By JOHN NEAL

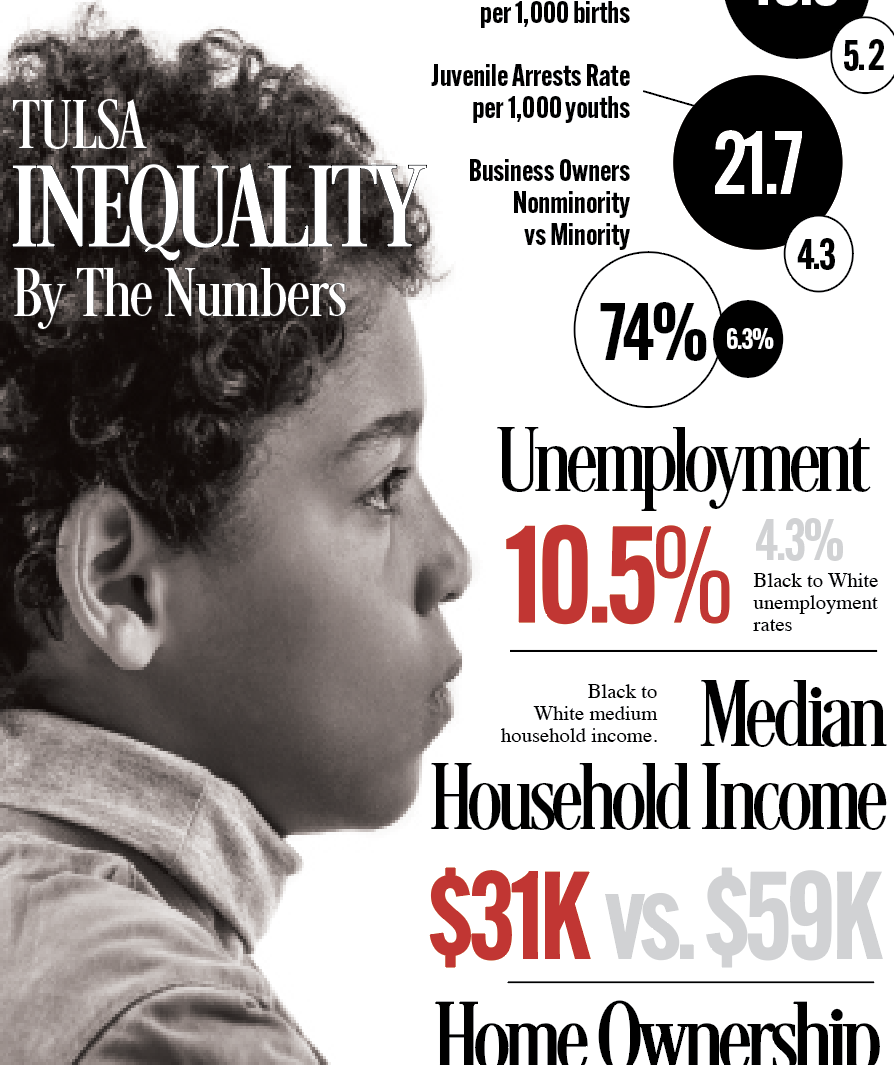

The city of Tulsa and the Community Service Council have released a report of “equality indicators” that depict bleak conditions for most Black Tulsans. The “Tulsa Equality Indicators Annual Report for 2021” shows Black Tulsans lagging in every measurement of wellbeing. The most startling areas of concern were the gap in income between Black and white households, the skyrocketing rates of infant mortality among Black Tulsans, and the poor record of criminal justice in the Black community.

“This is a huge issue,” said Kristi Williams, chair of the Greater Tulsa Area African American Affairs Commission and a well-known advocate for Tulsa’s Black community. ”These things need to be discussed and talked about more.”

A tool to advocate for change

Tulsa started issuing the indicators reports in 2018. They are designed to take stock of economic and social outcomes based primarily on race, gender, income, and geography in the city using 54 indicators. City officials call the process, “Measuring change toward greater equality in Tulsa.”

The Oklahoma Eagle examined the report the focuses primarily on the aspects of its findings concern racial demographics. Tulsa is only one of six U.S. cities that use a comprehensive measurement tool and methodology template created by the City University of New York to gather this valuable data.

The “report has become a tool that Tulsans from every sector and part of the city use to advocate for change, focus resources, and drive decision making,” Mayor G.T. Bynum said in a letter issued with the release of the 2021 report.

The 23-member African American Affairs Commission held a meeting to review the report. Williams said she used the meeting to push the city to find solutions to the problems outlined in the report.

“There’s a problem,” she said during the presentation. “There are things we are going to have to find solutions for ourselves and push them through the city and different organizations.”

She added, “What’s the use of measuring things if we aren’t going to do anything about it.”

Krystal Reyes, the city of Tulsa’s chief resilience officer, said she would work with and support the Commission in determining “what to focus on and where we have gaps.”

