POLITICS

Ross D. Johnson, The Oklahoma Eagle

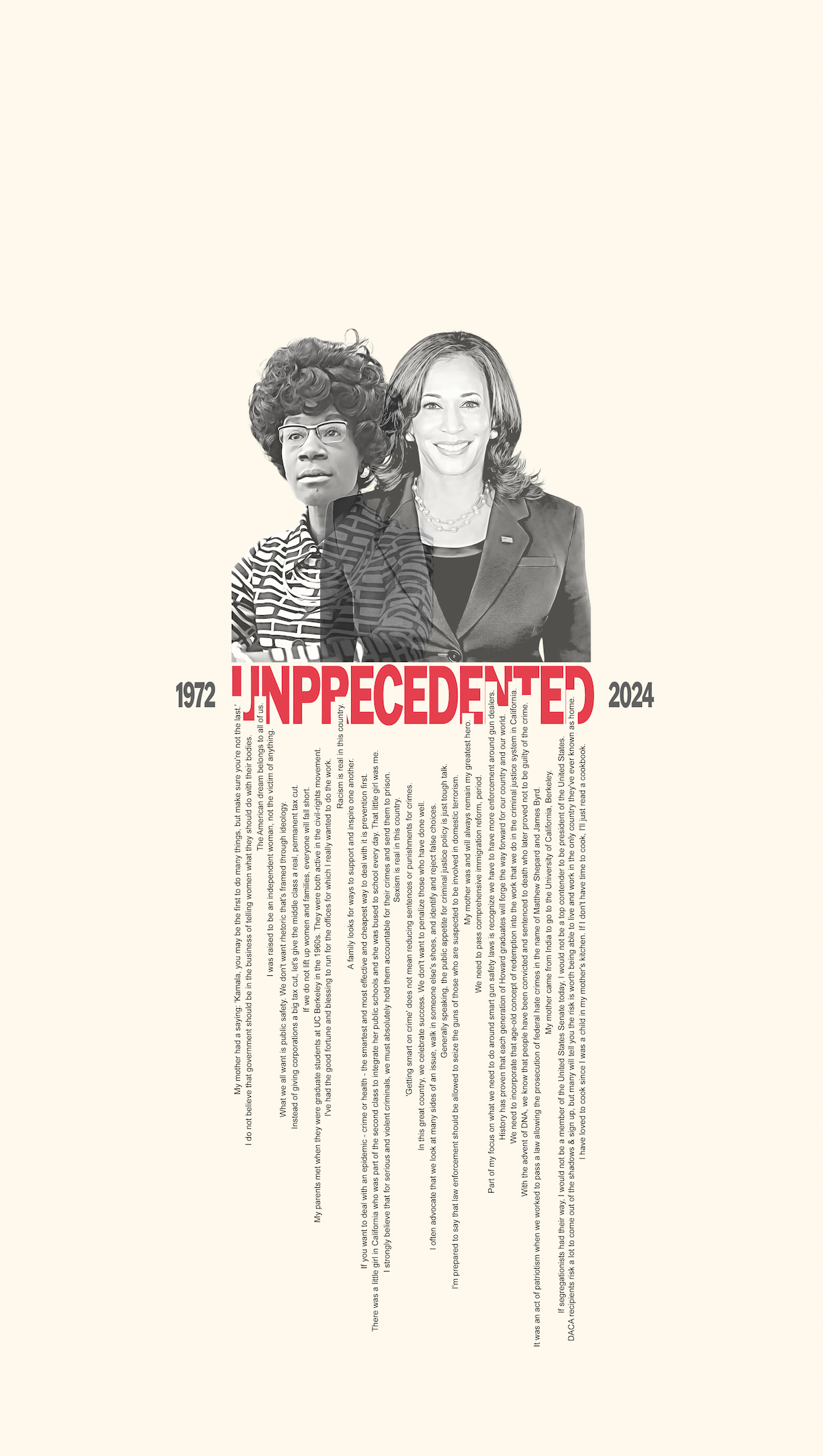

Illustration of Shirley Chisholm, who made history as the first woman to run for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination, and U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris, Democrat Party nominee for the 2024 U.S. Presidential election. Illustration, The Oklahoma Eagle

I had gotten tired of going to funerals… so much of the Movement had been tragic. You know. And I have to emphasize [Rev. Martin Luther] King’s assassination was a tragic blow to the Movement. And so four years later, March of ’72, for us to be gathering up our wherewithal to go to Gary, Indiana — hey, that was a good shot in the arm for the Movement.

