By S.L. Price

Late one late March afternoon NBA player agent Rich Paul, 38, whose professional manner swings between stone-faced cool and startling focus, is chewing through his third tangerine and detailing how he’s been singled out as the reason that two franchises, the league at large, and—why not?—American sports are going straight to hell when something reminds him of his childhood friend Squirrel. “An unbelievable kid, killed for no reason,” Paul says. And for the first time in three hours of talking, his bearing breaks.

“His girlfriend loved him so much, you know what she did?” he says, voice rising as he recalls the brutal last seconds of 18-year-old Starr Hudson and Kenneth Johnson, 21. Now Paul is up behind his desk and standing, transported 18 years and 2,053 miles, from Los Angeles to the battered east Cleveland neighborhood of Glenville: Legs spread, right hand firing at the floor with an imaginary gun. “When the guy was standing over on top of him, shooting him like this, she got on top of him. Guy killed them both. They buried them together. That’s the type of s— that I’ve been through.

“So: All . . . this?” His arm describes a wide arc meant to encompass today’s galaxy of panelists, pundits, vulturous rivals, flummoxed general managers, hoops bloggers: the whole whispery, shouty basketball-industrial complex. “What are we talking about? Do you understand what I just said? She laid on top of him to die with him. That type of s—, that is what’s important to me. I come from a place where there was no way out. How do you get out of there? How do you go from the ’hood to Hollywood? You don’t, right? So the discredit, the disrespect is the one thing I’m not going to tolerate.”

He sits and—just like that—balance is restored. Glenville dissolves, and Paul is again ensconced in the sunny upstairs office in one of those boxy modern L.A. homes (small pool, smaller yard) that you’d call “cute” until hearing that it went for $3 million in 2016. Paul lived here sparingly until last summer, when he spent $4.35 million for another, bigger house nearby and began converting his first buy into the western beachhead for his Klutch Sports Group. Soon after, Anthony Davis, the Pelicans’ all-world big man, fired his agent and hired Klutch, which, though hardly the richest or biggest agency handling NBA talent, has become the most discussed, admired, loathed, ridiculed, daring and feared operation in the business.

Of course, buzz has been a Rich Paul constant since 2012, when he—along with bestie LeBron James—rattled the league’s power structure by bolting Creative Artists Agency and establishing Klutch. It was easy, at first, to dismiss him as a King James tool, yet each new client (Eric Bledsoe, John Wall, Ben Simmons and now 25 others) and brokered contract ($624.8 million and counting) increased Paul’s clout. And nothing signaled Klutch’s raw challenge to the status quo more than last January, when Davis told New Orleans not only that he wouldn’t sign a five-year, $240 million super-max extension with the team this summer, but also that, with a year-and-a-half left on his contract, he wanted to be traded—and Paul made the demand public.

![]()

Coming just 10 days before the trade deadline, with prime Davis suitor Boston sidelined by complex contract rules until summer, the maneuver walked and quacked like a demand to send Davis to the rudderless Lakers and, more to the point, James’s desperately welcoming embrace. It was also seen as one of the most naked power moves in recent memory. “We cannot,” Charles Barkley said on TNT, “have players and agents colluding to stack super teams.”

Paul’s Who? Me? protestations aren’t very convincing and, in truth, he doesn’t try that hard. He claims no control over L.A.’s personnel decisions and takes umbrage at the suggestion that he’d send Davis—still, for the moment, a Pelican—into a less than ideal situation to help the man who changed his life and made him rich.

“Did you say that to David Falk? Would you say that to Arn Tellem?” Paul says of two agents who juggled vast stables of clients without charges of conflict of interest. “You’re only saying that because you feel like, ‘Well, Rich wouldn’t be in this position without LeBron,’ right? My thing is: Take LeBron off the Lakers. Are the Lakers not a great destination for an arguably top-two player that went to Kentucky and won a national championship, signed with Nike? For a team that’s had centers from George Mikan to Wilt Chamberlain to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar to Shaq?

“So now, when you add LeBron, that’s what? The cherry on top. LeBron’s 34 years old. Anthony Davis is 26. So when LeBron’s done playing, the Anthony Davis trade is still rolling. What better place to do it than L.A.? If it was L.A.—I never said ‘L.A.’ But there’s no negative to that. Who gives a s— what you’re talking about, about me trying to help LeBron out? No, I’m not. I’m trying to help Anthony Davis. Now, if helping Anthony Davis helps LeBron in the long run? So be it. But my goal is Anthony Davis.”

