From Desk of the Editor

Even after 100 years, Tulsa has yet to reckon with the racism that caused the 1921 race massacre. Tulsa has one street with two names, divided by a street that, before 1921, separated white Tulsa from Tulsa’ black belt? The “black” street, heading north, is now named after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. while the “white” street, heading south, retains the name Cincinnati. Why not dedicate the entire street to Dr. King, a leader of the free world?

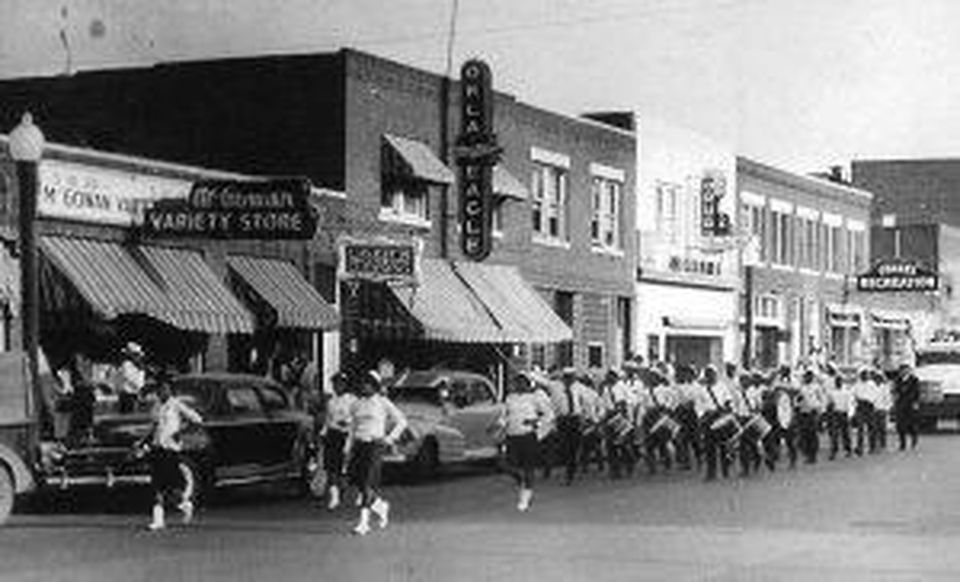

On famous Greenwood Ave., side by side, are two state universities: one historically white and the other historically black, managed by the same board of regents, when only one university should suffice. Currently, off and on, the “white” university continues to compete with the curriculum of the historically “black” university, contrary to a federal judicial mandate.

Other evidence of Tulsa’ ambivalence in dealing with racism manifests itself in perennial debates by its citizens on whether to describe the 1921 carnage as a “riot” or a “massacre” or whether to the change the name of the business district, adjacent to the Greenwood District, named after a white former Klu Klux Klan supremist, who participated in the 1921 bloodletting.

The good news is the current mayor is on a mission to unearth the bodies of hundreds of massacre victims and push for memorials to them. His actions signal that Tulsa can finally reveal the story of the good, the bad and the ugly of 1921.

Tulsa’ current mayor represents a new generation of leadership who have an opportunity to collectively turn past tragedy into a triumph of good will for the future. His efforts do not vilify but rectify attitudes of the past. His actions will lay the groundwork for the proper reconstruction of Greenwood.

The history of a reconstructed Greenwood should be told in yesteryear bricks and mortar on the outsides, and on the insides, its history told using virtual reality and interactive technologies as a way for hundreds of thousands of people to view first-hand what happened both before, during and after the massacre. The story of Greenwood cannot be told unless the histories of the Indian Removal Act, the Indian Allotment Act, and slavery are included.

The history of Greenwood must be preserved, because it is an affirmation that Black Wall is an integral part of America, a story not only of a people who suffered from the evils of racism, but a story of their resiliency.

The reconstruction of Greenwood should engender community-wide support committed to building a world class tourist attraction covering also the arts, entertainment and food. The reconstruction will not only provide business opportunities, jobs and millions of dollars within the neighborhood but be a perfect blend with other adjacent cultural sites.

The reconstruction of Greenwood will heal the ambivalence, shame and guilt some people still harbor. A reconstructed Greenwood will embrace the good of our history, while acknowledging the bad.

Tulsa is at a seminal moment in its history. Gentrification is at Greenwood’s doorstep threatening to pave over its history with bureaucratic allies spewing old concepts of “highest and best use”, not for the low and moderate income, but for the wealthy.

For more than two generations more than 100 acres of Greenwood have been possessed by higher education trust but unused with no prospects for its use by higher ed in the next two generations. It is time for that 100 acres to return to Greenwood by eminent domain as part of its reconstruction. All of Tulsa will benefit. #Greenwood #BlackWallStreet