Ben Chavis, National Black Political Convention, North Carolina Delegate

Richard Gordon Hatcher, the first African-American mayor of Gary, Indiana, served residents for 20 years, from 1968 to 1988. The “City of the Century”, so named as a nod towards the city’s industrial base, was home to approximately 175,000 residents, 32,000 steelworkers and governed by Hatcher.

Gary was not the epicenter of prevailing Black thought, where Black Americans voiced concerns about police brutality, voting rights, busing, foreign policy, economic investments in Black communities and political power.

Gary was neither the home of Imamu Amiri Baraka, poet, playwright, activist, educator, nor U.S. Representative Charles C. Diggs Jr., Democrat of Michigan, both co-chairpersons of the National Black Political Convention.

The industrial city, with a dominating Black American population, nonetheless became the recommended host of an estimated 10,000 people gathered to adopt a “National Black Political Agenda reflecting the interests of African Americans as a tool to run and/or endorse candidates for elective office,” according to Dr. Ron Daniels, founder and president of the Institute of the Black World 21st. West Side High School, the event venue.

Planning for the National Black Political Convention began in 1970, with organizers facing the immediate challenge of persuading city leaders to host what would soon be recorded as the largest Black American political gathering since the National Negro Congress in 1930.

The Nation of Islam’s Minister Louis Farrakhan, Nationalist/Pan-Africanists Owusu Sadaukai of Malcolm X Liberation University, Nelson Johnson of the Student Organization for Black Unity, Whitney Young, President/CEO, of the National Urban League, Coretta Scott King, Betty Shabazz, Rev. Jesse Jackson, James Brown, Harry Belafonte, Dick Gregory, and other prominent Black leaders of the era debated solutions for many of the noted challenges faced by Black Americans.

Of equal significance were assembled state, political party and national delegates, who determined the support and measure of solutions applied, how to best organize collectively, and the endorsement of a candidate in the 1972 Presidential election.

