The U.S. Transportation Secretary hopes to deliver on President Joe Biden’s pledge to reconnect Black communities across America.

Victor Luckerson

The Oklahoma Eagle

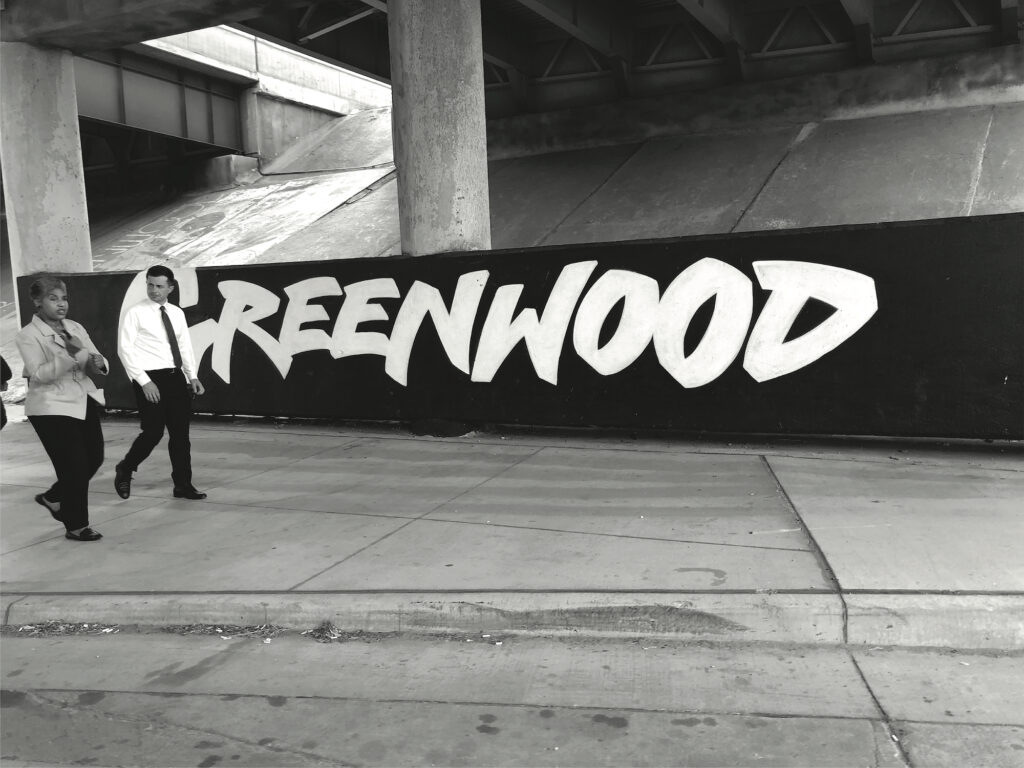

ILLUSTRATION

State Rep. Regina Goodwin concludes U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg’s tour of the Historic Greenwood District in lobby of Vernon A.M.E. church. on Tuesday, Aug. 23, 2022. Photo Victor Luckerson.

Fifty-five years after an interstate highway sliced through the heart of the Historic Greenwood District, U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg acknowledged that the federal government has “an opportunity in front of us to do things differently, and better.”

The head of the nation’s transportation department visited the Historic Greenwood District as part of a brief trip to Tulsa Tuesday Aug. 23, 2022. Buttigieg is on a multi-state tour of infrastructure projects that have recently received federal funding. He spoke earlier in the day at a press conference celebrating a new project in southwest Tulsa that will reconnect West 51st Street beneath U.S. Highway 75, thanks in part to a $10 million federal grant.

Many Historic Greenwood District residents and stakeholders hope even more can be done to transform their neighborhood. This year the Biden administration is launching a $1 billion initiative called Reconnecting Communities to undo some of the damage caused nationwide by the construction of the interstate system. The massive highways were originally built to serve predominantly white suburban commuters, at the expense of Black and low-income neighborhoods in the city core.

Local and state officials are currently considering applying for the federal grant money, with some advocating for the complete removal of the Interstate 244 overpass that has cast a long shadow of frustrations over the Historic Greenwood District since its opening in 1967.

