I remember when I first admitted to myself that I was an alcoholic. One of the main reasons I decided to get help was that I wanted my mother and father to see their son sober again before they left this earth.

That was in July 2006.

But when my father passed in 2018 at the age of 95, I honestly thought it would be too much for me to handle. I was so afraid that I would fall off the wagon. Take the easy way out when trying to cope.

And I almost did.

I almost slipped.

When you’re an alcoholic, it’s times like those that test you the most. When you’re seeking comfort. When you’re confused or in pain. When the s*** hits the fan.

When you’re an alcoholic, it’s times like those that test you the most.And that’s where we are right now as a society. As a country. As a world.

The s*** has definitely hit the fan.

And it’s such a strange and difficult time because now, while this COVID-19 pandemic has forced us to isolate ourselves, what we really need more than anything is each other. To feel whole again. To feel normal again.

Or just to know that we’re not alone.

That’s why I’m writing this today. Because there’s a particular community of people who I know need each other now more than ever. A community I’m proud to say I’m a part of.

Alcoholics Anonymous.

There was no one thing. No come-to-Jesus moment, no one big mistake or drunken episode that put me over the top and caused me to finally admit to myself that I was an alcoholic.

It was years of waking up in the middle of the night, unable to remember how I got home … walking downstairs and cracking the garage door open to see if my car was there.

It was years of waking up in the morning and seeing my wife crying, which let me know that I had f***ed up the night before.

And it was years of drinking before each visit to my parents’ house because my father’s memory was deteriorating — he would tell the same stories over and over again — and it was difficult to watch.

It was all those things.

And even after I admitted to myself that I was an alcoholic, it was even more difficult to admit that I actually needed help. Because I had dealt with this sort of thing on my own before, back in the ’80s.

With cocaine.

It was 1982 and I had just retired from boxing (for the first of many times), and I was riding this wave of popularity and prosperity created by my boxing career. I had shaken hands with presidents. Played golf with movie stars. Partied with celebrities in Vegas and all over the world. Life was big. Life was animated — at times, exaggerated. Life was whatever I wanted it to be. And when you live a big life like that — when you can buy whatever you want without even looking at the price tag and everywhere you go people know you and shower you with praise — it can be hypnotizing.

I was hypnotized.

In the early ’80s, cocaine was a part of that big lifestyle. It was many people’s drug of choice. So I tried it, and I liked it. I used it when I felt bad — when I missed the exhilaration of competing at the highest level in the ring, which was often. It helped fill the void boxing had left in my life. So it became my drug of choice, too.

And it nearly destroyed me.

The people I partied with loved it. But my family and the people who truly cared about me? They didn’t even want to be around me, because I wasn’t myself. I was not Ray — at least not the Ray they knew. I was this inflated, exaggerated version of Sugar Ray that they didn’t even recognize.

It wasn’t until I decided to make my boxing comeback that I finally stopped using cocaine. I fought Kevin Howard in 1984 and stopped using while training for that fight. Afterward, I retired again and went right back to cocaine — back to that big life. But a couple of years later, when I came back to fight Marvin Hagler, I stopped using cocaine for an entire year to prepare myself.

I won that fight.

And I never used cocaine again.

I can honestly say that if I had stayed retired that first time, I wouldn’t be here, writing this. Cocaine would have been the end of me.

My father used to drink. Heavily. And one day he just stopped. He smoked cigarettes, and he quit that, too. Cold turkey. I had done the same with cocaine. So a part of me believed that I didn’t have an addictive personality. That if I ever wanted to quit something, I could, no problem. Because my father had done it, and I had done it, too. It must have been in my genes.

But when I admitted to myself that I was an alcoholic, it was different than quitting cocaine in the ’80s. Because this time … I didn’t have boxing to go back to.

In the years after retiring for good in 1997, I didn’t realize that I was using alcohol to cope with the void boxing had left in my life. I wasn’t living that big life anymore. My whole world had changed. And in this new world of mine, I drank as often as I could. I would take four shots before even going out at night. At one point, I switched my drink of choice to vodka because the smell wasn’t so easily detected.

I didn’t drink to socialize.

I drank to get drunk.

I drank to escape.

I wanted time to stop.

I wanted the world to go away.

People ask me how I could feel that way — how, with all the money and success and fame I had accumulated in my life, I could be so unhappy. And the only way I can answer that is to say that … there are two Rays. There’s Ray Leonard — the one my mother and father raised, the one my wife married — and there’s Sugar Ray. And when my boxing career ended for good and that big life went away, I started to feel like all that love and praise and attention I got wasn’t for me at all. That was for Sugar Ray. I felt like people had loved me for what I had accomplished, not for who I truly was.

People who know me best — especially my wife — would tell me otherwise. But it was hard for me to really internalize that.

I guess you could say that’s what drove me in 2006 to finally admit that I was an alcoholic: I finally listened to the people who truly love me, and I really understood that they loved me for who I was, not for what I had accomplished in the boxing ring.

But admitting that I was an alcoholic was only one part of the process. The second and more crucial part was seeking and accepting help.

But I had never run away from a fight.

And I wasn’t about to start.

I remember my first AA meeting. My wife dropped me off. I walked into this small, dark room somewhere in Los Angeles. And honestly? I was scared. I had stepped into the ring against some of the greatest fighters in history — Roberto Duran, Tommy Hearns, Marvin Hagler — and I had never been more scared in my life than I was when I walked into that AA meeting room.

I walked in and sat in the back by myself, right next to the door. I had sunglasses on and a baseball cap pulled down, hiding as much of my face as possible as I listened to the people up front speak, one by one.