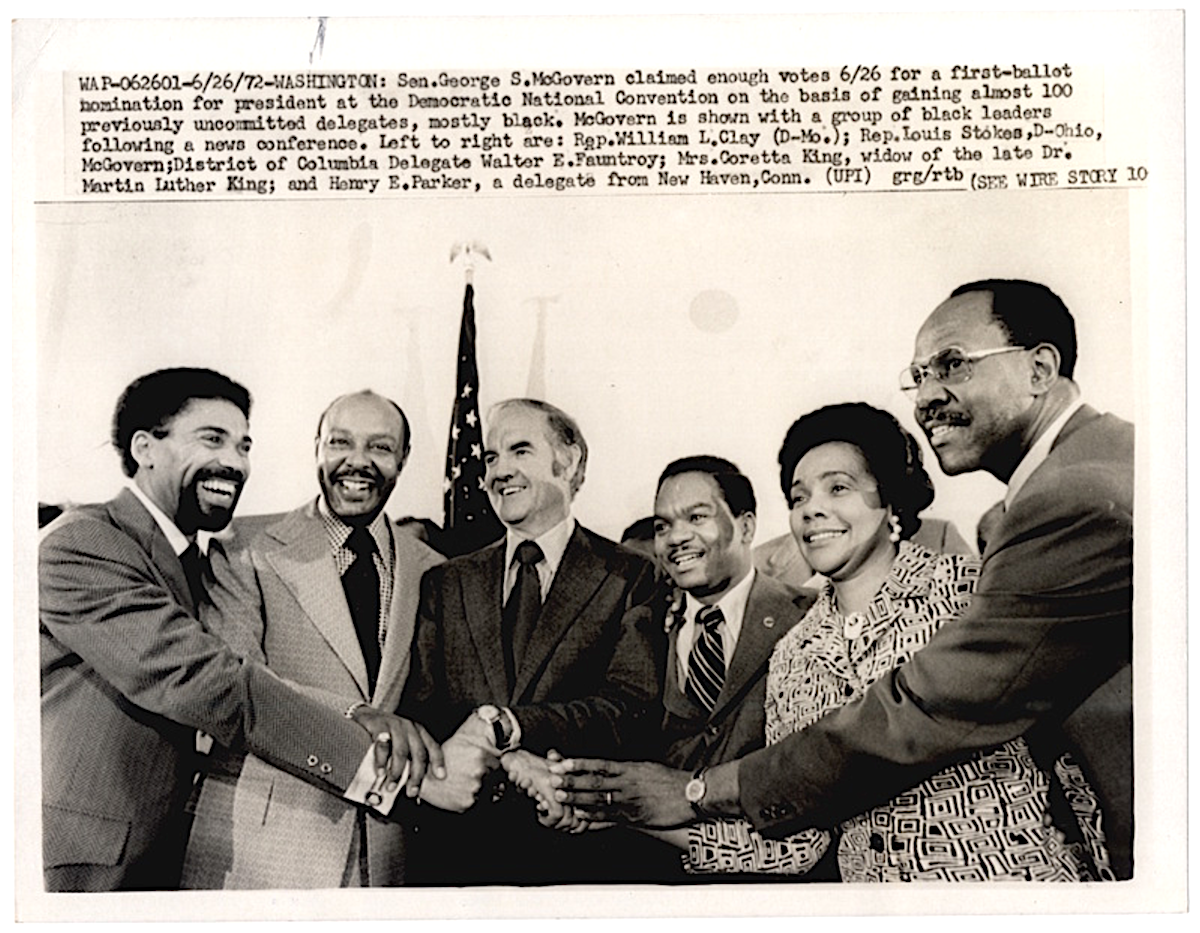

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gifted with pride from Ellen Brooks.

In the months preceding the convention, on January 25, 1972, one candidate announced their intention to vie for the Democratic Party nomination. That candidate, Shirley Anita Chisholm, of Afro-Guyanese and Afro-Barbadian descent, and the first Black woman to be elected to the United States Congress, had faced lagging support from Black institutions – The Congressional Black Caucus, which she cofounded – leading up to NBPC.

Professor Harry Edwards, sociologist, University of California Berkley, when interviewed as part of the UC Berkeley African American Faculty and Senior Staff oral history project in 2005, spoke of Chisholm’s circumstance:

“The authoritative black leadership influence and control circle tried to get her not to run. They did not feel that it was “time” for a black woman to step out and run for President. She ran without the endorsement of the NAACP, without the endorsement of the Congress of Racial Equality, without the endorsement of SCLC, without the endorsement of Operation PUSH and Jesse Jackson. She ran on her own.”

Raising and spending just $300,000 ($2.25 million present day value), from July 1971 to July 1972, Chisholm’s financial, institutional, and grassroots support now pales in comparison to Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic Party nominee for the 2024 Presidential election, who continues to garner donations totaling more than $300 million and viral public support from a broad spectrum of the electorate.

