By THE OKLAHOMA EAGLE

George Jefferson, of The Jeffersons situation comedy fame, boldly claimed and wore his Black agency upon the shoulders of every small’ish suit jacket worn throughout his 11 seasons of television production. As I child of 70s, who’s world was defined by the newly evolving spectrum of Black representation on television, my brother and I learned that George’s Black agency empowered him to “tell it like it is”, “call a spade a spade” and “call out” Uncle Toms when they crossed his path. The latter target of his Black agency, Uncle Toms, earned a hotter fire of insult as he rightly believed that Toms represented the antithesis of Black progress, a betrayal of sorts to the Black community at-large. Toms had no place amongst the Black folk who were truly committed to our social, political, economic, and faith-oriented advancement. Toms, as brother George pointed out, bore false witness, harbored self-hating motives and possessed ill-intent. They (Uncle Toms) were quick to listen to our secrets then “run tell the man” about our plans. Toms were submissive, passive and would accept fate determined by their masters. Toms were skinfolk, but definitely not kinfolk. Toms were the bootlicking, cowardly scoundrels depicted by American author and abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe in the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin…. Right?

As with many longstanding myths, legends and folklore, their thinly-vailed deception slowly fads, and what remains is a newly discovered lie and the questions “How did we get here?” and “What have we done?” The former, certainly worthy of exploration, requires far more time and available editorial page space to explain than permitted. The latter, however, deserves our immediate attention.

