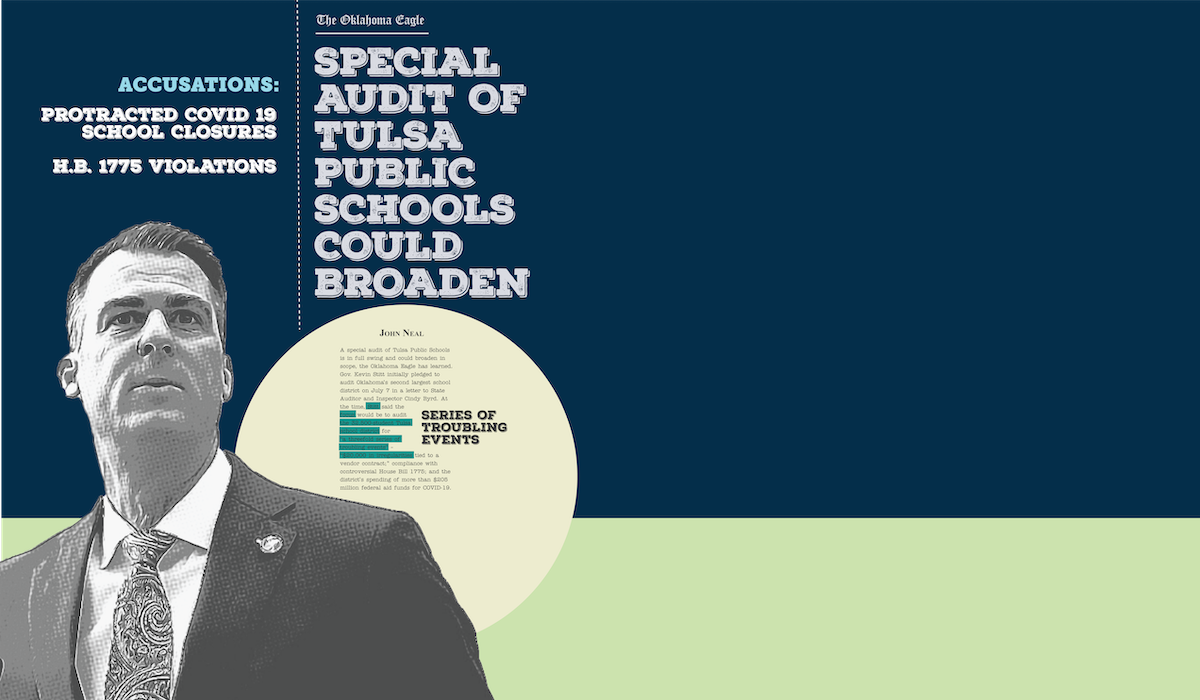

A special audit of Tulsa Public Schools is in full swing and could broaden in scope, the Oklahoma Eagle has learned.

Gov. Kevin Stitt initially pledged to audit Oklahoma’s second largest school district on July 7 in a letter to State Auditor and Inspector Cindy Byrd. At the time, Stitt said the focus would be to audit the 32,500-student Tulsa school district for “a threefold series of troubling events” – “$20,000 in irregularities tied to a vendor contract;” compliance with controversial House Bill 1775; and the district’s spending of more than $205 million federal aid funds for COVID-19.

In the three months since the governor’s request, State Auditor and Inspector spokesman Andrew Speno told the Eagle that the special audit could take other turns as “one thing leads to another” and can “balloon.” As to date, there has been no new developments to report on the special audit’s progress.

A review of “Special/Investigative Audits” official website reveals special audits commonly state that the objectives of the audit “includes but is not limited to” the initial scope. Stitt cited this same expansive language in his letter to Byrd.

For now, the special audit for Tulsa schools appears to be headed for a lengthy, complex and expensive undertaking. The audit is only the latest example of longstanding differences between Stitt and TPS officials.

Stitt’s pledge for the special audit came ominously three weeks before Tulsa and Mustang Public Schools became the first Oklahoma school districts to face consequences for violating H.B. 1775 that governs the teaching of racial and sexual concepts. The Oklahoma State Department of Education (OSDE) downgraded each school district to “Accreditation with Warning” status, a penalty more severe than the recommendation of its general counsel.

For Tulsa, the OSDE acted on a complaint filed by a white Memorial High School biology teacher, who alleged that while she participated in a diversity training session, the curriculum “shame white people for past offenses in history.”

