LOCAL & STATE

Gary Lee

Illustration. The Oklahoma Eagle

One evening in early February, Ray Pearcey, a Tulsa-based writer, was feeling chest pains so severe that they sent him into despair. He visited a health clinic in North Tulsa, but they turned him away, saying all their staff were busy.

By eight pm, as his symptoms worsened, Pearcey tried one last resort: Juno Medical-Tulsa, a North Tulsa health clinic that opened six months earlier on Greenwood Avenue in the historic Black Wall Street District.

Within fifteen minutes, a Juno staff member checked his vitals, performed an EKG, and determined that he was experiencing a major heart attack. Fifteen minutes later, Pearcy had checked into the Oklahoma Heart Institute, where doctors performed major heart surgery. It was the first time that Pearcy had faced significant heart challenges. But as a Black American in his 70s, Pearcey falls within a vulnerable group of people who suffer from heart issues.

“Thanks to Juno, I’m still alive,” Pearcey told The Oklahoma Eagle in an interview. He is a former Eagle editor. He had hoped that Juno would be around forever to rescue other North Tulsans.

Dashed Hopes for Juno

But Pearcey’s hope was not to be.

On Monday, February 19, a couple of weeks after Pearcy’s last visit, Juno closed its doors permanently. Patients who arrived for scheduled appointments at 21 North Greenwood Avenue on that day learned about the sudden closure from a note on the front door.

Earlier that morning, the Juno staff in Tulsa received a message from their headquarters in New York that they were closing the business immediately.

In a posting on Meta (also known as Facebook), the social media platform, Dr. Jabraan Pasha, Juno Tulsa’s executive director, said, “The information we were given was Juno Headquarters lost support from a major national investor, which significantly impacted the company’s financials. As a result, he added, the company was suddenly closing its two newest clinics in Atlanta and Tulsa.

“The decision was no reflection of the care we have been providing to the Tulsa community,” Pasha added. “We were growing steadily and positively impacting the lives of many Tulsans. The Oklahoma Eagle has reached out to the Juno administration in New York, but we have received no response at the time of publication.

Akili Hinson, the entrepreneur and physician, founded the Juno brand with a noble intent: to offer affordable, quality, family-focused healthcare in distressed neighborhoods. In 2022, the company announced that it had received $12 million in start-up funds. Backers have included Serena Ventures, NEXT Ventures, and Atento Capital. The name of the supporter who has pulled out has not been revealed.

The out-of-the-blue closure of Juno in Tulsa has left its patients, including many with dire medical needs, in a lurch. Susan Savage, CEO of Morton Comprehensive Health Services, told The Eagle that she had reached out to Pasha, the executive at Juno, offering to provide whatever help their patients need. Juno staff have sent messages of regret to its patients, suggesting alternative care facilities in Tulsa, including Morton.

More broadly, the question surfaces as to why health care is so difficult for vast segments of the North Tulsa community?

The set of healthcare issues in the Black community has plagued Tulas for decades. Several official Tulsa agencies and reports have documented the dismal health circumstances and outcomes among the Black population in Tulsa.

The Tulsa Equality Indicators, an analysis of the status of conditions in the city commissioned annually by the city, have regularly reported the disparities The most recent Equality Indicators pinpointed the most pressing health issues affecting Black Tulsans: infant mortality, premature retirement death, cardiovascular disease, and a lack of health insurance disproportionately affecting Black Tulsans. The recently released City of Tulsa Neighborhood Conditions and Index also corroborates poor underlying circumstances in North Tulsa, in particular, that affect health outcomes. The Oklahoma Eagle has reported on food insecurity, reduced post-pandemic assistance programs, concentrations of poverty, and a lack of health insurance among African Americans in Tulsa that contribute to poor health outcomes.

The lack of health insurance among many Black Tulsans is a big part of the problem. Oklahoma’s SoonerCare (Medicaid) has been a primary healthcare insurance provider for people experiencing poverty, disproportionately minorities, since Oklahoma voters mandated the program in 2021. In 2023, Oklahoma and other states were required to recertify eligibility after a relaxation of participation during the pandemic. Over 300,000 participants lost health insurance, according to reports by the Oklahoma Health Care Authority. This included over 8,000 African Americans and thousands of children in Tulsa County from information provided to the Eagle by the agency. While specific numbers are not available for North Tulsa, where nearly 30,000 African Americans reside, thousands lost health insurance in the past year.

