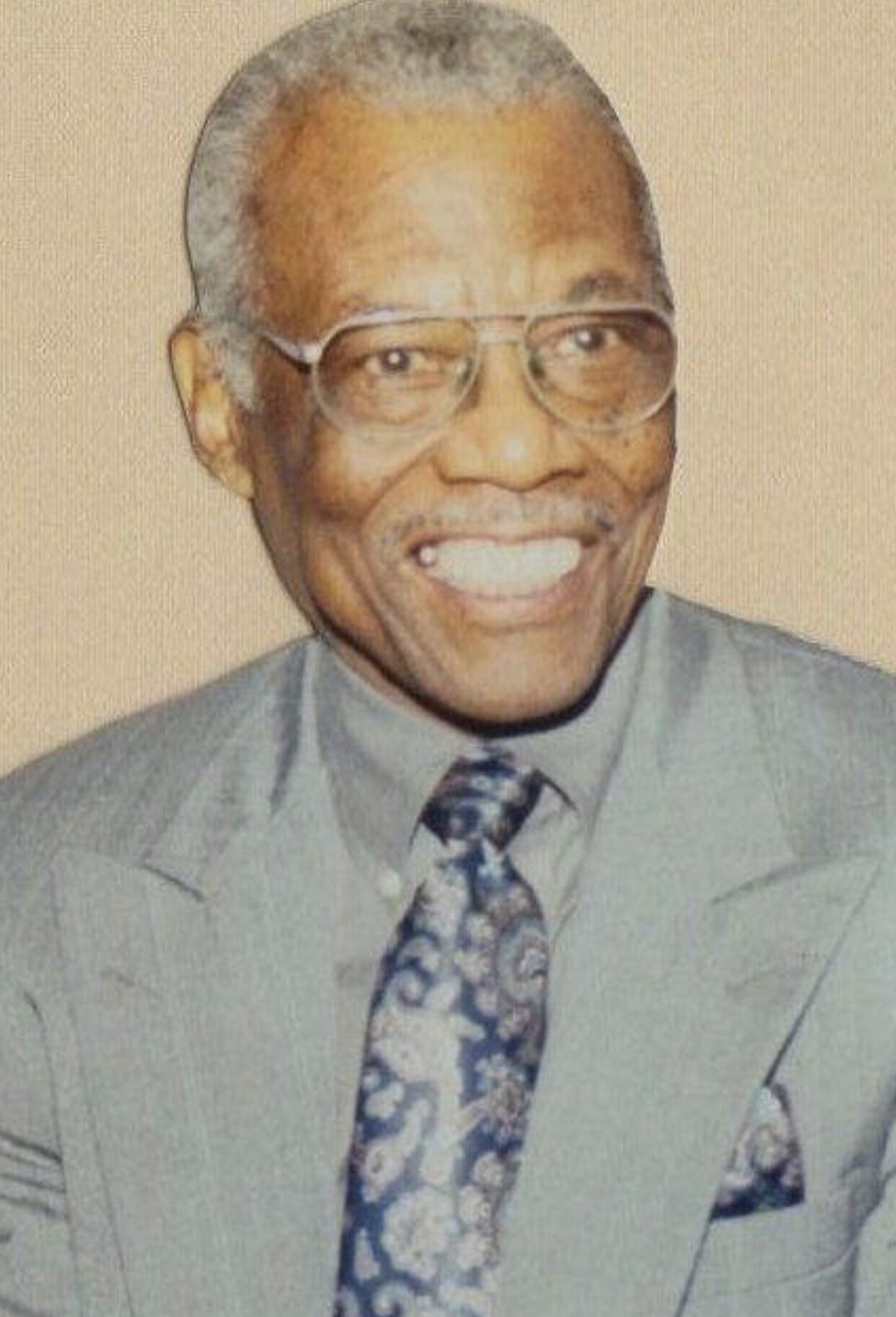

Ron Vasser, a retired television director who spent 33 years with CBS Chicago, met Sharon and an 18-month-old Aaron at the South Shore Cultural Center’s first-ever rodeo, which he organized.

Since then, Vasser has become Aaron’s “unofficial” godfather, serving as a model for living a Western lifestyle in the Midwest’s largest city.

“My mission is to help [Aaron] become a global citizen, a global cowboy,” Vasser said.

Through Aaron and others, the work of Vasser and his peers is still being reflected through Chicago’s cowboys generations later.

Korey Flowers, a 15-year-old cowboy from Auburn Gresham with the Broken Arrow Riding Club, fell in love with horses when he was 3 years old.

He paid attention as his family members woke up every morning, cared for their horses and headed off to their 9-to-5s before returning to ride.

Flowers credits his family, South Shore’s Broken Arrow and his horse, Calypso, for teaching him “mind skills, commitment and dedication.”

Broken Arrow mainstay Hollywood — a mentor to Aaron, Korey and countless others who have come up through the riding club — said Flowers’ story is not unique.