He veers off to speak of the Knicks as an equally alluring destination for AD. “The only difference is, they don’t have as many championships as the Lakers,” Paul says. “They got a tradition. It’s a big market—not that it’s only big markets. They have cap space, flexibility, they’re able to absorb more than one star. What’s wrong with that?”

The Pelicans? Even though New Orleans landed the No. 1 pick, presumably Duke forward Zion Williamson, in the 2019 draft lottery, and even though its new general manager, David Griffin, is trying valiantly to change Davis’s mind, every report and hint still has AD standing by his demand.

Boston? Davis’s father told ESPN in February that he wouldn’t want his son playing for the Celtics, and Paul confirms that he has warned off Boston management.

“They can trade for him, but it’ll be for one year,” Paul says. “I mean: If the Celtics traded for Anthony Davis, we would go there and we would abide by our contractual [obligations] and we would go into free agency in 2020. I’ve stated that to them. But in the event that he decides to walk away and you give away assets? Don’t blame Rich Paul.”

Posturing? Maybe. But get ready for another year of it, because Paul says Davis won’t be signing an extension anywhere this summer.

“Where he’s going to land? I have no idea,” Paul says. “And it don’t matter. We’re going into free agency. Why does it matter to me where he goes? Earth: We’re going into free agency. He has a year, he has to play. But after that, I can’t say it no bigger: WE ARE GOING INTO FREE AGENCY. 2020: ANTHONY DAVIS WILL BE IN FREE AGENCY.”

Of course it matters: Whatever team Davis plays for next season will be able to offer him more money to stay than any of his other suitors. And though reports have Pelicans owner Gayle Benson loath to do the Lakers any favors, and though many believe L.A. lacks the deftness to pry Davis away, the spin that he would be ill-served playing in purple-and-gold won’t let Paul alone.

“See, everybody wants to fabricate the facts when it’s me,” Paul says. “That’s just like saying, ‘No, A-Rod, don’t marry J-Lo. Are you out of your f—in’ mind, man?’ This is Jennifer Lopez! I mean, who would you rather me marry? The Lakers are Jennifer Lopez. You don’t want me to date Jennifer Lopez? Give me a reason I shouldn’t date J-Lo!”

Funny, no? It’s a kick to hear a deadpan Paul riffing outrage, and important to note that he’s good company. For all the high stakes, agentry is at base a service job, and Paul came to it with none of the usual credentials—no law, business or even undergrad degree. Even by non-NBA standards, he’s hardly imposing, with slim shoulders and smallish hands (“I’m 5’8″,” Paul says. He seems more 5’6″. “Come on: 5’6″? That’s f—–’ ri-DIC-ulous.”)

But it’s striking how many who have come into Paul’s orbit, even those critical, offer testaments to his “social talent” or niceness—echoing James’s first impression of hearing “humbleness and generosity” in the tone of Paul’s voice. No one doubts that he can be ruthless and calculating. But he does so while posing question after question, never fronting an expertise he doesn’t possess, and giving the impression that he’ll always tell his truth.

“Rich is a good listener, has humility, has worked as much as anyone trying to learn and, most important, he’s sincere and has an empathy,” says Tellem, Davis’s first agent and, until he took over as Pistons vice chairman in 2015, one of the most accomplished player reps in league history. “So he connects and understands what his clients are trying to achieve. He builds incredible personal relationships, and they believe in him. That’s the essence of a good agent.”

But as the prime facilitator of all things LeBron—whose unprecedented forays into roster assembly, franchise-hopping, and TV and film production have expanded the bounds for an elite athlete beyond recognition—Paul’s every move bristles with a uniquely cutting edge. He has become the go-to agent for the aggressively restless player. “When I’m done [playing] and I’m not around the media every day, I hope that somebody’s continuing to fight off the narrative: You’re the athlete? Can’t have power, and can’t be in control,” James says. “Because you can.”

Money used to be the primary marker of that power, but with the advent of the rookie wage scale in 1996 and ensuing restrictions on max salaries, the expression of clout—and of an agent’s skill—shifted.

