LOCAL & STATE

Gary Lee

1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Mural. Illustration Provided

The long pursuit of justice by the two last-known survivors of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre took a decisive blow on June 12, when the Oklahoma Supreme Court affirmed a lower court’s dismissal of their lawsuit seeking reparations.

The justices of the Oklahoma Supreme Court ruled that the plaintiffs’ grievances, including any lingering economic and social impact of the massacre, were legitimate but “do not fall within the scope of our state’s public nuisance statute.”

“The continuing blight alleged within the Greenwood community born out of the Massacre implicates generational-societal inequities that can only be resolved by policymakers — not the courts,” the ruling stated.

The Supreme Court’s decision left the last-known survivors of the massacre — Lessie Benningfield Randle, 109, and Viola Ford Fletcher, 110 – deeply disappointed. The two were children at the time at the time a white mob launched a bloody attack on Tulsa Greenwood District, destroying the community known as Black Wall Street and killing hundreds.

After years of mostly silence, they began publicly recounting details of one of the worst episodes of racial violence in American history. Their May 2021 testimony before a congressional committee was a highlight of their campaign to bring attention to their appeal for justice.

Following the ruling, the survivors and their legal representatives vowed to appeal and push forward with their pursuit of closure in the case. After decades of failed legal battles for justice in this case, many observers have begun to doubt that closure through the courts is a practical goal.

The court’s ruling appeared to underline those doubts. It sought to conclude decisively against the lawsuit that Randle and Fletcher first filed in 2020. The case centers around the survivors’ argument that the destruction of Greenwood amounted to an ongoing public nuisance that hangs over the neighborhood more than a century later. The plaintiffs sued under Oklahoma state law and not federal law. Thus, they cannot appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The plaintiffs of the lawsuit originally included another survivor of the massacre, Hughes Van Ellis, the younger brother of Fletcher. Van Ellis died in October 2023 at 102 years old.

Damario Solomon-Simmons, the lead lawyer for the massacre survivors, has argued that what happened in the spring of 1921 was essentially a “state-sponsored atrocity” and that ending the case without a trial is a blow to the notion of racial justice. The legal team plans to file a petition asking the court to reconsider its decision. It also has called on the Department of Justice to open a federal investigation into the massacre.

“Once again, the Oklahoma court system has failed the survivors. We think the decision is wrong and the reasoning is wrong,” he said in a press statement.

But Solomon-Simmons and the survivors feel they have no option but to keep fighting in the courts. The survivors “are literally living in hopes of seeing justice,” he said.

“There is no going to the United States Supreme Court. There is no going to the federal court system. This is it,” Solomon-Simmons argued in a legal brief.

His team said they plan to petition the Oklahoma Supreme Court to rehear the case and reconsider their decision.

