TRES SAVAGE AND JOE TOMLINSON, OKLAHOMA NON DOC

Leaders of the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs have invited representatives of the Five Tribes to testify at a July 27 hearing on the status of their Freedmen, the descendants of slaves formerly held by the Muscogee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole and Cherokee nations.

But it’s unclear whom each tribe may send to testify before the committee. A prominent Freedmen advocate is frustrated by the hearing’s proposed schedule, which does not include Freedmen representatives from the four tribes that have yet to recognize Freedmen as full citizens. Only the Cherokee Nation currently recognizes its Freedmen as full citizens with complete access to tribal benefits.

“The biggest issue to me is that they give the Freedmen two weeks’ notice, but they told the tribes a month ago,” said Eli Grayson, a Muscogee citizen with Freedmen ancestors who has been a vocal critic of his tribe and the other three tribes that do not grant Freedmen full citizenship.

McGirt Ruling Draws Attention to Freedmen

With all Five Tribes’ historic Indian Country reservations affirmed following the July 2020 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma, the topic of how tribes treat their Freedmen has drawn additional attention and scrutiny from Freedmen advocates and, in particular, Congresswoman Maxine Waters (D-CA43).

Waters is the chairwoman of the House Financial Services Committee and has filed House Resolution 5195, which seeks to tie federal funding for tribal housing and infrastructure to compliance with the 1866 treaties, which stated in one capacity or another that the Five Tribes would grant rights and privileges to the descendants of their former slaves.

On July 27, 2021 — one year prior to this year’s proposed Senate committee hearing — a subcommittee of Waters’ committee held a 90-minute hearing about tribal Freedmen. Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. and Cherokee citizen Marilyn Vann, the president of the Descendant of Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes Association, both testified.

“I was honored to go before the House of Representatives last year and share my views on Cherokee Nation’s obligations to our enrolled citizens of Freedmen descent, and I look forward to continuing the discussion next week before the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs,” Hoskin said in a statement to NonDoc. “Cherokee Nation is a better nation for having recognized full and equal citizenship of Freedmen descendants, and we work every day to ensure we are upholding the solemn promise our ancestors made to Cherokee Freedmen and their descendants in 1866.”

Vann, who became the first Freedman descendant to hold office in the Cherokee Nation after being appointed by Hoskin, said the Senate committee has offered her five minutes to testify about the history of Freedmen in all Five Tribes. She said she was first contacted July 12 about testifying. Asked about being the lone Freedmen representative set to testify at the Senate hearing, Vann said she was surprised.

“Since God has allowed it to happen this way, God must feel that I’m up to the task,” Vann said.

“This is a hearing on how the Indians can kick out the Blacks”

Grayson expressed less faith in the set-up.

“This whole shitshow isn’t what we actually agreed to. We agreed to have a hearing with the Freedmen of all Five Tribes to talk about their issue before the Senate Indian Affairs Committee,” Grayson said. “Instead, they drove all Five Tribes in with their own representatives from their side.”

During a spring phone call with congressional staff members regarding Waters’ bill, Grayson said Freedmen activists were asked to “back off” their rhetoric and public criticisms.

“So the Senate came back and said, ‘Hey, we’ll do a hearing for you if you just back off the pressure.’ Because we’ve had Black Lives Matter, everybody involved in this,” Grayson said. “We said, ‘OK, we finally get a hearing in the Senate. We’ve been waiting 100 years for that and this would be right.’ But instead, this bait-and-switch shit of inviting everybody but the Freedmen to testify is not a Freedmen hearing. This is a hearing on how the Indians can kick out the Blacks.”

Grayson said Muscogee, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Seminole Freedmen groups “have their own speakers” who deserve an opportunity to tell their stories to senators because their histories “are different.”

“Like in politics, this is the shit that happens,” Grayson said. “The Freedmen needed their own hearing and not a clutter — a beef stew of the tribes talking about how they want the Blacks out.”