“That changed the perspective,” Tellem says. “If the salaries are roughly similar, what can a player control? It’s no longer financial. Where he has his say, then, where he has some control, is in the choice of where he plays and with whom he plays.”

Keep in mind: Agents have long meddled in team affairs. Tellem single-handedly steered Kobe Bryant to the Lakers in 1996, and Falk essentially brokered the 12-player, four-team deal in 2000 that sent Patrick Ewing from New York to Seattle. But with a LeBron-led trend toward shorter contracts now making “pre-agency” speculation a year-round staple, the league seems awash in grass-is-greener syndrome. Or, perhaps, it’s just that top-line talent is capitalizing on increased leverage.

“Other players are seeing the power, influence and control that a great player like James has over an organization, and are striving for that same control, power and influence,” says ESPN commentator and former coach Jeff Van Gundy. “It’s the next level. And now you have to ask yourself, which I always do on these questions, What’s next?”

Still, Davis’s move—with its timing and immediate focus on one destination, and apparent disregard for the shattering effect on two locker rooms—seemed an iteration of player empowerment that few saw coming. You couldn’t get two sentences into an NBA chat, live or virtual, without hearing terms like debacle or carnage, and while the Lakers and James drew heat, and Davis’s good-guy rep evaporated, no one took more flak than Paul. The failure of any deal to materialize by the Feb. 7 trade deadline read like the ultimate humiliation.

But it’s strange. Walk into Paul’s office, and there’s no sign of panic or even that hopped-up alertness you sometimes see in those parked briefly in the glare of public attention: Good or bad, just spell the name right! No, when first asked about the blowback from the AD trade gambit, Paul glances up slowly from his phone, blinking, and says, “For who? Not me.”

At first, that feels out-loud laughable. The NBA joined in the tsk-tsking by docking Davis $50,000 for breaking its rule against public trade demands. Fallout spread leaguewide: On Feb. 5, Lakers forward Brandon Ingram hit two free throws as an Indiana crowd chanted, “LeBron’s gonna trade you!”

Paul admits the situation got out of hand. (“Would I have wanted things to be handled a bit better? Absolutely.”) But he goes on to dump all blame on then Pels GM, Dell Demps. Because Paul insists his plan wasn’t to go public. He says that he first informed Demps on Jan. 25 of Davis’s intentions, and Demps responded that he’d confer with Benson and get back to him. (Demps did not respond to multiple requests for comment.) Instead, Paul says, Demps called Davis himself—and never got back to Paul. Meanwhile, ESPN’s Adrian Wojnarowski had contacted him, Paul says, to confirm Davis’s demands.

“It was necessary to go public,” Paul says. “When I told you, ‘Here’s our intentions,’ and you say, ‘Hey, let me talk to ownership,’ and instead of you talking to ownership you call Anthony Davis? That’s called being ignored.” And trying to get between a player and his agent? “That’s a no-no,” Paul says. “Every GM knows that.”

So, in essence, Demps violated negotiation etiquette and Paul responded with the nuclear option. You can argue whether that served his client, but the episode may be the most telling measure of player power today. Because when you look at who actually suffered as a result of the trade demand—beyond a fleeting reputational dent—Davis and Paul and James barely make the list.

The Pelicans’ season soon became what coach Alvin Gentry dubbed a “dumpster fire” of speculation and recrimination; Davis’s minutes got chopped as the team waved the white flag, and on Feb. 15, Demps was fired. “I’ve never experienced anything like this in 31 years in the league. Nothing has come close,” Gentry says after a game in March. “Obviously AD is going to be fine, but there’s a lot of other guys that may not be, and that’s the sad thing. And that’s on both teams.”