Hollywood believes there’s no better way to instill patience and respect in young people than through training a horse.

“If you know to treat this beast, you’ll know how to treat your fellow man,” Hollywood said.

Numerous young cowboys and cowgirls at the riding club’s 30th annual High Noon ride had similar sentiments.

Whether riding horses was a way to stay busy or a family tradition generations in the making, many riders credited it with helping them build their sense of character.

Aaron has worked to pay forward the guidance he’s received from his cowboy elders, volunteering time with younger riders through the riding club.

His efforts go beyond the rodeo scene too. He coached basketball until 2016 and was a substitute teacher for two years at St. Philip Neri Catholic School, where he attended until eighth grade.

More than the blocking of their hat or the quality of their boots, that sense of solidarity and reciprocity is what defines “the cowboy way,” Vasser said.

Fellow cowboys “may not know each other, but if anyone gets in trouble, you’ll always be there for them,” he said.

Before retirement, Vasser and his wife, Elizabeth, spent decades in the world of film and television with Elizabeth’s talent agency representing Jane Lynch and John Cusack and Ron producing news shows. But if you catch them at Timberland Ranch near Sauk Village, shop talk is off-limits.

“Nobody at the barn could ever ask me about working or being an actor,” Elizabeth said. “What my profession is has nothing to do with my being out here.”

When they’re with their horses, Scout and Diamond Rio, they’re not a television producer or a talent agent.

They’re just a cowboy or a cowgirl with an obligation to care for their horses and those around them.

“Horses have magic,” Ron said. “They’ve always been important, from hundreds of years ago until today. … Over all those years, our appreciation of the horse has been consistent. Once you bond with a horse, there’s nothing like it.”

Modern Trends, Ageless Roots

For those who have been hiding under a rock, recording artist Lil Nas X’s cowboy-influenced song, “Old Town Road,” spent the summer smashing the Billboard record for the longest-running No. 1 single — while smashing stereotypes.

The song’s chorus, “I’m gonna take my horse down to the Old Town Road, I’m gonna ride ’til I can’t no more,” could be heard everywhere.

Other black artists like Solange and Megan Thee Stallion also incorporated Americana into their mainstream hits.

big love to the legendary hall of fame trick roper Rex Purefoy….83 still roping round the sun like tomorrow dont exist! http://apple.co/WhenIGetHomefilm …

In fact, he said he’s “always happy” to see pop culture put someone new on to a way of life he’s always pursued.

“I feel kind of famous,” Flowers said. “Usually black kids don’t even think about doing things like this.”

Ron Vasser knows some of his cowboy friends are purists who take issue with their lifestyle being appropriated.

He isn’t completely sold on Lil Nas X’s music himself, but he welcomes any opportunity for black youth to discover the history he missed out on as a child.

“I recently went to an event on the South Side, and when they played [‘Old Town Road’], every little black kid there did some country dance moves,” Vasser said.

The song’s popularity “gives them a little more license” to dream of being a cowboy or cowgirl, he said.

Vasser has researched black cowboys since the early 1970s. That’s when a high school friend, Lamont “Rocky” Watson, moved away from Chicago “to be one of the first black cowboys out West” — or so they thought.

Once Watson arrived in the Southwest, he relayed just how wrong their assumptions were. Black ranchers, ropers and riders were no rarity; they lived right alongside their white counterparts, Vasser said.

The depth of that culture was a revelation, even for two black men who had always aspired to be cowboys. Vasser said the experience proved how the history of the West — and the history of America itself — has been whitewashed.

Vasser believes his generation could’ve developed a more inclusive definition of “the American spirit” if he’d grown up with visible black cowboys to complement icons like Roy Rogers and Gene Autry.

“If that had happened, black kids would have a different feeling and idea about themselves, and so would other whites about blacks,” Vasser said.

Instead, “it’s like this country just happened, and we were the slaves who didn’t do nothing,” he said.

