The basketball star, radio host, and author discusses how an unfair run-in with police sparked a life of activism—and how everyone’s wrong about Michael Jordan’s legacy.

The year was 1996 and Etan Thomas, then a junior at Booker T. Washington High School in Tulsa, Oklahoma, was driving in his car on his way to a basketball game against rival Central High School when he was stopped by the police at a busy intersection. Before he knew what was happening, two and three cars had rolled up, and he was told to exit his vehicle, and produce his license and registration. Cops asked if he was in possession of any drugs or guns.

Seated on the curb, the teenaged Thomas—who, these days, after a decade-long career in the NBA, now serves as a committed social justice activist, radio host, author, and poet—watched as the police began searching the car. He was stunned and scared. He overheard one officer say he’d seen Thomas’s face before, the implication being he’d spied his mugshot. The police continued digging into every nook and cranny, working under the assumption that some form of contraband had to be present. One cop, though, remained standing just to Thomas’s left, “locked in” on him, he said, with a hand perched just above his gun holster.

For 30 to 40 minutes, he sat and stewed. Finally, the police asked for the keys to his trunk. “Don’t you need a warrant for that?” Thomas shot back. “The way they looked at me, I knew I better not say anything else.” He handed over the keys and they pulled out his gym bag with his high school logo embossed on the front. Suddenly, the officers realized why Thomas looked so familiar. “Oh, he plays basketball,” Thomas recalled one saying. “He plays for Booker T.”

So the cops trudged back to their cars, but not before one informed Thomas that he was free to go. But in the future, he should “stay out of trouble.”

“Stay out of trouble?” Thomas said. “I was so mad. I was so pissed.” His anger didn’t prevent him from playing the game, though he’d arrived late. That night, he couldn’t sleep and the following morning, he had no desire to go to school. Thomas’s mother, a teacher who prodded him to explore subjects beyond sports and encouraged his activist efforts, wouldn’t let him stay home. Sitting in class, still “steaming” with rage, and recounting what transpired the night before to a female friend, his speech teacher, Bill Bland, overheard him and brought Thomas into his office.

There, Bland told Thomas, “Listen, everything that you’re saying right now, all this that you’re feeling, put that all a speech.”

Initially, Thomas rejected the idea outright. “In a speech?” he recalled saying. “I ain’t taking on no speech. Are you serious?” But Bland, who is white, wouldn’t take no for an answer. He told Thomas that a huge chunk of the white population isn’t exposed to stories like these. Bland also reminded Thomas of his admiration for Malcolm X, who wrote and spoke with a sense of righteous indignation,

So Thomas went home that night and got to work, pouring out his emotions about still-persistent prejudices and stereotypes, his memories of being followed in the mall by rent-a-cops, and white Tulsans who took pains to avoid him on the street. He started winning speech competitions, including one held at Harvard University, to the point that the speech “went viral,” Thomas said, at a time before virality existed. Beyond the personal accolades and good press, Thomas got results.