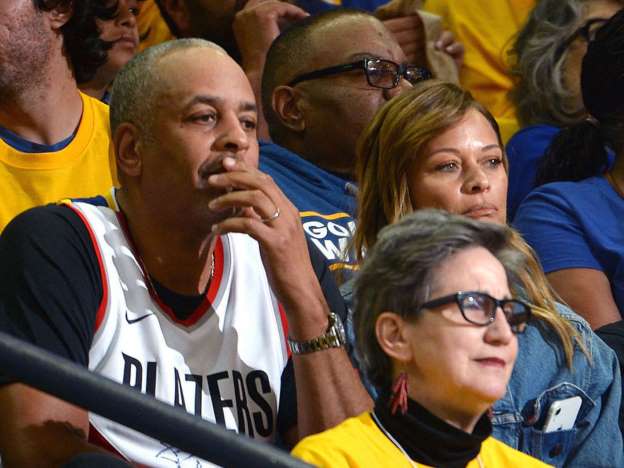

Full empowerment, so far, clearly applies to only a select few. Once the deadline passed, the Lakers’ season shuddered along as a case study in meandering dysfunction; the Christmas Day groin injury that sidelined James for 17 games didn’t help, but when the injured LeBron strolled into Staples Center on Dec. 28 toting a glass of red wine, or sat far from his teammates during losses to the Pacers and the Knicks, the message was clear.

By then, Luke Walton’s ill-fated tenure as coach had limped into lame duck territory. Magic Johnson would go on to resign as team president, bizarrely, on the last day of the season, and between that and a laughably disjointed coaching search that, on the third try, finally spit up former Magic and Pacers coach Frank Vogel, the dotty management style of previously loved owner Jeanie Buss stood revealed. And the case could be made that Paul’s maneuvering—shadowed by James—had provided the initial destabilizing push.

And yet, in the weeks after Davis’s trade bid failed, Paul signed two splashy clients: Vanderbilt’s prized lottery prospect, point guard Darius Garland, and Warriors star Draymond Green, who becomes a free agent in 2020. “I just looked at it like, ‘That’s my agent and he’s just shaking the entire league right now,’ ” Garland says. “There’s no other agent that is a household name, on every single sports show. I’ve never seen that before.”

Paul showed up as usual at Lakers home games and was in his baseline seat on March 26 when GM Rob Pelinka, fresh from talking to Buss 10 feet away, stopped by and shook hands: business as usual, for all to see.

Spin further forward and, if anything, it seems that Paul and James have grown stronger. Demps’s replacement, Griffin, is a former Cavaliers GM who has an amicable history with the duo. The Lakers? Magic’s departure sparked calls for a hard-eyed outsider to take charge; instead, Pelinka assumed Johnson’s duties, tried to hire LeBron favorite Tyronn Lue to replace Walton and, after botching that, insisted on adding James’s close friend, former Nets and Bucks coach Jason Kidd, to Vogel’s staff. By May, at least one NBA executive could be heard muttering, “Klutch Sports runs the Lakers.”

A Lakers spokesperson responded, “That’s not true,” adding, with an exasperated chuckle, “Everyone knows LaVar Ball runs the team.”

But the idea of Paul—and, by extension, James—meddling in team decisions gained further credence last month when an ESPN report on the Lakers detailed Paul voicing dissatisfaction, in November, with Walton to commissioner Adam Silver. In May, Paul also approached at least one NBA coach to gauge interest in an assistant role on Vogel’s staff, a source familiar with the conversation told SI. Last week, Paul declined comment to SI on the Silver exchange and denied broaching a role on Vogel’s staff to anyone.

“No,” Paul says. “Plenty of coaches, plenty of people have reached out to me to get guys to be an assistant. But I haven’t approached nobody about being an assistant. It’s not my place.”

The Lakers spokesperson said, “We have no knowledge” of Paul reaching out to coaching candidates and “no reason to believe it’s true.”

As for Davis, his trade saga has revealed no light between agent and client. On this late March afternoon, in fact, a knock comes at the door, and—with eerily perfect timing—in walks Davis’s girlfriend, Marlen. The conversation quickly turns to real estate. Davis is renovating a $7.5 million home out in Westlake Village, but traffic is hell, and Paul—a self-professed Redfin addict—has been sending him listings closer to downtown.

“I didn’t know you were going to be here today!” Paul says, cracking a rare grin. “Did Anthony show you the house I sent him yesterday?”

“No,” Marlen says. “I wish he did. You’ve got to send them to me.”

The two go back and forth—Marlen stressing, Paul reassuring that everything will work out. “See, what he don’t understand is, We’re trying to help him,” Paul says.

Marlen vents a bit more, Paul keeps agreeing, nodding, and she restates the problem but less urgently, as if it’s already become less of a headache. She begins edging out the door.