Waters’ office declined to comment today on the planned Senate hearing. It has yet to be posted to the Committee on Indian Affairs’ website or calendar. The communications director for Sen. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii), who serves as the committee’s chairman, did not respond to a request for comment prior to the publication of this article.

Lankford declined comment

Sen. James Lankford (R-Oklahoma) also serves on the committee. Asked about the committee’s proposed hearing Monday, a spokeswoman for Lankford said she was unaware of its scheduling. On Tuesday, she said Lankford typically does not make statements ahead of hearings.

Leaders of the Cherokee, Muscogee, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Seminole nations have all been invited to testify at the hearing, multiple people have told NonDoc.

Choctaw Nation director of public relations Randy Sachs said the Choctaw Nation will have a representative at the Senate committee hearing, although the exact person has not been determined.

Seminole Nation Assistant Chief Brian Thomas Palmer said he is unsure who will testify on behalf of his tribe.

“You know, the Freedmen issue is always the elephant in the room,” Palmer said. “We’re going to ride in on it next week and see what happens.”

Palmer provided an additional statement on behalf of the Seminole Nation.

“The Seminole Nation follows the treaty and constitution with an understanding of how it was constructed and what was intended just the same as we view the U.S. Constitution,” he said.

‘People need to know about what goes on here in Oklahoma’

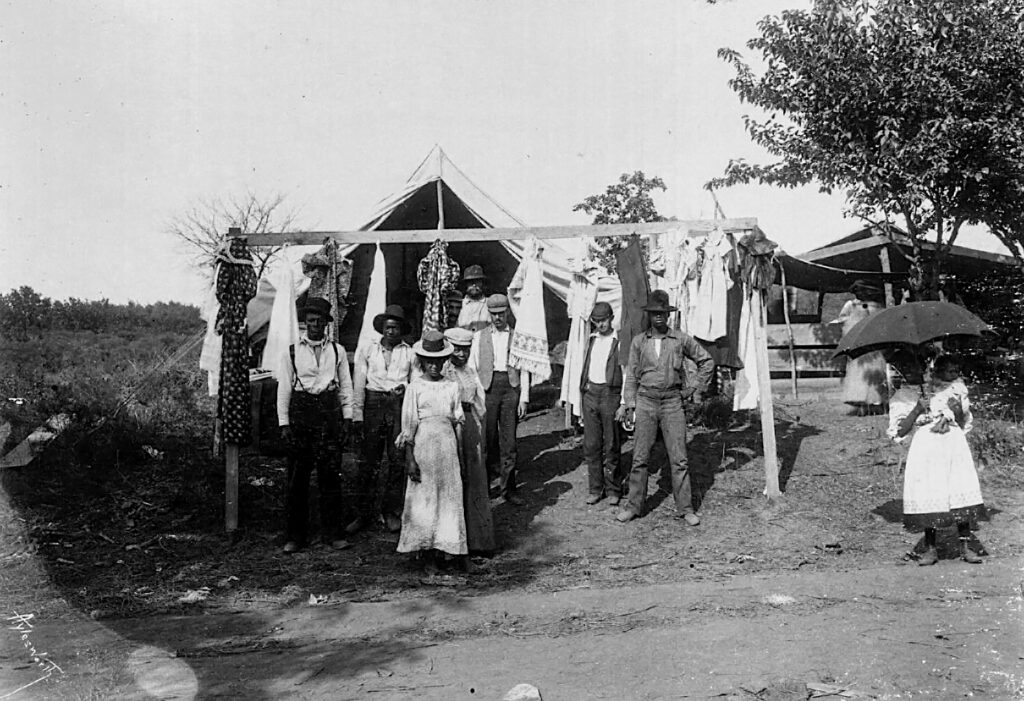

Freedmen are descendants of enslaved people brought to Oklahoma by tribal nations, which were forcibly relocated here in the 19th century by the federal government.

The United States signed treaties in 1866 with the Cherokee, Muscogee, Choctaw, Chickasaw and Seminole tribes which granted reservation land to each tribe and abolished slavery within the tribal nations. According to those treaties, former slaves were to be recognized as full tribal citizens.