The health challenges facing Blacks are by no means unique to Tulsa.

The Oklahoma Health Care Authority also recognizes these disparate healthcare outcomes across the state. In 1994, the Authority created a particular office “to improve the outcomes of people of racial and ethnic minority groups that are underserved due to poor access to health care resources.”

The U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) has documented a massive disparity in a wide range of diseases that afflict and shorten the lives of the African American population. The CDC cites a “growing body of research which shows that centuries of racism in this country has had a profound and negative effect” on the health of African Americans and other people of color. The CDC lists among diseases more likely to occur in the Black population: diabetes, hypertension, obesity, asthma, and heart disease. These and other disorders shorten Black life expectancy by at least several years compared to white counterparts.

When the Juno clinic opened in June 2023, it promised to help North Tulsans address their health needs. And, by many accounts, the clinic met expectations. Patients reported easy access and manageable fees. Patient satisfaction clocked in at 95 percent, according to Pasha – remarkable for any healthcare facility.

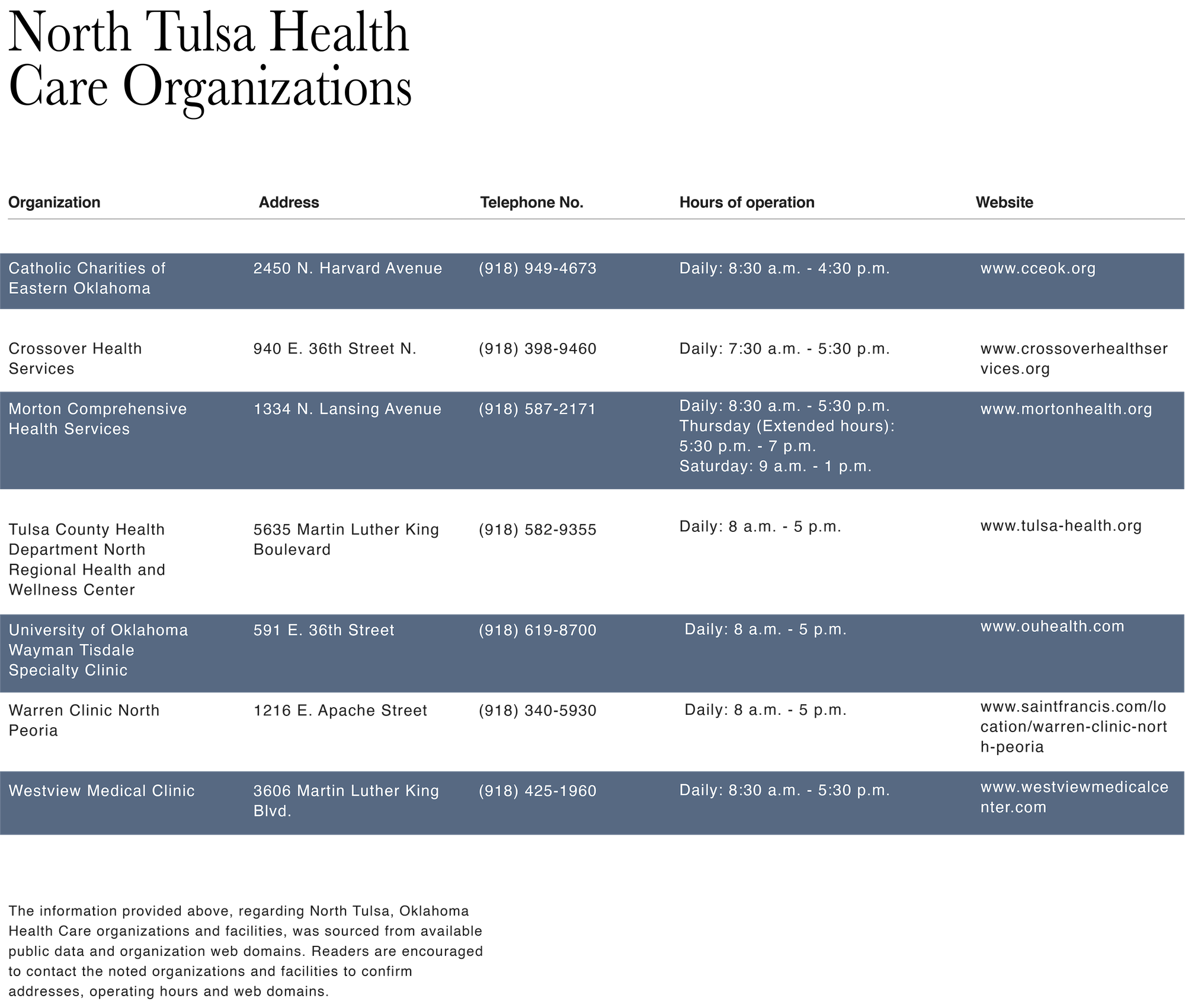

Other healthcare facilities in North Tulsa also offer a gamut of services to the community. They include Morton Comprehensive Health Services, Crossover Health Services at 36th, Westview Medical Center, and OU Health Physicians Wayman Tisdale Clinic. (See box below for detailed info)

Morton as an option for North Tulsans

Morton, whose headquarters is in the middle of North Tulsa, at 1334 North Lansing, is a viable option for North Tulsans.

Morton offers a wide range of services, including:

- Primary Care: Routine check-ups, management of chronic conditions, vaccinations, and preventive care.

- Dental Care: Dental exams, cleanings, fillings, extractions, and other dental procedures.

- Behavioral Health Services: Counseling, therapy, and psychiatric services.

- Women’s Health: Gynecological exams, prenatal care, family planning, and reproductive health services.

- Pediatrics: Well-child check-ups, vaccinations, and pediatric care.

- Specialty Care: Depending on availability and partnerships, dermatology, cardiology, and others may be offered.

- Pharmacy Services: Dispensing of medications, medication management, and counseling.

- Laboratory Services: Blood tests, urinalysis, and other diagnostic tests.