“He’s like, ‘The house has got to have a court and a sauna and a gym. . . .’ ”

“That’s easy,” Paul says. “That’s most of the houses, when you’re spending the kind of money you guys want to spend anyway. I got it. Trust me.”

Turning point. The standard Rich Paul story has its cinematic hinge moment: In the spring of 2002, Paul was about to board a flight to Atlanta at Akron-Canton Airport when the 17-year-old James, traveling with friends to the Final Four, spotted him wearing a vintage Warren Moon jersey. They got to talking. Plane landed, and at baggage claim Paul directed James to his supplier, the Atlanta memorabilia store Distant Replays, and told him to drop his name. A friendship struck, a career made.

The Moon jersey is the tale’s talisman: What if Paul had opted for a Fran Tarkenton? Or no jersey at all? But just as important is what happened later that night in Atlanta. A friend gained Paul entry to Sean (Puffy) Combs’s roped-off section at Club Kaya; a member of James’s posse saw him there and figured—wrongly—that he must carry serious clout in hip-hop culture.

Days later Paul was home on his couch in Cleveland when Distant Replays called to say that Paul’s new pal was in the store, buying a 1987–88 Magic Johnson authentic jersey. And in retelling the legend yet again, Paul’s eyes widen and he hits the emphasis button. “LeBron’s buying Magic’s jersey. How crazy is that?” he says. “It all comes back full circle, right?”

But something about the fairy-tale nags. “It’s all random,” Paul says. Yes, he was only 21 then. But he’d also bought his first house at 19, persuaded Distant Replays owner Andy Hyman to tutor him on the business, and at the time was making so much—up to $10,000 on a good week—selling vintage jerseys out of his car trunk that he was scouting Cleveland malls for a spot to open his own store. Hyman estimates that he’d been approached by at least 100 others, “but Rich really did stick out.”

“He was willing to put whatever it took to be a success, and convinced me that he was worth investing my time,” Hyman says. “He doesn’t take no for an answer.”

And to learn all that, Paul had to face a true turning point. That was October 1995. Rich Paul Sr.’s youngest, Little Rich, had long been a prize, studying the Robb Report behind the counter of Big Rich’s convenience store/community hub, R&J Confectionary. Glenville’s tatty corner at 12th and Edmonton had its distractions—Paul recalls dice games, men drinking, people singing, prostitution, drugs, kids playing ball in the street—but Little Rich was mostly about collecting trophies in schoolboy football and basketball.

“Small in stature, but he was big in leadership, big in knowledge,” says Ted Ginn Sr., Glenville High’s longtime football and track coach. “I used to always say, ‘Man, that’s going to be my quarterback.’ He always had that little different twist than the rest of the kids.”

But his dad didn’t want Little Rich at the local public high school. Not enough structure there, and Lord knows he needed more at home: Parents split, dad with a new wife, mom Minerva off battling substance abuse and out of his life from age 6 to 19, Little Rich living with one grandma or the other. So Rich Sr. sent him off to safer, whiter, Roman Catholic Benedictine High, with its mandatory necktie and miserable crosstown ride, just as the boy was realizing, hard, that that long-awaited growth spurt wasn’t going to come. First quarter GPA tanking, Little Rich did all he could to flunk out.

Then he walked out of Benedictine one afternoon to find his dad’s 1984 blue Coupe de Ville waiting. After they pulled away, Rich Sr. asked his son if he knew how soul singer Marvin Gaye died.

“An overdose,” Little Rich said.

“No,” he recalls his dad saying. “His father killed him, and that’s what’ll happen to you if you disrespect me the way you’ve been doing. Your grades are well beneath what your abilities are, you’re sleeping in study hall, sleeping in class, doing everything you can not to apply yourself. Those NBA dreams are out the window. You got two choices: Get your s— together and turn these grades around. Or I’m going to take you out of this world.”

Little Rich knew two things: His dad had never spoken to him like that before, and he always packed a .38 snubnose. Paul finished high school with a 3.7.

“He saw something that I couldn’t see,” Paul says. “He knew that if he allowed me to bulls— my way through this? That means that I would bulls— my way through life. He used to always tell me, ‘I’m not going to be here forever. So you have to know how to navigate.’ ”

So, yes, James and Paul became friends. It wasn’t instant. “It’s not like I met him at the airport, fly to Atlanta and I was like, ‘He’s my guy!’ ” James says. LeBron had grown up in Akron with best friends Maverick Carter and Randy Mims; Paul was the outsider. Other longtime James pals resented him. But after Paul began making trips to Akron—tapping another market for jerseys there—James asked him to come along for an AAU tournament in Chicago. When James broke his wrist, underwent surgery and ended up remaining for the summer, Paul stayed too. “The whole time,” James says.