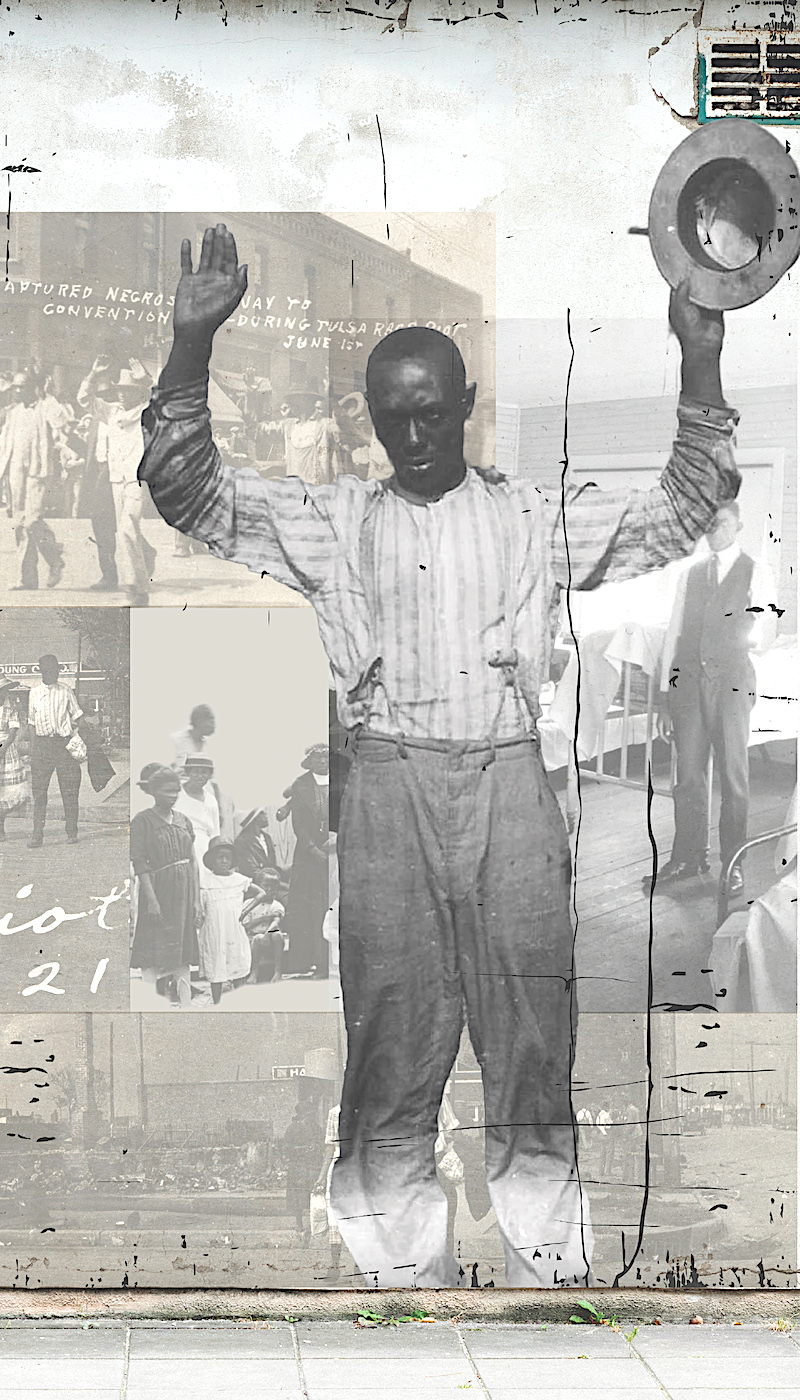

A group of Black men are marched down the street under armed guard amid the June 1, 1921, massacre in Tulsa, Okla. PHOTO University of Tulsa’s McFarlin Library Department of Special Collections

Descendants push back against the ruling

In interviews with The Oklahoma Eagle, descendants of victims of the massacre reacted negatively to the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s ruling.

“The state Oklahoma Supreme Court’s despicable dismissal of the race massacre case was also a dismissal of the humanity of survivors – Mrs. Viola Ford Fletcher, Mrs. Lessie Benningfield Randle, Mr. Hughes Van Ellis’ family – and all other survivors and descendants who sought justice over the last 103 years and counting,” said St. Rep. Regina Goodwin, who was recently elected to represent Senate District 11.

Goodwin’s ancestors were also victims of the Race Massacre. “Oklahoma is not okay,” she added. “People who perpetuate cruel injustice will answer to God.”

“I was not shocked by the ruling,” says Kristi Williams, a north Tulsa community advocate, founder of Black History Saturdays, and a descendant of Race Massacre victims.

“I expected that just considering Tulsa’s history. It is a sad day, and I wonder when we will get angry enough and how we will challenge this system. And I think the way we do that is through education. This case would be viewed and perhaps understood differently if we understood Black history, had an authentic comprehensive dialogue about Black history, and taught Black history to other races, especially white people. Not having that comprehension of history is at the root of the problem.

The City of Tulsa said it “respects the court’s decision and affirms the significance of the work the city continues to do in the North Tulsa and Greenwood communities.” The city added that it remains committed “to working with residents and providing resources to support” these communities.

And yet, no individual or body has ever been held responsible for the violent events of May 31, 1921. No responsibility has been taken for 300 estimated deaths, thousands of black residents who were assaulted, arrested, and left homeless.

Besides the allegations of a continuing public nuisance, attorneys for the survivors argued that Tulsa appropriated the historic reputation of Black Wall Street “to their own financial and reputational benefit.”

They argue that any money the city receives from promoting Greenwood or Black Wall Street, including revenue from the Greenwood Rising History Center, should be placed in a compensation fund for victims and their descendants.

The lawsuit also sought a detailed accounting of the property and wealth lost or stolen in the massacre, and the establishment of a Victims Compensation Fund to benefit the survivors and the descendants of those killed, injured or who lost property in the killings — as well as for longtime residents of Greenwood and north Tulsa.

It also asked for the construction of a hospital in north Tulsa, the creation of a land trust for all vacant and undeveloped land that would be distributed to descendants, and the establishment of a scholarship program for massacre descendants who lived in the Greenwood area.

In addition, the lawsuit requested that the descendants of those who were killed, injured, or lost property be immune from any taxes, fees, assessments, or utility expenses by Tulsa or Tulsa County for the next 100 years.