Today, however, only the Cherokee Nation recognizes its Freedmen as full citizens, after its “by blood” language was removed by a unanimous ruling from the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court in February 2021.

The Muscogee, Choctaw and Seminole nations have since amended their constitutions in ways that exclude Freedmen, and the Chickasaw Nation never enrolled Freedmen into the tribe at all, despite treaty stipulations.

Without full citizenship within tribal nations, Muscogee, Chickasaw and Choctaw Freedmen descendants are not allowed to vote, run for office or benefit from tribal services such as housing, education and health care, many of which are heavily funded by the federal government.

The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma grants only limited citizenship to its Freedmen, allowing them to vote, sit on governmental committees and hold office on the tribe’s General Council within the tribe’s two Freedmen bands: Dosar Barkus and Caesar Bruner. But Seminole Freedmen are not eligible to hold senior leadership positions or receive a number of services.

In October 2021, the federal Indian Health Service announced that Seminole Nation of Oklahoma Freedmen are eligible for health care, after months of reports that the tribe was denying Freedmen COVID-19 vaccines.

Ivory Vann, a Muscogee Freedman and a member of the Muskogee City Council, said he had heard “a little bit” about the planned U.S. Senate committee hearing. He called it “long overdue.”

“Just in general, people need to know about what goes on here in Oklahoma,” Vann said. “How would you feel? You got five kids, and one gets steak and the other ones get beans? That’s how I feel with the Cherokee Freedmen.”

Ivory Vann, who is not related to Marilyn Vann, said the Muscogee, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Seminole nations “still have got to go by that treaty.”

“They’re supposed to, but they don’t,” he said.

Grayson, who described himself as “a shit stirrer” who has fought for Freedmen inclusion over the last 25 years, took issue with the lack of public communication and discussion about the upcoming Senate Freedmen hearing, which is scheduled for 2:30 p.m. eastern time Wednesday, July 27.

“The beginning of the conversation was — they didn’t come out and say it, but they kind of hinted — ‘Less press is better.’ And that raised feathers on me like you wouldn’t believe,” he said. “I was like, ‘What do you mean less press? What the fuck is that?’ That means you’re doing something sneaky.”

Marilyn Vann was more diplomatic.

“I want to say I am grateful that there is going to be a hearing, but in my 20 years of advocacy for Freedmen, there have been a lot of things that have seemed strange to me,” she said.

How To Watch The Hearing

WHO: U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs

WHAT: Oversight Hearing on Select Provisions of the 1866 Reconstruction Treaties between the United States and Oklahoma Tribes

WHEN: 1:30 p.m. CST, Wednesday, July 27

WHERE: Dirksen Senate Office Building, Room 628, 50 Constitution Ave. NE, Washington, D.C.

HOW TO WATCH ONLINE: https://www.indian.senate.gov/hearings

Who Are Freedmen

During the early stages of colonization, members of five Southeastern tribes – the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek) and Seminole Nations – began enslaving Black people to build plantation wealth, just like the European American colonizers. That’s partly why the colonizers dubbed these nations the Five “Civilized” Tribes.

When the Five Tribes were forcibly removed from their homelands in the 1830s–40s, people enslaved by the tribes also made the long journey to Indian Territory. By 1861, between 8,000 and 10,000 Black people were enslaved throughout Indian Territory. In 1863 the Cherokee National Council passed an act freeing all people enslaved by their tribe, but many slaveholders ignored the law.

After the Civil War, new treaties between the U.S. government and the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole abolished slavery among the tribes and outlined citizenship rights available to the Freedmen and their descendants. These treaties were ratified in the summer of 1866.

The Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma is the only one of the Five Tribes to fully recognize and enroll Freedmen as citizens, a decision that came in 2017 following years of legal wrangling.

The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma considers Freedmen descendants as enrolled tribal citizens but does not extend them full rights. The Choctaw, Chickasaw and Muscogee (Creek) nations neither enroll nor formally recognize Freedmen descendants.