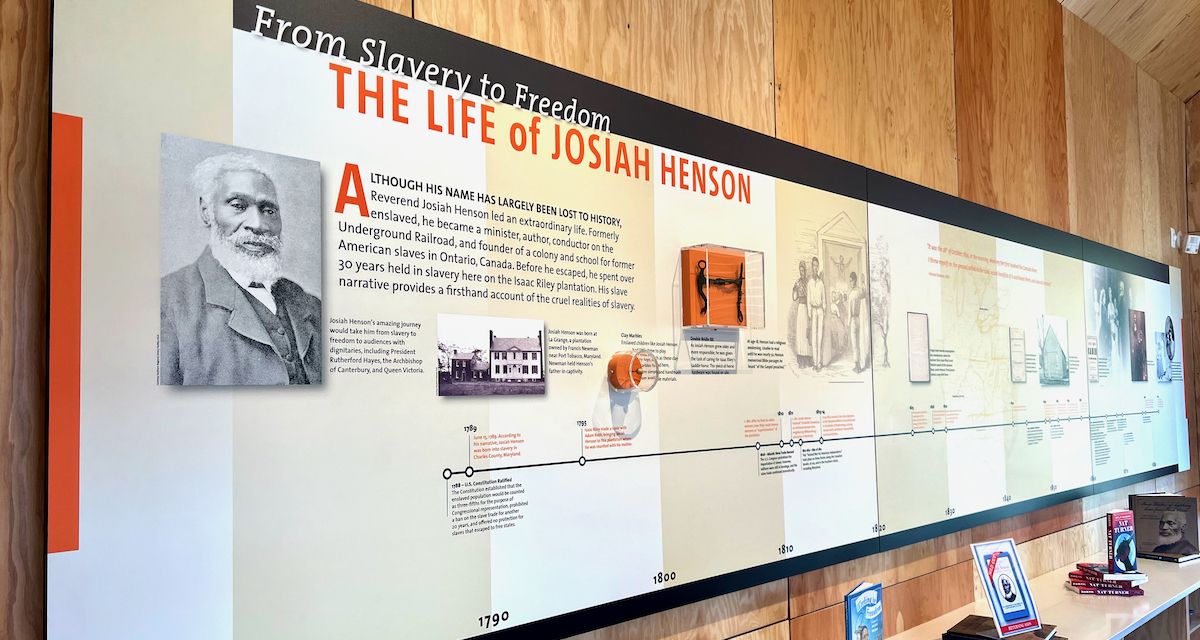

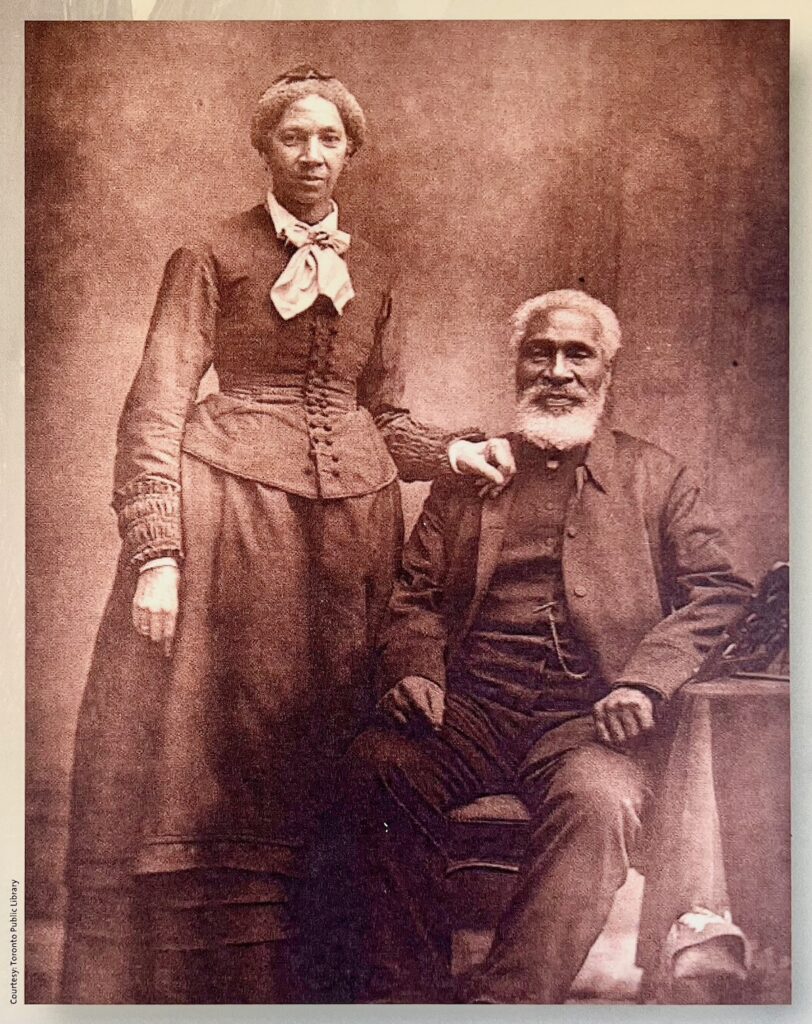

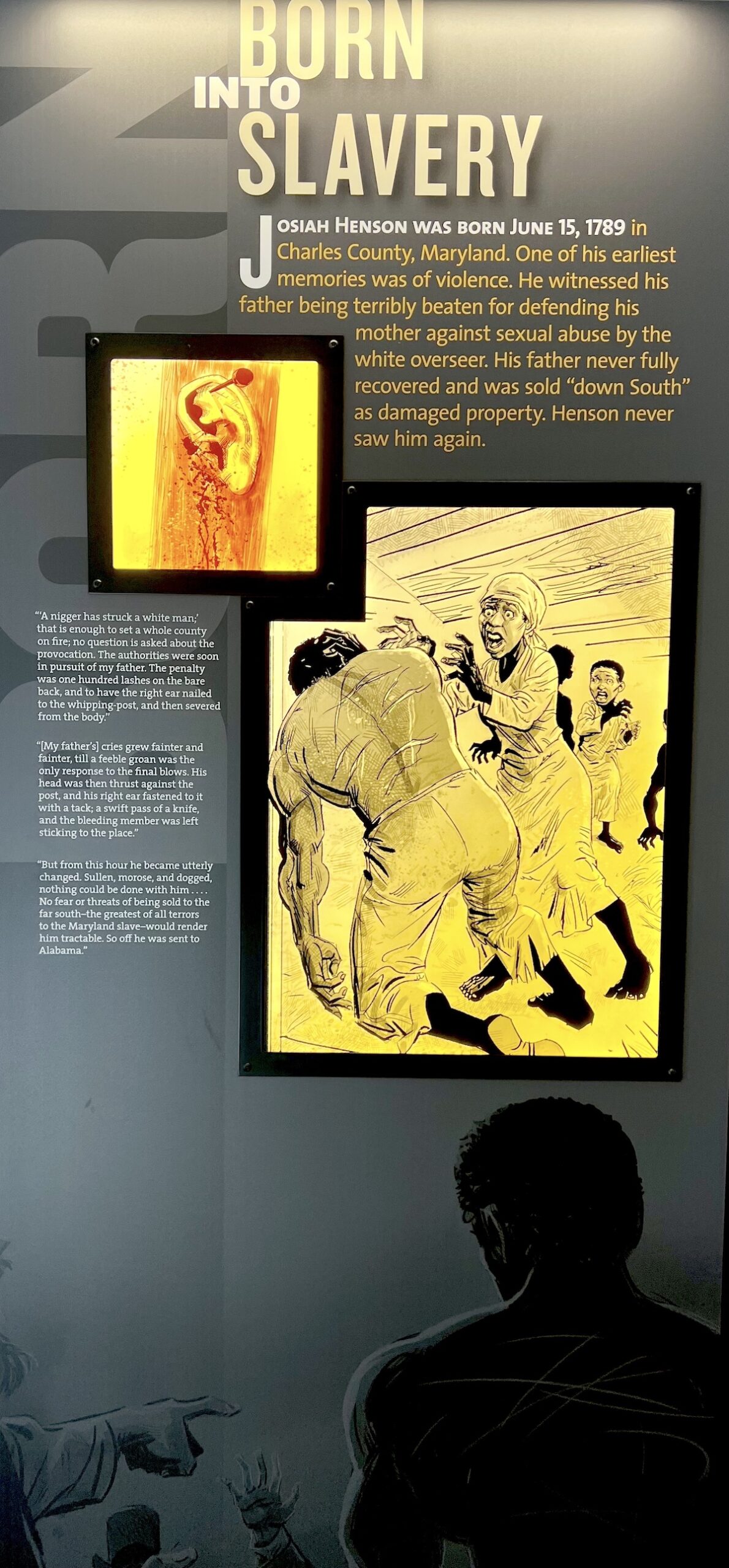

My brother and I were clear about the role of Toms, as children and young adults. We knew a Tom, when we saw a Tom. Our response to Toms varied little, as if our Black agency was well-informed by all that history could reveal about Toms. No book existed, upon the shelves of any library, that could adequately refute our reasoning. Years later, the unassailable truth regarding Uncle Tom was fully challenged and we found ourselves not only questioning what we’ve learned about such characters, but also how we weaponized the literary character. Inspired, in part, by the author’s reading of The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself (1849), Stowe published her two-volume novel in 1852. Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, earned such success as it has been regarded as the best-selling novel of the 19th century. Henson, similar to Uncle Tom, was a Black man of profound faith, a minister, abolitionist and author. Born on a farm near Port Tobacco, Charles County, Maryland, Henson’s back bore the same lash-derived scars as his father throughout a life of being sold as chattel. In 1825, the 36 year old enslaved Henson committed to assisting his master (Issac Riley) with preventing the loss of the Montgomery County, Maryland plantation due to economic hardship. His effort required the transport of eighteen enslaved Black men and women to a Kentucky plantation owned by Riley’s brother. Upon his return to Riley, in 1828, Henson attempted to secure his freedom with the offer of an immediate payment of $350 and a promissory note of $100. Riley, although Henson remained in servitude to him throughout the financial crisis, cheated the enslaved man by increasing the promissory obligation to $1,000 without Henson’s consent. The betrayal by Riley set in motion Henson’s planned, and ultimately successful, escape to Upper Canada (Ontario) with his family.

Uncle Tom, Stowe’s central character in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, like Henson, was an enslaved Black man, husband, father, and Christian, traded to plantation owners along the Mississippi River throughout the crest of his life. Stowe’s account of Uncle Tom’s life was a series of tragedies quite similar to the experiences of the more than 4 million enslaved Africans stripped of their native languages, faiths, and families, then savagely packed within the hulls of vessels for transport to The New World. His faith, centered within Christianity, was the underlying current that fueled his compassion for others and framed a character that would ultimately save the lives of Black children and families. Uncle Tom, we should be reminded, was denied the freedom experienced by Henson. Stowe’s account of Uncle Tom’s final moments