By Jamilah Pitts

It is easy to celebrate black women when it is convenient or comfortable. Americans appreciate black women when our voter turnout leads to necessary victories in Congress. We loved Beyoncé, until she said to stop killing us, and we love Oprah, so long as her messages do not become too radical, of course. But rarely does American society acknowledge the contributions of black women or their role in our history.

There is a great danger in overlooking the roles black women have played in movements of resistance, resilience and revolution. It is important that we break the cycle of this singular form of storytelling.

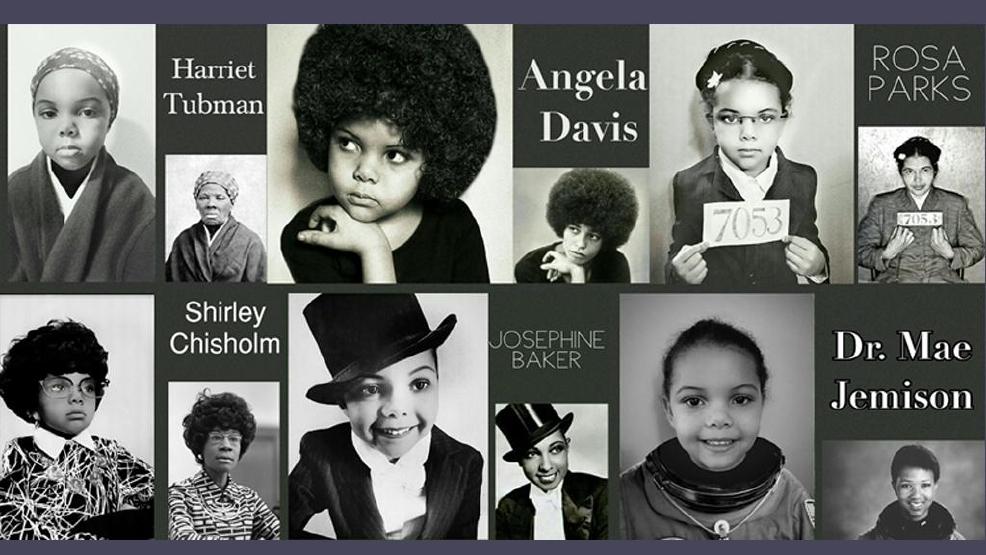

So, this Women’s History Month, instead of another lesson around mainstream feminist movements, most of which excluded black women, I hope that my fellow educators will pause to focus on all that black women, and other women of color, have contributed to this country and this world. Moreover, let’s talk about more than just Rosa Parks and Harriet Tubman ― especially in the narrow ways that we often learn about them.

The earlier that we expose our children and students to the power, reach and depth of black women, the less likely they may be to accept stereotypes and popular images that reduce black women to angry, hypersexual or superhumanly “strong” beings. Black girls need to know they are more than the “mules of the world” who simply deal with all that is pressed upon them.

One such way to include the voices of black women is to begin with one of the major faults in how the civil rights movement is taught. Many teachings focus solely on the contributions of men, save Parks (we will get to that in a moment), and fail to highlight the roles that black women played in the movement. Even Malcolm X acknowledged during his time that the most disrespected and unprotected person in America is the black woman.

Without giving proper mention to women like civil rights activist Diane Nash and political leaders Shirley Chisholm and Fannie Lou Hamer, girls and boys alike begin to rely on false narratives that suggest that black women either played subservient roles in movements for liberation and resistance, or that we were absent altogether. Moreover, when black women are hushed in historical texts, it allows men and white people to continue to ignore us.

The works of Alice Walker and the Combahee River Collective help us understand the ways in which black women’s voices have often been excluded from historical movements. Walker, a writer and activist best known for her novel The Color Purple, coined the term “womanist” in In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose. A “womanist,” Walker defines, is “a black feminist” or “feminist of color.” In creating this term, Walker sought to include the perspectives of black women and women of color within feminist thought and the feminist literary canon.

The Combahee River Collective Statement of 1974, a statement written and organized by black lesbian women who met regularly to discuss and act upon black feminist politics, addressed the ways in which the feminist movements sought only to serve white women, thereby ignoring the demands and interests of black women who were also suffering.

Students and staff should be exposed to the works of Anna Julia Cooper, an educator and one of the first African-American women to earn a doctoral degree; of poet, writer and activist Audre Lorde; of Angela Davis, a political activist, scholar, and writer whose work and activism focuses on oppression, race, gender inequality and mass incarceration; of Sojourner Truth and Ida B. Wells, both advocates for women’s and civil rights.

Students deserve to hear about the experiences of marginalized groups of people, particularly the experiences of black women, through the works of Ntozake Shange, Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Zora Neale Hurston, Warsan Shire and Nayyirah Waheed.

Incorporating black women’s stories and voices into our classrooms and curricula is powerful, healing and revolutionary. Students should grapple with the intersections at which black women, particularly black, gay and poor women, live, as this paints a clearer picture of the atrocities that this great nation has inflicted upon its most vulnerable citizens.

Diving into this type of content may give some educators pause, particularly those who feel that the messages created by these women are too “radical,” or that sexual orientation and gender nonconformity are too nuanced and political conversations for the classroom. However, because teachers have the privilege of being able to influence countless minds on a daily basis, it is important that we use our skills and tools to address this very challenging work.

If sexism, racism, and homophobia are mindsets that are taught, it is increasingly important that we teach students to think critically, to examine their worlds and beliefs, and to be compassionate, empathetic change agents. We only further perpetuate the oppression if we fail to speak on issues that matter.

Focusing on the stories of black women opens the door for nearly every form of injustice and oppression to be explored.

Educators also have to do a better job at dismantling the myths about Rosa Parks that reinforce the idea that black women are only powerful and worthy of remembrance when they are perceived as gentle and “respectable.” Texts such as Danielle McGuire’s At the Dark End of the Street debunk the narrative of a docile Parks who was too physically “tired” to give up her seat; she was, in fact, an experienced civil rights leader who was mentally tired of always having to “give” in to white supremacy.

McGuire’s book also looks at the politics of respectability prevalent during the civil rights movement (and even still today). Claudette Colvin, an activist in Alabama, was arrested months before Parks for refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger. The NAACP chose not to use Colvin’s arrest in the case against segregation laws in Alabama because she later became pregnant and was unmarried.

Perhaps the reason that black women’s experiences are often left out of dominant historical narratives is because their plight underscores the harsh realities of both patriarchy and racism, two forms of oppression that have existed since the country’s founding. Further, acknowledging the contributions of black women would shift some power away from straight white men, who have always dictated and dominated historical narratives.

For teachers who seek to use their classroom as a place for truth-telling and to do social justice and human rights work, focusing on the stories of black women opens the door for nearly every form of injustice and oppression to be explored.

As educators, it is important that we commit to doing this work. It is time for black women to be received as more than angry figures or passive spectators, particularly without examining past and existing modes of oppression, violence and silencing. This history has created the resilient, relentless, no-nonsense women you dare to call “angry.”

Jamilah Pitts is a writer and teacher in the New York City neighborhood of Harlem. She is an alumna of Spelman College and is pursuing further graduate study at Teachers College of Columbia University.