By Morgan Phillips

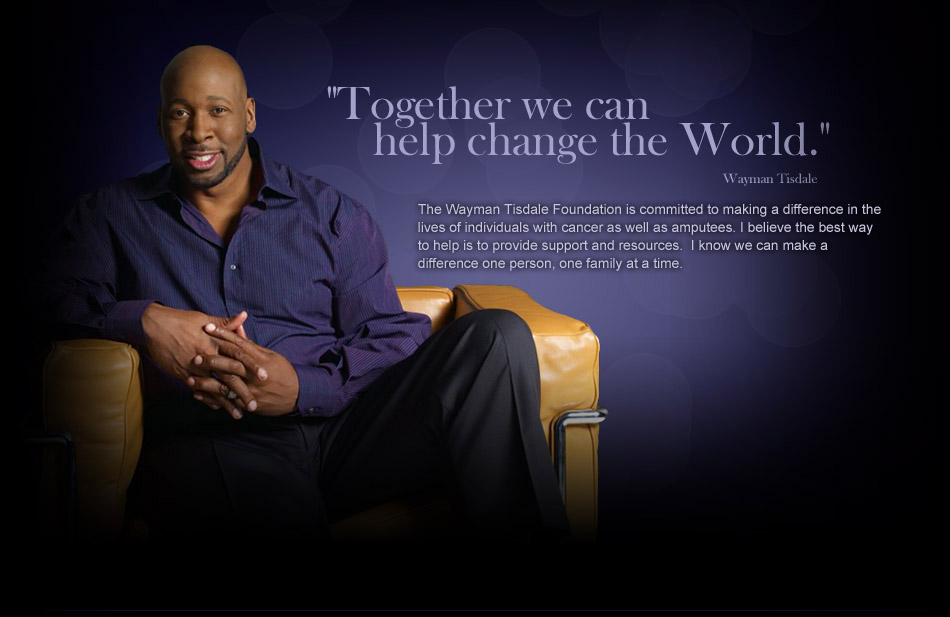

The Wayman Tisdale Foundation is a local nonprofit that provides eligible individuals, like Eden, with unmet prosthetic needs.

The Huff family receives a devastating prenatal diagnosis

Merton Huff Jr. is both a pianist and a barber. His hands are his livelihood.

So he was more than devastated when he and his wife, Monique, found out during an ultrasound that their first child, a girl, would be born with no left arm.

They recall their initial disbelief as a tech measured and re-measured the baby’s limbs at 20 weeks gestation. They drove home from the doctor’s office in silence.

As reality sank in, the couple politely smiled through their own gender reveal party thrown by family and friends. “We weren’t ready to tell everyone yet (about the birth defect),” Merton says, “so we had to carry it.”

Over the next several months, the couple shared the news with those closest to them, including members of their church, Metropolitan Baptist, where Merton is the worship leader.

Merton says thinking about his unborn child’s condition initially made him angry. “I was asking God, ‘Why me?’ Everything I do, I do with my hands,” he says. “Everything you can think of, we thought.”

He recalls thinking about his daughter’s future and then attempting himself to do everyday tasks, like taking a shower or tying his shoes, with one hand behind his back.

With the encouragement of family, friends and even strangers through Facebook support groups, the Huffs eventually found strength through prayer and Scripture.

“God never promises us everything is going to go our way,” Merton says, “but we’ve been able to see God in the process.”

The late Tulsan Wayman Tisdale’s foundation offers hope

Before their daughter’s birth, a friend at church told the Huffs about the locally based Wayman Tisdale Foundation, which identifies eligible individuals with unmet prosthetic needs and pays for cutting-edge prosthetic care.

The late Tulsan Wayman Tisdale, a Booker T. Washington, University of Oklahoma and professional basketball player and jazz musician, received a prosthetic leg after an amputation due to bone cancer. He created the foundation with his wife, Regina, before his death in 2009 at age 44 from complications of his radiation treatment.

Over the past eight years, the Tisdale Foundation has funded $47,500 in prosthetics for eight individuals across the state. The Oklahoma City-based Scott Sabolich Prosthetics and Research, which created a series of prosthetic legs for 6 foot, 9 inch Wayman — some of the tallest it has made — has created most of the devices for the foundation’s grantees.

Over the past eight years, the Tisdale Foundation has funded $47,500 in prosthetics for eight individuals across the state. The Oklahoma City-based Scott Sabolich Prosthetics and Research, which created a series of prosthetic legs for 6 foot, 9 inch Wayman — some of the tallest it has made — has created most of the devices for the foundation’s grantees.

Regina says the Tisdale Foundation started out providing scholarship money to students in Tulsa schools who were athletes and musicians like Wayman. But his amputation experience — and learning that prosthetic limbs can cost between $5,000 and $50,000 — caused him to shift the foundation’s mission.

“We were sitting in the hospital one day, and he said, ‘I want to change the foundation,’” Regina recalls. “I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ He said, ‘I want to give prosthetic devices to Oklahomans in need.’