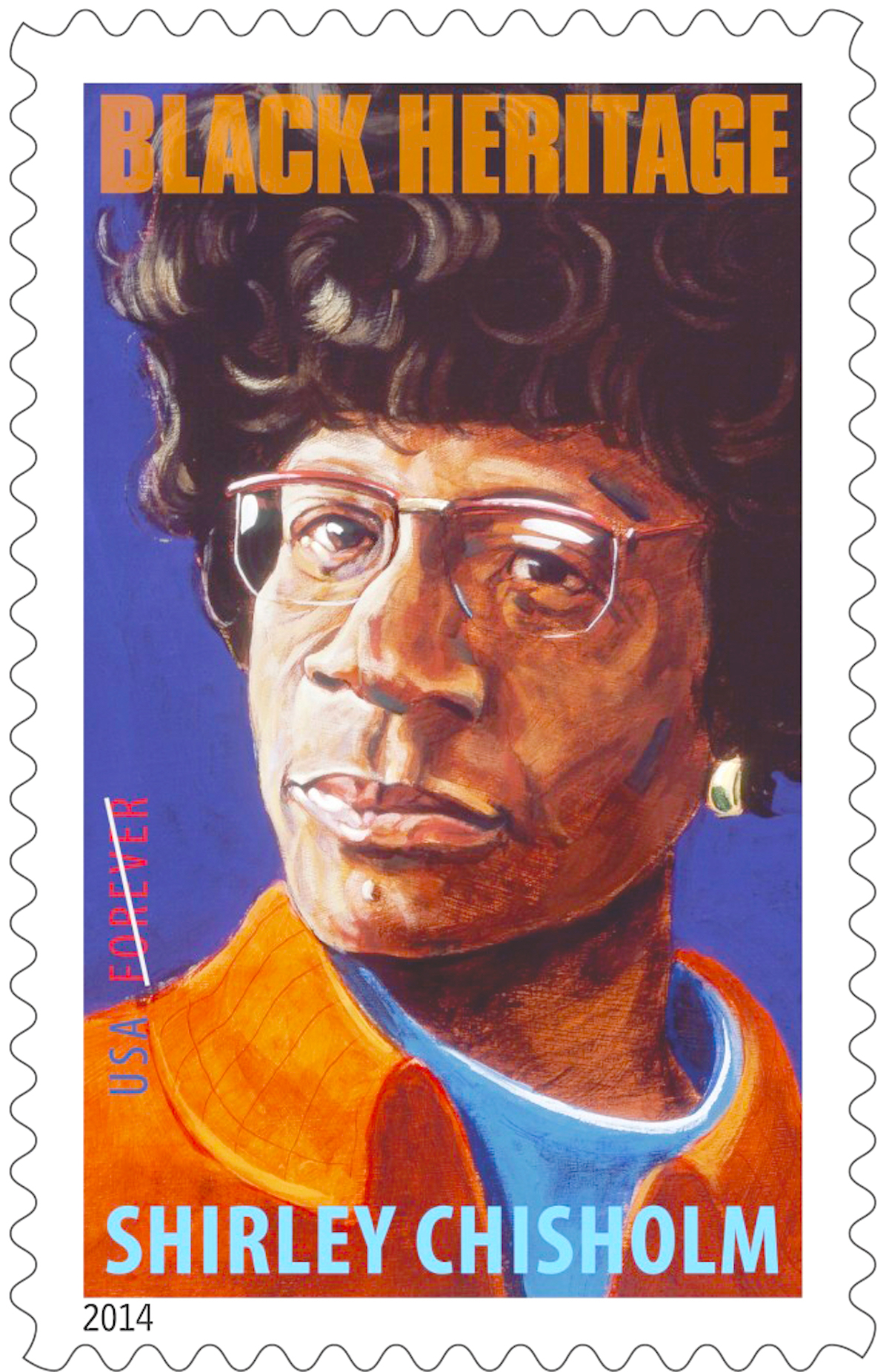

The Shirley Chisholm stamp was designed by art director Ethel Kessler and features a color portrait of Chisholm by artist Robert Shetterly. Painted in acrylic on wood, the portrait is one of a series of paintings by Shetterly titled “Americans Who Tell the Truth.” Photo U.S. Postal Service

Harris has gained political favor at a pace once only hopeful by Chisholm. For many Americans, Harris’ campaign success and the nature of her candidacy, is a reminder of the political life of Shirley Chisholm, her 1972 presidential campaign, the sharp contrast and few similarities of financial, grassroots and institutional support from all communities, Black, white and all.

In Unprecedented, The Oklahoma Eagle captured the voices of Tulsans who, enthusiastically, shared their support for VP Kamala Harris’s pursuit of the 2024 U.S. Presidential Democrat Party nomination and subsequent general election race.

The opinions gathered by The Eagle mirrored the sentiments of national polls, Democratic party officials, and independent electorate campaigns to drive funding and support.

The ubiquitous “for” campaigns, of the “Black Women for Harris,” “Black Men for Harris,” “White Dudes for Harris,” and “Republicans for Harris” varieties, evince a new enthusiasm amongst Democratic Party supporters, and disenchanted Republicans represented by former President Donald Trump, in a manner unforeseen by political pundits and historians.