were sadly tragic. In defiance of his masters’ (Simon Legree) orders to beat another enslaved man, Tom was viciously attacked. Legree, unsatisfied by his act of cruelty, resolved to crush the enslaved man’s faith in God. Although he suffered greatly after the beating, Tom assisted an enslaved Black mother and child to escape the plantation, then refused to reveal their location to Legree – resulting in a beating that would later prove fatal.

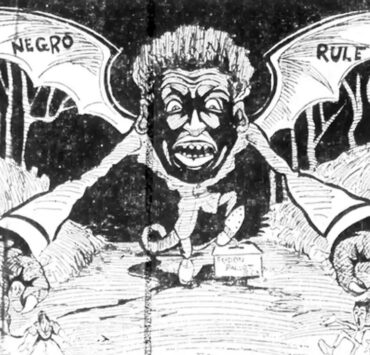

The caricature of the “black man all too eager to please whites around him”, as described by historian Henry Louis Gates in the introduction to “The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin” (Norton), was broadly rejected by Black Nationalists during the 1960s. Stokely Carmichael, in 1966, while denouncing N.A.A.C.P. executive director Roy Wilkins, cast the organization’s head as an “Uncle Tom”. A New York Times commentary titled Digging Through the Literary Anthropology of Stowe’s Uncle Tom (2006), noted Gates summation of Tom as a slave whose “very soul bled within him” for the wrongs he witnessed, had become “the most reviled figure in American literary history.” Gates’ opinion, it appears, evolved throughout the decades, focused less on the depiction of negative Black stereotypes, but instead the novel’s place in history. James Baldwin’s criticism of the novel, captured in “Everybody’s Protest Novel”, possessed little restraint, as he noted that Stowe’s work was simply a “very bad novel,” comprised of “self-righteous, virtuous sentimentality.” For his part, Malcolm X once framed Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as a “…20th century or modern Uncle Tom, or a religious Uncle Tom, who is doing the same thing today to keep Negroes defenseless…”

As is the case with brothers Baldwin, Gates, Carmichael, Malcolm, and many more, social consciousness should compel us to reveal truths suppressed by oppressive cultures and institutions, leaving no uncertainty of one’s disposition or opinion. Of equal importance, however, is our refusal to malign another Black man or woman with rhetoric informed by bias and poorly contextualized facts. Our children, today, must rely upon parents for a comprehensive and unbiased view of Stowe’s novel, without the burden of trending social critiques. As my brother and I learned, with the well-guided hand of our mother, the adoption and usage of racial epithets without consideration of their likely distorted history can figuratively wound those who are undeserving of such. Henson, like Tom, was not a Black man who quietly acquiesced to the whims and violence of his masters. The literary character (Tom) and man (Henson) were not merely servants to their god, but humble men who determined, on many occasions, that their humanity and faith would not be compromised by the evil harbored by lessor men.