By DAVID ARNETT

Editor’s note: This article is reprinted from the March, 1993 Union Boundary. The author currently publishes www.TulsaToday.com

Some traces of a historic community remain near the northeast quadrant of 51st Street near Mingo Road, but the disappearance of a park sign naming the town does not surprise most former residents of Alsuma, Oklahoma. The pre-statehood community between Tulsa and Broken Arrow has all but disappeared.

In 1905 the first post office opened with the name Welcome, Oklahoma. The next year the 165-acre town site name was changed to Alsuma and a post office operated there until 1926 when independent service was discontinued.

According to long-time Alsuma resident DeEtta Perryman Gray, the town was taken from the first two words of three names: Alice, Susan and Mable. Grey did not know who the girls were or why the names were used together.

Although most press reports of the day refer to Alsuma as a black community, the town had both black and white residents. The focal point of the community was the KATY Railroad Station, according to Gray. Records show the passenger railroad station opened in 1909 and closed in 1940. A second station was opened in1943 and retired in 1971.

Edward L. Goodwin, Jr., co-publisher of the Oklahoma Eagle, was raised across the street from Alsuma and remembers “it was just like most other towns then. The railroad split the community in half, so that the blacks lived on one side and the whites lived on the other side.”

Black families were the first owners of record for much of the land in east and southeast Tulsa. Black slaves traveled with the tribes as they were relocated to Indian Territory and, after the Civil War, were freed. Those former black slaves became official tribal members with most receiving land allotments of 40 to 160 acres.

Most of the men worked as farm and ranch hands in the early days. Over the years, Alsuma grew to a population of around 75 families. Tulsa annexed Alsuma in 1966, but few, if any, city services were provided. The residents were also forbidden to build septic tanks by the City-County Health Department. The department claimed the clay soil stymied efforts to build modern sewer systems and declared a moratorium on area building in the late 1960s. The city approved the redevelopment of Alsuma by Urban Renewal as an industrial park in 1969 and rezoned the entire “poverty pocket” as industrial property in 1970. After most Alsuma residents tired of fighting officials and moved, Tulsa extended the sewer in 1971.

Edward L. Goodwin, Sr. and his wife Jeanne B. Goodman bought 160 acres for $16,000 and built a beautiful native stone home in the late 1940s across 51st St. from Alsuma. Jeanne Goodwin said, “We went to church in Alsuma and really enjoyed the people of the community. In my husband’s third career, he operated a five-pond fishing facility on the property until the early 1980s when we sold the land.”

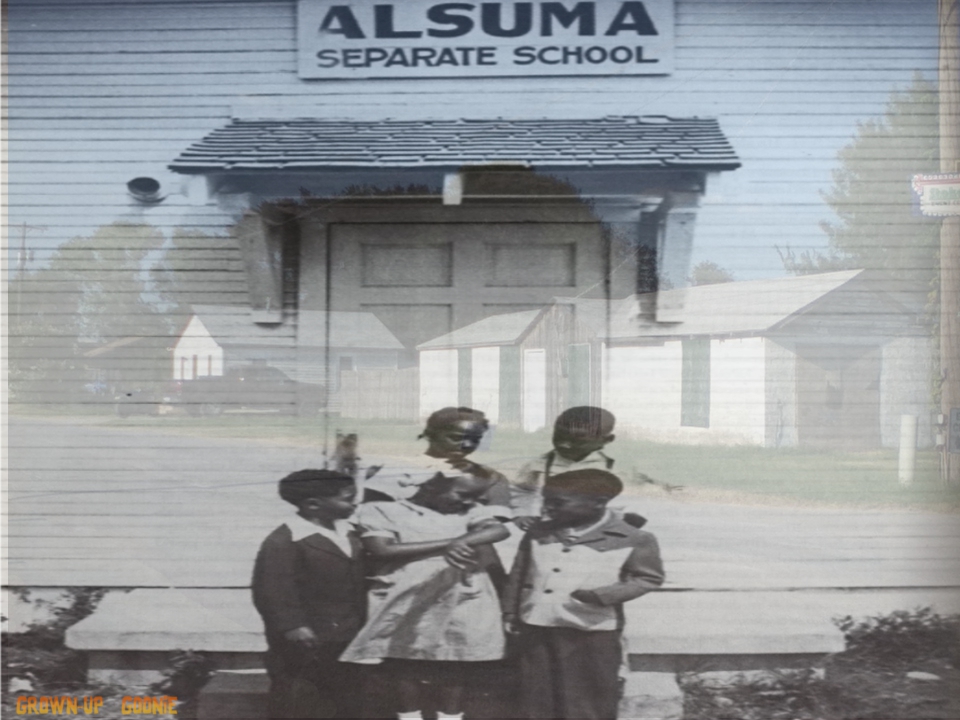

A lifelong Tulsa area teacher, Jeanne Goodwin taught at the Alsuma Separate School until integration was ordered in 1955. “It was my first experience with separate, but unequal schools. I was raised in Illinois in an integrated system,” she said. “The Alsuma parents were truly involved in their children’s education and that made a great difference.”

Her daughter, Jeanne Goodwin Arradondo, a 1960 graduate of Union High School now residing in Houston, remembers the segregated Alsuma School as being far inferior to the Union school on 61st Street She says, “Alsuma didn’t have running water or bathrooms, but most of the students were successful later because of the hard work of the teachers, especially my mother.”

The Goodwin’s sent their children to Union School after integration in 1955. The elder Goodwin says, “Our daughter Jeanne was Vice President of the Student Council. Daughter Carlie (class of 1962) was a top student and Class Treasurer. I still remember when our son, Bob, went with a group of Union students to Dutches Party Barn (a popular swimming and recreation center for teens at the time), and the management wouldn’t let him in because he was black. The whole group of white kids turned around and went somewhere else for a sandwich rather than let a fellow student be excluded,” Goodwin said.

Alsuma Park was established at Goodwin family’s urging and was dedicated to the lifetime work of Mrs. Goodwin who said, “At that time, black children couldn’t play in Tulsa parks. Alsuma kids would come down and play on our land, but we wanted something more for them.”

While still on the current Tulsa Park and Recreation Department Park Inventory and Facilities Compendium, Alsuma Park, 9801 E. 51st St., is primarily a Stormwater Management facility today. There are five soccer fields in the sunken detention pond area, but the one playground unit listed could not be found. Apparently, it disappeared along with the park sign.