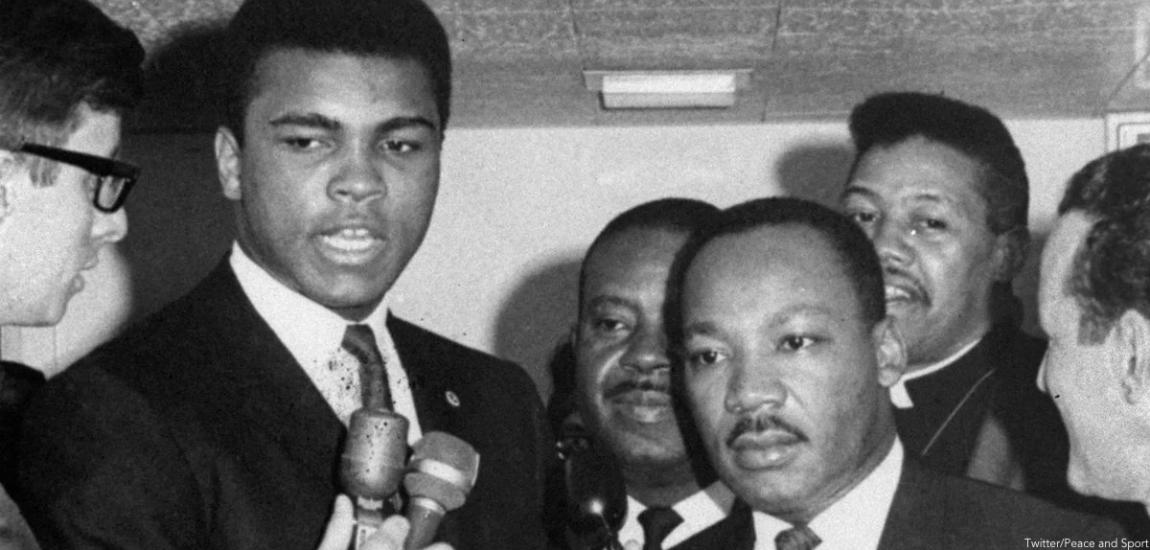

Eventually, he received a letter from the Tulsa police department informing him they had opened an internal investigation. Thomas realized that the capitulation—or even that an investigation would be opened at all—would not have occurred were he not an athlete with a platform, capable of commanding the public’s attention. From that day forward, he decided to emulate the athlete-activists he grew up worshipping, like Muhammad Ali and Bill Russell. “That’s when it all clicked,” he said.

After graduating from Syracuse University in 2000, Thomas was drafted by the Dallas Mavericks. He soon moved on to the Washington Wizards, where he immersed himself in a hotbed of political activity. During a period in history where athletes were famously apolitical, or at least remained silent, Thomas was seen as the exception to the rule. He was a frequent and outspoken critic of the Iraq War, NCAA amateurism, and the colossal failures of the Bush administration in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

Now when LeBron James calls the president a “bum,” the Golden State Warriors make it clear they have no desire to serve as a PR-friendly photo op at the White House, or members of the NBA, WNBA, and NFL take a stand against systemic racism, it’s considered the norm. Not so much during the 2000s, when Thomas was one of the few pros willing to speak out, even if the subject at hand often devolved into the meta-question of why his fellow athletes weren’t doing the same.

“What is wrong with your counterparts?” Thomas said he was frequently asked. “Where is the next Muhammad Ali and how has that been lost?”

Back then—and continuing to this day—Thomas hit the lecture and speaking circuit, often reciting poems from his 2005 collection, More Than an Athlete. In the fall of 2005, Thomas spoke at a massive anti-war demonstrationdemonstration. His then 1-year-old son Malcolm was cradled in his wife’s arms, with Dr. Cornel West scheduled to follow him. Before a an estimated 150,000 protesters, Thomas read a poem called “The Field Trip” and railed against Republican politicians:

In fact, I’d like to take some of these cats on a field trip. I want to get big yellow buses with no air conditioner and no seatbelts and round up Bill O’Reilly, Pat Buchanan, Trent Lott, Sean Hannity, Dick Cheney, Jeb Bush, Bush Jr. and Bush Sr., John Ashcroft, Giuliani, Ed Gillespie, Katherine Harris, that little bow-tied Tucker Carlson and any other right-wing conservative Republicans I can think of, and take them all on a trip to the hood. Not to do no 30-minute documentary. I mean, I want to drop them off and leave them there, let them become one with the other side of the tracks, get them four mouths to feed and no welfare, have scare tactics run through them like a laxative, criticizing them for needing assistance.

The crowd roared in approval, and once again, Thomas found himself in the center of the news cycle, even without a social media boost.

Soon afterwards, Thomas was back at practice, when he received word that then-team owner Abe Pollin needed to speak with him privately. “Uh oh,” Thomas recalled thinking. “This might be the end for me.” Instead, he walked into Pollin’s office and was met with a grin plastered across the owner’s face. His son had attended the protest and had raved about Thomas’s performance. Instead of the expected reprimand, the pair talked about political subjects like gentrification and affordable housing. To this day, Thomas wonders how that meeting might have gone down were Pollin of a different ideological bent.

Speaking of apolitical athletes, Thomas played with Michael Jordan during the last two seasons of his illustrious career. While Jordan has been retroactively pilloried for keeping his politics close to his chest—critics often cite the (very possibly apocryphal) quote “Republicans buy sneakers, too”—Thomas says the perception is inaccurate at best.

Thomas recounted a story Jordan told him about a private golf club which had an unwritten rule barring African Americans. (To the best of Thomas’s recollection, the club was located in Georgia, but he’s not sure.)