Stitt’s request of the special audit also came on the heels of a special meeting of the Tulsa Board of Education in which Superintendent Deborah Gist discussed – in executive session – the resignation of a high-ranking school district employee “concerning a pending investigation… regarding payments made to certain District employees and financial losses to the district.”

In discussing the audit, Speno told the Eagle that for the State Auditor and Inspector’s office, “This is a big project since TPS is such a big district. It will be a while before this one is finished.”

As part of the special audit, the district will bear the expense.

Gist has said the district would “cooperate fully.”

It comes at a time when Tulsa and other Oklahoma school districts struggle to find funds to pay and retain teachers while the state provides dwindling financial assistance.

On Sept. 9, the Eagle reported that George Washington Carver Middle School, Booker T Washington High School and other schools in North Tulsa were among the 78 schools and charter partners across the city that are struggling to fill 100 teaching vacancies. The shortfall includes some positions that are critical to core content instruction.

Special audits are rare

Stitt’s motives for the special audit for Tulsa schools were made clear in a both the July 7 letter to Byrd and his Facebook posting when he linked it to Tulsa’s response to the coronavirus pandemic. The governor vehemently opposed school closings statewide and mask mandates. And in the same posting, he blasted the “indoctrination” of students in the “teaching of critical race theory.”

The school closings statewide came at a spike in COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations and deaths. Still, Stitt was miffed by the actions taken by Tulsa officials.

“Although ESSER (Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief) funds were intended to minimize disruption from the COVID-19 pandemic and support the well-being of students, TPS stayed closed over 300 days—longer than any other school district,” Stitt wrote to Byrd on July 7.

Tulsa school officials have repeatedly denied teaching critical race theory, which claims race is a social construct, and racism is interwoven into America’s institutions and policies, disproportionately impacting people of color.

To date, neither Stitt nor any other state official has provided any evidence that critical race theory is being taught in Oklahoma’s public schools.

According to a tabulation of school district special audits on State Auditor and Inspector’s website, fewer than 10% of school districts in Oklahoma have been subjected to special audits over the last 20 years. And far fewer still have been ordered by the state’s governor.

Nevertheless, Tulsa School Board members Jennettie Marshall and E’liena Ashley sent a letter on July 1 to Stitt requesting the special audit after reading a Tulsa World article. The pair wrote to Stitt, “There is significant concerns and substantiating evidence that processes and state contract laws may have been violated, and that this is not a one-time situation but a pattern of operation.”

Scope of the audit is unusual

One aspect of the audit is a “performance audit,” in which Stitt and Byrd seek to determine if Tulsa Public Schools is in comprehensive compliance with H.B. 1775. The 2021 law prohibits teaching certain concepts commonly used in diversity training.

Gist recently told the OSBE that the great diversity within the Tulsa school system made diversity training more critical, including “implicit bias” concepts that are not prohibited by the law. She noted that 78% of the public school students were persons of color. Furthermore, this performance audit goes beyond the scope of H.B. 1775 in that the law is supposed to be “complaint” based. No provision in the new law calls for comprehensive audits, nor has any been undertaken previously.

Another portion of the review is an “investigative audit,” in which Speno says an “impropriety” is suspected or alleged. The first part of the investigative audit concerns questionable payments to certain school district employees by a vendor. Gist has publicly said that the loss was about $20,000, having occurred two years prior and has already been turned over to local law enforcement officials, who are also investigating the district.

Stitt also commissioned the State Auditor and Inspector’s office to examine TPS’s expenditures of more than $205 million in federal funds for COVID-19 aid.

Oklahoma’s own issues with federal audit

In all, Oklahoma has $1.87 billion to spend under the American Rescue Plan Act, but state lawmakers complaint some projects approved last December have yet to receive funding.

These audits are typically performed by the federal government. Such a federal audit was conducted on the state of Oklahoma’s use of COVID-19 aid funds. There the federal government found multiple substantive failures in the $8 million Bridge the Gap Digital Wallet program, lacked oversight and safeguards against fraud, allowing parents to purchase miscellaneous items like furniture, televisions, watches and other merchandise when funds were supposed to provide learning materials for students, Oklahoma Watch and The Frontier reported.

The two news outlets reported that the U.S. Department of Education placed conditions on how Oklahoma could dole out its second allocation worth $17.7 million due to state officials’ lack of communication with federal monitors and inability to account for the nearly $40 million received under the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief (GEER) Fund in 2020.

The two news outlets also reported that nearly $18 million in federal coronavirus relief dollars for education has been in Stitt’s hands since January 2021 but has yet to be spent to help Oklahoma students recover from the pandemic.