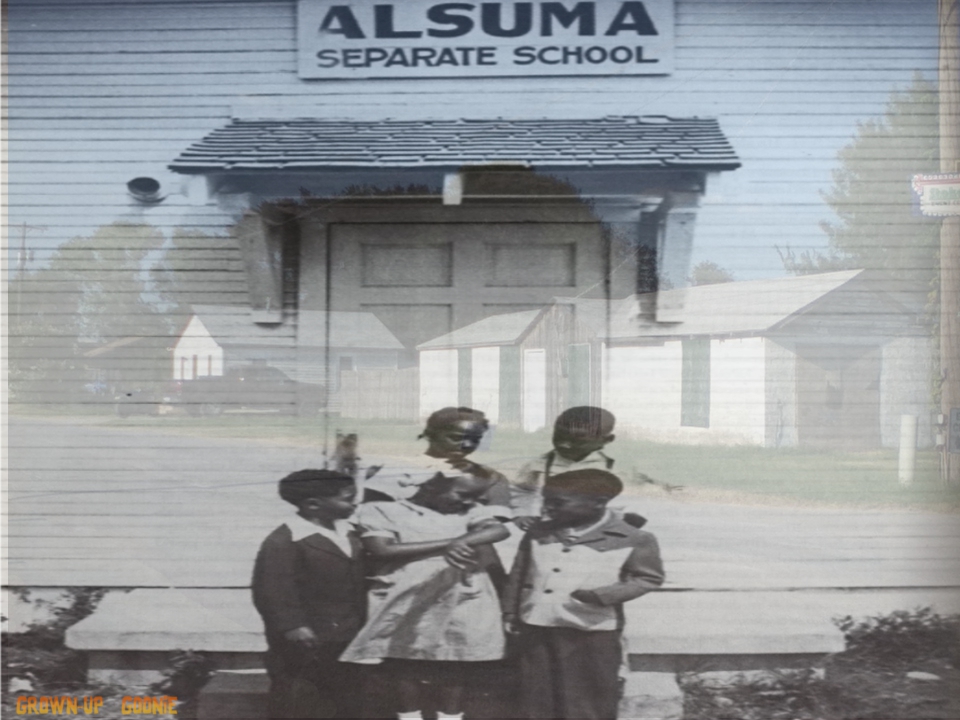

Sharon Baxter knows firsthand about the role of Black ranchers in American history. Some of her earliest memories are of her grandfather riding his steed around Itta Bena, Mississippi.

Horses didn’t spark young Sharon’s interest like they would later spark her son’s.

“My sister and I were terrified, being two kids from Chicago,” she said.

It was only through Aaron’s childhood obsessions that she understood her grandfather’s role in an overlooked part of history.

“For a while, it was a lost thing. People didn’t talk about Westerns and dressing that way,” Sharon said. “My son was the only kid in preschool dressed like a cowboy.”

Sharon is glad today’s kids can reconnect with their roots through a chart-topper who wears cowboy boots and sings with a country twang.

She’s gladder still that her son did that for her, years before Lil Nas X took the nation down Old Town Road.

“I thank Aaron for making me aware that I come from that,” she said.

‘Chicago made a bullrider’

For Aaron, the relative rarity of a black Chicago cowboy has paid off on a personal level.

It’s allowed him access to an intimate community and mentorship from Vasser, Hollywood and Broken Arrow founder Murdock, The Man With No First Name.

The Baxters have gone “behind the chutes” at United Center PBR (Professional Bull Riding) events year after year, often at the invitation of the organization’s leadership. They’ve mingled with pro riders’ families with the best view in the arena.

Bull-riding superstars like Ty Murray and Cody Custer remember Aaron’s name every time they see him, Sharon said.

“Those are things you’ll never forget,” Aaron said. “That’s the equivalent of Michael Jordan knowing you by name or Kobe Bryant asking you to come over and shoot baskets.”

Professionally, it’s a different story. Aaron refuses to cash in his connections with pro riders to further his career.

“I’ve built up relationships with guys considered legends in the sport,” he said. “I’ve been following those guys from 18-year-old rookies to grown men with families. I’m grateful and that pays off enough.”

That conviction isn’t making his career goals any easier to achieve.

Aaron works part-time at Gamestop, where he’s stayed for more than three years because its flexible schedules allow him to pursue rodeos as often as he can.

But the job barely pays enough for him to carpool to nearby events, and certainly not for him to perform in rodeos outside the Midwest.

That’s the biggest obstacle to becoming a professional bull rider in Chicago, Aaron said. “It’s not a question of if I’m able or healthy enough. It’s just about getting there.”

Yet he won’t be moving to rodeo hotbeds like Texas or Oklahoma any time soon, even if there are “seven [ranches] within 30 miles of each other to practice.”

“It’s difficult to get that niche coming from Illinois, but I’m a Chicagoan to the bone. I want to do this in Chicago,” he said. “The only Bull we know about is Michael Jordan. I want to do something with real bulls as well.”

Achieving his dream of joining Murray and Custer in PBR lore seems distant for now. But as he continues to train, hustle and budget for future glory, he has the support of the city’s cowboy scene behind him.

“It’s not every day you see a young African-American man with the heart and the passion to do this,” Vasser said. “When one comes in front of you, you recognize it and you want to help.”

Aaron’s pursuits have helped his entire family recognize their ancestors’ roles in building a nation’s identity — much like Vasser’s friend did for him four decades ago.

Thanks to mainstream trends, “there’s now an availability to the idea” that black cowboys are not and were not rare, Aaron said. “That opens the door to history.”

It’s hard to say Sharon saw all of this coming when her son first laughed at the silly horses on his Bible page.

“He’s awesome, he’s my son and he is a cowboy bull-rider,” Sharon said. “I never dreamt it would happen, but I never dreamt it wouldn’t happen, either.”

Do stories like this matter to you? Subscribe to Block Club Chicago. Every dime we make funds reporting from Chicago’s neighborhoods.