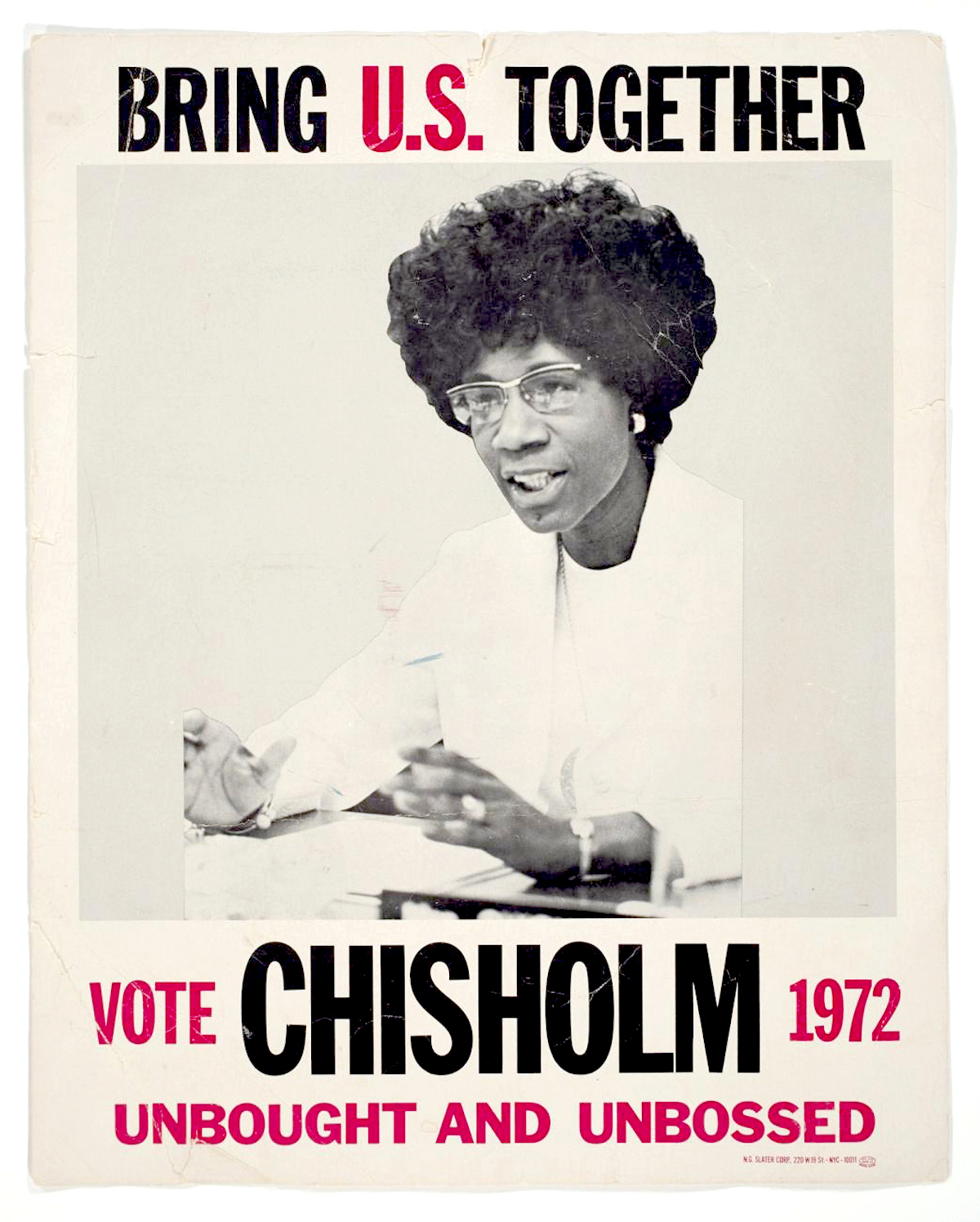

The “Unbought and unbossed” Brooklyn, New York native, Chisholm, when announcing her candidacy in Jan. 1972, broadly framed her intended appeal to voters, extending beyond race and gender. The “candidate of the people,” Chisholm, during her 14-minute announcement, represented the interests of all Americans. “I am not the candidate of Black America, although I am Black and proud”, began Chisholm, “I am not the candidate of the women’s movement of this country, although I am a woman and equally proud of that. I am the candidate of the people and my presence before you symbolizes a new era in American political history,” marking the beginning of her historic campaign.

Criticism of her candidacy was often rooted in the belief that Chisholm was not sufficiently focused on Black issues, according to Joreen “Jo” Freeman, a campaign supporter, feminist, political scientist, writer and attorney.

The California senator’s first campaign to secure the Democratic Party nomination in 2020, launched forty-seven years after Chisholm’s presidential campaign, faced similar criticism. Much of it centered on her relationship and commitment to the Black community. The point of contention with Harris is often her prior elected roles of San Francisco District Attorney and California Attorney General, and her earnest approach to prosecuting low-level drug offenses, particularly, the impact on the local Black community.

Arguments against Harris were framed as the Senator being “highly problematic for black voters,” further stating that “in both roles she did everything in her power to support the mass incarceration system and all of its foundations,” according to Black Agenda Report. The publication, and a subgroup of Black voters at the time, were committed to their opposition of Harris’ candidacy, expressed online via social media platforms, but generally conceded that her role was “what prosecutors do after all, but most of them don’t try to run for president and ask for black people’s votes.”