- Radiology Services: X-rays, ultrasounds, and other imaging services.

In an interview with The Oklahoma Eagle, Savage identified the top ailments that Morton treats: diabetes, obesity, COPD, heart disease, and related hypertension and high cholesterol.

But she also emphasized that Morton views itself as an entire service facility for all a patient’s needs. “In addition to treating the medical condition, we also work to get them directed again, and they have to decide they want to do this but to be part of their health care. We are what’s called a patient-centered medical home. What that means is when you come in for services, you’re going to be asked if you register as a patient, not only what is your immediate issue but what are your goals for your health care?”

Morton operates six clinics, including branches in East and West Tulsa and a location in downtown Tulsa, servicing Tulsa’s homeless population. The center, recognizing the transport challenges many Tulsans face, also offers a transport service for patients.

While Morton is engaged in outreach programs throughout North Tulsa and elsewhere in the city, Savage acknowledged some misperceptions about the facility linger in North Tulsa. Kevyn Bagby, Morton’s Director of Community Outreach, has received feedback from across North Tulsa. Savage says, “What she hears constantly is Oh, Morton, you take insurance? Oh, we didn’t think of you. We thought you only saw uninsured people or didn’t take any insurance. Oh, Morton, you’re a free clinic? Oh, you don’t have the quality providers that somebody else does. So some of that comes from misinformation from his maybe historic attitudes? I don’t know.”

Getting out in North Tulsa and providing detailed information about Morton’s offers is a big part of Savage’s agenda. “We spend a lot of time trying to say what we do so that people know they have choices,” Savage told the Eagle.

Will Juno return?

A month after undergoing heart surgery, Pearcey is on the road to recovery. Despite Juno’s closing, Pasha said the former Juno staff say they are committed to helping North Tulsans address their healthcare needs.

“The desire and need for innovative and community-focused healthcare on Greenwood is more apparent than ever,” said a statement on social media signed by Pasha and Dr. Leah Upton, a Tulsa-based physician who had helped run the clinic.

“Our team is exploring all options to reopen. We remain optimistic a solution that’s best for our community will be reached.”

Eagle staff writer John Neal contributed to this article.

TRUSTING NEWS SURVEY

Trusting News campaign members are encouraged to complete the following survey.