Not quite. Paul’s girlfriend was about to deliver his first child, a girl named Reonna, and he would shuttle back and forth, so on one trip Paul had his jerseys shipped to Chicago to crack that market, too. Accompanying James to Michael Jordan’s summer workouts at Hoops The Gym, he’d sidle up to the likes of Antoine Walker or Juwan Howard and start spieling, “Yo, man, I got these jerseys. What’s happening?”

Meanwhile, with James sidelined, all they could do, really, was talk. About how Paul’s dad grew sick in ’99, ravaging Little Rich’s studies at Akron and Cleveland State, then died of intestinal cancer in 2000, leaving his son a small inheritance. About his mom, Minerva (Peaches) Martin, and how she never made one of his games growing up but now seemed clean and was trying to be part of his life again. About the ’hood and the forever pull that threatens to drag you back down.

“Criticism?” Paul says. “In my neighborhood if you had a nice car, you know what they said about it? You didn’t pay for it. If you wore your clothes a certain way, they questioned your sexuality. If you was smart in school they called you a nerd. If you had a disability, they highlighted it. There’s no praise. There’s only criticism. . . . There’s nothing on TV that could even come close to s— that I heard growing up.”

“Inner city, dad passing away, obviously mom wasn’t there all the time,” James says. “I related to that right away, you know?”

At one point, while recounting his Glenville roots on this late March afternoon, Paul calls his dad’s mother, Johnnie Mae Paul, who cared for him from 11 to 18. As the phone rings, he smiles. “You’ll hear my grandmother tell me, ‘Just put the money in the account.’ That’s all she cares about,” he says. “I’m like, ‘Grandma, who you going to pay? You’re 95. Like . . . a bill collector? Who gives a s—? What are they going to do? Dock your credit?’ ”

His uncle calls back and, on speaker, puts Little Rich’s grandmother on: She asks about his world travels and the youngest of Rich’s three kids, Zane, but not one word about money. Then she hands the phone over to his uncle, who says, “Listen, did you get my text about we need money, desperately?”

Paul’s eyes widen, as if to say, See? “Yeah,” he says. “I did.”

“O.K., we need some money real bad, now. I wouldn’t be bugging you if we didn’t.”

“O.K.,” Paul says.

Then there’s some talk about getting his uncle a ticket for a Cavs game and a reminder about calling Johnnie Mae during her 95th birthday party.

“Sunday at three o’clock,” Paul says. “That’s great. Bye-bye.”

The phone goes dead.

“The conversations that we were having were so much bigger than just basketball,” James says. “It was just life: Everything from fashion to the hustler’s mentality to family to growing up the way we grow up to music to. . . . It wasn’t just, ‘Hey, man, it was great to see what you did today in the game.’ That s— gets boring and old. The guy was teaching me s— that I thought I knew—but he had more years on me, so he was actually teaching me.

“When you’re young and grow up the way we grow up, you kind of feel like you’re by yourself—until you meet someone that is going through the same thing. . . . That’s what I mean by him teaching me, along the way. Letting me know that I’m not alone on this road.”

Is Rich Paul a good agent? On its face, this seems a dumb question to pose about someone ranked fourth, with $24.9 million in commissions, on Forbes’s 2018 list of basketball reps. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t out there in the NBA blabosphere, or that Paul doesn’t have every rant about him from Stephen A. Smith, every call for his firing by Bill Simmons, cued up on his phone as evidence of the disrespect he feels.

No one accuses Paul of writing shoddy contracts: He leaves such detail to attorney Mark Termini, focusing on the modern agent’s game—recruiting, caretaking and strategic planning. Few argue that he’s not superb at the first two, though the LeBron connection makes it hard to parse where his talent ends and James’s aura begins.