In response, Jordan purportedly approached club officials and said he’d love to play 18 holes there, but only if the policy ended immediately. Further, African Americans needed to be hired and placed in positions of responsibility such that the club could ensure that their racist practices had really changed. Sure enough, they did just that. “I wish y’all could see the stuff that he does,” Thomas said. “You’d have a different opinion of him.”

These days, in addition to penning columns for The Washington Post, HuffPost, The Nation, and ESPN, Thomas runs an educational foundation, makes frequent appearances at colleges, universities, and other symposiums and town halls, and co-hosts a weekly radio show in Washington, D.C. covering the intersection of sports and politics with Dave Zirin, the longtime columnist and reporter with The Nation.

Via text message, Zirin said: “I’ve known Etan Thomas from when he was a young player 15 years ago. His character and principles have remained remarkably and admirably consistent. Like he said to me when he was 24, ‘I’d bite my tongue, but then my mouth would bleed.’”

Thomas’s latest book, We Matter: Athletes and Activism, was published in 2018, and catalogues “this new wave of activism that had started with current athletes,” he said. The fact that this generation hasn’t shied from speaking their mind has thrilled Thomas to no end. “When this new resurgence of activism happened I was like ‘yes!’”

The book, his fourth, includes over 50 interviews and includes pretty much every outspoken figure in the world of sports: former greats like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Oscar Robertson, John Carlos, and Bill Russell; current NBA and WNBA stars Carmelo Anthony, Swin Cash, Derrick Rose, Dwyane Wade, Russell Westbrook, and Tamika Catchings; plus political figures and pundits like Chris Hayes, Dr. Harry Edwards, Bomani Jones, Jemele Hill, and more. Much to his surprise, his subjects were more than eager to speak with him. “As soon as they heard what they book was about, they tossed everything,” said Thomas. “It was like, ‘yes. What do you need?’”

For many of the interviewees, the issue that prompted them to speak out was the same, and very much the reason for the entire outpouring of activism by athletes: police brutality. Every non-indictment or refusal to press charges serves as yet another grim reminder of how persistent and pervasive the problem is, Thomas explained.

But when people, especially white people, hear that their favorite African-American athletes have all sat their children down and explained how to behave if and when they are approached by law enforcement, Thomas said, it drives home the issue in a way unlike any other. (After Trayvon Martin was killed, Thomas said he had “the talk” with his own son, age 6.)

For all African Americans, even the hint of a routine stop inevitably is a source of fear, one they live with on a daily basis. ”You pass a police car,” he said, “and your heart sinks for a second… when I get pulled over, the last thing I’m thinking about is a ticket.”

It’s a direct counter to the (sadly, still widespread) notion that African-American stars were and are somehow different, cut off from other people of color, or that their wealth served as a protective bubble. “It just resonates differently” with white people when an athlete speaks, he said, if only because, “Their son might have their jersey.”

Similarly, in We Matter, Russell Westbrook describes hearing tens of thousand of howling fans, bellowing his name and wearing an Oklahoma City Thunder jersey with his name plastered across the back. And yet, Westbrook knows that should he be pulled over with a flat tire after the game and somehow go unrecognized by law enforcement, he may be seen as a threat, no matter how many triple-doubles he racks up.

The responses to the book Thomas has received only served as further confirmation that he’s changing hearts and minds.

“We never thought it was like that for you,” Thomas said he’s been told by white readers. “We never thought that you guys were affected by this in the same way.”

Thomas stressed the importance of lawsuits filed by Thabo Sefolosha and James Blake, both of whom were jumped by the police. Since then, non-famous people of color have approached them time and time again, saying “this happens all the time” and thanking them for bringing police brutality to the forefront, because “we’re voiceless. Nobody listens to us.” On the other hand, “[people will] listen to Thabo Sefolosha. They’ll listen to James Blake. They’ll listen to Michael Bennett,” Thomas said.

In addition to the bold-font names in his book, Thomas made sure to interview family members of Terence Crutcher, Philando Castille, Eric Garner, Trayvon Martin, and other victims of police violence. He’ll routinely bring them along with on public speaking engagements because, “I want them to tell their story,” Thomas said. “I don’t want the story to die down, just because the story’s not in the headlines any more.”

He continued: They’re continuously fighting, so for me to be able to use my platform to assist them… it’s overwhelming that I’m able to do it.”