The biggest gaps

In the “Economic Opportunity” section, the report states, median household income for White Tulsans is almost double that of Black Tulsans. Black household income in Tulsa is $30,000. The ratio of Black to white income is 1.91 in Tulsa, compared to 1.55 nationwide. The status of Black ownership of businesses and unemployment were even worse. Black business ownership was less than half that of Asian Americans. Unemployment for Blacks neared two and a half times the rate for whites.

Worst still was the heavy concentration of payday centers in North Tulsa, where many Black people live. That reflects an effort to exploit North Tulsans with lower incomes and higher unemployment. A scarcity of banks or credit unions on the Northside, coupled with the significant presence of payday lenders, gave Tulsa the worst equality rating possible in this category: a score of 1 on a scale of 1 to 100.

Alarming mortality data

“What indicators really stick out to you and scream we got to do something about that?” That was the pointed, spot-on question that Gregory Robinson, Vice Chair of the Commission, asked Reyes during the meeting.

Reyes responded by echoing a concern raised by Williams about the “skyrocketing” infant mortality. “It is one of the main indicators of how healthy a community is,” she said.

The report revealed Black infant mortality is almost 17 per 1,000 births, while white rates are at the national average of between 5 and 6 per 1,000 births. The infant mortality rate for Black Tulsans is far above the average rate of 10.8 for Blacks nationwide. This finding, coupled with higher rates of cardiovascular disease among Blacks and lower life expectancy following retirement, contributed to a meager score on “Mortality” equity.

Housing inequities

Homeownership garnered an even lower rating. Black homeownership was half that of whites. The report’s finding of a 30 percent ownership among Blacks is also ten percentage points below the national average. Nationally 42 percent of Blacks are homeowners. Housing complaints were much more frequent in North Tulsa, and citywide home evictions were 40 percent more likely. And 70 percent of those residing in North Tulsa live in what the report calls a “food desert,” roughly referring to scenarios in which residents are a mile or more away from a supermarket or grocery store. This indicator also garnered the lowest score possible. The “food desert” is particularly problematic when “Black households are twice as likely as white households not to have access to a vehicle.”

Poor Criminal Justice Performance

The ratings on criminal justice were by far the lowest of any of the significant areas examined. Justice ratings have been steadily declining since the first report was issued in 2018. The lack of social equity in arrest rates was stark. A Black adult was three times more likely to get arrested than a white counterpart, while youth arrest rates for Blacks were five times higher than whites. Thus, Black youths, while representing only 15 percent of the youth population, were subjected to almost fifty percent of youth arrests. The report did not compare officer use of force rates to whites. But it concluded that “Black Tulsans are nearly five times more likely to experience officer use of force than Hispanic/Latino Tulsans.”

The child abuse and neglect rate in Tulsa County are near twice the national average. Tulsa Black residents are also almost four times more likely to be homicide victims than whites, contributing to a marked decline in the “Safety and Violence” dimension.

The report notes what has long been a sobering reality for African Americans in Tulsa and nationwide. It noted: “Extensive research finds that African Americans experience disproportionate levels of policing, stops, searches, issuing of citations, use of force, convictions, sentencing severity, use of alternatives to incarceration, arrests for failure to pay fines and fees, and youth sentenced as adults, not just in Tulsa but across the nation, that do not align with higher levels or severity of crime committed. Systemic racism and implicit bias throughout the entire criminal justice system have been found to significantly contribute to these disproportionate levels.”

Overall findings

In the aggregate, Tulsa had an overall score of 39.2. The scale ranges from 0 to 100, with 100 representing equality. This year’s score was slightly below the average for the last four years and not a good score if equality is the goal. And, if the comparative scores are aggregated for Blacks, particularly those residing in North Tulsa, the inequality is far greater than the score indicates. Additionally, very few indicators compared Tulsa to national averages. But The Oklahoma Eagle’s comparative research shows Tulsa lagging the nation in racial equity ratios to whites for unemployment, household income, homeownership, and most notably, infant mortality, etc. The consistently poor and declining internal ratings in the criminal justice system, particularly for Blacks, should be a grave concern.

The city’s response

Realizing that Equality Indicators remained stubbornly immobile or, in some cases, in decline, Tulsa took a significant step forward in 2021, according to Mayor Bynum. “For six months, we held in-depth community conversations… to address disparities throughout Tulsa.” These community conversations resulted in a Data for Action Resource Guide and Learning Series. The guide highlights “the many programs, services, and policies that are taking place in Tulsa to address disparities found in the Equality Indicators data.” Ms. Reyes, in an interview with the Oklahoma Eagle, said “four years is not enough time” to make meaningful progress, but “we don’t want the report to just sit on a shelf.” More information on both the Equalities Indicators and Data for Action plan can be found here: https://csctulsa.org.tulsaei/

Commissioner Williams, who participated in some city-organized community meetings, remained skeptical. She told the Oklahoma Eagle: “This city has a way of looking like they’re doing something when they aren’t doing anything.” She added that the city “had no solidified plans for solutions.” As a result, the Commission is scheduling a retreat where they expect to make plans to address these problems.