Paul and James officially went into business together—with Carter and Mims—when they formed LRMR Marketing in 2006. Paul’s decision to depart for agency work was less a break than an expansion; in 2008 he began training under Leon Rose, James’s CAA agent, and within a year landed his first first-rounder, Syracuse guard Jonny Flynn, then in quick succession Bledsoe, Tristan Thompson and Cory Joseph. NBA rules prohibited LeBron, as a player, from having a stake in Klutch when Paul opened shop in 2012—and the league has reportedly investigated Klutch to make sure there are no financial ties—but in a sense that doesn’t even matter. The perception then, as now, was that James had a proprietary interest in Rich Paul. It’s an asset Paul has never had a problem flashing.

“He is supportive,” Paul says. “And here’s my thing: When you got the hammer, you use it. I was at [CAA]. As soon as you popped in the [promotional] DVD there, he’s coming down the lane with a tomahawk—in HD! So it’s good for you? You can use it, but I can’t?

“But I don’t even put him on the phone [with a prospective client]. I could—but I don’t, out of respect for him, just in case I don’t get that person. I’ve got to keep those things in mind. And if I sign a player, that player has to be for me. Not LeBron. No. They might not even like LeBron.”

As the lone in-house voice in favor of James’s return to Cleveland in 2014—with Carter, Mims and James himself, Paul says, originally opposing the return—Paul brokered both the peace with Cavs owner Dan Gilbert and a series of one-year deals that maximized James’s value and flexibility while putting constant pressure on management to keep him happy. That pressure seemed to push Gilbert to overpay Paul clients Thompson and J.R. Smith, foreshadowing the $29.7 million the Lakers have showered on Klutch client Kentavious Caldwell-Pope over the last two seasons.

“Everyone just wants to say, ‘Oh, this guy’s LeBron’s friend and he’s used that,’” says Draymond Green. “No one talks about that extra $52 million or whatever number LeBron made by doing the deals that way. It would’ve been easy for Rich to say, ‘LeBron, I’m going to send you back to Cleveland on a four-year deal or a three-year deal with a two-year opt-out.’ No one would’ve complained. But he went a completely different route. He thought outside the box—and you see him do that with a lot of his deals.”

Even, sometimes, when it’s his own box. In October 2017, with two years left on his contract with the Suns—sound familiar?—Bledsoe publicly demanded a trade and was fined by the NBA. Two weeks later he was dealt to Milwaukee. But this past March, as if in counterpoint to the Davis imbroglio, Paul quietly negotiated Bledsoe a no-drama, happy-to-be-here, $70 million four-year extension.

“Very wise,” says an Eastern Conference executive of Paul and Bledsoe’s decision to stay put.

This month’s draft will decide whether the same can be said for the unorthodox path Paul laid for 6’9″ Darius Bazley. The Ohio five-star recruit de-committed from Syracuse in March 2018 to train on his own and—for a guaranteed $1 million, as part of a larger, incentive deal potentially worth $14 million—work three months as an intern for New Balance. “That’s extraordinary,” Garland says. “That’s crazy.” The year off may have hurt Bazley’s draft status, but as an end run to the one-and-done rule, it’s undeniably clever.

Still, Paul and James claim that it’s not Paul’s work that really irks his detractors. It’s his actual being: the combination of LeBron connection, style, youth and skin color. “Because he don’t wear a suit every day,” James says, “and he’s black.” Paul is quick to point out that he has plenty of African-American detractors in the media, and that rival agents like Bill Duffy, B.J. Armstrong and Davis’s previous rep, Thad Foucher, are African-American. The true issue, Paul says, “is not race. It’s different. I’m different. The players are different. You know why they’re different? Because they see through the bulls—. Yesterday’s players, that wasn’t the case.”

The idea that players who are on different teams shouldn’t be friendly—or even work together to achieve their aims—particularly galls. “I don’t see you saying that when CEOs go and meet up in a conference at Sun Valley, trying to figure out how to continue to run the world as billionaires,” Paul says. “But when it’s predominately black athletes, you say, ‘Oh, you all should hate.’ ”

This is why Klutch’s stable can sometimes seem like an edgy team unto itself, with players more loyal to agent, certainly, than to coach or GM or owner, posing a true threat to sports’ traditional franchise-based divisions. Other agents pitch money and stardom and, yes, the chance to control one’s own fate. But Paul seems to articulate what Green calls an “understanding and really, the priority, that he makes for players to control their own destiny—and for players to take advantage of the power that they have. That was very important for me, and something that I wanted to be a part of.”