“My name’s Bob, and I’m an alcoholic.”

“My name’s Sarah, and I’m an alcoholic.”

Around the room they went: name, followed by alcoholic.

Then everybody turned in their seats to look at me.

Some of them stared. Hard. One person actually squinted and said, “Hey, aren’t you…?”

I glanced up and shook my head.

“My name’s Ray Leonard,” I said.

I did not follow it with alcoholic.

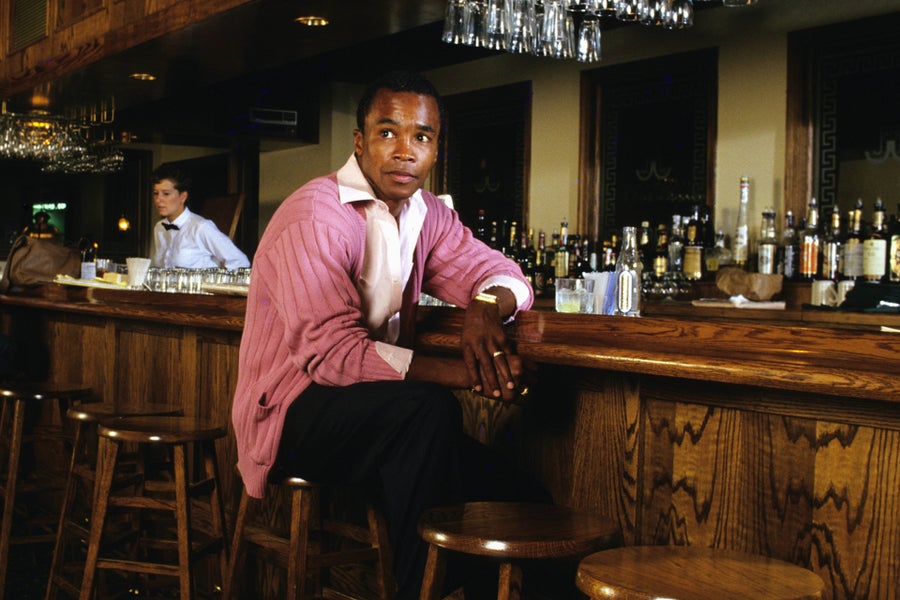

Bettmann/Getty Images

From way up front, the group leader said, “Welcome, Ray. But you only have to say your first name.”

I nodded, and they went on with the meeting while I sat in the back and listened.

It went that way for a few months. I continued to attend meetings, but even though I had admitted to myself that I was an alcoholic, I just couldn’t bring myself to say it out loud because … I’m Sugar Ray Leonard. Hall of Famer. Six-time world champ. Olympic gold medalist. I didn’t want to believe that I was anything other than that. And I didn’t want anybody else to believe it, either.

Then, one day, they went around the room again like usual, and when they all turned to me in the back, I was finally able to say it — to myself, and to the rest of the world.

“My name is Ray,” I said.

“And I’m an alcoholic.”

Before every one of my professional fights, before walking out to the ring, I would stop and look in the mirror. I’d look myself in the eyes. And if I saw Sugar Ray staring back at me, I knew I was going to be O.K. But if I saw Ray Leonard, the civilian? It was going to be a tough night.

Ninety-nine percent of the time, I saw Sugar Ray.

I haven’t stepped into a boxing ring in 23 years. But I still fight every day. And there are millions of Americans who are fighting the same fight against alcoholism or addiction. People who look in the mirror each day and have to ask themselves what they see. Is it someone who is strong enough to maintain their sobriety during these uncertain times?

To those people, I want to say two things.

First: Yes, you are strong enough.

And second: You are not fighting alone.

COVID-19 is impacting all of us in so many ways. We are all coping with the isolation, but many are also facing financial distress. Maybe you’ve lost your job — or worse, a loved one — during this pandemic. The effects are far-reaching. We’re all feeling them in different ways.

And it’s times like these when what we really need more than anything is each other.

When my father passed away, I almost fell off the wagon. But I didn’t. And it’s because of the support I had from the AA community and from my sponsor. Attending in-person AA meetings has been a huge part of my life and well-being for the last 14 years. Now, though, that’s been taken away from me, like it has been for so many others.

So these days I attend group meetings online via videoconference.

There were days when this whole stay-at-home thing started when I didn’t utilize these online meetings. I would just get up and play tennis or whatever and try to go about my day, and … I don’t know. I just wasn’t myself. I noticed it. My wife noticed, too. She’d tell me point blank, “You need your AA.” It’s like a meditation for me. It starts my morning off the right way, so I can stay centered and stay sober, even in the midst of everything going on in the world. Because sometimes, it’s just about talking. Connecting. Knowing that there is support out there for you.

Honestly, I’m just doing the same thing everybody else is doing right now, which is … the best I can.

My AA is a huge part of that.

I’m just doing the same thing everybody else is doing right now, which is … the best I can.It hasn’t been easy. I’ll admit that. It takes work. It takes courage. And above all else, it takes humility.

Just like it did when I went to my first meeting 14 years ago.

So if you’re missing your in-person meetings and you haven’t utilized AA online yet, I urge you to do that. It’s there for you.

WE are there for you.

And if you’re not a part of the AA community and know somebody who is — or if you know anybody who is struggling with alcoholism or addiction — please reach out to them. Let them know that everything is going to be O.K. Let them know that we’re in this together. All of us.

Let them know that even in the most uncertain of times — even in isolation — they don’t have to be alone.

God bless.