‘Greenwood is a very unique place’

In the Historic Greenwood District, the impact of the $50 million I-244 construction along with widespread razing of homes by the Tulsa Urban Renewal Authority in the years afterward is sometimes referred to as a “second destruction” of the neighborhood, after a white mob burned the district to ashes in 1921.

Buttigieg acknowledged this full history during a brief visit to the Greenwood Cultural Center, saying that it was important to pay attention to “not just what the massacre did but what highway policy did.”

“There’s stories all over the country,” Buttigieg said, “but Greenwood is a very unique place.”

The Congress for the New Urbanism published in 2021 a landmark study “Freeways Without Futures” that noted “an overwhelming amount of evidence exists to demonstrate that highway building was a tool to perpetuate racial segregation” strategically orchestrated by predominately white-controlled local, state and federal bureaucracies beginning as early as 1939 as the Bureau of Public Roads.

The section of I-244 expressway in the Historic Greenwood District was highlighted in the study as one 15 highway projects that should be removed. To make way for the expressway, about 3,000 homes and 500 businesses owned by African Americans were bulldozed.

“Removing highways that still beset the Black and brown communities who live around them provides an opportunity to acknowledge the harmful and destructive actions taken against them over the last 70 years and repair the damage,” the study noted.

The study acknowledged that “removing I-244 will increase the connections between Greenwood’s remaining community assets and the rest of north Tulsa. Taking down the highway won’t restore Black Wall Street by itself, but can be part of a larger plan toward community revitalization.”

Following Biden’s pledge

During President Joe Biden’s June 2, 2021, visit to Tulsa to commemorate the 1921 Race Massacre, he noted how the predominately Black community on the west side of Wilmington, Delaware, suffered the same fate as Greenwood. In June, Buttigieg announced a $1 billion effort, called “Reconnecting Communities,” to rectify racist infrastructure decisions, like I-244, that bulldozed Black communities.

In Biden’s “Reconnecting Communities” plan, it notes, “Too often, past transportation investments divided communities… In particular, significant portions of the interstate highway system were built through Black neighborhoods. The deal creates a first- ever program to reconnect communities divided by transportation infrastructure.”

In his hourlong tour of the neighborhood, the transportation secretary’s visit was a follow up to Biden’s visit and pledge. Buttigieg stopped by the Cultural Center, the Historic Vernon A.M.E. Church and Tee’s Barber Shop. At Tee’s, businessowner Willie Sells told Buttigieg how life on the street changed after the bulldozers arrived in 1967.

“I was here before the highway,” Sells said, noting that he cut his first head of hair on the street in 1963 near the other end of North Greenwood Avenue and closer to East Pine Street.

“The old folks’d say they killed Greenwood… People died heartbroken because of that. What has happened is we’ve learned to live with it. We’ve learned to live around it.”

The roar of cars trundling across the interstate was constant as Sells spoke. An average of 73,300 vehicles travel along the 15.8-mile stretch of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Expressway, which was originally called the Crosstown Expressway until 1984.

Next steps

State Rep. Regina Goodwin led Buttigieg and Transportation Deputy Secretary Polly Trottenberg on the tour of the Historic Greenwood District’s landmarks. Goodwin, whose District 73 includes Greenwood, has been a vocal advocate to remove the highway.

Last year, she held an interim study in the state legislature that highlighted successful highway removal programs in other cities and this year sponsored a bill that would have provided funding for planning the redevelopment of the I-244 corridor.

“We’re talking about removal, and what that does in terms of restoring land and repurposing land,” Goodwin told Buttigieg. “It’s the right thing to do.”

Deputy Secretary Trottenberg met with Goodwin in June for an initial discussion about how the Historic Greenwood District could apply for a Reconnecting Communities grant.

On Wednesday, she held a second meeting requested by Goodwin with local and state officials to further discuss the future of I-244.

Initial applications for the $1 billion in “Reconnecting Communities” funds are due Oct. 13.

About the Contributor

Victor Luckerson is a journalist and author based in Tulsa who works to bring neglected black history to light. He is a former staff writer at The Ringer and business reporter for Time magazine. His writing and research have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Wire, and Smithsonian magazine. In 2021, he was nominated for a National Magazine Award for his reporting in Time magazine on the history of the 1923 Rosewood Massacre. He also manages an email newsletter read by thousands of subscribers about underexplored aspects of black history, called Run It Back.