But, James says, it’s also Paul’s personal different that “gravitates these players to him.” Teens from inner-city, single-parent households, with firsthand knowledge of violence and substance abuse, identify with Paul because his journey often parallels their own. Any agent could have facilitated James’s return to Cleveland, after all, but no one else could have pointed to the resultant 2016 championship as the capstone of an all-too-relatable family drama.

Paul’s mother, Peaches, moved back from St. Louis to Cleveland in 1999, just as his dad was fading. She was still shaky, plagued with guilt over drifting out of her three children’s lives, desperate to make up for lost time. As his career grew, Paul provided welcome and structure. He sent his mom to rehab “several times, and she went from that to having group homes,” Paul says. “I would buy the property, and she would run them to help other people stay clean.”

By the time of James’s return to Cleveland, Peaches had become a vibrant community presence, a fixture at games. Paul bought her a house and a car, paid for her vacations; they spent holidays together, and he loved seeing her chat up the ushers at Quicken Loans Arena, remembering their names. She was there in ’16 for every step in the city’s first championship in 52 years, there with 1.3 million others for the victory parade, quick to brag on her son.

“It was great to see,” Paul says. “That’s why I was at peace, because she got to do that.”

Four months later, on Oct. 22, 2016, Peaches died, at 61. He’s sure that she wasn’t using anymore. When asked the cause, Paul says, “She was just found unresponsive. I never asked.”

![]()

Early on the evening of March 31 in New Orleans, after the most charged and meaningless game of the NBA regular season, one of the league’s odder dynamic duos met on court. Both were wearing street clothes. Neither had played this day. With their teams out of the playoffs and adrift, LeBron James and Anthony Davis hugged near the Pelicans’ bench and smiled. You had to admire the audacity.

A spasm of boos filtered down from the stands. Each man covered his mouth with a hand, like paranoid football coaches fearing lip-readers. They needn’t have bothered. If the last two months had proved anything, it’s that they and their critics were speaking two completely different languages.

Among agents, front offices and league officials, Davis’s trade demand has been framed as a one-man, one-agency power grab, a threat to contract law and team chemistry, a failure—and media coverage has followed suit. But players talk of it in jarringly different terms.

That had been evident since the beginning of the month, when Davis offered his most effusive explanation of his trade demand on—of course—James’s HBO show, The Shop. “Seven years in the league, nobody’s ever said anything—no media, not a fan, not a friend—negative about AD,” James said to that episode’s assemblage. “But you can tell, the narrative changed when you don’t do what they want you to do. That’s why we’ve got to continue to control the narrative, too, and continue to back each other up, because they have so many people at the top of these food chains that will control your narrative.”

Minutes later, when asked if he’d felt a “momentum” shift, Davis said, “Yeah, and that’s what it is. All of the media coverage around me, now I’m getting a chance to take over my career and say what I want to say and do what I want to do.” He added, “So now as a player, as the CEO of my own business, I got the power.”

That, according to Green, is exactly the point. “Before AD really didn’t matter,” says the Warriors’ star, who is a minority investor in one of James’s shows, Uninterrupted. “No one was really talking about Anthony Davis in the light that a player with the status of an Anthony Davis, with his skill level, should’ve been. So he took control of his situation and said, ‘No, this is what I am and what I want.’

“He’s completely empowered. Obviously he’s still under contract for another year, but he—in a sense—now controls his own destiny. Before he didn’t. That’s very important. I don’t think it’s a miscalculation controlling your own destiny and taking control of the narrative.”

After their on-court chat in New Orleans, Davis and James separated, the boos well behind them. They returned underneath the arena to their two husks of teams, packing up the remains of a blasted season. Walton, dead coach slouching, stood against a wall and spoke to cameras about a win that no one cared about. Down the hall came Davis, staring down at his phone as he walked past. And here, perfectly timed, came James now out of the visitors’ locker room.

Neither seemed surprised. He and Davis fell into step and headed down the hall—rich, famous, untouchable. Team Klutch’s two biggest stars stopped to talk a bit more, then posed for a fan photo like tourists at a disaster scene. Finally James edged away toward the team bus. Davis was left standing alone, but soon he, too, would be gone. It is what’s next.