“It’s just so Wayman,” she says. “It was just his heart to help individuals.”

Over the past eight years, the Tisdale Foundation has funded $47,500 in prosthetics for eight individuals across the state. The Oklahoma City-based Scott Sabolich Prosthetics and Research, which created a series of prosthetic legs for 6 foot, 9 inch Wayman — some of the tallest it has made — has created most of the devices for the foundation’s grantees.

“Wayman and Regina were fantastic to work with, and they’re very inspiring people,” says prosthetist Scott Sabolich, whose company donated the time and labor to create grantees’ prosthetics, while the foundation paid for materials.

“Wayman had health insurance and was able to cover a copay and deductible, but he realized that not everyone can do that,” Sabolich says. “Many people don’t even have health insurance.”

For those who receive one, an artificial limb can be life-changing. Regina recounts a single mother of three who went back to school after receiving her prosthesis. A 25-year-old man who lost his leg in a farming accident went back to work and got married after receiving his device.

These heartwarming stories are what keep Regina going. “Our mission is being fulfilled in the sense that these people are able to get on with their lives,” she says.

In April, the Tisdale Foundation helped an individual whose life was just beginning. It granted its first prosthetic for a child, Eden Huff.

Eden takes baby steps

Eden, whose left arm stops just above her elbow, also was born with hip dysplasia on her left side. To help correct her hip condition, she was in a harness for her first three months. Eden was only out of the harness for bath time, Merton says. “It was really difficult.”

At 9 months old, the Tisdale Foundation facilitated the fitting of her first prosthetic arm. The immovable device, called a passive prosthetic, is mostly for balance and secures with a strap across her body. If Eden wears it under long sleeves, one can hardly tell the arm isn’t real when she is sitting up.

Since children grow quickly, they require new prosthetics every few years. The foundation will fund one more device for Eden, likely around age 2, Merton says.

At 14 months old, Eden underwent hip surgery to add a metal plate to support her hip socket. As a result, she was in a cast for three months. As she grows, she will have to have other hip surgeries, just as she will have to have new prosthetics.

For now, therapists come to the Huffs’ home once a week for physical therapy, which involves helping Eden stand. She wears her prosthetic arm while standing between a set of parallel bars about 2 feet high. “She can take a few steps, but doctors don’t want us to rush her walking so she can build strength,” Merton says.

Coincidentally, before Eden’s diagnosis, Merton was already familiar with the Tisdale Foundation — as an entertainer. For the past four years, he’d been to hired provide music at its Jazzy Strokes fundraiser golf tournament, held each August.

Now he understands the foundation’s impact at a level few can.

“We’re so thankful for the Tisdales,” Monique adds. “I really don’t know if (Wayman) even thought about the extent to which he would impact people in the future.”

Wayman’s legacy lives on

Together the Tisdales had three daughters and a son. Only one of their six grandchildren, Bailey, met their Papa.

“Through cancer, through the amputation, he was still the guy I started dating at 16,” Regina says of Wayman, nine years after his death. She is speaking from the community room of the Wayman Tisdale Specialty Health Clinic, 591 E. 36th St N., which opened in 2015. This past June, Chouteau Elementary, also in north Tulsa, was renamed the Wayman Tisdale Fine Arts Academy.

Regina is clearly proud the community has helped keep her husband’s legacy alive.

Regina Tisdale founded the Wayman Tisdale Foundation with her late husband, Wayman Tisdale, inset. Along with addressing and providing prosthetic care to eligible individuals, the foundation recently launched the Wayman’s Way initiative, which promotes positive lifestyles and preventative health care with an emphasis on health and wellness, childhood health education and nutrition awareness.

Regina Tisdale founded the Wayman Tisdale Foundation with her late husband, Wayman Tisdale, inset. Along with addressing and providing prosthetic care to eligible individuals, the foundation recently launched the Wayman’s Way initiative, which promotes positive lifestyles and preventative health care with an emphasis on health and wellness, childhood health education and nutrition awareness.

Never a fan of public speaking, she says leading the foundation has been a challenge for her. “When we first got married, you couldn’t get two words out of my mouth,” she says. “Wayman pulled that out of me. When he passed away, I didn’t have a choice.”

Fundraising has been especially tough, Regina says, because she hates asking people for money. Now the foundation has staff who handle much of the development. “After he died, I literally wrote this in my journal: ‘Wayman, this is above my paygrade,’” Regina recalls. “‘It’s your fault because you gave me a life where I didn’t have to ask for anything.’”

Knowing the Tisdale Foundation will provide Eden with one more prosthesis removes some of the family’s financial burden, say the Huffs.

They say they will fund future prosthetics — if Eden wants to continue wearing them — with the help of insurance and through personal savings.

Overall, Monique says they are taking things “one day at a time” and focusing on showing Eden that she is special and important. It’s something they will also teach their second child, a son named Judah, who was born in July.

Of her daughter, Monique says, “We realized we can’t reduce her life to one missing arm because she would never experience all that she should.”

For more information on the Wayman Tisdale Foundation, visit waymantisdale.org.