In spite of the vocal opposition, Harris’ institutional support was admirable. She secured the endorsements of Black & Hispanic caucus members, state and national officials, public figures and a host of notable individuals.

Chisholm’s support was grassroots-focused, comprised of feminists, individual Black voters and activists. The seated 12th congressional district U.S. Representative would not benefit from the “big picture” perspective of many Black leaders, statesmen and civil rights organizations who believed that the first Black American presidential candidate should be a man.

Few exceptions, when compared to Harris, would hold true today.

The Black Panther Party was a welcomed Chisholm endorsement, one of the few exceptions, like other matters related to the 1972 candidate, was a source of criticism.

Published in the May 6, 1972, print edition of The Black Panther newspaper, Huey P. Newton, founder and leader of The Black Panther Party fully endorsed Chisholm. He called for “all Black, poor, and progressive people across the land to support Sister Chisholm in her campaign.”

Concerns about Chisholm’s alignment with The Black Panthers appear to have informed her statement in response to the endorsement.

The Panthers, Chisholm began, “apparently came to the conclusion that in terms of their own hopes and aspirations I could be the best candidate.” She further noted that “People should not misinterpret this endorsement. After all, the Black Panthers are citizens of the United State of America and they have a right to endorse whomever they decide to endorse.”

Chisholm would not find similar favor amongst members of the Congressional Black Caucus, the organization that she cofounded a year earlier, and Black state politicians stemming from the anger of many Black politicians who viewed her decision to seek the Democratic Party nomination without their consultation or consent as a slight earlier in the year.

Seeking Black political unity, Percy Sutton, a prominent Black political and business leader, the Rev. Jesse L. Jackson, Mayor Richard G. Hatcher of Gary, Ind., Representative Ronald V. Dellums, Democrat of California, and other politicians, secretly worked to craft a solution that would ensure greater engagement with the Chisholm campaign in Feb. 1972.

A predominantly Black, 15‐ to 20‐member campaign advisory group led by Sutton, was agreed upon by Chisholm. She believed that the concession aligned with her political strategy. “I am only the instrument,” Chisholm declared, “use me as the instrument” to strengthen the collective influence of Black politicians.

Harris, experiencing a significant boost in support from both grassroots and institutional groups since assuming the top-of-the-ticket position, has been immune to similar guilty-by-association criticisms.

Former president Barack Obama and first lady Michelle Obama, the Congressional Black Caucus, House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, Rep. Jim Clyburn, CBCPAC, the political arm of the Congressional Black Caucus, Rep. Nanette Barragán, head of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus and other leading Black politicians required no more than six days to announce their endorsements of Harris’s candidacy.

Opposition to Harris’s presumed nomination is primarily focused on demands for an informal, virtual primary, affording delegates secured by Biden the opportunity to cast their support for her campaign directly. Black Lives Matter and other organizations, not specifically opposed to Harris’s nomination, have advocated for the more direct representation approach to ensure that delegates voices and agendas are reflected. How the process unfolds, leading up to the Aug. 1 delegate votes being cast, may be of increased concern to voters and the Harris campaign.

For Chisholm, the Black Panthers endorsement followed a rejection by NBPC delegates in March 1972. Declining the invitation to attend, as she believed NBPC chairs, Baraka & Diggs, would not endorse her candidacy, Chisholm’s decision proved prescient. NBPC delegates would ultimately vote to not provide an endorsement for any particular candidate for president, as reported by Soul Force (March 1972), a Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) publication.

Chisholm secured 151.25 delegate votes at the Democratic National Convention. But she did not win the nomination and later withdrew from the race.

Reflecting on her historic journey, Chisholm wrote (The Good Fight, 1973) “I ran for the presidency, despite hopeless odds, to demonstrate the sheer will and refusal to accept the status quo… I ran because most people think the country is not ready for a Black candidate, not ready for a woman candidate.”

Harris’ journey continues to be an evolving historic movement, distinctively juxtaposed with the hopes, aspirations and accomplishments of those who have paved the way before her. The months-long 2024 Presidential campaign that remains will certainly be marked by moments that qualify as unprecedented, relative to support and outcomes. Where, and how, Americans are positioned will be the subject of discussions for decades.