July 4th celebrations remind some Black Americans of America’s sordid racial past.

ON JUNE 4, 1776, THE Declaration of Independence was signed, marking the colonists’ independence from Great Britain. But some 75 years later, some black Americans weren’t ready to celebrate.

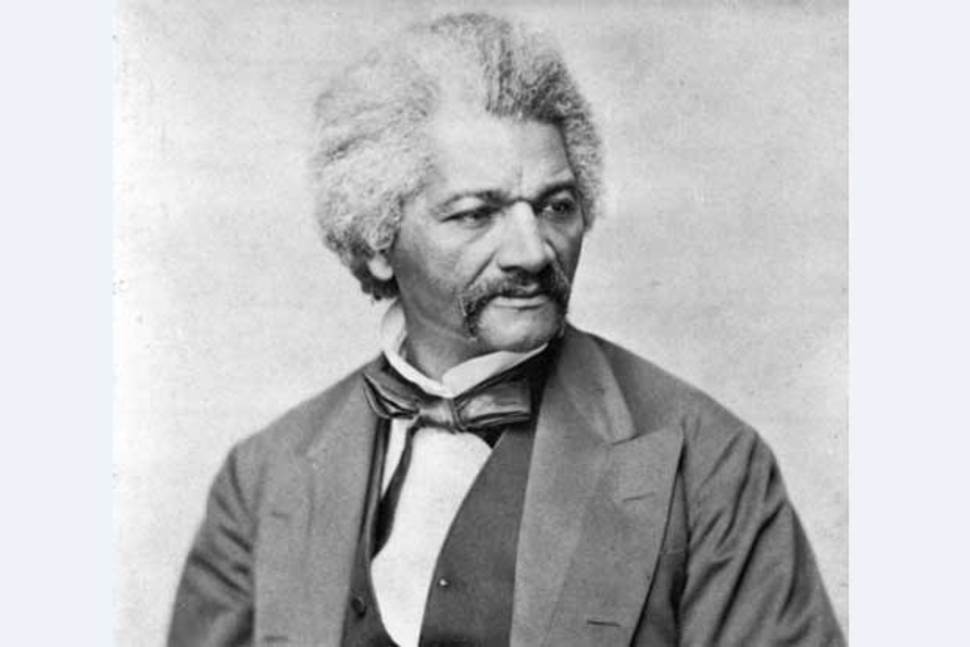

Abolitionist movement leader Frederick Douglass gave a scathing speech the day after Independence Day in 1852, saying: “This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn…. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day?”

Douglass reminded listeners that when the Declaration of Independence was signed, many blacks were still slaves. Even the British were more likely to offer freedom to blacks than the colonists.

Fast forward to today where many Black Americans still remember Douglass’s sentiments.

As one reader of Politico’s Playbook writes in to reporter Mike Allen Thursday: “Independence Day is odd for black people. Today, America is a better bet for everybody, but in 1776 most blacks would have sided with the Brits (and many did).”

Chris Rock made his feelings known more plainly. Hours before celebratory fireworks went off across the nation in 2012, the comedian wrote on Twitter:

Complicated or not, some black Americans find reason to celebrate the holiday.

In a Washington Times’ op-ed, Stacy Swimp notes that at least 5,000 black men fought for the Continental Army against the British, men who believed that freedom from Britain would ultimately result in their freedom from slavery. Swimp also names Black founding fathers he believes should be remembered on the 4th, like Crispus Attucks, Peter Salem, and Salem Poor.

And he points out that while slaves weren’t free at the time of the declaration, it is as a result of that document that every American, under the U.S. Constitution, is equally guaranteed individual freedom.

“What, to Black Americans, is the 4th of July?” he writes. “Everything.”